eBook - ePub

Urban Land Rent

Singapore as a Property State

Anne Haila

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Land Rent

Singapore as a Property State

Anne Haila

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

In Urban Land Rent, Anne Haila uses Singapore as a case study to develop an original theory of urban land rent with important implications for urban studies and urban theory.

- Provides a comprehensive analysis of land, rent theory, and the modern city

- Examines the question of land from a variety of perspectives: as a resource, ideologies, interventions in the land market, actors in the land market, the global scope of land markets, and investments in land

- Details the Asian development state model, historical and contemporary land regimes, public housing models, and the development industry for Singapore and several other cities

- Incorporates discussion of the modern real estate market, with reference to real estate investment trusts, sovereign wealth funds investing in real estate, and the fusion between sophisticated financial instruments and real estate

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Urban Land Rent un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Urban Land Rent de Anne Haila en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Sozialwissenschaften y Städtische Soziologie. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

Introduction

Singapore as a Case and Comparison

This is a book about land, rent and state in Singapore. Singapore is an island city-state in Southeast Asia, situated between Malaysia and Indonesia. Its population in 2013 was 5.4 million; its landed area was 716.1 square kilometres and population density 7540 persons per square km (Yearbook of Statistics 2014). It became independent in 1965 after 140 years as a British colony (some colonial-time buildings still remind us of its colonial past, see Figure 1.1). In 1819 Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles, working for the East India Company, landed in Singapore and decided to develop what was a tiny fishing village lying on the sea route from The Spice Islands to Europe into a port city. After the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, ships between Europe and East Asia sailed through the Singapore Straits, making Singapore an important node in the maritime economy.

Figure 1.1 Colonial Singapore. Photo: Anne Haila.

Unlike prominent port cities that lost their role as trade routes shifted (places like Calicut, Alexandria, Goa and Malacca), Singapore was able to keep its place in international networks and grew into a prosperous world city. An often-cited reason for this has been Singapore's good leadership. Stan Sesser (1994: 12), for example, compared Lee Kuan Yew, the first and long-serving prime minister (1959–1990) and founding father of modern Singapore, to Mao Tse-tung, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, Ho Chi Minh and Sukarno, all of whom failed in the transition from revolutionary to ruler and left disorder in their wake. Lee was followed by Goh Chok Tong (1990–2004) and Lee Hsien Loong, the present prime minister.1 Their party, the People's Action Party (PAP), has been in power since 1959. Unlike in countries where elections change political programmes, Singapore has built itself step by step, as if there has been a logical plan. This makes Singapore function almost as a laboratory for a social scientist.

As is often the case with port cities, Singapore is an ethnically diverse city composed of Chinese migrants, immigrant labour transplanted by colonialists, and Western expatriates brought in by recent waves of globalisation. The first census in 1871 showed that there were already Malays, Javanese, Bugis, Boyanese, Chinese, Burmese, Indians, Klings, Bengalis, Europeans, Americans, Eurasians and Arabs (Chiew 1985). Today the census differentiates four groups: Chinese, Malays, Indians and Others (known as the CMIO classification). In 2012, there were 74 per cent Chinese, 13 per cent Malays and 9 per cent Indians. The rest were classified as Others.

Today Singapore is a cosmopolitan city where Chinese, Malay, Indian and European populations speak different languages and live close to each other. Its cosmopolitan atmosphere contradicts the image of Singapore as a boring and sterile place. Hawkers cook Chinese, Indian, Thai and Indonesian food on the street. Unlike in Helsinki, street walkers are tolerated in the main shopping street, Orchard Road, and, not so long ago, transvestites, depicted by James Eckardt (2006: 55) in his memoir Singapore Girl, made Bugis Street an ‘eternal theatre with actress and spectator the same person’.

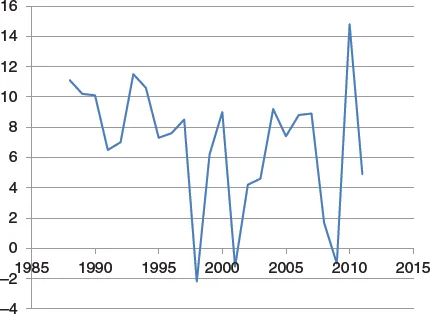

When Singapore gained independence in 1965, it was poor and underdeveloped. The prospects of a tiny city-state with a Chinese majority situated between two Muslim majority nations and without a hinterland, resources or industries were so poor that imagining Singapore as an independent polity was deemed inconceivable (Chua 1995; Leifer 2000). Contrary to pessimistic expectations, Singapore's economic rise since the 1960s has been astonishing and, together with Korea, Taiwan and Hong Kong, Singapore became renowned as one of the rapidly growing Asian ‘tigers’. Figure 1.2 shows Singapore's economic growth since 1988.

Figure 1.2 Singapore's GDP. Annual growth.

Source: The World Bank.

Economic growth until the 1997 Asian crisis was high and stable (between 6.5 and 11.5 per cent). Singapore became a favoured location for transnational companies thanks to its rule of law, predictable government institutions and good business environment. Singapore's domestic economy is small but it has a role in the global economy as a financial centre. For several years Singapore has been ranked as one of the world's most competitive economies. In 2013 the World Economic Forum ranked Singapore second after Switzerland. Year after year, the World Bank has ranked Singapore as the easiest place to do business. Among the criteria used by the World Bank are government regulations and protecting investors' rights.

After the Asian crisis, economic growth became unpredictable and less stable. To cope in the new global environment, Singapore introduced several new laws and began to change. Figure 1.2 shows three troughs: the 1997 Asian crisis, the burst of the dotcom bubble in the early 2000s and the 2008 subprime crisis. The 1997 Asian crisis was a turning point after which Singapore started liberalising its economy. Although there was a rapid recovery soon after the Asian crisis, there was a sharp recession in 2001 due to the downturn in the global electronics market. Singapore is not just a service economy, it has a significant manufacturing sector as well. In 2001, manufacturing formed 23 per cent of Singapore's economy, of which electronics was 36 per cent (financial and business services was 28 per cent) (Economic Review Committee Report 2003, MTI). The Gulf war and a SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) outbreak at the beginning of the twenty-first century worsened the situation. The third trough was in 2009. The subprime crisis in the USA and the global financial market turmoil affected Singapore's economy. The crisis in the Western financial market made speculative money flow into Singapore, increasing property prices and necessitating government intervention (see Figure 8.3).

Singapore is dependent on foreign labour. In 2013, the total population was 5.4 million, of which 1.5 million were foreign workers, expatriates or students. A white paper on population released in 2013 projected that the population could rise to 6.9 million by 2030, and the number of foreigners to 2.5 million. The white paper anticipates Singaporeans becoming more educated, taking managerial, executive and professional jobs. Hence foreign workers are needed to provide healthcare, domestic work, care for the elderly and construction work.

Compared to its Asian neighbours, who from time to time close their doors and isolate themselves from the world, Singapore consistently attracts foreign talent, is open to imported influences and adapts quickly to new trends. Occasionally, foreigners taking the jobs of Singaporeans (and simultaneously escalating housing prices) have stirred up discussions and led to tighter employment regulations, but foreign workers have been welcomed and leaders defend Singapore's open door policy. In 1997 Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said: ‘Let's say, for the sake of argument, you bring in Bill Gates. Will he take away the job from a Singaporean entrepreneur? I don't think so. He will bring in his business. If Microsoft starts up here with 2,000 employees, that's 2,000 extra jobs created’ (Chua M H 1997: 39).

Singapore's economic development has been complemented by social development. Slums were demolished and people were moved to public housing. In 2012, 82 per cent of the population lived in public housing, 12 per cent in condominiums and other apartments and 6 per cent in landed properties (resident households by type of dwellings, Yearbook of Statistics 2013). The state appropriated and reclaimed land and established a powerful housing authority, the Housing Development Board (HDB), to develop public housing (which also benefitted transnational companies locating in Singapore). A compulsory savings scheme, the Central Provident Fund (CPF), offered a generous savings rate and gave the government revenue for investment in infrastructure and public goods, explaining an astonishingly high homeownership rate of 90.1 per cent in 2012 (people were allowed to use their pension savings to buy housing). A staggering 82 per cent of the resident population lives in public housing and 90.1 per cent are homeowners: this book explains this paradox that contradicts Western scholars' image of public housing.

Singapore's built environment is as amazing as its economic rise (see Figure 1.3 of one of the imaginative new buildings). It is a collage of modernist housing estates, iconic office skyscrapers, luxurious shopping malls, five-star hotels, industrial estates and conserved shop houses. The government, advertising its land sales in newspapers abroad, has invited foreign developers and architects to build Singapore. Since the mid 1970s, Singapore's architecture has been dominated by foreign architects (Powell 1989: 13). World famous architects such as Moshe Safdie, I. M. Pei, Kenzo Tange, John Portman, Paul Rudolf,and Zaza Hadid have designed their signature buildings in Singapore. Among its eye-catching buildings is the durian-shaped opera house and three skyscrapers topped by a ship-shaped structure.

Figure 1.3 The durian-shaped opera house. Photo: Anne Haila.

The government has an important role in Singapore's economic and social development. Government expenditure relative to gross domestic product (GDP), however, is low in Singapore compared to other countries. Between 2000 and 2009, total government expenditure was about 16 per cent of GDP, which is low compared to OECD countries (from 30 per cent to 50 per cent) (Tan et al. 2009: 18). Yet the government is present in other ways. It intervenes and regulates, issues comprehensive plans, and its investment corporations and companies are globally operating companies bringing revenue to Singapore. The state owns 90 per cent of the land and produces public housing and industrial space. Government expenditure on healthcare is low (3.5 percent of GDP in 2005,Tan et al. 2009). This low figure does not, however, give a fair picture of Singapore's welfare policy, because healthcare is covered by a compulsory individual savings system (Medisave), while extensive public housing provides a safety net.

High economic growth, a competitive economy, a majority of people living in public housing and being homeowners, a cosmopolitan atmosphere, a futuristic built environment and the omnipresent government make Singapore a distinctive city that defies easy categorisations. Some studies, such as Peter Rowe's (2005) East Asian Modern, group Singapore together with East Asian cities in China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan, even though Singapore is located in Southeast Asia. Some other studies, such as Malcolm McKinnon's (2011) Asian Cities, exclude Singapore explicitly because it differs from other Asian cities. How to make sense of such a unique city? There are four traditions from which Singapore could be approached: comparison from the point of view of the West; Asian studies seeing Singapore from the perspective of Asian cultures; urban studies comparing Singapore to other global cities; and Singapore as a developmental state.

European Classics and Western Theories

European classics used Asia in order to understand Europe. Max Weber compared Asian and European cities, and through this comparison formulated his definition of the city: an urban community has a fortification, a market, a court of its own (and at least partially autonomous law), associations of urbanites, and an administration by authorities whose election involved the burghers (Weber 1966: 81). By contrast, Chinese cities were, in Weber's imagination, the seats of central imperial authorities where urban dwellers belonged to their families, native villages and temples. Weber concluded that an urban community, in the full meaning of the word, appears as a general phenomenon only in the Occident. Another European scholar, Fernand Braudel, asked why change was a striking feature of European cities, whereas cities elsewhere in the world had no history and were like clocks endlessly repeating themselves (Braudel 1973: 396).

Weber and Braudel praised the superiority of European cities over Asian cities. The glorification of Europe was even more obvious in the theories of oriental despotism invented to showcase European democracy. Montesquieu, who in The Spirit of the Laws (1748) introduced three types of government – republic, monarchy and despotism – presented ‘oriental despotism as an ideal type that had fear as its key value, in which there was no secure private property, the ruler relied upon religion rather than law, and the entire system was essentially static because of the dominant role of custom and taboos’ (Pye 1985: 8). Karl Wittfogel (1957) further developed Montesquieu's idea and connected despotic state power in Asia to the necessity of controlling floods and arranging irrigation, along with the absence of private property and civil society.

Empirical research in the wake of Weber, Braudel and Wittfogel has tested the speculative ideas of these European classics. Historians of China have found evidence, some to support Weber's speculations, some to disprove them. Faure (2002), for example, explained why cities were less autonomous in China by referring to the imperial examinations system that sent literati around the country spreading the influence and control of the central state, and to the Chinese way of organising the community around the family temple rather than forming an urban community. As to Southeast Asia, Weber was right. Fortifications were needed in Europe to protect towns from pillage by marauding bands of Vikings, Moslems, Magyars, pirates and brigands (North and Thomas [1973] 1999: 19); in Southeast Asia cities began building walls when they needed defence against the Europeans. Aytthaya built its walls in 1550 and Makassar erected fortifications in 1634 to protect itself from Dutch attack (Reid 1993: 88). Wittfogel's ideas of oriental despotism have been criticised (Hindess and Hirst 1975: 213) and Edward Said (1978) challenged Western conceptions about Asia in general as a social construction of the Orient.

Following the legacy of European classics, Asian cities were studied using Western theories and analysed as colonial, modernising and developing Third World cities. Studies of colonial Singapore (Yeoh 1996) analysed the land-use planning system brought by British colonial administrators. Studies of modern Singapore focused on the consequences of modernisation, industrialisation and urbanisation on culture and social institutions (Khondker 2002: 35). The development studies perspective was popular in Singapore, and until the 1980s much of the social s...