Biological Sciences

Gymnosperms

Gymnosperms are a group of seed-producing plants that do not produce flowers or fruits. They are characterized by the presence of naked seeds, which are not enclosed within an ovary. Gymnosperms include conifers, cycads, ginkgo, and gnetophytes, and are typically found in colder and drier environments. They are important in ecological and economic terms, providing timber, paper, and ornamental plants.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Gymnosperms"

- eBook - PDF

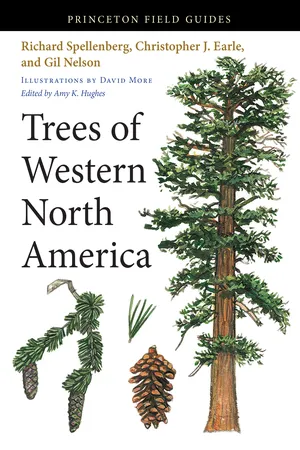

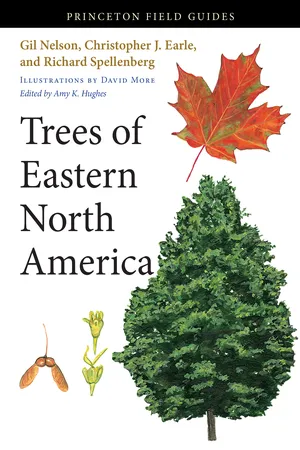

- Richard Spellenberg, Christopher J. Earle, Gil Nelson, David More, Amy K. Hughes(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

26 26 Gymnosperms All Gymnosperms are woody plants. Their seeds do not develop within a closed ovary, as those of the angiosperms do, but are exposed during fertiliza- tion and thereafter, in most cases, develop within a closed vegetative structure. Most Gymnosperms contain aromatic resins in their wood, foliage, and reproductive structures. These resins serve several purposes, among them to discourage herbivory and fungal attack. Most species have tough ever- green foliage, simple or pinnate, with linear leaves or with broader leaves that have simple parallel venation. Gymnosperms includes the conifers, ginkgo, cycads, and gnetophytes. No cycads are native to w. North America, but some are popular ornamental shrubs; the most common is the Sago Palm (cy- cads are often mistaken for palms), Cycas revoluta. There are 12 species of gnetophytes native to w. North America; all are shrubs in the genus Ephe- dra, sometimes called Mormon-tea, and are most common in the desert Southwest but encountered through most of the arid West. Species of Ephedra contain stimulant compounds and have a long his- tory of medicinal use. ■ CONIFERS The conifers are an ecologically and economically important group of about 650 species worldwide. They are usually classified into six families, of which the largest are the pine, podocarp, and cy- press families, each with more than 130 species. The araucaria, yew, and umbrella pine families are much smaller, totaling about 70 species. Of the families treated in this book, it appears that the pine family evolved first, then the araucarias, um- brella pine, cypresses, and yews. Conifers are fundamentally distinguished from the flowering plants (all other trees in this book ex- cept the Ginkgo) by their reproductive structures, their wood, and their resins. Superficially, they are also generally distinguishable by their cones, growth form, and foliage. - eBook - ePub

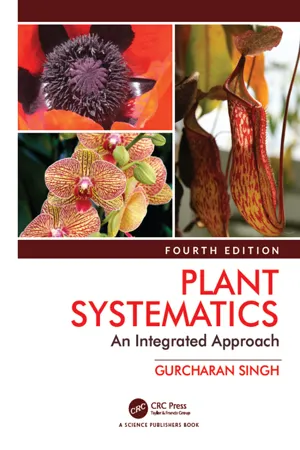

Plant Systematics

An Integrated Approach, Fourth Edition

- Gurcharan Singh(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

12Families of Gymnosperms

Gymnosperms comprise a small group of seed plants characterized by naked seeds (gymno-naked, sperms-seeds) and absence of vessels (except Gnetopsids), endosperm formation independent of fertilization and commonly resulting in halploid endosperm (absence of double fertilization), absence of sieve tubes and companion cells. Group is represented by evergreen trees and shrubs, distributed worldwide and forming extensive forests in North America, Europe and Asia. They represent some of the largest (Sequoiadendrod giganteum of California), tallest (Sequoia sempervirens of California and Oregon) and longest living (Pinus aristata) organisms in the world.Gymnosperms are woody trees or shrubs, herbaceous plants being absent from the group. The plants have well-developed tap root system, sometimes with symbiotic nitrogen fixing cyanobacterium (coralloid roots of Cycas) or mycorrhizae (Pinus). Vascular cylinder has xylem with tracheids with bordered pits and phloem with sieve cells. Leaves lack lateral veins but are compensated by transfusion tissue. Sporangia are heterosporous, microsporangia and megasporangia borne on microsporophylls and megasporophylls, respectively; latter often arranged in distinct cones. Each microsporangium produces numerous microspores arranged in tetrads, since each microspore mother cell undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid microspores. Microspore nucleus undergoes repeated divisions to form male gametophyte, which develops wall to become a pollen grain. The megasporangium, known as ovule, on the other hand, develops a single megaspore mother cell, surrounded by nucellus and integument, with an opening known as micropyle, at the end of integument. Of the four haploid megaspores resulting after meiosis, three degenerate, and only one megaspore is functional. Latter, after repeated nuclear divisions and wall formations produces a female gametophyte with several archegonia, consisting of an enlarged egg cell and two or four neck cells. Pollen grains of Gymnosperms are carried by wind, land on micropyle and adhere to sticky fluid released by the female gametophyte. The pollen germinates to produce a pollen tube, that grows through nucellus and releases two sperms. One fuses with the egg to form zygote after fertilization. Latter develops into an embryo within matured ovule known as seed - Barbara A. Ambrose, Michael D. Purugganan, Barbara A. Ambrose, Michael D. Purugganan(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Chapter 5 Gymnosperms Dennis Wm. Stevenson The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, NY, USAAbstract: This chapter focuses on the oddities of gymnosperm anatomy, morphology, and life cycles. Of particular interest are those seemingly intractable aspects that now seem tractable by combining recent developments in plant molecular biology with plant anatomy, morphology, and development. In most examples, there is available data from plant morphology in the widest sense that can provide the framework for experimental and molecular approaches. These include, but are not limited to, leaf development, senescence, stem growth in diameter, phylloclade development, the structure of reproductive axes and their reciprocal transitions to vegetative growth, free nuclear gametophytes and embryos, and unique features associated with seeds.Keywords: architecture; anatomy; conifers; cycads; embryology; Ginkgo;Gnetales; morphology; teratology.5.1 IntroductionGymnosperms are nonflowering seed plants. There is considerable controversy concerning whether the Gymnosperms are a monophyletic group sister to the flowering plants or a paraphyletic grade (see Doyle this volume). There are four main groups that are generally recognized: (1) cycads (Cycadales), (2) Ginkgo (Ginkgoales), (3) conifers (Taxales plus Pinales), and (4) Gnetales (Ephedra , Gnetum , and Welwitschia ). The relationships between these groups are also controversial and nearly every possible permutation of the six orders have been published (Burleigh & Mathews 2004; Lee et al.- eBook - PDF

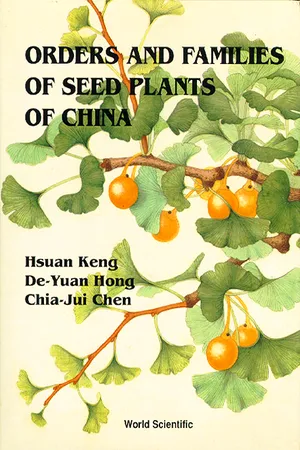

- Chia-jui Chen, De-yuan Hong, Hsuan Keng(Authors)

- 1993(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

THE SEED PLANTS (or SPERMATOPHYTA) The seed plants or Spermatophyta are characterized by the formation of pollen tubes from the pollen grains and by the production of seeds which normally contain an embryo or a dormant plantlet, which becomes active and forms a seedling under favourable conditions. The seed plants constitute one of the largest assemblages in the Plant Kingdom and can be partitioned into two subdivisions as follows. Subdivision I. GYMNOSPERMAE The ovules are borne on the margin of megasporophylls (or carpels, as in cycads) or on the surface of ovuliferous scales (as in conifers), and are more or less naked. There are some 700 species in this subdivision. Subdivision II. ANGIOSPERMAE The carpels surround the ovules and form a closed chamber (the ovary) within which the ovules mature and ripen into seeds. This subdivision includes approximately 250,000 species. 1 SUBDIVISION I Gymnospermae The Gymnosperms, an assemblage of ancient plants with a long geological history, were most abundant during the Palaeozoic and Mesozoic eras. All existing Gymnosperms, numbering about 700 species, are exclusively woody. Tracheids are the chief conducting elements present in the xylem of most Gymnosperms. True vessels are found only in the secondary wood of the Gnetales. A large number of Gymnosperms are important forest trees and garden ornamentals. The Gymnosperms are generally divided into seven or more orders (or classes), some of these orders are depicted by fossil members only. Representatives of all the four living orders exist in China. A simple key to these four orders follows: A. Leaves fan-shaped, deciduous; seeds drupaceous. 2. Ginkgoales A. Leaves various, but not fan-shaped, mostly evergreen; seeds various. B. Leaves pinnately compound, large, crowded at the top of the stem; cones usually large, borne in the center of the leafy crowns, dioecious. - eBook - PDF

- Samantha Fowler, Rebecca Roush, James Wise(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Openstax(Publisher)

Conifers Conifers are the dominant phylum of Gymnosperms, with the most variety of species. Most are tall trees that usually bear scale-like or needle-like leaves. The thin shape of the needles and their waxy cuticle limits water loss through transpiration. Snow slides easily off needle-shaped leaves, keeping the load light and decreasing breaking of branches. These adaptations to cold and dry weather explain the predominance of conifers at high altitudes and in cold climates. Conifers include familiar evergreen trees, such as pines, spruces, firs, cedars, sequoias, and yews (Figure 14.20). A few species are deciduous and lose their leaves all at once in fall. The European larch and the tamarack are examples of deciduous conifers. Many coniferous trees are harvested for paper pulp and timber. The wood of conifers is more primitive than the wood of angiosperms; it contains tracheids, but no vessel elements, and is referred to as “soft wood.” Figure 14.20 Conifers are the dominant form of vegetation in cold or arid environments and at high altitudes. Shown here are the (a) evergreen spruce, (b) sequoia, (c) juniper, and (d) a deciduous gymnosperm: the tamarack Larix larcinia. Notice the yellow leaves of the tamarack. (credit b: modification of work by Alan Levine; credit c: modification of work by Wendy McCormac; credit d: modification of work by Micky Zlimen) Cycads Cycads thrive in mild climates and are often mistaken for palms because of the shape of their large, compound leaves. They bear large cones, and unusually for Gymnosperms, may be pollinated by beetles, rather than wind. They dominated the landscape during the age of dinosaurs in the Mesozoic era (251–65.5 million years ago). Only a hundred or so cycad species persisted to modern times. They face possible extinction, and several species are protected through international conventions. Because of their attractive shape, they are often used as ornamental plants in gardens ( Figure 14.21). - eBook - PDF

The Fundamentals of Horticulture

Theory and Practice

- Chris Bird(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

In the case of the female gametophyte they are contained and protected in a structure called the ovule and produce the egg cells. The male gametophyte is protected within a resistant struc- ture, the pollen grain, enabling it to be dispersed over long distances. On fertilisation the ovule develops and matures into the seed. THE Gymnosperms: CYCADS, GINKGOS AND CONIFERS The Gymnosperms, meaning ‘naked seeds’, represent several distinct lineages that do not enclose their ovules in additional structures. Common garden plants included here are the cycads, ginkgos and conifers and also the Gnetophytes. Although rarely encountered in gardens they include joint firs (Ephedra), charac- terised by their mass of green jointed leafless stems, and the strange Welwitschia, which just produces two strap-like leaves growing continuously from a woody base. Gymnosperms have not fully eliminated the need for water in their life cycle. The ovule produces a ‘pollen drop’ at the apex so providing a liquid medium for the sperm to reach the egg. In the case of cycads and ginkgos the pollen grain contains free- swimming sperm, a character shared in common with earlier plant lineages. In conifers a pollen tube germinates and grows towards the female gametophyte allowing the cells of the male gametophyte to effect pollination. Cycads (Cycadopsida) reached the pinnacle of their diversity during the age of the dinosaurs, only 210 species survive today in the tropical and subtropical parts of the world. Their large orna- mental frond-like leaves, usually borne on a distinct trunk, make them highly desirable as architectural garden plants, large speci- mens being expensive and sometimes leading to their illegal collection from the wild. Beetles are common pollinators, making cycads one of the first lineages to evolve insect pollination. - eBook - ePub

Phytochemistry of Australia's Tropical Rainforest

Medicinal Potential of Ancient Plants

- Cheryll J. Williams(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- CSIRO PUBLISHING(Publisher)

4 Ancient GymnospermsThe breakup of Gondwana around 80 mya forced the native Gymnosperms to adapt and diversify in response to warmer, drier conditions. Even so, various genera managed to retreat to the forest refuges of New Zealand, Australia and South America, which continue to provide sanctuary for some of the oldest conifer lineages in existence. The native gymnosperm representatives are cycads (Cycadaceae and Zamiaceae) and the native conifers (Araucariaceae, Cupressaceae and Podocarpaceae).The Gymnosperms were an integral component of the forests that once covered Gondwana: ‘The origin of seed plants over 320 million years ago … was one of the most significant events in the evolution of terrestrial vegetation, an adaptive breakthrough that allowed colonization of habitats that were inhospitable to spore-producing plants and triggered a Lower Carboniferous diversification of vascular plants. This event also significantly facilitated the evolutionary radiation of other terrestrial organisms … The cone-bearing Cycads and Southern Conifers are the most ancient of living seed plants, little changed from ancestors that flourished in the Jurassic Period, termed the “Age of the Conifers and Cycads” between 136 and 195 million years ago … The flora of this Period was a cosmopolitan flora of conifers, cycads, ferns, seedferns, ginkgos, herbaceous lycopods and horsetails’ [1 ].Gymnosperm diversity plummeted across the globe around 125–90 mya due to major environmental changes. Then, around 35 mya, climate change appears to have sent many more lineages to extinction, with the survivors establishing new coping strategies in a different world [2 ; 3 - eBook - PDF

- Gurnah, Akinloye(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Agri Horti Press(Publisher)

This has two consequences–firstly, it means it is not fully resistant to desiccation, and secondly, sperm do not have to “burrow” to access the archegonia of the megaspore. The first “spermatophytes” (literally:seed plants)–that is, the first plants to bear true seeds–were proGymnosperms called pteridosperms: literally, “seed ferns”. They ranged from trees to small, rambling shrubs; like most early proGymnosperms, they were woody plants with fern-like foliage. They all bore ovules, but no cones, fruit or similar. While it is difficult to track the early evolution of seeds, we can trace the lineage of the seed ferns from the simple trimerophytes through homosporous Aneurophytes. This seed model is shared by basically all Gymnosperms (literally: “naked seeds”), most of which encase their seeds in a woody or fleshy (the yew, for example) cone, but none of which fully enclose their seeds. The angiosperms (“vessel seeds”) are the only group to fully enclose the seed, in a carpel. Fully enclosed seeds opened up a new pathway for plants to follow: that of seed dormancy. The embryo, completely isolated from the external atmosphere and hence protected from desiccation, could survive some years of draught before germinating. Gymnosperm seeds from the late Carboniferous have been found to contain embryos, suggesting a lengthy gap between fertilisation and germination. This period is associated with the entry into a greenhouse earth period, with an associated increase in aridity. This suggests that dormancy arose as a response to drier climatic conditions, where it became advantageous to wait for a moist period before germinating. This evolutionary breakthrough appears to have opened a floodgate: previously inhospitable areas, such as dry mountain slopes, could now be tolerated, as were soon covered by trees. - eBook - ePub

Ancient Plants

Being a Simple Account of the past Vegetation of the Earth and of the Recent Important Discoveries Made in This Realm of Nature

- Marie Carmichael Stopes(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

The resinous character of Gymnosperm wood probably greatly assisted its preservation, and fragments of it are very common in rocks of all ages, generally preserved in silica so as to show microscopic structure. The isolated wood of Gymnosperms, however, is not very instructive, for from the wood alone (and usually it is just fragments of the secondary wood which are preserved) but little of either physiological or evolutional value can be learned. When twigs with primary tissues and bark and leaves attached are preserved, then the specimens are of importance, for their true character can be recognized. Fortunately among the coal balls there are many such fragments, some of which are accompanied by fruits and male cones, so that we know much of the Palæozoic Gymnosperms, and find that in some respects they differ widely from those now living.There is, therefore, much more to be said about the fossil Gymnosperms than about the Angiosperms, both because of the better quality of their preservation and because their history dates back to a very much earlier period than does the Angiospermic record. Indeed, we do not know when the Gymnosperms began; the well-developed and ancient group of Cordaiteæ was flourishing before the Carboniferous period, and must therefore date back to the rocks of which we have no reliable information from this point of view, and the origin of the Gymnosperms must lie in the pre-Carboniferous period.The group of Gymnosperms includes a number of genera of different types, most of which may be arranged under seven principal families. In a sketch of this nature it is, of course, quite impossible to deal with all the less-important families and genera. Those that will be considered here are the following:—Coniferales (see p. 90 - eBook - PDF

- Livia Wanntorp, Louis P. Ronse De Craene(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Flowers on the Tree of Life, ed. Livia Wanntorp and Louis P. Ronse De Craene. Published by Cambridge University Press. © The Systematics Association 2011. 2 Spatial separation and developmental divergence of male and female reproductive units in Gymnosperms, and their relevance to the origin of the angiosperm flower Richard M. Bateman, Jason Hilton and Paula J. Rudall 2.1 Introduction: aims and terminology It is now generally accepted that angiosperms are monophyletic and are derived from a gymnospermous ancestor. It is also widely recognized that, among extant seed-plants, angiosperm reproductive units are typically bisexual (= bisporang- iate, hermaphrodite) and are termed flowers, whereas putatively comparable units produced by the four groups of Gymnosperms represented in the extant flora are typically unisexual, either functionally dioecious (cycads, Ginkgo, gnet- aleans) or a more complex admixture of dioecious and monoecious taxa (conifers) (e.g. Tandre et al., 1995). Individual extant Gymnosperms are either monoecious, bearing male and female units on separate axes of the same plant, or dioecious, each individual bearing units of only one gender (note: in this chapter, the terms ‘male’ and ‘female’ are used consistently as colloquial shorthand for the ovu- liferous and (pre)polleniferous conditions, respectively). A positive correlation MALE AND FEMALE REPRODUCTIVE UNITS IN Gymnosperms 9 with dispersal mechanism is evident, monoecious extant Gymnosperms typic- ally producing dry, wind-dispersed seeds and dioecious Gymnosperms bearing fleshy, often animal-dispersed seeds (cf. Givnish, 1980; Donoghue, 1989). Further terminological clarifications are needed. Bateman et al. ( 2006, p. 3472) reviewed relevant definitions before defining a flower as ‘a determinate axis bear- ing megasporangia that are surrounded by microsporangia and are collectively subtended by at least one sterile laminar organ’. - eBook - PDF

- Gil Nelson, Christopher J. Earle, Richard Spellenberg, David More, Amy K. Hughes(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

Leaves Alternate, Bipinnately or Tripinnately Compound Devil’s Walkingstick, p. 144 Kentucky Coffeetree, p. 260 Pride-of-Barbados, p. 252 Sweet Acacia, p. 266 Jerusalem Thorn, p. 252 Silktree, p. 270 Royal Poinciana, p. 256 Chinaberry-tree, p. 404 Water Locust, p. 258 Horseradish-tree, p. 418 Goldenrain Tree, p. 642 33 LEAF KEYS 34 Gymnosperms All Gymnosperms are woody plants. Their seeds do not develop within a closed ovary, as those of the angiosperms do, but are exposed during fer- tilization and thereafter, in most cases, develop within a closed vegetative structure. Most gym- nosperms contain aromatic resins in their wood, foliage, and reproductive structures. These resins serve several purposes, among them to discourage herbivory and fungal attack. Most species have tough evergreen foliage, simple or pinnate, with linear leaves or with broader leaves that have sim- ple parallel venation. Gymnosperms include the conifers, ginkgo, cycads, and gnetophytes. The only cycad native to our area is the Coontie (Zamia pumila L.), a small shrub native to Fla. and se. Ga. that bears a crown of sharp-edged pinnate fronds, each 20–100 cm long. The Coontie, like most cycads, is often mistaken for a palm, but it bears its seeds in cones. The only gnetophyte in e. North America is Clap-weed (Ephedra antisyphilitica Berland. ex C.A. Meyer), which grows as a shrub to 1 m tall in Tex. and Okla. at the extreme w. edge of our area. Species of Ephedra occur through much of the Northern Hemisphere and have a long history of medicinal use. ■ CONIFERS The conifers are an ecologically and economically important group of about 650 species worldwide. They are usually classified into 6 families, of which the largest are the pine, podocarp, and cypress families, each containing more than 130 species. The araucaria, yew, and umbrella pine families are much smaller, totaling about 70 species.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.