eBook - ePub

Blockchain Economics: Implications of Distributed Ledgers

Markets, Communications Networks, and Algorithmic Reality

Melanie Swan, Jason Potts;Soichiro Takagi;Frank Witte;Paolo Tasca

This is a test

Compartir libro

- 320 páginas

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Blockchain Economics: Implications of Distributed Ledgers

Markets, Communications Networks, and Algorithmic Reality

Melanie Swan, Jason Potts;Soichiro Takagi;Frank Witte;Paolo Tasca

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

This practical introduction explains the field of Blockchain Economics, the economic models emerging with the implementation of distributed ledger technology. These models are characterized by three factors: open platform business models, cryptotoken m

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Blockchain Economics: Implications of Distributed Ledgers un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Blockchain Economics: Implications of Distributed Ledgers de Melanie Swan, Jason Potts;Soichiro Takagi;Frank Witte;Paolo Tasca en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Business y Investments & Securities. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Categoría

BusinessCategoría

Investments & SecuritiesPart 1

Economic Theory and Market Structure

Chapter 1

Blockchain Economic Theory: Digital Asset Contracting Reduces Debt and Risk

Melanie Swan

Purdue University, USA

Abstract

Disparate aspects of the emerging Blockchain Economics paradigm have been discussed, particularly cryptotokens and Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs), however, a comprehensive picture of the greater economic transformation unfolding with blockchain technology has not yet been articulated. This chapter proposes a Blockchain Economic Theory of Digital Asset Contracting as an explanatory model. The central argument is that blockchain-registered digital assets can be transacted instantaneously and pledged in new ways. This advance is leading to new modes of contracting (smart contracts) and new forms of money (cryptotokens), which in turn facilitate new structures of financial interaction. Distributed ledgers and blockchain-based structures might be applied to structural economic problems such as debt, systemic risk, technological job outsourcing, entitlements overhang, healthcare cost-outcome disconnects, and financial inclusion. A key innovation is Payment Channels, which enable the use of capital on a net rather than a gross basis, which might eventually lead to a restructuring of debt burdens.

1.1Introduction

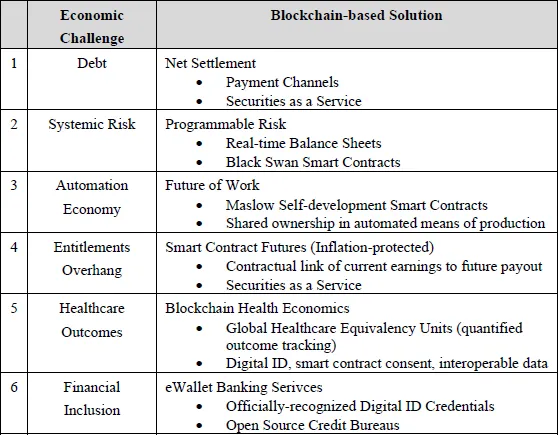

While not a panacea, one litmus test for blockchain technology could be the extent to which it might be used to address structural economic problems. Existing challenges include debt, systemic risk, an orderly transition to the automation economy (technological job outsourcing [Swan, 2017a]), entitlements overhang, a disconnect between healthcare costs and outcomes, and financial inclusion. Table 1 enumerates outstanding economic challenges and potential solutions using blockchain technology. This chapter discusses the challenges and solutions in the form of a causal model.

Table 1.Economic Challenges and Potential Blockchain-based Solutions.

1.2Blockchain Economic Theory: Digital Asset Contracting

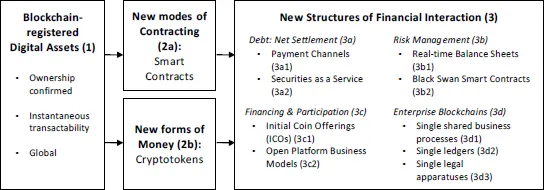

A Blockchain Economic Theory of Digital Asset Contracting is proposed. The theory presents the distinguishing features of the emerging Blockchain Economics paradigm in the form of a causal model to explain the relationships between the elements (Figure 1). The premise is that blockchain-registered digital assets lead to new modes of contracting and new forms of money, which facilitate new structures of financial interaction. Framed more formally, the hypothesis is that the dependent variable (structures of financial interaction), is influenced by the independent variable (blockchain-registered digital assets), and further affected by the moderating variables (modes of contracting and forms of money).

Figure 1.Blockchain economic theory of digital asset contracting.

Outlining the model in detail, blockchain-registered digital assets (1) have the novel functionality that asset ownership is already confirmed, which means that they can be transacted instantaneously, on a global basis. Digitally-registered assets can therefore be pledged in new ways which leads to new modes of contractual relationships between parties (smart contracts) (2a) and new forms of money (cryptotokens) (2b). New modes of contracting and new forms of money facilitate new structures of financial interaction (3). Regarding debt (3a), there is the possibility that capital might be engaged on a net rather than a gross basis with vehicles such as Payment Channels (3a1) and Securities as a Service (3a2). Risk management (3b) could be enhanced with Real-time Balance Sheets (3b1) and programmable risk Black Swan Smart Contracts (3b2). Cryptotokens lead to new modes of financing and participation (3c) such as Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) (3c1) and participative Open Platform Business Models (3c2). Enterprise Blockchains (3d) configure the possibility of single shared business processes, ledgers, and legal apparatuses (3d1-3). Decentralized methods of contracting and economic orchestration are an extension of digital models more generally. Already with the widespread implementation of the Internet, regulators realized the evolutionary implications of digital network technologies for central banking, including global settlement, and a much smaller institutional footprint and control apparatus for monetary transfer [King, 1999; Ize et al., 1999].

1.3Blockchain-Registered Digital Assets (1)

Distributed ledgers mean that assets (both physical and digital) can be registered to blockchains for confirmation, control, and transfer. Enforcement mechanisms for connecting physical assets to electronic transfer are non-trivial [Dupont, 2017; Nelson, 2017], but not discussed here. For economic theory, the point is that blockchain-registered digital assets have a heightened mode of exchange. Assets exist in a state of readiness for transfer with the ownership of the asset and the identity of the owner pre-confirmed. Blockchain-based assets should be understood as having the property of being instantaneously transferable, including per digital contractual arrangements. A variety of digitally-enabled and automated transfer mechanisms are made possible. The network-confirmed ownership is the salient mechanism for how parties who do not know each other can nevertheless become contractually obligated. A bank or lawyer is not needed as an intermediary; the network software instantiates the contractual relationship for the peer-to-peer transaction. The principles of the instantaneous digital transferability of assets and the real-time confirmability of identity credentials enable new modes of contracting between parties (2a) and new forms of money (2b).

1.4New Modes of Contracting: Smart Contracts (2a)

To be legally binding, a contract typically has four elements: two or more parties to the contract, financial consideration, and terms. A smart contract is a contract registered to a blockchain, including for some portion of its execution to be automated [Swan, 2015]. For example, the interest rate on a floating-rate mortgage is reset on a monthly basis. Resets are orchestrated digitally at present, and could be further automated with greater transparency with blockchain-based lookup processes using oracles (independent data providers). The interest rate reset might be a standard smart contract process calculating the rate as Libor + 150 basis points (1.5%). Blockchain technology might start to be used to coordinate both the initial asset registration and transfer process, as well as the ongoing execution of financial contracts. The implication is that the economy could become increasingly digitally operated. Electronic signatures and digital contracts are legally binding in many geographical domains, enforced in the U.S. through the E-Sign Act (2000) [Stern, 2001] and globally with the UN’s Model Law on Electronic Commerce [1996]. The future incarnation of digital contracts could be blockchain-based smart contracts.

1.5New Forms of Money: Cryptotokens (2b)

Cryptotokens constitute a new kind of money. Conceptually, cryptotokens are “money +” in that they confer the usual functions of money plus additional community participation features. The three tradition functions of money are serving as a medium of exchange, a store of value, and a unit of account. Cryptotokens are a new form of digital money, which have these standard aspects together with additional functions. Definitionally, cryptotokens represent a particular fungible and tradable asset that is found on a blockchain ledger [Investopedia, 2018a]. Digital tokenization is the process of creating cryptotokens by turning an asset, right, or good (digital or physical) into a tradable unit, and instantiating the asset on a blockchain for its exchange. Cryptotokens are a more complicated and feature-rich form of money that is also a tool for enabling participants to undertake more actions within an economic community, in particular, to earn money, access resources, and vote on decisions.

Cryptotokens could inaugurate a new phase for how individuals expect to interact with Internet-based communities. In blockchain communities, the expectation may be to have both economic and governance participation. The Ethereum project District0x is an example of such a community. A key incentive for users to join a crypto community could be that there is economic participation in terms of an accounting system that tracks and rewards contributions, and a voice in community governance through voting, decision-making, and the ability to propose and discuss initiatives. Rewards for contributions could include earning royalties whenever user-created content is used (e.g. software code, music, art). Community members could likewise pay to access community resources (e.g. content, file storage).

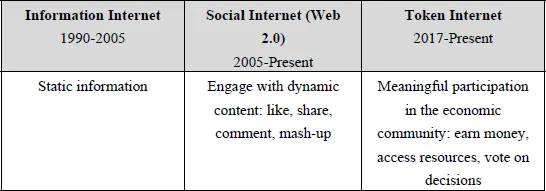

Table 2.User Participation Expectations in Internet-based Communities.

Table 2 considers the evolution of user expectations when engaging with web communities. Initially, websites presented static information, and there was no possibility of interaction. Then, with the social web, users started expecting to be able to “like,” comment, share, and interact with dynamic content and other community members [O’Reilly, 2005]. Now in a third phase, what it means to be a token project is to engender the notion of a participative economic community. Tokens are a means of providing remuneration to those who participate in the community and add value. A greater vesting of responsibility and intensity of community participation is enabled, literally allowing members to “put their money where their mouth is” (i.e. contribute economic resources to areas of concern). This is precisely the greater economic and political self-definition that Kant calls for in What is Enlightenment? [1794]. Blockchains enable us to rethink who we are as subjects, configuring the sensibility of the cryptocitizen as one who thinks freely from the dictates of authority [Swan, 2018b].

1.6New Structures of Financial Interaction (3)

1.6.1Debt: Net Engagement of Capital (3a)

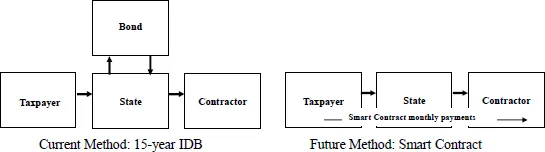

Traditionally, capital has been engaged at the gross, not the net level. Net settlement is a settlement system between parties in which transactions are accumulated and offset against each other, with only the net difference transferred. Most national and international banking and payments systems, however, operate on a real-time gross settlement (RTGS) basis. Significant financial operations also engage capital at the gross level, for example fundraising. A municipality building a bridge borrows the whole amount needed in an Industrial Development Bond (IDB) (Figure 2). However, with digitally-registered blockchain assets, new kinds of arrangements might be possible to engage capital on a net basis [Swan, 2017b]. The economic question is to what extent public sector activity might be instantiated in distributed ledgers. The public sector currently comprises 15% of OECD economies federally [Baddock et al., 2015], plus 14.2% at the state level in the U.S. [Frohlich and Kent, 2015]. Overly large public sectors have been shown to hamper growth [Olson, 1999].

Smart contracts might be employed to address the time lag between current and future cash flows such that capital could be pledged and transferred in smaller more regular payments. In the bridge example, smart contracts could match expected tax receipts with cost outlays for the bridge construction. In principle, a bond offering might not be necessary with directed tax receipts. Smart contracts could transfer weekly tax receipts from constituents to contractor construction expenses. In a more efficient system, real-time finance could be a possibility. Blockchain-based contractual structures might enable capital to be utilized more effectively. One benefit could be offering an alternative to the monolithic structure of debt, a problem affecting sovereign states [Zumbrun, 2017; Frewen, 2010], institutions [Choudhry et al., 2014], and individuals [Sweet et al., 2013] alike.

Figure 2.Structure of municipal finance: bonds could become smart contract pledges.

Net settlement is not a new concept. Before central banking, there was an historical precedent for net settlement amongst parties and free banking systems (meaning a plurality of banks each issuing their own notes). Societies with more equitable distributions of power were more likely to have net-settled systems. Notable examples include Canada (1800-1935), Sweden (1831-1902), and the Fukien province in China (1644-1911) [Selgin, 1988, pp. 7-15]. White describes English and Scottish free banking (1716-1845), particularly in the linen industry, where trust and a diversity of IOU instruments played a role in financing remote trade in the Scottish Highlands [1996]. Smith argues that net-cleared financial systems are less risky because self-preservation is more prominent [1990, pp. 178-184].a Banks having reciprocal claims on each other may instill greater financial responsibility than centralized methods. Selgin proposes a theory of free banking, suggesting that money supplies are more stable and resilient when there is competitive note issuance [1988]. Despite the historical precedent of net clearing, many countries were forced to adopt a centra...