![]()

PART I: CHINA-BURMA-INDIA

1. Monsoon Madness

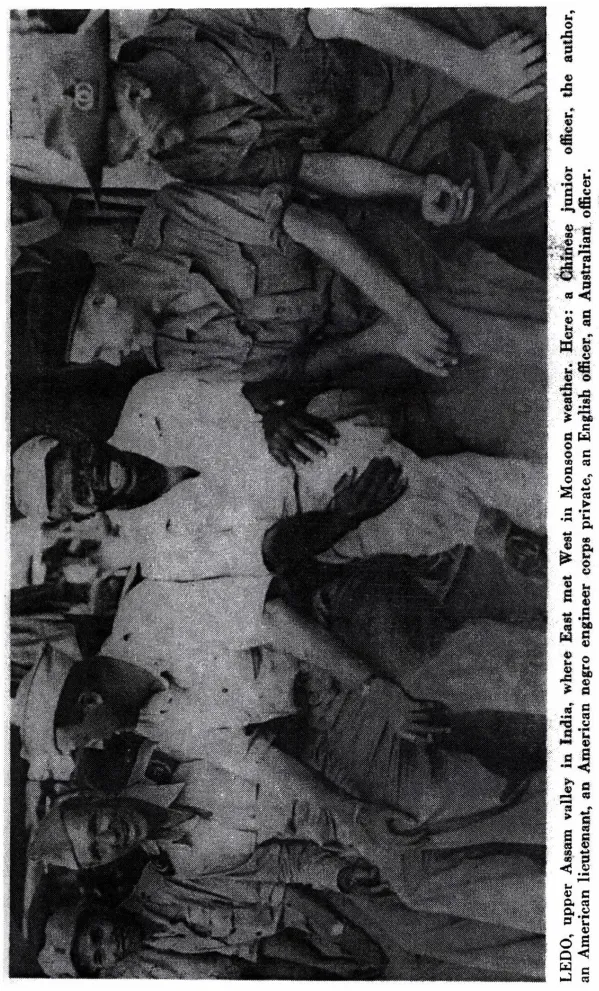

GENERAL JOE STILWELL, a great soldier and a true American, sat in a tent on a hillside at Shaduzup and told me about the war in Burma. It wasn’t going well in that spring of 1944. No army ever had tried to move through Burma in monsoon weather. Experts said it couldn’t be done—all except General Stilwell.

The tall white-haired General had infinite faith in the Chinese people and unbounded hatred of the Japanese army. He had been chased out of Burma in 1942, a remarkable long-distance trek north from Rangoon with advance units of the notorious Japanese 18th division at times surrounding his little band in the jungles. Stilwell knew Gen. Renya Mataguchi who had led the 18th into the battle of Hangchow bay in 1937. They had met frequently prior to the war when Stilwell was stationed in Shanghai.

There was a long score to settle. The Japanese 18th had moved from Hangchow to Nanking. It led the assault that took Shanghai. When the Japs hit us at Pearl Harbor the 18th was poised for one of the most dramatic phases of the early years of war, the steady march through the Malay jungles into the mighty city of Singapore. From there the 18th moved on to lead the attack that captured Rangoon—and sent Stilwell and his small military detachment fleeing for their lives. Small wonder Stilwell had uttered the frank statement characterizing the early results of American troops in action: “We took a hell of a beating.”

With Stilwell on that 1942 retreat were two Chinese divisions, the 22nd and 38th. They were typical Chinese troops, poorly armed, half-starved, miserably officered. The General, bitter and determined on revenge, took the remnants of the two divisions to a camp at Ramgavr near Calcutta, brought in American officers as instructors and went to work. Never did he deviate from a plan which combined military necessity with revenge—a campaign to drive the Japs back south in Burma thus opening a supply route to China; and to administer a sound whipping to General Mataguchi who had been relieved of command off the 18th division and given full charge of operations in Burma.

So again in 1944 it was Stilwell against Mataguchi. Those two Chinese divisions, along with Gen. Frank Merrill’s famous Marauders fought one of the most remarkable campaigns of this war. On Feb. 7, 1944 they crawled up the rugged mountains of north Burma and started a trek of more than 180 miles, headed for Myitkyina, fighting Japs every foot of the way day and night.

The Marauders had fought on Guadalcanal or trained in Puerto Rican jungles. They were perhaps the roughest don’t-give-a-damn outfit of the whole American army. And the Chinese with them were no less canny and courageous. It was terrific campaign, for the Japs were dug in, the jungles steaming and filled with malaria, jungle rot, booby traps, snipers who lurked in trees. Often they were am-bushed—and fought out. Time and again bands off Jap fanatics stayed behind, courting certain death but in position to blaze away with their deadly Nambu machine guns until withering fire cut them down.

It was a sadly depleted army that finally chased the Japs off the Myitkyina airstrip. Fatigue and illness had taken the greatest toll. The records will show that the Marauders ended forever the old belief that the Jap is a superior jungle fighter. The Marauders were better shots, learned jungle fighting, out-foxed the Japs time after time and left a trail of dead through the jungle.

When I arrived at the Burma front the Eastern campaign wasn’t getting much attention. Everybody at Home and in England was waiting for Allied invasion of France. And a great soldier sat discouraged in his tent that afternoon in Burma, the monsoon beating furiously all around us. Good soldiers weren’t coming East fast enough. In fact good soldiers weren’t coming at all.

“Merrill’s men and the 22nd and 38th Chinese were so worn out I had to relieve them when we took the airfield,” Stilwell said, “I had sent for a good regiment drilled for jungle war. I got casuals, and after four days had to pull ‘em out.”

The full significance of General Stilwell’s statement didn’t hit me until I flew down to the airfield next day and saw what was going on. There, 1,500 yards behind the battle front American troops were getting routine infantry drill in an open meadow, going to the rifle range every afternoon. Such a scene—troops from the greatest nation in the world getting basic training in the middle of a World War at the front during a big campaign. It couldn’t happen, but there it was!

This was one phase of the action I dared not write. In fact the censors in the CBI theater were most touchy young men who seemed to find great pleasure in figuring out how copy might comfort the enemy.

Here’s what had happened. Instead of sending a regiment of trained troops to General Stilwell some army decision in America sent a few thousand men culled from signal, ordnance, quartermaster, medical, and engineer corps. There were drummers, buglers, artists, air corps washouts—officers and men too. Gen. Gilbert Cheeves later told that when the troops reached Calcutta they didn’t even have rifles. He issued arms and ammunition and sent them on.

The Marauders were relieved at the Myitkyina airfield by these green troops, flown in straight from Calcutta. When they got off the planes the field was under Jap machine gun fire—and half of them didn’t know how to put a clip of shells in a rifle. They didn’t even know their officers, who were no more trained than they. Perhaps in all history of war a sadder tragedy is not known.

Those troops were thrown into foxholes the Marauders had vacated during the night. Two green Chinese divisions replaced the worn-out veteran Chinese. During the night they added to the general tragedy when one regimental leader read his compass wrong and soon had his men under fire of another Chinese regiment. Each unit, thinking the other was an advancing Jap outfit, fired all night—and in the morning discovered both virtually were annihilated.

The green American troops went into low grassland and jungle on the north edge of Myitkyina. The alert Japs soon learned they weren’t facing the fearsome Marauders any longer. So they let our inexperienced patrols virtually step on them in the jungles. The patrols would report the area cleared of Japs, next day a company or two would move in—and few ever got out. They were shot down, left to the mercy of insects which ate them alive, became lost and wandered screaming through the woods until they went mad, fell into Jap hands and were tortured to death: a sorry blot on the pages of American military.

Col. C. N. Hunter (who had taken over when his skip-per, General Merrill became ill), saw something had to be done—but fast! American and Chinese troops had carried out a magnificent campaign straight to the gates of Myitkyina. Any kind of organized assault would have completed the Jap defeat two days after the airfield fell. But the Japs, quick to sense the change in both American and Chinese troops, dug in quickly and reinforcements came up from Mandalay, hoping to surge back northward and retake all Stilwell had gained.

![]()

2. Chinese at War

“EVERY NIGHT down here is Fourth of July,” explained the sergeant as I looked in questioning wonder at the fireworks over Myitkyina just after dark. The sky was filled with flares. Tracer bullets sailed majestically toward the stars. The rattle of machine guns and the soft “plunk” of exploding mortar shells came across the plain to the airstrip.

The Chinese and Japs had started their evening exchange of souvenirs. Chinese regiments at Myitkyina were boys with new toys—rifles and machine guns and mortars. They also had military flares, and a good supply of Chinese fireworks. So, every evening at dark they began to shoot.

But for the fact that many were being killed and wounded ‘twas a comic opera war.

The armies battled fiercely during the day, with our planes aloft most of the time to bomb and strafe, our artillery booming, our front line troops sniping, rushing pill boxes, repulsing occasional Jap patrols.

The Japs had an old 77mm cannon they used sparingly. One day a new chaplain came down to the airport and nobody thought to stop him as he posted notices on all bulletin boards telling of a Mass at 7:30 next evening on the airstrip just outside the warehouse door. Some 300 worshipers dutifully gathered and at 7:35 the Japs dropped some shells a few yards from the padre, killing two and wounding several more. Some spy—the camp was overrun with refugees and nobody ever knew which side they were on—had read the notice and, slipped into the Jap lines. We lay in our water-soaked holes for hours that night.

Somewhere in the Jap lines was a machine gunner we called Typewriter Joe. He had the night shift. His first act was to fire a peculiar burst on his Nambu, always the same. When we heard that we knew it was 5:30, so everybody, Japs and Chinese, went to chow.

From 5:30 until dark the war front was quiet as a country meadow. The boys ate their rice and greens, the Chinese being great hands for collecting various leaves from the fields. After chow they sat around smoking, and occasional voices from across no man’s land told us the Japs were doing the same. Then some Chinee would decide ‘twas dark enough to try a flare. Another Chinee would shoot tracer bullets at the flare hanging in the sky, the Japs would reply with a few bursts of gunfire, a few flares—and pretty soon the night would be filled with a crazy patchwork of darting fire.

I wasn’t much impressed with the army at first: neither the Chinese nor our own command. Two brigadiers were there, General Wessels who was in command and General Arms who wanted to be. General Wessels was afraid to protest because General Stilwell had sent General Arms into camp along with 50 other officers the Japs had chased out of China where they had been instructing Chinese troops. So we had officers all over the place and not enough riflemen to attack.

My first trip to the infantry front was with General Arms. At breakfast he said, “if you want to go with me, I think we’ll have these Chinese moving pretty fast.” That was just what the Chinese had not been doing with great enthusiasm, so I went along. We jeeped out to a Chinese regiment and General Arms said, through his interpreter (we had 50 or more Chinese students, intellectuals, who thought Hemingway and Steinbeck represented the true America, as interpreters); “Tell General——that General Arms wishes to speak to him at once.” We sat half an hour in the stifling heat of a low dugout, General Arms’ temperature rising each time he wiped his forehead. Finally in stern tone he cried, “Tell General——he has kept me 30 minutes and the American general will not be kept waiting. I want him here at once.”

Some 30 minutes later the Chinese general came in.

“General, you’ve kept me waiting an hour,” cried General Arms, “General Stilwell will be very angry.”

The interpreter spoke. The Chinese general spoke. The interpreter turned to General Arms. “General——say ‘so sorry’” he reported. After which General Arms got down to business. He threw the Ft. Benning infantry school rule book at the Chinese general. It was duly interpreted (I suppose) and the Chinese general smiled politely, nodded agreement and flicked ashes from a cigarette held in a beautiful ivory holder.

“Now, I want——” ordered General Arms, and proceeded to tell the Chinese leader what to do with each unit. General Arms pulled out his watch. “It is 10:30,” he said. “We will move at 11. Order your battalion commanders accordingly.”

“Of course,” agreed the Chinese. Then General Arms called for artillery at 10:55, a five-minute preparatory barrage. It came. So did 11 o’clock—and all was quiet. General Arms stormed. General——sat quietly inscrutable. Minutes passed, 30 in a row.

“You did not move your troops,” thundered General Arms.

“It was not advisable,” said General——“Perhaps tomorrow.”

“But I order you to attack. This is war!” ordered General Arms, and he stood up to add emphasis to the command, bumping his head severely on the bamboo ceiling.

“So sorry,” replied the Chinese, “Perhaps tomorrow w...