![]()

PART ONE

![]()

I

THE GUCCI MAN

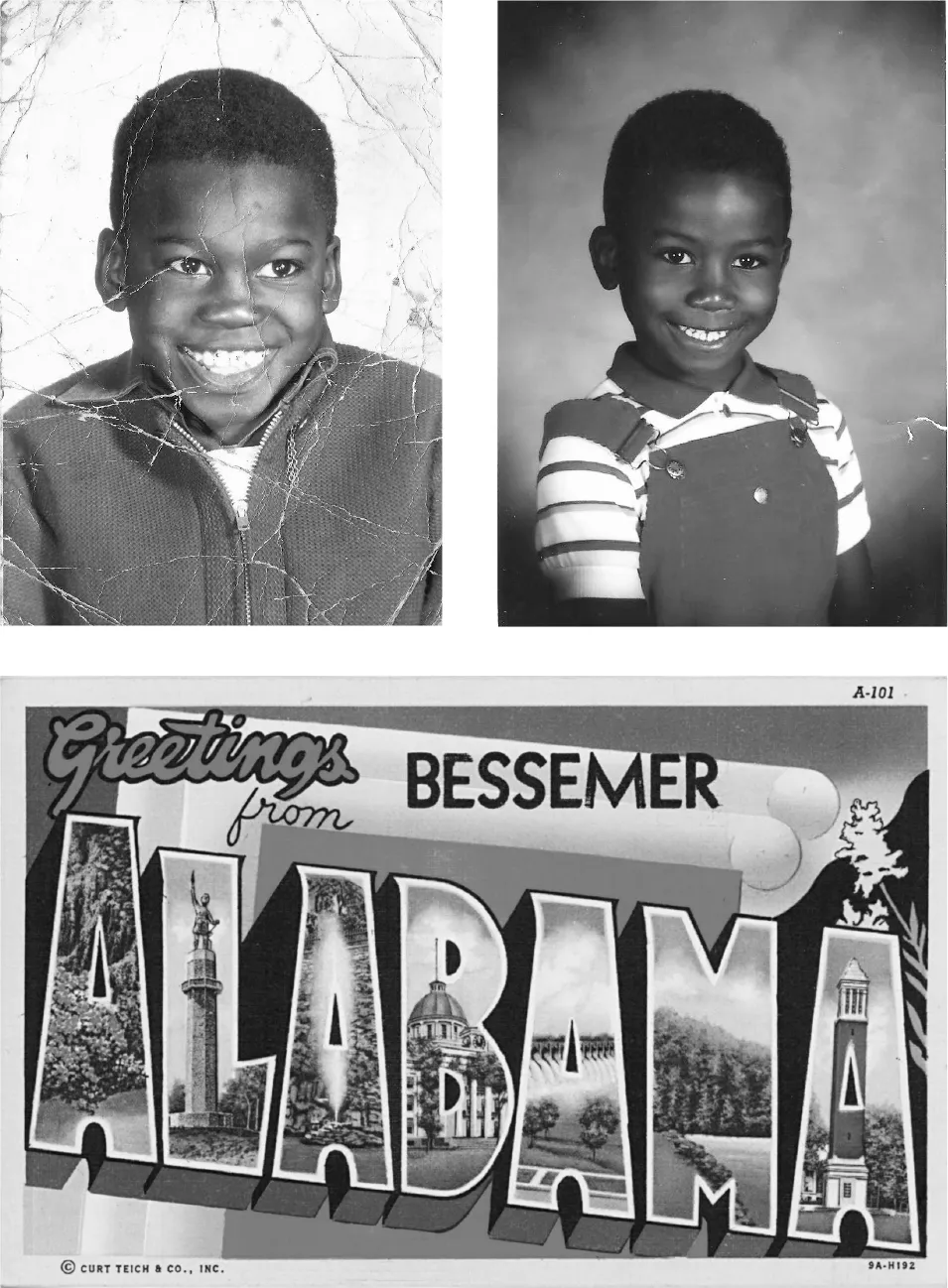

I’ve got such strong ties to the city of Atlanta that people forget I didn’t move to Georgia until I was nine.

My roots are in Bessemer, Alabama, a country coal town about twenty miles south of Birmingham. My great-grandparents on my daddy’s side, George Dudley Sr. and Amanda Lee Parker, moved there in 1915 from the even more rural Greensboro, Alabama, where the Dudley family tree dates back to the 1850s.

George Sr. and Amanda headed to Bessemer in search of a better life. It was an area rich with natural resources—coal, limestone, ore—all the ingredients to sustain what was then a booming industry—steel. George Sr. managed to secure employment as an ore miner at the old Muscoda Red Ore Mining Company, near the community of Muscoda Village.

Back then steel companies looked out for their workers. Employees received cheap housing so most of the black miners of the mining community lived in company-owned homes. They created schools, a church, a medical dispensary, and a commissary where workers could purchase food and supplies on credit.

Soon enough white folk of the area turned jealous of the blacks’ housing and the company-operated social programs, and decided they wanted them for themselves. So the blacks were moved out. Many were left homeless. But that wasn’t the case for my great-grandfather. With the help of his money-minded wife he purchased a small home at 723 Hyde Avenue in Bessemer, a property that is family owned to this day.

George and Amanda had twelve children together—and 723 Hyde was bustlin’. Their household was a place where family and friends in need of a hot meal or a place to stay were always welcome. They were loving folks with big hearts.

When George Sr. would collect his paycheck, the stub would often be blank because of the money he owed the commissary for food. It never bothered him in the slightest.

George Sr. loved food—all the Dudleys did—and he loved to see his family eating right. He’d come home exhausted after a long day’s work at the coal mine and still find the energy to cook something up for his family. And he’d always bring back a treat for his children—cookies, penny candy, fruits. He’d divide equally among all of ’em.

One of those twelve children was my grandfather James Dudley Sr., born April 5, 1920. James Sr. spent twelve years in the military as a cook and fought in the Second World War. After his time in the service he taught radio and television at Wenonah Technical School and later on worked as a postman.

James Sr. married Olivia Freeman on September 20, 1941. They had eleven children, the sixth of whom was my father, Ralph Everett Dudley, born August 23, 1955.

Throughout the course of his life my father went by a lot of aliases. Slim Daddy. Ralph Witherspoon. Ricardo Love. For the purposes of this story, a nickname he received as a young boy matters most: Gucci Mane. That’s right. He’s the OG.

See, James Sr. had always fancied himself a dresser. He loved him some nice clothes and expensive leather shoes. He’d spent time in Italy during his years in the service, which is where he fell in love with the Gucci brand.

Originally he’d given the nickname Gucci to one of his nephews, an older cousin of my father’s whom my father used to follow around all the time. Annoyed by his younger cousin always begging to hang and telling him “Come on, man,” he started calling my father the “Gucci Man.” As for how “man” became “Mane,” well, I’m pretty sure that’s just some country, Alabama twang. I’ve got an uncle on my momma’s side they call Big Mane.

My auntie Kaye told me that as a boy my father was sharp, soft-spoken, and sensitive. He was always at the top of his class. He suffered from a speech impediment and would have to spell out words he was trying to say so people could understand him. James Sr., a military man, didn’t always approve of his son’s mild-mannered temperament, and would yell at him for refusing to fight with the boys in the neighborhood.

But as a young man my father came into his own. With his speech impediment gone he became a slick talker, very much a people person. He wore Levi’s and played the guitar and listened to Jimi Hendrix, Peter Frampton, Mick Jagger—all the rock ’n’ roll stars of the sixties and seventies. His bedroom had guitars mounted on the walls and tapestries hanging from the ceiling. He drove a two-seater drop-top convertible, an MG Midget. He was supercool, ahead of his time for a young black man from Alabama.

After graduating from Jess Lanier High School in 1973, my father enlisted in the US Army, spending two years stationed in South Korea. When he returned to Alabama in 1976, he briefly attended college before getting a job making dynamite at the Hercules Powder plant in Bessemer. After that he worked at the Cargill chemical plant. My father took full advantage of the GI Bill and had quite a bit of technical schooling under his belt. The guy was smart as hell.

But I never knew my father as a working man. I never saw him hold a nine-to-five job my whole life. All of that happened before me. I understood my father as a hustler, an alley cat, someone who more than any other person I’ve met was shaped by the streets. But I’m getting ahead of myself. More on all that later.

My momma’s from Bessemer too. Vicky Jean Davis is the daughter of Walter Lee Davis. Walter and his siblings were raised not too far from Montgomery, Alabama, in Autauga County.

Walter was stationed in the Pacific during World War II, where he served aboard “Old Nameless,” the battleship officially known as the USS South Dakota. He was a cook on Old Nameless, but when the Battle of Santa Cruz went down in October 1942, he hopped on one of the antiaircraft machine guns and got it poppin’. He took down a few planes before he got chewed up by one of the Japanese strafers. He got shot up so bad it made it into the papers.

“He looked like one of his own kitchen colanders,” said the captain, Vice Admiral Tom Gatch. “But they couldn’t kill him.” It was a miracle he survived that battle.

When he came home Walter relocated to Bessemer, where he found employment at Zeigler’s, a meat packaging company not unlike Oscar Mayer. He was one of their first black supervisors.

He also met his wife, Bettie. Together they had seven children—Jean, Jacqueline, Ricky, Patricia, Walter Jr., Debra, and Vicky. Bettie had two sons—Henry and Ronnie—from two prior marriages.

My momma’s upbringing wasn’t easy. Around the time of her birth Walter and Bettie took up drinking. Soon enough, violence became an everyday occurrence in the Davis household. To this day my family tells the craziest stories about my grandmomma. Bettie Davis was a mean drunk like you wouldn’t believe. This little lady would get to fighting with somebody at dinner and reach across the dining room table and stab them with a fork. Hell, I heard she shot my granddaddy once.

When she passed away from a stroke at the young age of forty-four, my mother’s sisters had to take on the role of caretaker for their younger siblings. They kept a roof over everyone’s head and food on the table, but there was a lot to be desired. My aunties were only a few years older than my momma and they hadn’t had the best role models themselves.

But as resilient people do, my momma adapted to survive. Vicky Davis always was, and to this day remains, a very smart, hardworking, resourceful woman. And tough. She graduated from Jess Lanier High School in 1975 and went on to get an associate’s degree at Lawson State. After Lawson she enrolled in Miles College, a historically black school in Fairfield, Alabama, where she studied to become a social worker.

That’s around the time she met Ralph Dudley, in 1978. My father already knew the Davis family. He’d been classmates with my aunt Pat at Lanier. But he’d never met my momma. When he did it was instant attraction. They fell in love quick.

My momma already had a son, my older brother, Victor. He goes by Duke. But Duke’s father wasn’t in the picture. Duke’s got another half brother, Carlos, who was born the same month and year he was. So that’s what his daddy was up to then.

During my momma’s pregnancy my father got into trouble with the law. He’d been arrested for having drugs on him—no small crime in the seventies—and was facing time. James Sr. had recently passed away unexpectedly and my grandmother Olivia—whom we call Madear—still had kids to raise. So instead of facing the music, which would cause Madear the undue stress of seeing her son sent to prison, my father fled.

He headed north to Detroit, which was where he was on the day of my birth, February 12, 1980.

Because my father wasn’t around to sign the birth certificate I was born Radric Delantic Davis, taking my mother’s last name. Like my conception nine months before, my first name, Radric, was a product of my parents’ union—half Ralph, half Vicky.

![]()

II

1017

I came up in my granddaddy’s house at 1017 First Avenue—an olive-green, two-bedroom in Bessemer near the train tracks. Inside were my granddaddy, my momma, Duke, and me. But it was never just us.

1017 had a rotating cast of family characters who could be staying there at any time. Walter Jr., my uncle—we call him Goat—was always in and out of jail. When he wasn’t locked up, he’d be there. Or one of my many aunties and her kids might move in for a while.

The house was small, 672 square feet to be precise, so things got tight. Sometimes Duke and I got the bunk beds. Sometimes I’d be on the couch. Other times the floor. My granddaddy had an extra roll-away bed in his room. At one point there was a bed in the living room. It switched up.

Growing up, I called Walter Sr. Daddy. He and I were close. Tall and slender, my granddaddy appeared every bit the gentleman. He wore a suit and tie every day. On Saturdays one of my cousins would go to the cleaners and pick up his freshly pressed clothes for the week. They’d grab him cigarettes too. This was back when kids could buy cigarettes. Camel Straights.

My granddaddy and I had this thing where I would see him up the block coming home from the First Baptist church. As soon as I’d see him turn the corner I’d stop playing kickball or football or whatever it was I was doing and race up First Avenue to meet him. I’d grab his hand and help him walk the rest of the way home.

“Your grandson sure loves you, Mr. Walter,” the old ladies would call out from their porches.

The funny thing was my granddaddy didn’t need help walking. His cane had gotten himself to church just fine. But he played along, putting on a limp like he needed my help. That was our inside thing and I felt proud to walk alongside him.

Like many in my family, he had his demons. I don’t know if my granddaddy turned to the bottle to cope with the mental or physical effects of war. Deep scars crossed his body. Or maybe it was something invisible. Whatever it was, the man was a drinker.

In Bessemer most folks drank the wino wines—Wild Irish Rose, Thunderbird—but my granddaddy liked liquor. Bourbon. He had a girlfriend, Miss Louise, and the two of them would get pissy drunk at one of the shot houses nearby until they were stumbling down the street with bloodshot eyes.

But I loved my granddaddy. Every night I would sit on his knee and we’d watch TV. When I would act up he’d chase me around the house, saying he was gon’ whip me, and I’d dive under his bed laughing, knowing that he couldn’t catch me down there.

I was just as close with Madear, my grandmother on my father’s side. She’d played a big part in my childcare while my momma was in college working toward her degree.

Madear’s house was over in Jonesboro Heights, an even quieter, even more country part of Bessemer that sits on a hill outside the city limits. It’s a tight-knit community made up of three streets—Second Street, Third Street, and Main Street—with two churches: New Salem Baptist and First Baptist. It’s known fondly by its residents as the Happy Hollow.

As soon as I learned to ride a bicycle I struck out on my own to go there. I’d get in trouble for doing that. It wasn’t like the Hollow was around the corner. It was a ways away. You had to cross the main highway to get there. For a little boy, the mile-and-a-half trek was a real journey. But I loved spending time with Madear. She spoiled me.

Whenever I’d come over she’d have something for me—toys, coloring books, GI Joes. We’d watch TV for hours. Sometimes wrestling, sometimes Wheel of Fortune, sometimes Jeopardy!

“There’s my smart grandbaby,” she’d say if I knew the answer to one of the trivia questions. “I don’t even have to think anymore because I know Radric knows the answers.”

If I wasn’t with one of my grandparents, then I was following my brother around. Duke is six years older, so you know how that goes. To me he was supercool, and I was his shadow. I really got on his nerves. I would always be stealing his clothes to wear and trying to hang with him and his buddies.

Duke didn’t care for that much, but I didn’t care that he minded. I’d trail him and his little crew on my bike, usually from a distance because my brother would beat my ass if he knew I was following them. He didn’t want me to see what he and his friends were up to. I’d watch them steal beers from the corner store or throw rocks through car windows and take off running. It wasn’t much. Country teenagers getting into country teenage shit. But I was a curious child. I needed to know what everyone was up to.

Duke was a bona fide music enthusiast. He put me onto all the great hip-hop of the eighties. Every week he would go to the Bessemer Flea Market and come home with whatever new album had just come out. He’d pop the casse...