eBook - ePub

A New Introduction to Islam

Daniel W. Brown

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

A New Introduction to Islam

Daniel W. Brown

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

Covering the origins, key features, and legacy of the Islamic tradition, the third edition of A New Introduction to Islam includes new material on Islam in the 21st century and discussions of the impact of historical ideas, literature, and movements on contemporary trends.

- Includes updated and rewritten chapters on the Qur'an and hadith literature that covers important new academic research

- Compares the practice of Islam in different Islamic countries, as well as acknowledging the differences within Islam as practiced in Europe

- Features study questions for each chapter and more illustrative material, charts, and excerpts from primary sources

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es A New Introduction to Islam un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a A New Introduction to Islam de Daniel W. Brown en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Theology & Religion y Islamic Theology. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

Part One

The Formation of the Islamic Tradition

1

Islam in Global Perspective

The Problem of Defining Islam

If we were to draw a circle and designate the contents of that circle as the complete set of phenomena that fall under the rubric of Islam, how would we decide what would be included within the circle and what must be excluded? Provocative examples are easy to find. Do the actions and motivations of those who fight for the self-designated Islamic State in Syria and northern Iraq or those who destroyed New York's World Trade Center or the London Underground bombers fall within the circle of Islam? Or should “true” Muslims abhor and repudiate such actions? The problem is not limited to the question of violence, of course. Does the rigorous constraint of women's rights by IS, the Taliban of Afghanistan, or the present regime of Saudi Arabia belong in the circle? If so, how can the ideas of Muslim feminists like Amina Wadud or Fatima Mernissi also fit alongside them? When Elijah Muhammad, twentieth-century Prophet of the Nation of Islam asserted that the white man is the devil and the black man God, was he representing Islam? Reaching back into Islamic history we can multiply the examples. Do the doctrines of Shiʿite Muslims who taught that ʿAli was an incarnation of God fall within the circle of Islam? What of the speculations of the Islamic philosophers who held that the universe is eternal and treated revelation as little more than philosophy for the masses? Were the targeted assassinations of the Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs “Islamic”? What of the modern Aḥmadiyya movement, rejected as heretical by many Muslims, but whose members insist they represent the true expression of Islam?

This exercise quickly exposes a common confusion. For the believing Muslim the question is meaningful. It is essential for the believer to determine where the boundaries of his faith community lie and to decide what represents Islam and what does not. But for those, whether believers or not, who seek to understand Islam as a movement of people and ideas in history, this way of thinking will not do. Whether we take an anthropological, historical, or religious studies perspective, all of the phenomena I have listed belong within the realm of the study of Islam.

And this raises a further problem that is central to any attempt to offer an overview of a major religious tradition. If such conflicting movements of people and ideas all belong in the circle of Islam, how is one to go about introducing the whole lot of them? How is it possible to “introduce” such a diverse, indeed contradictory, set of phenomena? One common answer is that the attempt is in itself misleading and fruitless; the idea of “Islam” with an upper-case “I” is a false construct; we should rather speak of many different lower-case “islams” which must be examined as separate phenomena. To paraphrase a political maxim, all religion is local, and to imagine that all these different “islams” have something in common which can be labeled “Islam” is to imagine something that has no reality. Since I have already written several hundreds of pages in which I have tried to introduce Islam with an upper-case “I,” it is too late for me to take this perspective. Nor am I inclined to do so.

My own perspective is best introduced by analogy. When a student sets out to study a language, Arabic for instance, she will soon learn that there are many quite different varieties of Arabic. Yet she will not normally trouble herself with the question of whether such different linguistic phenomena deserve to be called “Arabic.” And she is quite right not to be troubled. Arab grammatical police might worry about demarcating the precise boundaries of true “Arabic,” but from a common-sense perspective it is clear that all of the different dialects and varieties of the Arabic language rightly share the family name. Even if speakers of Moroccan and Palestinian Arabic may sometimes have some difficulty communicating, they all belong within the circle of Arabic speakers. In particular, the dialects they speak share sufficient common roots, sufficient common vocabulary, or a close enough grammatical structure to make it clear that they belong to the same family. It would be perfectly reasonable for a linguist to set out to survey the common structures, lexicon, and heritage of the whole family of dialects that are called Arabic, and so to introduce Arabic.

This analogy may help in another way. A linguist who sets out to write a descriptive survey of a family of dialects is doing something quite different from the language instructor whose job it is to teach a “standard” form of the language. While the goal of the language instructor is to help the student to become immersed in and to actually use the language, the academic linguist has no such ambition or expectation. In a similar way, I have little expectation that a book like this will be much help to anyone who comes to it hoping to find help in becoming a practicing Muslim.

It is in that spirit that I have set out to introduce Islam here, and this book might be seen as an attempt to explain the evolution of the common grammar and vocabulary of Islam. Thus the Islamic feminist and the Taliban both belong here, for although they are diametrically opposed in their conclusions, they make use of a common vocabulary and reference a common heritage. Similarly the Muslim pacifist and the suicide bomber, the Nizārī “assassin” and the Sunni religious scholar who condemns him, are responding, albeit in very different ways, to a shared tradition. Indeed, they are contending for control of that tradition.

Mapping the Islamic World

Clearly the set of phenomena to which we apply the label “Islam” is exceedingly varied, and there is enough complexity in the literatures, histories, philosophies, theologies, rituals, and politics of Islamic civilization to engage many lifetimes of study. Oversimplifying will not do. But keeping that danger in mind, we can still attempt to gain some sense of the big picture before our attention is consumed by details. There is a place for the global view that excludes most detail just as there is for the street-level view that includes it all.

A map turns out to be a useful starting point. If we peruse a map of the contemporary Islamic world, what will we notice? We can begin with a simple demographic survey. Map 1 is a graphic depiction of the world's Muslim population by country. The first thing to notice about this map is that it includes the entire world. The time when we could depict the Muslim world on a single hemisphere is long past, although many cartographers have yet to catch on. The contemporary Muslim community, the umma, is worldwide. Muslims live, work, raise families, and pray everywhere, from China to California, from Chile to Canada; there is almost no place on earth where Muslims have not settled. This simple fact turns out to be both easily forgotten and immensely important to understanding contemporary Islam. The modern Muslim diaspora is shaping the course of Islam, and of the world. Many critical issues facing contemporary Muslims arise precisely because so many influential Muslims are German, French, British, Canadian, Dutch, or Australian. Muslims work throughout the world as scientists and scholars, teachers and doctors, lawyers and entrepreneurs, farmers and factory workers. Their responses to this geographical mobility and the pluralism of the varied societies in which they live fuel rapid change in Muslim communities, and significant conflict among Muslims as well as between some Muslims and their non-Muslim neighbors. The experience of Muslims as a truly worldwide community has stimulated new and pressing discussions of the relation of Islam to women's rights, human rights, bioethics, religious diversity, tolerance, and freedom of expression.

Controversies over cartoon depictions of Muhammad are a case in point. In 2006 the Danish newspaper al-Jostens published cartoon images of Muhammad. Muslim reaction, sometimes violent, led to wide scale republication of the images in the name of freedom of expression. In the following decade similar controversies followed a similar pattern, culminating most recently in 2015 with the deadly attacks on the Paris offices of Charlie Hebdo. The publication of the al-Jostens and Charlie Hebdo cartoons, and the varied Muslim responses, were a product of a Muslim community that spans the globe. The cartoons were published in the first place because the Muslim community in Europe is sizeable enough to motivate fierce debate about the compatibility of Islam with European cultural and political tradition. Authors like the pseudonymous Ba't Yeor raise the specter of “Eurabia,” a Europe held hostage to Islamic radicalism because Europeans have failed to recognize the threat to freedom and to European tradition posed by Islam. The Muslim response to the cartoons was worldwide, however, and often the fiercest reactions come from outside of Europe.

Map 1 Distribution of Muslim population by country

Muslims are concentrated in Asia, but significant numbers of Muslims now live on every continent. This map should be read with caution, however. Russia, for example, has a population of more than 14 million Muslims, but this population is not evenly distributed throughout its vast territory as the map seems to suggest, nor does Alaska have significant numbers of Muslims. China has a large Muslim population, but there is a great deal of uncertainty about its actual size. Population figures used for this map were drawn from the database at adherents.com.

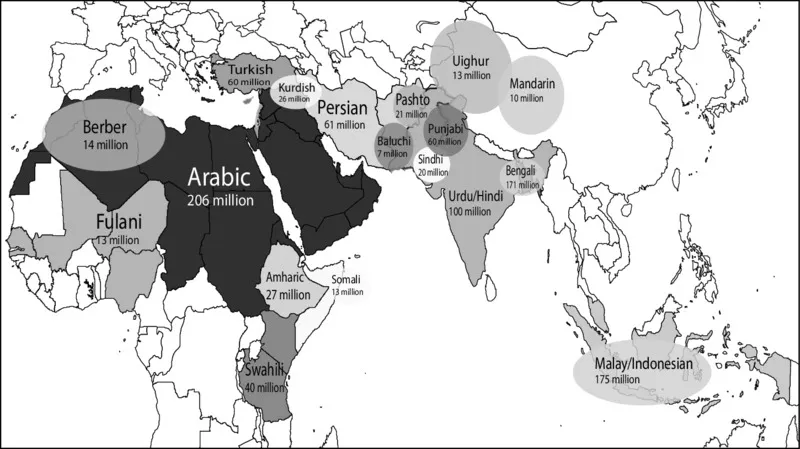

Map 2 Major languages spoken by Muslims

The map shows something of the linguistic diversity of the Muslim world. For a catalogue of all of the hundreds of languages spoken by Muslims, see the source from which the data for this map was drawn, Raymond G. Gordon, Jr., ed., 2005. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 15th edn. Dallas, TX: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com/.

But while Islam is worldwide, our map also gives rise to a second, paradoxical observation: Muslims are heavily concentrated in Asia and Africa. More than 50 percent of the world's Muslims live in just eight countries: Indonesia, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Nigeria, Iran, Turkey, and Egypt. This list is surprising for two reasons. First, the majority population of only one of these, Egypt, is Arabic speaking. The range of cultures and languages for which the most populous Muslim countries are home is staggering. More than twice as many Muslims speak Indonesian, Bengali, or Urdu as speak Arabic. Map 2, portraying the major languages spoken by Muslims, hints at this cultural and linguistic diversity but also grossly understates it by leaving out hundreds of smaller languages.

The second surprise is that a great many contemporary Muslims live in religiously plural societies. In India, Muslims are, despite their numbers, dwarfed by the size of the majority population. China, with 40 million or more Musl...