eBook - ePub

Little Book of Restorative Justice for Colleges and Universities

Repairing Harm And Rebuilding Trust In Response To Student Misconduct

David R. Karp

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 92 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Little Book of Restorative Justice for Colleges and Universities

Repairing Harm And Rebuilding Trust In Response To Student Misconduct

David R. Karp

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Here's a call to colleges and universities to consider implementing restorative practices on their campuses, ensuring fair treatment of students and staff, while minimizing institutional liability, protecting the campus community, and boosting morale. From an Associate Dean of Student Affairs who has put these models to work on his campus.

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Little Book of Restorative Justice for Colleges and Universities un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Little Book of Restorative Justice for Colleges and Universities de David R. Karp en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Law y Alternative Dispute Resolution. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

LawCategoría

Alternative Dispute Resolution1.

Introduction: The Story of Spirit Horse

Horse rustling is not the kind of trouble typically caused by college students. But Skidmore College is located in Saratoga Springs, a small city in upstate New York that is known for its high-society thoroughbred racetrack. The population triples in the summertime, and the downtown streets become as bustling and lively as Greenwich Village.

A few years ago, the Saratoga County Arts Council launched a project that decorated the town with life-size fiberglass horses painted by local artists. One of the more interesting horses, called Spirit Horse, appeared to be passing through the large plate-glass window of an antique shop. The statue, cut in half, stood regally on the sidewalk with its rear end inside the store on the other side of the glass. The horse had two glowing green eyes that lit up at night, adding to the spectral mystique.1

Late one night, a Skidmore student was returning from the nearby bars and decided he wanted Spirit Horse for his very own. He was able to wrench the front half from its pedestal on the main thoroughfare and was also easily observed by a taxi driver and other witnesses. Police arrived while he was still sweaty and out of breath from hauling it to his second story walk up.

Restorative justice is a collaborative decision-making process that includes victims, offenders, and others who are seeking to hold offenders accountable by having them (a) accept and acknowledge responsibility for their offenses, (b) to the best of their ability, repair the harm they caused to victims and communities, and (c) work to reduce the risk of reoffense by building positive social ties to the community.

Though this was a minor incident along the continuum of crimes, college administrators were not pleased to read the front page headline, “Skidmore student is charged in theft of decorative horse.” They were rightly concerned this would reinforce a community perception of our students as selfish, over-privileged, and a nuisance.

As a restorative facilitator for this case, I was able to host a restorative justice dialogue with the key stakeholders including the student, the artist, the antique shop owner who had paid for the horse, and the arts council director. As is typical of our process, we worked through the case as a campus disciplinary matter before it was handled in the criminal court. There he had been charged with third degree grand larceny and possession of burglary tools—a wrench and pliers.

The beginning of a conference includes storytelling by the offender and each of the harmed parties. The arts council director was surprised to learn, for example, that the student had worked for his hometown’s arts council the summer before. With a mixture of remorse and embarrassment, the student revealed that one of his motives in taking the horse was his appreciation for the project and his desire to have a souvenir from it. He quickly added his recognition that this was not the best way to support the arts.

When the restorative justice participants heard from the artist, it was the student’s turn to be surprised. The artist described how he had been alerted quite early in the morning after the crime and quickly went downtown to inspect the damage. Of course, he said, he was upset about the theft and damage to his artwork. However, what really upset him were the two live wires that had been ripped from the glowing eyes and left exposed on the sidewalk. He wondered aloud what would have happened had he not been there to remove them. Soon the street would have been filled with toddlers and dogwalkers. Had the student considered that, he asked.

The storytelling in a restorative justice process is designed to explore the harm caused by an offense. In this case, there was property damage and loss but also the risk created by the electrical wires, the communitywide disappointment and anger about vandalism to a public art display, and a spoiling of the reputation of the college.

Once harms are listed, the group works toward solutions that can repair the damage and restore community trust. An agreement was reached in this conference that met everyone’s concerns. The student was to be responsible for:

Impressed by the agreement reached at Skidmore, the Saratoga district attorney negotiated a sentence called “Adjournment in Contemplation of Dismissal.” This meant that the student would admit guilt, but as long as he complied with the restorative agreement and stayed out of trouble for six months, his conviction would be sealed, and he would have no permanent criminal record.

About this book

When I facilitated the Spirit Horse case, I was an assistant professor just learning about restorative justice (RJ) and how it was being applied in criminal justice cases around the world. We decided to apply restorative justice principles in this case and discovered the benefits for the student, the harmed parties, and the wider community. Personally, I learned the value of putting an academic interest to the test in a real-world case.

Nearly ten years later, I have continued to examine the use of restorative justice on the college campus through research, teaching, facilitator training and practice, and program implementation. As a student affairs administrator, I have become deeply committed to the concept and practice of restorative justice. I have experienced how it can work given the very real pressures among campus conduct administrators to manage high case loads, ensure fair treatment, minimize institutional liability, protect the campus community, boost morale in a division with high turnover, and help students learn from their mistakes without creating insurmountable obstacles to their future successes.

I wrote this book to encourage colleges and universities to seriously consider implementing restorative practices on their campuses. It is designed to provide an overview of RJ principles and practices, evidence of its effectiveness, and tips on implementation. I provide case examples from a variety of campuses already using RJ, from large public universities to small, private liberal arts colleges.

Having conducted numerous campus RJ trainings, I have seen the need for a short, accessible guide to the topic that can be used as a training manual or stand alone as an introduction for campus decision-makers. Faculty who teach restorative justice may use this as a supplemental text that engages students in a topic of great concern to them—how they may be treated if they get in trouble.

Currently, many people question the value of higher education arguing that it is too expensive, that students are not learning well, and that they are improperly trained to enter the workforce. In the race to cut costs and expand vocational training, institutions often forget to nurture the campus community. The Native American restorative justice practitioner, Ada Pecos Melton, reminds us that “restorative principles refer to the mending process for renewal of damaged personal and communal relationships.”2

The way we respond to student misconduct symbolizes the kind of community we aspire to be. Just as criminal justice officials have learned they cannot incarcerate their way out of the crime problem, campus conduct officers know they cannot suspend their way out of their student conduct problems. Restorative justice offers a different approach that is educational for the student offender while also meeting the needs of the harmed parties and the institution.

2.

The Principles of Restorative Justice

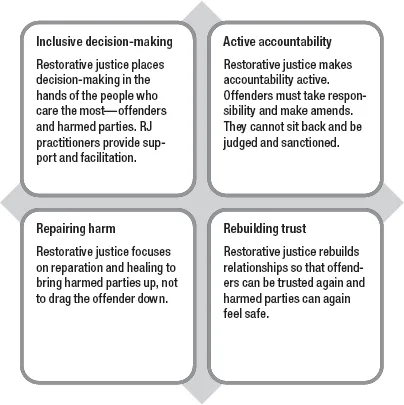

The Spirit Horse case illustrates four principles that are central to restorative justice.

Inclusive decision-making

Inviting offenders to voice their ideas about how to repair the harm and asking victims and affected community members to articulate the harms they experienced and what needs they have—inviting them all to play a central role in creating a sanctioning agreement—illustrates the first core principle in restorative justice: inclusive decision-making.

Sitting in a circle with facilitators who help guide the conversation but who do not offer ideas or solutions of their own, harmed parties and offenders play new and very different roles in the decision-making process than what is common in other campus conduct and judicial processes.

Consider, for example, the roles they play in the criminal courtroom. Defendants have a place to sit, but it is their attorneys who speak on their behalves. Crime victims have no place except as observers in the gallery. And for witnesses, even the observer role is denied.

The most dissonant role in the courtroom is that of defendants, nearly asleep at their own trials, with nothing to do and little understanding of the technical language that is being spoken, which is so decisive regarding their fates. In the restorative process, the student offender, the artist, the storeowner, and the arts director are not marginalized observers, but central actors in the drama of decision-making.

On college and university campuses, the standard disciplinary process is typically offender-centric. Most often, a single conduct officer will meet with the student, discuss the incident, and decide on the spot what the sanction will be. Sometimes a conduct board will listen to the facts as presented by the offender and a complainant, but the board will send them to a waiting room while it privately deliberates about the sanctions. Offenders and harmed parties do not have a strong voice in this process.

Because the artist, storeowner, and arts director are not members of the campus community, it is not likely that they would have been invited to participate or even hear about the outcome of the Spirit Horse case. They would not have learned of the campus’s concern about the incident, and they would not learn anything about the student that might offset the negative stereotypes promoted in the local newspaper. They would not have been able to share the varied ways in which they were impacted by the incident and what needs and concerns they had after what happened.

Active accountability

Secondly, restorative justice focuses on active accountability. Offenders must take active responsibility for their transgressions. Often, in our criminal justice or campus conduct proceedings, offenders are able to distance themselves emotionally and remain quite passive.

The archetypal image is a young man sinking down in his chair w...