eBook - ePub

Sex

Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity

Alastair J. L. Blanshard

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

Sex

Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity

Alastair J. L. Blanshard

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity examines the impact that sexual fantasies about the classical world have had on modern Western culture.

- Offers a wealth of information on sex in the Greek and Roman world

- Correlates the study of classical sexuality with modern Western cultures

- Identifies key influential themes in the evolution of erotic discourse from antiquity to modernity

- Presents a serious and thought-provoking topic with great accessibility

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es Sex un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a Sex de Alastair J. L. Blanshard en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Letteratura y Critica letteraria antica e classica. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part I

Roman Vice

1

Introduction

In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, a number of still-shocked Manhattan inhabitants attempted to escape the horrors that haunted them through recourse to fantasy. For one night, a ‘sprawling loft in the Garment District’ became ancient Rome as Palagia, the self-proclaimed ‘queen of tasteful debauchery’ held Caligula’s Ball, an invitation-only orgy (Corrin and Moore 2002). The guests, all professional and under 40, dressed in sheer chiffon togas and indulged in threesomes, foursomes, wife-swapping, and light bondage. There was even a floorshow in which Palagia, surrounded by male assistants dressed as Roman legionaries, demonstrated the use of various sex toys and rode a tall, black, leather bench called ‘Caligula’s Horse’, after Incitatus, the horse made a senator by Caligula. Later Palagia was replaced by two performers called ‘Caligula’ and ‘Drusilla’ (the name of Caligula’s sister with whom he supposedly had an incestuous affair) who proceeded to give a demonstration of various positions of lovemaking.

Caligula’s Ball has been diagnosed as part of the phenomenon known as ‘terror sex’ – hard, casual, non-procreative sex as an alternative response to the threat of devastation. As one sex therapist put it, ‘party all night because you don’t know when the party is going to end’. Another located its origins in a primeval urge for survival and companionship, ‘in times of upheaval and terror, people look for confirmation of life, and there’s no more obvious antidote to death than sex. It’s a way of saying: “I’ m functioning, I’ m alive and I’m not alone”.’ Moments of crisis show us at our most instinctual. When people needed to imagine pleasure at its most decadent and debauched, their reflex was to reach out to Rome.

Rome has been described as a ‘pornotopia’ (Nisbet 2009: 150), ‘an ideal setting for the activities described in pornographic literature’ (OED), and even the most cursory survey of catalogs of pornographic film titles will reveal no end of classically themed erotica. Thus, films such as Private Gladiator Parts 1–3 (2001–2) compete with Roma (2007, ‘Ambition, Power, Lust, a thrilling trilogy’) and Serenity’s Roman Orgy (2001, ‘Let the games begin’) for the straight market; and for the gay market, there are titles such as Caligula and his Boys or Mansize – Marc Anthony (2003). The latter film won a pornographic film award for ‘Best Supporting Actor’ (FICEB 2003) and was nominated in the categories of ‘Best Art Direction’ and ‘Best Sex Comedy’ (2004 GAYVN Awards). The blurb on the back of the DVD gives a good indication of the film’s contents. It promises a world of imperial decadence and lust. Egypt is falling apart and the only way that Queen Cleopatra can restore peace to the kingdom is through marriage to the Roman general Marc Anthony. Unfortunately for poor Cleopatra, Marc Anthony turns out to be gay and there then ensues a homosexual romp through the Egyptian court. The queen is left frustrated, but the eunuchs seem to have enjoyed themselves.

Mansize – Marc Anthony follows in a long tradition of locating cinematic gay sex in Roman dress. For example, in the 1950s and 60s, physique movie mogul Richard Fontaine produced short black and white films such as Ben Hurry (c.1960) and The Captives (c.1959). These films are typical of the soft-porn gay films produced between the 1940s and 60s by film companies such as Apollo and Zenith. In Ben Hurry (the name is a play on ‘Ben Hur’) muscled men in Roman-style costumes and posing pouches strike poses and feel each other up. The conceit of the film is that these men are extras on the filming of Ben Hur. At the end, before anything too explicit can happen, the men are called back onto set; the shout of ‘Ben Hurry’ giving the title of the film. In contrast, The Captives is set in Rome itself and features a Roman official who inflicts homoerotic tortures on two men accused of spying. Eventually their refusal to talk and their obvious devotion to each other cause the official to free them. Stills from the film show athletic models with buff bodies, sporting the skimpiest of Roman-style kilts.

Yet we don’t need X-rated films to confirm Rome’s status as a ‘pornotopia’. Any visit to Pompeii will show you that when tourists think Rome, they think sex. Pompeii has many attractions, but the one that is on every visitor’s list is the brothel. If you haven’t been to the brothel, then you haven’t visited Pompeii. Its reopening to the public in 2006 was trumpeted around the world. Fascination with the brothel has existed ever since it was first excavated in 1862. Mark Twain describes his visit there, mentioning that ‘it was the only building in Pompeii in which no woman is allowed to enter’ and that the pictures ‘no pen could have the hardihood to describe’ (Twain 1869: 247). In their study of tourists’ attitudes to Pompeii’s brothel, Fisher and Langlands (2009) discuss the way in which the guides’ and tourists’ own preconceptions about Rome combine to create a notion of Pompeii as a place free from sexual repression and bodily hang-ups. Often this construction has an element of wish fulfillment as Pompeii ‘is used as a stick to beat contemporary moral conservatism’ (180). Confirming the notion of the centrality of the brothel to the life of this town is the re-conceptualization of the various phalloi dotted around the city as ‘signs pointing the way to the brothel’. This fantasy about the function of these phallic markers, perpetuated by numerous modern tour guides, extends, at least, as far back as the start of the nineteenth century. Everywhere the tourist wanders in Pompeii, they seem to be directed back to a brothel.

In this section, I want to examine how Rome’s status as a ‘pornotopia’ was achieved. It is easy to see this eroticization of Rome as the perpetuation of a Christian technique that sought to denigrate pagan practice by associating it with sin, especially bodily sexual sin. Once attitudes to the body and sex became a marker that distinguished Christian from non-Christian, it was inevitable that stories of corrupt sex would be ascribed to opponents. In focusing so much on sex, Christians were following in a substantial tradition. Attitudes to sex had long been one of the ways by which religious groups had differentiated themselves from their neighbors. This discourse on the lasciviousness of ancient Rome in contrast to a chaste Christianity can be traced back at least as far as the second century AD.

This discourse has a tendency to reassert itself at times of crisis. Whenever kingdoms or empires feel threatened, moralizing discourse tends to increase. It is the flip-side of ‘terror sex’, an apotropaic invocation of lost virtue. A clear example is the anxiety felt in Britain about the potential fall of her empire. Here the parallels with Rome felt uncomfortably close and the stories about Roman depravity played to an audience worried about contemporary morals. Sexy Rome simultaneously horrified and tantalized audiences.

Yet, fantasies do not appear out of thin air. Rather, they are grafted onto pre-existent sturdy stock. They need a secure foundation for support and nourishment. Often the stuff of fantasy is not intrinsically or intentionally erotic. It is striking how often markers of seemingly sober, chaste authority are transformed into objects of sexual fetish. Sex shops, for example, do a roaring trade in eroticized versions of uniforms of firemen, nurses, and male and female police officers. Here the aura of respectable authority gives their sexualized counterparts a charge of illicit, subversive thrill. Power rarely operates straightforwardly and the eroticization of power and its accoutrements is one of western culture’s more distinctive features.

It is not just aesthetics that are co-opted for fantastic purposes. Fantasy constructs complex scenarios out of snatches of dialogue, poetic motifs, comic exaggeration, historical events, programmatic ideological dictates, and heartfelt shouts of protest. It extends, confounds, inverts, stylizes, and stereotypes this material. Yet always at its heart exists a grain of the non-fantastic, a trace of a place that is prior to the fantasy.

In the following discussion, I want to highlight the aspects of Roman antiquity that helped secure it as the locus of the West’s sexual fantasies. Roman attitudes towards bodily display, its frank discussion of sex especially within genres of vituperative exchange, its occasional, but nevertheless marked collocations of sex and religious practice, and finally its gossip culture and the stories it told about emperors, all helped fuel erotic discourse. By looking at each of these elements in turn, I want to catalog the features that made Roman antiquity such an efficient vehicle for the expression of desire.

Each section begins with a pivotal moment or important case study that helps to articulate the themes that I want to pursue in the discussion. In keeping with the focus on unmediated reception, these case studies are often juxtaposed with the classical material that proves their inspiration. Throughout the discussion of these elements, the aim remains the elucidation of the narrative function of the material within the context of a history of ideas. I want to strip the classical material down to its essence to see what features have proved most productive in the formulation of sexual fantasy. Often these aspects are best revealed by analyzing a classical motif through a series of genres or receptions, each moment helping to reveal the reason for the efficacy of the motif in furthering sexual discourse.

2

Naked Bodies

An Introduction (less than successful) to the Naked Body

In 1832 to commemorate the centenary of Washington’s birth, Congress commissioned the American sculptor Horatio Greenough (1805–1852) to execute a statue of George Washington to be displayed in the Capitol Rotunda. In many ways, it was an unremarkable commission. Greenough had established himself, along with Hiram Powers (1805–1873) and Thomas Crawford (c.1813–1857), as one of the leaders of an important new generation of American sculptors. It was a generation that sought to combine a European, specifically Italian, tradition in sculpture with a sensibility drawn from the New World. Previous commissions for public figures such as his busts of Josiah Quincy Jr., the mayor of Boston (1827) and John Quincy Adams (1828) had been well received. Whilst working on the sculpture of Washington, Greenough also produced allegorical sculptures such as Child and Angel (1833) and Love Prisoner to Wisdom (1834), which in their use of children as symbols of innocence and purity showed that Greenough had a deft hand in conveying the sentimental morality so popular with large sections of the American audience.

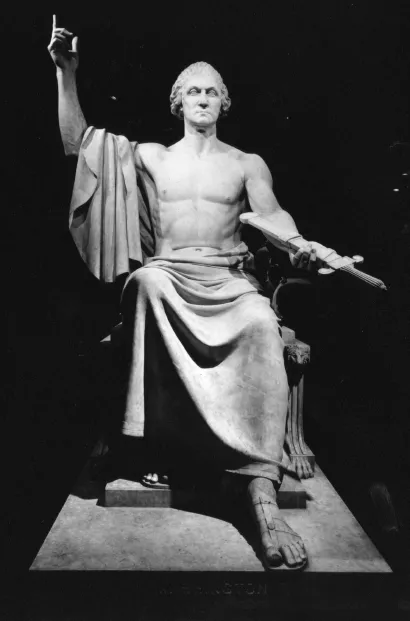

Few were expecting the furor that would erupt on the unveiling of the statue of Washington in 1841 (see Figure 2.1). The statue depicts Washington bare-breasted seated on an antique throne decorated with garlands and carved relief panels. His form of dress is antique, although he wears his customary eighteenth-century wig. The face was modeled on Jean-Antoine Houdon’s famous terracotta bust (1785) of the revolutionary leader. However, the body with its firm, defined, idealized musculature clearly looks to classical sculpture. In his left hand, Washington holds out a sheathed sword, a sign of peace and the end of conflict. His right arm is raised, and a finger points to the sky. His left foot is forward while the right rests on a footstool.

Figure 2.1 Horatio Greenough, George Washington (1840). An immodest president. Greenough’s statue has found few admirers. Smithsonian American Art Museum, transfer from the U.S. Capitol.

Reaction to the statue was almost universally negative. Some found the image too authoritarian. Like many others at the time, Greenough had taken a great interest in the reconstruction of Phidias’ Olympian Zeus published in Quatremère de Quincy’s Le Jupiter Olympien (1815). Greenough’s statue in pose and iconography clearly imitates the reconstruction. In portraying Washington as the ruler of the gods, Greenough flirted with iconography that did not play due deference to the democratic ideology of the new republic. The combination of throne and footstool (suppedaneum) was reserved mainly for divine or imperial personages in classical art. Greenough’s statue hinted at a system of values that failed to accord with the egalitarian nature of American politics. Congressman Smith from Alabama thought that such art might be weakening to the American constitution. Why, he wondered, were experiments in republican government always so short-lived and unsuccessful in Europe? The answer lay in art. How could a republic survive when it was surrounded by ‘antiquities and monuments, breathing, smacking and smelling of nobility and royalty’ (Greenough 1852: 17)? Yet as Daniel Chester French demonstrated 73 years later with his much-loved statue of Lincoln (1914–20, dedicated 1922) it was entirely possible for the Lincoln Memorial to square such iconography with the popular democratic mindset. If anything, his statue of Lincoln imitates Phidias’ statue even more closely than Greenough’s example.

Others thought the statue’s classicism too European and not fitting for an American subject. The status of classicism in American public art had been debated ever since the founding fathers. Thomas Jefferson was a strong admirer of classical aesthetics while George Washington was less certain about ‘a servile adherence to the garb of antiquity’. Davy Crockett (1786–1836) seemed to speak for many when he remarked on another neo-classical statue of Washington (1826) by Sir Francis Chantrey, ‘I do not like the statue of Washington in the State House. They have a Roman gown on him and he was an American; that ain’t right. They did a better thing at Richmond in Virginia where they have him in the old blue and buff. He belonged to his country – heart, soul, and body and I don’t want any other country to have part of him – not even his clothes’ (Crawford 1979: 42). Yet, as Crockett’s criticism indicates, neo-classical statues of George Washington were hardly new or surprising. The very first commission for an equestrian statue of Washington requested that he appear ‘in Roman dress, holding a truncheon in his right hand’. In addition to the statue by Chantrey, one could add the neoclassical statue of Washington (1817–21) by Antonio Canova. This statue, which was commissioned by the legislature of North Carolina, depicted Washington as a Roman general in sandals and cuirass who has put down his sword and picked up his pen to begin his legislative program. It was erected in the senate house in Raleigh, Durham in 1821, but unfortunately was destroyed by fire ten years later. Only a plaster model survives, but it clearly shows Washington as the most Roman-looking of figures (as indeed had been specified in the commission) as ...