![]()

Chapter 1

The Dynamic Potential of Urbanism Without Effort

AS URBAN STAKEHOLDERS—residents, pundits, developers, associated professionals, and politicians—we like to discuss and debate aspects of urbanism1 and how cities should change to meet new challenges. But when we talk about urbanism, I think we often forget the underlying dynamics that are as old as cities themselves. As a result, we favor fads over the indigenous underpinnings of urban settlement and our own, thorough observations about urban change. We focus too literally on conclusory plans, apps, model codes, transportation modes, building categories, economic and population specifics, and summary indicators of how land is currently used. While we might appropriately champion the programmed successes of certain iconic examples, we risk ignoring the backstory of urban forms and functions and failing to truly understand the traditional relationships between people and place.

I believe it is critical to first isolate spontaneous and latent examples of successful urban land use before applying any data-driven inquiries, prescription of typologies, desired ends, or governmental initiatives. Such inspirational “urbanism without effort” is the premise of this book and its illustrations, as well as the basis for a clean, multidisciplinary slate for reinvigorating the way we think about urban development today.

The Definition

This premise needs a definition and reference point for all that follows here and in future inquiry. Urbanism without effort is what happens naturally when people congregate in cities—based on the innate interactions that urban dwellers have with one another and with the surrounding urban and physical environment. Such innate interactions are often the product of cultural traditions and organic urban development, independent of government intervention, policy, or plan.

Urbanism without effort is not always initially obvious; it may seem more whimsical than remarkable when viewed from an aerial photo, an online map, or a satellite picture. In fact, it is almost invisible from these perspectives, as the fine urban grain is lost. It is best recognized and embraced from the ground and experienced firsthand, where it is possible to see more than just the physical outline of the city—it is possible to see life flowing through the urban form.2 This familiar, firsthand perspective, often informed by photography, focuses on organic and naturally occurring urbanism, as distinguished from other typecast, purposeful approaches, such as tactical, lean, interventionist, insurgent, or “pop-up” urbanism.3

Figure 1–1: This wall in Paros, Greece, is composed of basic materials left over from previous structures. It shows the fundamental human adaptive spirit at its sustainable best—in local context.

Figure 1–1A: Portions of Seattle’s older brick streets remain in certain parts of the city, complemented by more modern pavement types.

While these more purposeful approaches—and associated demonstration projects—may lead to successful places, I often wonder, why don’t they always have a meaningful and lasting effect? All too often these approaches are more sensational than not, overly superficial, or temporary by design.4 And, unless calibrated to the local context, the status quo frequently returns after these purposeful installations, such as street-side tables, greened parking spaces, food trucks, or guerrilla gardens, are removed or abandoned. In comparison, urbanism without effort endures beyond a mere installation or exhibition. Because it is latent rather than faddishly imposed, it can grow and evolve based upon a more historical, authentic, and robust foundation.

Rather than assume that the popular and touted is readily adaptable everywhere, or readily subject to apps, metrics, or labels, we should return to first principles and isolate the fundamental, vernacular relationships between city inhabitants and what surrounds them. We need to look, analyze, and discern, until we remember what a basic and familiar sort of city life looks like. While we consider these inherent factors that shape spaces and their use, we also must remember that there is a certain spontaneous magic attributable to good urban places that can awaken them but will only occur when they are locally relevant and embraced.

The Premise and the Pictures

To assure a successful and meaningful return to first principles, we each need a renewed and fine-tuned qualitative emphasis—our own, image-rich “urban diaries”—over and above the many thoughtful urbanist measures, such as Walk Score,5 Place Score,6 StreetScore,7 or even the conjectural JaneScore.8 It is time to look at cities in a more holistic way9 that better explicates today’s often irrational fusion of the planned, the spontaneous, and the natural—and to understand the city as “an artefact [sic] of a curious kind … more like a dream than anything else,”10 including experiences of place that are “a rainbow well within our grasp.”11

Urban diaries play an important thematic role in this book and its more applied companion, Seeing the Better City,12 as an ongoing source of urban documentation and understanding. While they may sometimes be figurative, or emerge from an internalized memory or intuition, they may also take the form of a notebook, a scrapbook, a sketchbook, or a digital file displayed by computer or tablet that reflects changing views of the city over time.

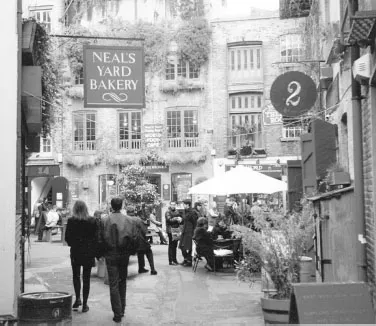

Figures 1-2 and 1-2A: Human-scale public spaces create a sense of belonging and comfort. The concept is effortless to experience and imagine, as well as a predicate to policy, regulation, and implementation. In a city, stumbling upon—and recording—places like Neal’s Yard is undeniably special and can create indelible memories that fit today’s dialogue of urbanism. These photos, taken 16 years apart (1997 and 2013), show notable redevelopment, but this small courtyard in London’s Covent Garden section retains a time-honored focus on holistic-health restaurants, shops, and businesses—accessible through a narrow passage off of Monmouth Street—a reminder of why walking-oriented guides or articles are often the best “radar” to use for touring a city.

No matter what form an urban diary may take, I believe (and Seeing the Better City explains and applies) that well-composed, onsite photographs are an essential part of documenting holistic urban observation, beyond the removed convenience of Google Street View. Whether immediately tangible or a picture in the mind, such imagery can re-create what political writer Alexander Cockburn once termed “the lost valleys of the imagination.”13

Legendary travel photographer Burton Holmes aptly used the phrase “film as biography” to describe photographs that authentically capture another time or another place.14 To me, that term infers principles of practice for regulation and design that are easily observed from images of real and foundational places. In particular, the architect is able to derive the relation between building and street. The traffic engineer finds inspiration for lanes, surfacing, and signage. The lawyer and planner see building setbacks and the means to encourage pedestrian spaces while assuring light, air, acceptable noise levels, and governance of private use of public spaces.

No doubt, I inherited this point of view from my father, who was an urban planning professor. While growing up, I watched him photograph, with an East German Exacta, for purposes of his later sketching, teaching, and advocating the role of urban imagery. In a 1965 article, he argued that several landmark studies of American communities (e.g., Lloyd Warner’s Yankee City15 and Robert and Helen Lynd’s Middletown16) partially missed the mark because they lacked diagrams and pictures.

Many social studies of communities refer implicitly or explicitly to urban form without so much as a picture, map or diagram. Yet visual material can make a contribution to understanding the urban environment itself, the interrelationship of society and environment, and the development of techniques for study and communication.17

Figures 1-3 and 1-3A: Urban diarists collecting information in Lisbon and Marseilles.

Figure 1–4: Rovinj, Croatia, by author at age 13; honoring the water.

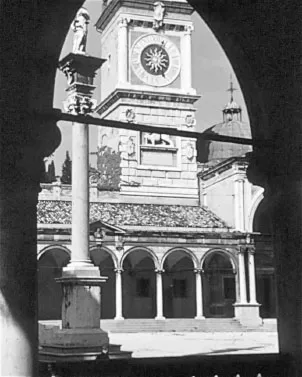

Figure 1–5: Udine, Italy, by author at age 13; important public place.

My own 1968 photographs from Slovenia, Croatia, and Italy (partially shown here) document my first interests in reading the city for myself, something we can easily do on a much larger, more shareable scale today with smartphones and social media platforms such as Instagram and Facebook. Even without digital outlets, as a teenage beneficiary of my father’s academic research, I was drawn to the differences I saw in foreign cities that predate my native Seattle by more than 1,000 years, specifically the following:

- Cities that organized around important public places, like churches and squares and towers

- Monuments located in these public places, some new and some that have been there a very long time, to honor people or events from history

- Notable walking areas where people were separated from cars

- Citi...