eBook - ePub

A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE

Jonathan M. Hall

This is a test

Compartir libro

- English

- ePUB (apto para móviles)

- Disponible en iOS y Android

eBook - ePub

A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE

Jonathan M. Hall

Detalles del libro

Vista previa del libro

Índice

Citas

Información del libro

A History of the Archaic Greek World offers a theme-based approach to the development of the Greek world in the years 1200-479 BCE.

- Updated and extended in this edition to include two new sections, expanded geographical coverage, a guide to electronic resources, and more illustrations

- Takes a critical and analytical look at evidence about the history of the archaic Greek World

- Involves the reader in the practice of history by questioning and reevaluating conventional beliefs

- Casts new light on traditional themes such as the rise of the city-state, citizen militias, and the origins of egalitarianism

- Provides a wealth of archaeological evidence, in a number of different specialties, including ceramics, architecture, and mortuary studies

Preguntas frecuentes

¿Cómo cancelo mi suscripción?

¿Cómo descargo los libros?

Por el momento, todos nuestros libros ePub adaptables a dispositivos móviles se pueden descargar a través de la aplicación. La mayor parte de nuestros PDF también se puede descargar y ya estamos trabajando para que el resto también sea descargable. Obtén más información aquí.

¿En qué se diferencian los planes de precios?

Ambos planes te permiten acceder por completo a la biblioteca y a todas las funciones de Perlego. Las únicas diferencias son el precio y el período de suscripción: con el plan anual ahorrarás en torno a un 30 % en comparación con 12 meses de un plan mensual.

¿Qué es Perlego?

Somos un servicio de suscripción de libros de texto en línea que te permite acceder a toda una biblioteca en línea por menos de lo que cuesta un libro al mes. Con más de un millón de libros sobre más de 1000 categorías, ¡tenemos todo lo que necesitas! Obtén más información aquí.

¿Perlego ofrece la función de texto a voz?

Busca el símbolo de lectura en voz alta en tu próximo libro para ver si puedes escucharlo. La herramienta de lectura en voz alta lee el texto en voz alta por ti, resaltando el texto a medida que se lee. Puedes pausarla, acelerarla y ralentizarla. Obtén más información aquí.

¿Es A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE un PDF/ePUB en línea?

Sí, puedes acceder a A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE de Jonathan M. Hall en formato PDF o ePUB, así como a otros libros populares de Historia y Historia de la antigua Grecia. Tenemos más de un millón de libros disponibles en nuestro catálogo para que explores.

Información

1

The Practice of History

The Lelantine War

To the modern visitor the Lelantine plain might seem an unlikely setting for a conflict of epic dimensions. Flanking the southern coast of the island of Euboea, just across from the mainland regions of Attica and Boeotia, the plain is today dotted with holiday villas and summer homes as well as the odd physical remnant of the area's earlier importance for the brick-making industry, but its economy – now, as in antiquity – is dominated by the cultivation of cereals, olives, figs, and vines. The ancient cities of Chalcis and Eretria, like their modern namesakes, lay at either end of the plain, twenty-four kilometers apart. Relations between the two were initially cordial enough: according to Strabo (5.4.9), Pithecusae, on the Italian island of Ischia, was a joint foundation of Eretrians and Chalcidians, probably in the second quarter of the eighth century. But both cities had expanding populations that they needed to feed and in the final decades of the eighth century the two came to blows over possession of the plain that lay between them.

The aristocrats of Euboea were renowned for their horsemanship and for their skill with the spear. Both Aristotle (Pol. 4.3.2) and Plutarch (Mor. 760e–761b) refer to cavalry engagements, but the Archaic poet Archilochus (fr. 3) implies that the warriors also fought on foot and at close quarters with swords, rather than relying upon slings and bows. Indeed, Strabo (10.1.12) claims to have seen an inscription, set up in the sanctuary of Artemis at Amarynthos (eight kilometers east of Eretria), which recorded the original decision to ban the use of long-range weapons such as slings, bows, or javelins. It was a war, then, conducted according to a chivalric code we normally attribute to medieval knights.

Those who sacrificed their lives for their cities were treated like heroes. Around 720, an anonymous Eretrian warrior was accorded funerary honors that parallel closely the Homeric description of Patroclus' funeral in the Iliad. The warrior's ashes had been wrapped in a cloth along with jewelry and a gold and serpentine scarab, then placed in a bronze cauldron, covered by a larger bronze vessel, and buried on the western perimeter of the settlement, next to the road that led to Chalcis. With the cinerary urn were buried swords and spearheads, which denoted the deceased's martial prowess, and a bronze staff or “scepter,” dating to the Late Bronze Age, whose antique status probably served to express the authority he had formerly held in his home community. Charred bones indicate that animals – including a horse, to judge from an equine tooth – were sacrificed at the site of the grave, probably on the occasion of the funeral. Over the next generation, six further cremations of adults (presumably members of the same family) were placed in an arc around the first, while slightly to the west were situated the inhumation burials of youths, arranged in two parallel rows. In both cases, the funerary rites differ from those that were then in vogue in the city's main necropolis by the sea. In the Harbor Cemetery, the corpses of infants had been stuffed into pots whereas at the West Gate they had been afforded the more dignified facility of a pit grave, accompanied by toys and miniature vases, and whereas adults in the Harbor Cemetery were also cremated, their ashes were not placed in cinerary urns nor were their burials accompanied by costly grave goods. After the last burial, ca. 680, a triangular limestone monument was constructed above the cremation burials and from the deposits of ash, carbonized wood, animal bones, drinking cups, and figurines found in the immediate vicinity, we can assume that ritual meals continued to take place in honor of the dead here until the fifth century.

Chalcis had its war heroes too. The poet Hesiod (WD 654–5) recounts how he had once crossed over from Boeotia to Chalcis to attend the funeral contests held in honor of “wise” Amphidamas and won a tripod for a song he had composed. Plutarch (Mor. 153f) adds that many famous poets attended these funerary games and that Amphidamas “inflicted many ills upon the Eretrians and fell in the battles for the Lelantine plain.” Elsewhere (760e–761b), he tells of horsemen from Thessaly, the great upland plain of northern-central Greece, who had been summoned by the Chalcidians, fearful of the Eretrian cavalry's superiority. Their general, Kleomakhos, was killed in the fighting and was granted the signal honor of being buried in the agora of Chalcis, his tomb marked by a tall pillar.

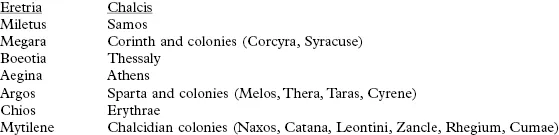

The war was no purely local affair. According to Thucydides (1.15), the entire Greek world was divided in alliance with one or other of the two protagonists in a collective effort that would not be seen again until the great wars of the fifth century (Figure 1.1). Herodotus (5.99) mentions a war between Eretria and Chalcis in which Miletus, the most important Ionian foundation on the coast of Asia Minor, had taken the side of Eretria and Miletos' island neighbor, Samos, that of Chalcis. Other allies can only be assigned to sides on evidence that is more circumstantial. Given that Corinthian settlers are supposed to have expelled Eretrians from Corcyra (the modern island of Corfu) in 733 (Plutarch, Mor. 293b), that Megarian colonists are said to have been driven out of Sicilian Leontini by Chalcidians five years later (Thucydides 6.4), and that the hostility between Corinth and its neighbor, Megara, was proverbial, one can assume that Megara was allied with Eretria and Corinth with Chalcis. Thessaly, as we have seen, came to the aid of Chalcis, which might suggest that Thessaly's neighbor and enemy, Boeotia, was on the side of Eretria, along with the island of Aegina, which claimed a special relationship with Boeotia (Herodotus 5.80) and had itself engaged in hostilities with Samos (3.59). The Peloponnesian city of Argos, an ally of Aegina (5.86) and an enemy of Corinth, probably sided with Eretria while Argos' enemy Sparta, which had been assisted by Samos during the Messenian War (3.47), would have favored Chalcis, as would Aegina's enemy Athens. Since Mytilene on the island of Lesbos contested control of the Hellespontine city of Sigeum with Athens (5.95), it is unlikely to have fought alongside Athens on the side of Chalcis, and Miletus' ancient alliance with the island of Chios against the Ionian city of Erythrae (1.18) may allow us to assign Chios to the Eretrian contingent and Erythrae to the Chalcidian. Finally, it is to be expected that “colonial” foundations would have taken the side of their mother-cities: thus Chalcis is likely to have been supported by her own colonies in the west (Naxos, Catana, Leontini, and Zancle on Sicily, Rhegium and Cumae on the Italian mainland), as well as by the Corinthian colonies of Corcyra and Syracuse and the Spartan colonies of Melos, Thera, Taras, and Cyrene.

Figure 1.1 The alliances that have been proposed for Eretria and Chalcis in the Lelantine War

History does not record the outcome of the conflict. It is possible that hostilities continued intermittently for some considerable time because Archilochus (fr. 3), conventionally assigned to the middle of the seventh century, appears to imply a resumption of combat in his own day while verses attributed to the Megarian poet Theognis (891–4) protest that “the fine vineyards of Lelanton are being shorn” and assign the blame to the descendants of Cypselus, who seized power at Corinth around the middle of the seventh century. There are, however, hints that Eretria fared worse than Chalcis. Firstly, the site of Lefkandi, which is situated on the coast between Chalcis and Eretria and had been a flourishing and wealthy community in the eleventh and tenth centuries, appears to have been destroyed around 700. Strabo (9.2.6) makes a distinction between an Old Eretria and a Modern Eretria, and given that Lefkandi begins to go into decline ca. 825 – that is, at about the same time that Eretria develops as a center of settlement – it has been argued that Lefkandi had been Old Eretria and that it was a casualty of Chalcidian action towards the end of the eighth century. Secondly, the cooperation between Eretria and Chalcis in overseas ventures came to an abrupt end in the last third of the eighth century. The Chalcidians who had settled Pithecusae are said to have transferred to the Italian mainland where they founded Cumae (Livy 8.22.6), but for the remainder of the century it is Chalcis rather than Eretria that continues to play a pivotal role in such western ventures. A Delphic oracle (Palatine Anthology 14.73), perhaps dating to the seventh century, lavishes praise on “the men who drink the water of holy Arethousa” (a spring near Chalcis) and the land that Athens confiscated from Chalcis in 506 bce lay in the Lelantine plain (Aelian, HM 6.1).

The foregoing sketch would appear to offer an impressive demonstration of how historians can assemble fragments of evidence from various literary authors and combine them with the findings of archaeologists to draw a vivid picture of past events – no mean achievement for a period in which literacy was still in its infancy and for which contemporary documentation is practically nonexistent. Unfortunately, this whole reconstruction is probably little more than a modern historian's fantasy, cobbled together from isolated pieces of information that, both singly and in combination, command little confidence.

The Lelantine War Deconstructed

To begin with, the authors whose notices are culled to generate this composite picture span a period of some nine centuries – roughly the same amount of time as from the Battle of Hastings to the present day. The poems of Hesiod, Archilochus, and Theognis probably date to the seventh century (though see below); Herodotus and Thucydides were writing in the later fifth century, Aristotle in the middle of the fourth, Livy towards the end of the first century, Strabo around the turn of the Common Era, Plutarch at the turn of the second century ce, and Aelian at the beginning of the third (see the Glossary of Literary Sources). The testimony of late authors is less weighty if they are merely deriving their information from that of the earlier authors we possess rather than from an independent tradition. While it is unlikely that Thucydides was reckless enough to base his belief in the universal “Panhellenic” nature of the war on Herodotus' notice that Miletus had once fought with Eretria against Chalcis and Samos, Plutarch's description of the poetic contests at the funeral of Amphidamas stands a good chance of representing an elaboration on the testimony of Hesiod, who never actually mentions the Lelantine War.

Nor is it likely that Thucydides invented out of thin air a tradition about widespread participation in a Lelantine War. He mentions this early war in order to justify his contention that the Peloponnesian War of 431–404 was the greatest upheaval to have ever affected the Greek world, notwithstanding the great military campaigns of the past. The Lelantine War stands in the same relationship to the Peloponnesian War as the Trojan War does to the Persian War: the former are wars among Greeks while the latter are wars between Greeks and their eastern neighbors, but in each set the more recent war is greater in scope than the former. Clearly, the rhetoric here could not have been effective unless Thucydides' readership was already familiar with a story in which Eretria and Chalcis had been joined by many allies in their war against each other. Yet the existence of a tradition that predates Thucydides does not guarantee its authenticity. It is surely not insignificant that none of our earlier literary sources implies a broader conflict. Furthermore, Thucydides compares the Lelantine War with the Trojan War and while some historians and archaeologists might be prepared to accept that a genuine Mycenaean raid on the Anatolian coast underlies the elaborated traditions about the Trojan War, few believe that the conflict was as epic or as global as myth and epic remembered. Why should the Lelantine War have been any different? In fact, the impressive roster of alliances hypothesized above is built on scattered notices about alliances and hostilities that were anything but contemporary: the Corinthian expulsion of Eretrians from Corcyra is supposed to have taken place in 733 but the alliance between Argos and Aegina dates to around 500, some seven generations later. Are we to believe that Greeks in the Archaic period were so consistent in their loyalties? And how seriously, in any case, should we take such notices? The Eretrian settlement on Corcyra is mentioned only by Plutarch and has, up to now, received absolutely no corroboration from archaeological investigations on the island.

Plutarch is also our only source for the intervention of Thessaly on the side of Chalcis. This testimony is not incompatible with Thucydides' picture of a broader conflict, but neither is it exactly an exhaustive endorsement of the grand alliances that he suggests. In fact, there is a good chance that Plutarch's information derives not from a tradition that was also known to Thucydides but from a story attached to a monument at Chalcis – namely, the column that supposedly marked the tomb of the Thessalian hero Kleomakhos in the agora. Whether or not the tomb really contained the remains of a warrior who fell in the Lelantine War is as unverifiable for us as it was for Plutarch. Monuments may create, as much as perpetuate, social memory.

Similarly, it is far from apparent that Herodotus, in his description of the alliance between Eretria and Miletus against Chalcis and Samos, has in mind the more global conflict recorded by Thucydides. The earlier alliance is mentioned in order to explain why the Eretrians joined the Athenians in providing support to the Ionians of East Greece on the occasion of the latter's revolt in 499: “they did not campaign with them out of any goodwill towards the Athenians but rather to pay back a debt owed to the Milesians, for the Milesians had earlier joined the Eretrians in waging the war against the Chalcidians, on exactly the same occasion as the Samians helped the Chalcidians against the Eretrians and Milesians” (5.99). The wording appears to leave little scope for the participation of additional combatants, but neither can we exclude the possibility that the earlier, undated alliance was invented to justify Eretrian intervention at the beginning of the fifth century. As for Aristotle, it is difficult to maintain that his reference to a cavalry war between Eretria and Chalcis is derived from Archilochus, whose mention of the use of swords clearly implies an infantry engagement. He could be following an independent source but it is more likely that he has made the inference on the basis of the names given to the elite classes at Eretria and Chalcis – the Hippeis (horsemen) and Hippobotai (horse-rearers) respectively. From there, the idea that the war had involved both cavalry and infantry could have passed to Plutarch, for whom Aristotle was often an important authority.

It might be thought that we are on firmer ground with those poets who are supposedly contemporary with the events they describe: Hesiod, Archilochus, and Theognis. Yet, here too we encounter difficulties. In most standard works of reference, Hesiod is dated to around 700, but how is this date derived? It relies in part on certain stylistic and thematic correspondences between the Hesiodic poems and the epics of Homer – though the dating of Homer and the relative chronological relationship between Homer and Hesiod are hotly contested by scholars (see pp. 23–4) – but it is also based on the assumption that Hesiod was a contemporary of the Lelantine War! Such circular reasoning cannot command much faith, especially since it is not Hesiod but Plutarch who associates Amphidamas with the Lelantine War. Archilochus is conventionally dated to the middle of the seventh century. One of his poems describes a total solar eclipse which is probably to be associated with that calculated as having occurred on April 6, 648, while one of his addressees, a certain Glaukos, son of Leptinos, is mentioned in a late seventh-century inscription found in the agora of Thasos, Archilochus' adopted home. Some literary scholars are, however, dubious that Archaic poetry can be read so autobiographically and consider such works to be the products of a cumulative synthesis of a city's poetic traditions which is continuously recreated over several generations and attached to the name of an original poet of almost heroic status. The fragmentary poems attributed to Archilochus were probably performed at the hero shrine established to the poet on his native island of Paros towards the end of the sixth century. Some elements of the oeuvre may well date back to the mid-seventh century but others could be a good deal later. This is even clearer in the case of the poetry ascribed to Theognis: the repetition of entire verses, the inclusion of couplets ascribed by other sources to poets such as Solon or Mimnermus, and the fact that some verses seem to refer to events of the seventh century while others allude to events that cannot predate the fifth century all give us reason to suspect that the Theognidea is more of a compendium of Archaic Greek poetry than the work of a single author.

There is a concrete quality to archaeological evidence that sometimes encourages us to believe that it can provide “scientific” confirmation or refutation of inferences made on the basis of literary texts. This is, unfortunately, a little optimistic. While it is essential that historians examine both the material and the literary records, the understandable urge to associate material items with textual correlates runs the risk of committing what Anthony Snodgrass has called the “positivist fallacy” – that is, of automatically equating what is archaeologically visible with what is historically significant. We need to remember that, just as only a tiny fraction of the texts that were known in antiquity has survived to the present day, so too the evidence that is studied by archaeologists represents only a minute proportion of the totality of human behavior in the past. The recovery of such material depends upon whether it was consciously or unconsciously disposed of at a particular moment in the past, whether it has been subject to degradation over several centuries or is instead imperishable, whether it has been located and retrieved by the archaeologist, and whether it has been correctly classified and identified, let alone interpreted. The burials that were subsequently honored by the West Gate at Eretria may be those of warriors who died defending their city in the Lelantine War, but they could just as easily be associated with the thousands of episodes of Eretrian history of which we know absolutely nothing.

A more particular consideration holds in the case of Lefkandi. The assumption that settlement at the site ceased ca. 700 is based on the original excavators' observation that a house, situated on the eastern slopes of the headland, was destroyed and abandoned towards the end of the Late Geometric pottery phase; further to the west, another structure seems to have been abandoned at the same time, though there are no indications there of a destruction. But since only a tiny proportion of the settlement at Lefkandi has been excavated and since sixth-century pottery has also been reported, even if its exact context is unclear, it is entirely possible that the so-called “destruction” of the site was merely a local conflagration and that other, unexcavated parts of the settlement continued to be occupied into the seventh century. Indeed, this is precisely what preliminary results of renewed investigation at the site of Lefkandi-Xeropolis, begun in 2003, now appear to suggest. Nor is it at all certain that Lefkandi should be identified with Strabo's Old Eretria. Elsewhere (10.1.10), the geographer seems to imply that Old Eretria was simply a quarter of Modern Eretria.

Finally, even if we were to take all this evidence at face value, there is a conspicuous lack of chronological synchronisms. The first warrior burial at the West Gate of Eretria dates to ca. 720, probably around two decades before the house at Lefkandi was destroyed. Archaeological dating is never, of course, precise and it is possible that the burial (and consequently the destruction) could be ten or fifteen years earlier – around the time, say, of the alleged expulsions of Eretrians from Corcyra and of Megarians from Chalcidian Leontini. The testimony of Hesiod could fit this early date – ...