Biological Sciences

Body Temperature Regulation

Body temperature regulation is the process by which the body maintains a stable internal temperature despite external fluctuations. This is achieved through a combination of physiological and behavioral mechanisms, such as shivering to generate heat or sweating to cool down. The hypothalamus in the brain plays a central role in coordinating these responses to ensure the body's temperature remains within a narrow range.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Body Temperature Regulation"

- Liana Bolis, Julio Licinio, Stefano Govoni(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

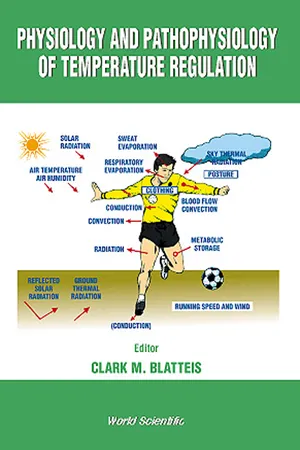

247 7 The Autonomic Nervous System and Thermoregulation Quentin J. Pittman University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada The thermoregulatory system is a controlled system requiring sensors, a con-troller, and effectors. Sensation of temperature occurs in the skin, deep body tis-sues, and within the central nervous system (CNS) through specialized thermore-ceptive fibers and neurons. Information about body temperature is integrated and compared to a reference temperature. This function is distributed in a number of CNS sites but is most highly concentrated in the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus utilizes endocrine, behavioral, and autonomic outputs to alter heat flow to the en-vironment and to alter heat production. These functions are mediated by sympa-thetic fibers to a number of end organs, including vascular smooth muscle, sweat glands, and brown adipose tissue, and by outputs to both respiratory and skeletal muscles. There is a close relationship between the thermoregulatory system and the control of metabolic rate for purposes of body weight regulation. Under envi-ronmental extremes or in the case of pathology, hypothermia or hyperthermia may result. These conditions, which represent a breakdown of normal thermoregula-tory control, are in contrast to fever, which is a regulated elevation of body tem-perature in response to cytokines and which is thought to be useful to the individ-ual in fighting disease. An additional possible beneficial effect of altered body temperature is in the case of controlled hypothermia as a treatment for ischemic brain injury. I. INTRODUCTION Our body temperature is precisely regulated. The stability of this regulation is widely appreciated; even those individuals not scientifically trained are usually aware that body temperature rests at approximately 37°C. Furthermore, deviations from this temperature have important diagnostic implications.- Clark M Blatteis(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

6 Physiology and Pathophysiology of Temperature Regulation In his concept of le milieur interieur, Claude Bernard placed the emphasis upon the protection furnished living cells by the nearly constant composition and temperature of the fluids which bathe them. "All the vital mechanisms, varied as they are, have only one subject, that of preserving constant the conditions of life in the internal environment. The fixity of the milieu supposes a perfection of the organism such that the external variations are at each instant compensated for and equilibrated. Therefore, far from being indifferent to the external world, the higher animal is on the contrary constrained in a close and masterful relation with it, of such fashion that its equilibrium results from a continuous and delicate compensation established as if by the most sensitive of balances. All of the vital mechanisms however varied they may be, have always but one goal, to maintain the uniformity of the conditions of life in the internal environment." (translated from the French) In the very simplified model of temperature regulation described here, of particular importance is what determines the actual body temperature and how is it controlled in man at around 37.5 °C. As in most physiological processes, a stimulus is received and a response is initiated. In temperature regulation, thermosensitive neurones that have thermosensitive receptors (nerve endings) and which are present in the periphery, in deep organs of the body and in the central nervous system, respond to changes in temperature. So called 'cold sensitive' neurones increase their firing rates as temperature falls, and 'heat sensitive' neurones increase their firing rates as temperature rises.- eBook - PDF

- James Kalat(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Cengage Learning EMEA(Publisher)

Copyright 2019 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. 289 Module 9.1 Temperature Regulation Homeostasis and Allostasis Controlling Body Temperature In Closing: Combining Physiological and Behavioral Mechanisms Module 9.2 Thirst Mechanisms of Water Regulation Osmotic Thirst Hypovolemic Thirst and Sodium-Specific Hunger In Closing: The Psychology and Biology of Thirst Module 9.3 Hunger Digestion and Food Selection Short- and Long-Term Regulation of Feeding Brain Mechanisms Eating Disorders In Closing: The Multiple Controls of Hunger Chapter 9 Internal Regulation Chapter Outline After studying this chapter, you should be able to: 1. List examples of how temperature regula-tion contributes to behaviors. 2. Explain why a constant high body tem-perature is worth all the energy it costs. 3. Describe why a moderate fever is advanta-geous in fighting an infection. 4. Distinguish between osmotic and hypovo-lemic thirst, including the brain mecha-nisms for each. 5. Describe the physiological factors that influence hunger and satiety. Learning Objectives Opposite: All life on Earth requires water, and animals drink it wherever they can find it. (© iStock.com/StockPhotoAstur) W hat is life? You could define life in many ways depending on whether your purpose is medical, legal, philosophical, or poetic. Biologically, the necessary condition for life is a coordinated set of chemical reactions. Not all chemical reactions are alive, but all life has well-regulated chemical reactions. - eBook - ePub

- F. Robert Brush, Seymour Levine(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER NINETemperature Regulation

Lawrence C.H. Wang and T.F. LeePublisher Summary

This chapter describes temperature regulation in organisms. The quest of achieving an optimal internal-thermal state to maximize biochemical efficiency encompasses both behavioral and autonomic efforts. Although superficially divergent in an internal-thermal state among the vertebrates, both ectotherms and endotherms share many common neural elements in sensing, deciphering, and responding to environmental thermal challenges. In the endotherms, autonomic capabilities allow the maintenance of a relatively constant internal-thermal state independent of environmental fluctuations. Neuroendocrine regulation of hibernation represents an important adaptive strategy for energy conservation under adverse conditions in many birds and mammals Changes in electrophysiological properties of an organism elicited by temperature are typically consequent of ionic or metabolic alterations, including changes in electrogenic sodium-pump activity and passive ionic permeability. This provides a neurophysiological basis for the warm sensation experienced by humans following intravenous calcium administration.I Introduction

The optimization of an internal thermal state for maximizing biochemical efficiency is of obvious survival value to organisms. In ectotherms (poikilotherms), the selection of a preferred thermal environment is accomplished mainly by behavioral means, whereas in endotherms (homeotherms), the maintenance of a relatively constant internal thermal state requires both behavioral and autonomic measures. Although they appear superficially divergent, both ectotherms and endotherms share many common neural elements governing thermoregulation; for instance, temperature transducers for the detection of ambient and internal thermal states, integrators or comparators for deciphering whether or not the internal thermal state is optimal, controllers for the activation or the inhibition of specific behavioral or autonomic measures, and effectors to carry out specific thermoregulatory tasks. To appreciate fully the neuroendocrine modulation of thermoregulatory functions, especially among the endotherms, it is perhaps beneficial to first have a firm grasp on the functional aspects of the individual neural elements followed by an understanding of their regulation by the neuroendocrine influences. Due to space constraint, only the most relevant points will be included, but recent reviews on specific topics will be listed wherever appropriate. Thermoregulation under modified physiological states, e.g., sleep, fever, and hibernation, will also be included to reflect species adaptations. An emphasis has been placed on neuroendocrine regulation of hibernation, not only because it represents an important adaptive strategy for energy conservation under adverse conditions in many birds and mammals, but also because it epitomizes the biochemical and physiological versatilities evolution is capable of amplifying to an existing thermoregulatory function. - eBook - PDF

Systemic Homeostasis And Poikilostasis In Sleep: Is Rem Sleep A Physiological Paradox?

Is REM Sleep a Physiological Paradox?

- Pier Luigi Parmeggiani(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- ICP(Publisher)

Chapter 5 Temperature Regulation in Sleep The control of body temperature is the clearest example of homeostatic regulation in mammals. The underlying mechanisms are complex, consisting of activity in several physiological functions, somatic and autonomic, both under the integrative control of the central nervous system. In this chapter, body temperature will be first considered in general. Then, the contribution to thermoregulation in sleep of the motor and postural activity of skeletal muscles, circulation and respiration will be examined from the viewpoint of homeothermy. These functions underlie the thermoregulatory responses that fit well within the temporal dimen-sions of the ultradian sleep cycle of NREM and REM sleep. Body Temperature Body temperature is a physical signal of both general physicochemical and specific physiological significance. In other words, body temperature influ-ences directly the cellular life (thermophysical and thermochemical effects) and indirectly the somatic and autonomic activity of the whole organism by excitation of specific thermoreceptors. As a result of the latter influence, thermoregulatory mechanisms maintain a substantial homeothermy of the body core in mammals. In homeothermic conditions, temperature, as a physical signal, sta-bilises the physicochemical processes in the body tissues notwithstanding the changes in ambient temperature. The fact that thermoregulatory responses are present or absent depending on the sleep state stresses the operative difference between the general and continuous non-specific action of the physical signal and its sleep state-dependent specific action as a physiological parameter that modulates feedback neural activity for 39 thermoregulation. In the latter case, the peripheral and central thermore-ceptors of the organism are influenced differently by temperature as a consequence of its thermal compartmentalisation in the shell and the core of the body. - eBook - PDF

- Stephan A. Mayer, Daniel I. Sessler, Stephan A. Mayer, Daniel I. Sessler(Authors)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Sessler 2 REVIEW Thermoregulation Body temperature is among the best regulated physiological parameters, rarely deviating by more than a few tenths of a degree Celsius. It is better regulated, e.g., than either heart rate or blood pressure. Core temperature deviations of even a couple of degrees Celsius in either direction are associated with complications (4–8). However, known complications fail to explain why mammals expend considerable effort to regulate temperature to within a few tenths of a degree. For example, it is not obvious why the body would regulate core temperature to a precision of tenths of degree when the normal circadian temperature approaches 1jC (15,16). However, similarly precise control is maintained in most species. It thus seems logical to assume that core temperature is well controlled for compelling physiological reasons—even if the reasons are not yet apparent. Afferent Input There are temperature-sensitive cells throughout the body, including the skin surface. Cold-sensitive cells increase their firing rate as they cool, whereas warm-sensitive cell do the opposite. Both are phenomenally sensitive. Human skin, e.g., can detect temperature changes of as little as a few thou- sandths of a degree Celsius (17). Cold signals travel primarily via AB nerve fibers and warm information by unmyelinated C fibers, although there is some overlap (18). The C fibers also detect and convey pain sensation, which is why intense heat cannot be distinguished from sharp pain. Most ascending thermal information tra- verses the spinothalamic tracts in the anterior spinal cord. With the exception of the skin surface (19), relative importance of thermal input from various regions of the body is difficult or impossible to determine. - eBook - PDF

Minder Brain, The: How Your Brain Keeps You Alive, Protects You From Danger, And Ensures That You Reproduce

How Your Brain Keeps You Alive, Protects You from Danger, and Ensures that You Reproduce

- Joe Herbert(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

Eds. E Schonbaum, P Lomax, pp. 53–183. ( Pergamon Press, New York) A homeostatic regulation implies regulated level of some variable that is sensed by the central nervous system. In control system terminology, that regulated level is called a ‘setpoint’. In thermoregulation, that implies a set, or reference, or optimal body temperature against which actual body temperature is compared. If there is a discrepancy between the two, an error signal is generated which activates heat loss or heat production mechanisms to return actual body temperature closer to set temperature. The comparator, or signal mixer that compares the two, in other words the thermostat, has been localized in the hypothalamus . . . . E Satinoff. (1983) A re-evaluation of the concept of the homeostatic organization of temperature regulation. In: Handbook of behavioral neurobiology . Eds. E Satinoff, P Teitelbaum, 6 , pp. 443–472. (Plenum Press, New York.) Deep hibernation. . . is homeostasis in slow motion. C P Lyman. (1990) Pharmacological aspects of mammalian hibernation. In: Thermoregulation . Physiology and biochemistry. Eds. E Schonbaum, P Lomax, pp. 415–436. (Pergamon Press, New York.) that we do not really know why there has been such evolutionary pressure for 37 ° C; why not 42 ° ? Or 25°? There have been a number of theories (of course), but none is really entirely convincing. Most of them argue either that 37°C is the optimum for chemical reactions in the body to take place, or that 37°C is the easiest body temperature to maintain in an ambient one of around 25°C, which is the average air temperature in regions where mammals are thought to have evolved. The reason why mammals need to keep their internal temperature (usually called ‘core temperature’) constant is rather easier to understand. The mammalian body is a vast collection of chemical reactions, most of them depending on enzymes. Enzymes act as catalysts: that is, they enable other chemical reactions to occur. - eBook - PDF

Homeostasis

An Integrated Vision

- Fernanda Lasakosvitsch, Sergio Dos Anjos Garnes, Fernanda Lasakosvitsch, Sergio Dos Anjos Garnes(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

There are functional and anatomical connections between the circadian and thermoregulation systems. The circadian system modulates thermoreg-ulatory response to hypothermia and/or cold depending on time and feeding condition. Keywords: fasting, ghrerin, leptin, brown adipose tissue, paraventricular nucleus, arcuate nucleus, suprachiasmatic nucleus 1. Introduction The temperature of the cell(s), tissues, organs, and body is an important factor that deter-mines the biological functions and survival of organisms, from prokaryotes to vertebrates, although the preferred temperature varies. Homeothermic animals can constantly regu-late body temperature (T b ). Thermoregulation is the balance between heat loss and heat © 2018 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. production in the body. The temperature regulation is different among species, and the range of temperature regulation is fairly narrow compared to the larger temperature ranges in the living environment [1]. Homeothermic animals show a circadian T b rhythm, although the goal of thermoregulation is to maintain a constant T b . The T b is higher in the active phase and lower in the inactive phase in both diurnal and nocturnal animals. The T b rhythm is also observed under conditions wherein the influence of physical activity (i.e., heat production) is minimized. For example, circadian T b rhythm is observed even in individuals forced to be on complete bed rest [2]. Results suggested that the circadian T b rhythm can also be regulated. Despite the usual small amplitude of the circadian T b rhythm (e.g., less than 1°C in human beings [3]), the rhythm is still important for preserving energy during the inactive phase. - eBook - PDF

- Charles M Tipton(Author)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

chapter 10 THE TEMPERATURE REGULATORY SYSTEM Elsworth R. Buskirk T EMPERATURE regulation has been demonstrated to occur through two pro-cesses: (1) physiological and (2) behavioral. Behavioral temperature regulation plays its greatest role in coping with cold environments, whereas both physiological and behavioral temperature regulation operate in hot environments, with physio-logical regulation perhaps playing the dominant role. Exercise induces both physio-logical and behavioral regulation by altering heat production, blood flow redistribu-tion for convective heat transfer, and sweating. In this chapter little attention will be paid to behavioral regulation, but many of those who have contributed to our cur-rent understanding of physiological regulation and processes of heat exchange will be identified. Where possible those who first proposed a concept will be featured as well as some of those who either broadened the concept or forcibly brought it to the attention of other investigators through definitive experimentation. Since the liter-ature on temperature regulation and heat exchange is so vast, many investigators who have made significant contributions will not be identified because of space lim-itations. An apology is hereby made for their exclusion. Focusing on the early re-search means that many relatively recent and current studies will not be covered; the reader is referred to the excellent reviews that have appeared such as the recent (1996) Handbook of Physiology, Section 4, Environmental Physiology edited by Fregley and Blatteis (40). One of the very earliest investigators of Body Temperature Regulation was Charles Blagden (12) (1748-1820), who performed a variety of investigations in heated rooms using thermometry. His observations during the period of 1774-1777 are discussed in L. L. Langley's book (72). Not only did Blagden describe both inter-423 - eBook - PDF

- George Spilich(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Proper regulation of internal temperature occurs through the action of the hypothalamus, which receives input from thermoreceptors in the skin and organs throughout the body. In response to a body temperature that is too high (hyperthermia) or too low (hypothermia), your nervous system engages vasodilation or vaso- constriction of blood vessels to dissipate or retain heat, respectively. Comprehension Check 1. Ectotherms and endotherms differ in that ectotherms _____, and endotherms _____. a. rely on the environment to regulate heat; regulate heat through internal means b. require more calories to live; require fewer calories c. cannot survive in cold climates; can survive in cold climates d. have a hypothalamus; do not have a hypothalamus 2. Which region of the nervous system is most involved in tempera- ture regulation? a. frontal lobe b. thermoregulatory nucleus c. hypothalamus d. spinal cord 3. The difference between hyperthermia and hypothermia is that hyperthermia results from _____ and hypothermia results from _____. a. dangerously low body temperature; dangerously high body temperature b. dangerously high body temperature; dangerously low body temperature c. renal dysfunction; circulatory dysfunction d. an inability to direct blood supply to the skin; keeping blood in the body core 4. Overheating normally causes your blood vessels to _____, whereas hypothermia causes those same blood vessels to _____. a. constrict; dilate b. dilate; collapse c. constrict; constrict d. dilate; constrict 7.3 Homeostatic Regulation of Fluids Through Thirst 183 7.3 Homeostatic Regulation of Fluids Through Thirst LO 7.3 Explain and distinguish the two mechanisms that control thirst. Water is essential to life, and that truth is reflected in common wisdom. - eBook - PDF

Heat Loss from Animals and Man

Assessment and Control

- J. L. Monteith, L. E. Mount(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

and IRVING, L. (1950a). Biol. Bull. Mar. Biol. Lab., Woods Hole, 99_, 237 SCHOLANDER, P.F., HOCK, R., WALTERS, V. and IRVING, L. (1950b). Biol. Bull. Mar. Biol. Lab., Woods Hole, £9, 259 SCHOLANDER, P.F. and SCHEVILLE, W.F. (1955). J. appl. Physiol., £, 279 SCHWINGHAMER, J.M. and ADAMS, T. (1969). Fedn Proc. Fedn. Am. Socs exp. Biol., _2§/ 1149 STEBBINS, L.L. (1972). Arctic, 25_, 216 THARP, G.D. and FOLK, G.E. Jr. (1964). J. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. , 14_, 255 WEBSTER, A.J.F. (1967). Br . J. Nutr., 2_, 769 WHITTOW, G.C. (Ed.) (1971). Comparative Physiology of Thermoregulation, Vol. II, Mammals, Academic Press, New York WORSTELL, D.M. and BRODY, S. (1953). Mo. Agric. Sta. Res. Bull., No. 515 WYNDHAM, C.H., MORRISSON, J.F. and WILLIAMS, C.G. (1965). J. appl. Physiol. , _2£, 357 8 DAY NIGHT VARIATION IN HEAT BALANCE J. ASCHOFF, H. BIEBACH, A. HEISE and T. SCHMIDT Max-Planck Institut für Verhaltensphysiologie, D-8J3J Erling-Ancle chs, Germany INTRODUCTION Homeothermic organisms are characterised by a deep-body temperature which has a constant long-term mean, but which also usually fluctuates between a maximal and a minimal value once every 24 h. Constancy of temper-ature depends on a balance between heat production and heat loss. In his last review on the regulation of body temperature, Bazett (1949) states: 'The balance is maintained to some extent by control of heat production but for the most part is attained by regulation of heat loss· 1 The predominance of the regulation of heat loss over the regulation of heat production becomes most evident within the zone of thermoneutrality. One could assume that, at least within this zone, the 24-hour rhythm of deep-body temperature also depends largely on a rhythm of heat loss. Surprisingly, however, research in' this field has long been concerned with attempts to discover a rhythm of heat production, and it is only recently that a rhythm of heat loss has been described in detail.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.