Chemistry

Benzene Derivatives

Benzene derivatives are organic compounds that are derived from benzene by replacing one or more hydrogen atoms with other functional groups. These derivatives exhibit diverse chemical and physical properties, making them important in various industrial and biological processes. Common benzene derivatives include toluene, phenol, aniline, and nitrobenzene, each with distinct reactivity and applications.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Benzene Derivatives"

- eBook - ePub

Organic Chemistry

An Acid-Base Approach, Third Edition

- Michael B. Smith(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

19 Aromatic Compounds and Benzene Derivatives

DOI: 10.1201/9781003174929-19The video clips for this chapter are available at: https://routledgetextbooks.com/textbooks/9780367768706/chapter-19.phpThe scientist photographs are also available at: https://routledgetextbooks.com/textbooks/9780367768706/image-gallery.phpBenzene was identified as a special type of hydrocarbon in Section 5.9. Benzene and derivatives are aromatic hydrocarbons with one ring or several rings fused together. The aromatic character of benzene and derivatives have special stability, which imparts a unique chemical profile.To begin this chapter, you should know the following points:- Resonance and resonance-stability (Sections 2.6 and 6.3.1).

- Nomenclature and structure of alkenes, alkyl halides, alcohols, amines, aldehydes, and ketones (Sections 5.1, 5.2 5.85, and 5.6).

- Carboxylic acids and carboxylic acid derivatives (Chapter 18 ).

- The structure and nature of π-bonds (Section 5.1).

- Reactivity of alkenes (Sections 10.1–10.6).

- E2 elimination reactions of alkyl halides (Sections 12.1–12.3).

- E1 elimination reactions (Section 12.4).

- The CIP rules (Section 9.2).

- Electron-releasing and withdrawing substituents (Sections 3.8, 6.3.2).

- Brønsted-Lowry acid-base reactions of alkenes (Sections 10.5–10.7).

- Carbocation stability (Sections 7.2.1, 10.1 and 10.3).

- Leaving groups (Sections 11.1–11.3 and 18.4).

- Lewis acids and Lewis bases (Sections 2.7 and 6.8).

- Rate of reaction (Section 7.11).

- Reduction of functional groups (Sections 17.2–17.5).

19.1 Benzene and Aromaticity

Structure of BenzeneBenzene is a liquid first isolated from an oily condensate deposited from compressed illuminating gas by Michael Faraday (England; 1791–1867) in 1825. Benzene is a hydrocarbon and the parent of a large class of compounds known as aromatic hydrocarbons. In 1834, Eilhard Mitscherlich (Germany; 1794–1863) established the formula to be C6 H6 and named the material benzin. Justus Liebig (Germany; 1803–1873) changed the name to benzol. In 1837, August Laurent (France; 1807–1853) proposed the name pheno (Greek; I bear light) since it was isolated from illuminating gas. The name was not adopted, but has given rise to the term phenyl for a benzene ring used as a substituent C6 H5 - eBook - PDF

Organic Chemistry

Made Simple

- S. K. Murthy, S. S. Nathan(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Made Simple(Publisher)

PART III AROMATIC COMPOUNDS This page intentionally left blank CHAPTER TWELVE BENZENE AND ITS DERIVATIVES Usually the study of organic chemistry is divided into four parts— aliphatic, alicyclic, aromatic, and heterocyclic. The aliphatic and ali-cyclic compounds have already been dealt with in Part II. Aromatic compounds will be studied in this part of the book. The aromatic compounds are derived from a hydrocarbon benzene (CeHö) containing a closed ring of six carbon atoms. The word aromatic, to designate benzene and its derivatives, owes its origin to the fact that some of these compounds have pleasant odours. KEKUL£, the great German chemist, who gave us the correct idea of the valence of the carbon atom, recognized the fact that certain substances from resins, balsams, and essential oils did not fit into the general classification of the carbon compounds known at that time (i.e. the open-chain com-pounds). He found that such substances as oil of bitter almonds, benzoic acid, and benzyl alcohol from gum benzoin and toluene from tolu balsam contained at least six carbon atoms and retained a six-carbon unit through ordinary chemical changes and degradation. These compounds, though they had a low hydrogen content, did not show the expected properties associated with unsaturation. The simplest member of the group was recognized as benzene. COAL—SOURCE OF AROMATIC COMPOUNDS The major source of aromatic chemicals for a long time has been coal. In recent years petroleum has become a significant alternative source of some of these compounds. We shall first outline the processes whereby aromatic compounds are obtained from coal. Coal when heated to about 1,000° C, in the absence of air in a retort, is converted into coke. Coke is used in metallurgical operations for reductions of ores and as a source of heat. On heating coal, volatile substances come out and are passed through a condenser into a sulphuric acid scrubbing solution. - eBook - ePub

- James G. Speight(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

The solvent properties of the two are similar, but toluene is less toxic and has ahigh0boiling constituents wider liquid range. Aromatic hydrocarbon derivatives, like paraffin hydrocarbon derivatives, react by substitution, but by a different mechanisms under milder reaction conditions. Aromatic compounds react by additions only under several reaction conditions. For example, electrophilic substitution of benzene using nitric acid produces nitrobenzene under normal conditions, while the addition of hydrogen to benzene occurs in presence of catalyst only under high pressure to give cyclohexane. Monosubstitution can occur at any one of the six equivalent carbon atoms of the ring. Most of the monosubstituted benzenes have common names such as toluene (methylbenzene), phenol (hydroxybenzene), and aniline (aminobenzene). When two hydrogens in the ring are substituted by the same reagent, three isomers are possible. The prefixes ortho, meta, and para are used to indicate the location of the substituents in 1,2-; 1,3-; or 1,4-positions, for example, xylene isomers. Benzene is an important chemical intermediate and is the precursor for many commercial chemicals and polymers such as phenol, styrene for polystyrene derivatives, and caprolactam for nylon 6. Chapter 10 discusses chemicals based on benzene. Benzene (C 6 H 6) is the most important aromatic hydrocarbon. It is the precursor for many chemicals that may be used as end products or intermediates. Almost all compounds derived directly from benzene are converted to other chemicals and polymers. For example, hydrogenation of benzene produces cyclohexane. Oxidation of cyclohexane produces cyclohexanone, which is used to make caprolactam for nylon manufacture. Due to the resonance stabilization of the benzene ring, it is not easily polymerized. However, products derived from benzene such as styrene, phenol, and maleic anhydride can polymerize to important commercial products due to the presence of reactive functional groups - eBook - PDF

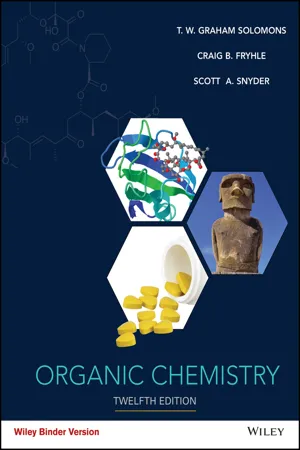

- T. W. Graham Solomons, Craig B. Fryhle, Scott A. Snyder(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

As we shall see in Section 14.3, benzene does not show the behavior expected of a highly unsaturated compound. During the latter part of the nineteenth century the Kekulé–Couper–Butlerov theory of valence was systematically applied to all known organic compounds. One result of this effort was the placing of organic compounds in either of two broad categories; com- pounds were classified as being either aliphatic or aromatic. To be classified as aliphatic meant then that the chemical behavior of a compound was “fat-like”; now it means that the compound reacts like an alkane, an alkene, an alkyne, or one of their derivatives. To be classified as aromatic meant then that the compound had a low hydrogen-to-carbon Methyl salicylate (in oil of wintergreen) OH OCH 3 O Benzaldehyde (in oil of almonds) H O Benzene or Eugenol (in oil of cloves) HO OCH 3 Cinnamaldehyde (in oil of cinnamon) H O Vanillin (in oil of vanilla) OCH 3 H HO O Acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin) OH O O O One of the π molecular orbitals of benzene, seen through a mesh representation of its electrostatic potential at its van der Waals surface. 14.2 NOMENCLATURE OF Benzene Derivatives 619 ratio and that it was “fragrant.” Most of the early aromatic compounds were obtained from balsams, resins, or essential oils. Kekulé was the first to recognize that these early aromatic compounds all contain a six-carbon unit and that they retain this six-carbon unit through most chemical transformations and degradations. Benzene was eventually recognized as being the parent compound of this new series. It was not until the development of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, however, that a reasonably clear understanding of its structure emerged. 14.2 NOMENCLATURE OF Benzene Derivatives Two systems are used in naming monosubstituted benzenes. • In many simple compounds, benzene is the parent name and the substituent is simply indicated by a prefix. - eBook - ePub

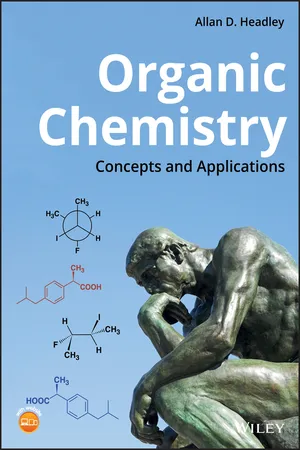

Organic Chemistry

Concepts and Applications

- Allan D. Headley(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Benzene is another one of these organic compounds with a very distinctive aroma and is responsible for the odor of coal distillate. It was discovered that these organic compounds all have a special feature, which is described as aromaticity, and as result, these compounds are referred to as aromatic compounds. As you can imagine, there are numerous compounds that can be described as aromatic compounds. There are other aromatic compounds that may not have a distinct characteristic odor. Some include aspirin, morphine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, nicotine, vitamin E, and estrone. It is difficult to study all aromatic compounds individually, so we will carry out our study of aromatic compounds on the most common aromatic compound, benzene, and apply the knowledge gained to other compounds that are similar and aromatic.Benzene was isolated from compressed illuminating gas in 1825 by Michael Faraday of the Royal Institution. In 1834, Eilhardt Mitscherlich of the University of Berlin synthesized benzene by heating benzoic acid with calcium oxide and he also showed that the molecular formula of benzene is C6 H6 . Today, benzene is obtained primarily from the distillation of petroleum, and it is used in the synthesis of many useful chemicals in our society. Benzene is also a very common solvent that is used in most chemical labs, both industrial and academic. However, it was removed from teaching labs, since it was shown to cause cancer when given to laboratory animals in very large dosage. Benzene is absorbed in the blood stream from inhalation and is converted to phenols and excreted by the liver. Benzene causes skin irritation; it is thought to cause leukemia. If absorbed in the blood, it will increase the number of white blood cells and it also causes damage to bone marrow. However, it is still sometimes used, under very controlled conditions, in industrial and research labs.Since most of the chemical properties of compounds in this very large category of aromatic compounds are similar, we will study in detail the chemistry of only one of these compounds, benzene. By knowing the chemical and physical properties of benzene, we will be able to predict the properties of other aromatic compounds. In this chapter, we will first define aromaticity in a chemical sense and then apply that definition to other molecules to determine if they are aromatic or not. In the later sections of the chapter, we will examine the reactions of aromatic compounds.17.2 Structure and Properties of Benzene

It was shown that the chemical formula of benzene is C6 H6 . Based on our knowledge of the number of hydrogens that are bonded to the carbons of saturated hydrocarbons, it is obvious that benzene is not a saturated hydrocarbon. In 1866, Friedrich Kekulé proposed that benzene had a cyclic structure with three alternating double bonds, as shown in Figure 17.1 - eBook - PDF

Foundations of Chemistry

An Introductory Course for Science Students

- Philippa B. Cranwell, Elizabeth M. Page(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

15 The chemistry of aromatic compounds At the end of this chapter, students should be able to: • Understand the structure of benzene and other aromatic compounds • Be able to describe and explain electrophilic aromatic substitution, S E Ar • Determine if a ring substituent is activating or deactivating • Compare and contrast the reactivity of benzene, phenol, and aniline with electrophiles 15.1 Benzene 15.1.1 The structure of benzene Benzene , C 6 H 6 , is a molecule that can be described as aromatic . This is because when benzene and benzene-containing compounds were first isolated, they were noted to smell pleasant, so their name was derived from the Greek ‘ aroma ’ , meaning spice, which was then used in Latin to mean ‘ sweet smell ’ . Benzene is a simple aromatic compound that is often studied in undergraduate courses. It is a colourless liquid with a slightly sweet odour and is fully aromatic. Benzene can be represented in a number of ways depending upon what information needs to be depicted (Figure 15.1). Each carbon atom in the benzene molecule is trigonal planar in geometry, with a bond angle of 120 between the other two carbon atoms and the hydro-gen. In terms of the bonding, there are three σ bonds and one π bond per carbon atom. The π bond is formed by an electron in the p orbital of one carbon atom overlapping with an electron in a p orbital on an adjacent carbon atom. This overlap causes a cyclic system of bonding p orbitals (or π bonds) to be formed, where the electrons are free to move around the ring. The movement of electrons in this manner is called delocalisation , and benzene can be said to have a delocalised electron system above and below the ring . Benzene has a delocalised electron system above and below the ring. For a refresher on the shapes of molecules, please see Chapter 2. Foundations of Chemistry: An Introductory Course for Science Students , First Edition. Philippa B. Cranwell and Elizabeth M. Page. © 2021 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Research World(Publisher)

To reflect the delocalized nature of the bonding, benzene is often depicted with a circle inside a hexagonal arrangement of carbon atoms: The delocalized picture of benzene has been contested by Cooper, Gerratt and Raimondi in their article published in 1986 in the journal Nature. They showed that the electrons in benzene are almost certainly localized, and the aromatic properties of benzene originate from spin coupling rather than electron delocalization. This view has been supported in the next-year Nature issue, but it has been slow to permeate the general chemistry community. As is common in organic chemistry, the carbon atoms in the diagram above have been left unlabeled. Realizing each carbon has 2p electrons, each carbon donates an electron into the delocalized ring above and below the benzene ring. It is the side-on overlap of p-orbitals that produces the pi clouds. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Benzene occurs sufficiently often as a component of organic molecules that there is a Unicode symbol in the Miscellaneous Technical block with the code U+232C ( ⌬ ) to represent it with three double bonds, and U+23E3 for a delocalized version. Substituted Benzene Derivatives Many important chemicals are derived from benzene by replacing one or more of its hydrogen atoms with another functional group. Examples of simple Benzene Derivatives are phenol, toluene, and aniline, abbreviated PhOH, PhMe, and PhNH 2 , respectively. Linking benzene rings gives biphenyl, C 6 H 5 –C 6 H 5 . Further loss of hydrogen gives fused aromatic hydrocarbons, such as naphthalene and anthracene. The limit of the fusion process is the hydrogen-free allotrope of carbon, graphite. In heterocycles, carbon atoms in the benzene ring are replaced with other elements. The most important derivatives are the rings containing nitrogen. Replacing one CH with N gives the compound pyridine, C 5 H 5 N. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Library Press(Publisher)

To reflect the delocalized nature of the bonding, benzene is often depicted with a circle inside a hexagonal arrangement of carbon atoms: The delocalized picture of benzene has been contested by Cooper, Gerratt and Raimondi in their article published in 1986 in the journal Nature. They showed that the electrons in benzene are almost certainly localized, and the aromatic properties of benzene originate from spin coupling rather than electron delocalization. This view has been supported in the next-year Nature issue, but it has been slow to permeate the general chemistry community. As is common in organic chemistry, the carbon atoms in the diagram above have been left unlabeled. Realizing each carbon has 2p electrons, each carbon donates an electron into the delocalized ring above and below the benzene ring. It is the side-on overlap of p-orbitals that produces the pi clouds. WT ____________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ____________________ Benzene occurs sufficiently often as a component of organic molecules that there is a Unicode symbol in the Miscellaneous Technical block with the code U+232C ( ⌬ ) to represent it with three double bonds, and U+23E3 ( ) for a delocalized version. Substituted Benzene Derivatives Many important chemicals are derived from benzene by replacing one or more of its hydrogen atoms with another functional group. Examples of simple Benzene Derivatives are phenol, toluene, and aniline, abbreviated PhOH, PhMe, and PhNH 2 , respectively. Linking benzene rings gives biphenyl, C 6 H 5 –C 6 H 5 . Further loss of hydrogen gives fused aromatic hydrocarbons, such as naphthalene and anthracene. The limit of the fusion process is the hydrogen-free allotrope of carbon, graphite. In heterocycles, carbon atoms in the benzene ring are replaced with other elements. The most important derivatives are the rings containing nitrogen. Replacing one CH with N gives the compound pyridine, C 5 H 5 N. - eBook - ePub

- John T. Moore, Richard H. Langley(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- For Dummies(Publisher)

Part 2Discovering Aromatic (And Not So Aromatic) Compounds

IN THIS PART …- Examine aromatic systems, including the spectroscopy of aromatic compounds.

- Organize some aromatic substitutions by electrophiles.

- Get nucleophiles in on the aromatic substitution action.

Passage contains an image Chapter 6

Introducing Aromatics

IN THIS CHAPTERExploring benzeneCoping with the aromatic familyGetting acquainted with heterocyclic aromatic compoundsShedding light on the spectroscopy of aromatic compoundsOrganic chemistry has two main divisions. One division deals with aliphatic (fatty) compounds, the first compounds you encountered in Organic Chemistry I. Methane is a typical example of this type of compound. The second division includes the aromatic (fragrant) compounds, of which benzene is a typical example.Compounds in the two groups differ in a number of ways. The two differ chemically in that the aliphatic undergo free-radical substitution reactions and the aromatic undergo ionic substitution reactions. In this chapter, we examine the basics of both aromatic and heterocyclic aromatic compounds, concentrating on benzene and related compounds.Benzene: Where It All Starts

Benzene is the fundamental aromatic compound. An understanding of the behavior of many other aromatic compounds is much easier if you first gain an understanding of benzene. For this reason, you may find it useful to examine a few key characteristics of benzene, which we discuss in the following sections.Figuring out benzene’s structure

Benzene was first isolated in 1825 from coal tar. Later, chemists determined that it had the molecular formula C6 H6 . Further investigation of its chemical behavior showed that benzene was unlike other hydrocarbons in both structure and reactivity.Chemists proposed many structures for benzene. However, the facts didn’t support any of the possibilities until Kekulé proposed a ring structure in 1865. Some of the proposed structures, including Kekulé’s, are shown in Figure 6-1 - eBook - PDF

- T. W. Graham Solomons, Craig B. Fryhle, Scott A. Snyder(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Most compounds that were known then had a far greater propor- tion of hydrogen atoms, usually twice as many. Benzene, having the formula of C 6 H 6 , should be a highly unsaturated compound because it has an index of hydrogen deficiency equal to 4. Eventually, chemists began to recognize that benzene was a member of a new class of organic compounds with unusual and interesting properties. As we shall see in Section 14.3, benzene does not show the behavior expected of a highly unsaturated compound. During the latter part of the nineteenth century the Kekulé–Couper–Butlerov theory of valence was systematically applied to all known organic compounds. One result of this effort was the placing of organic compounds in either of two broad categories; com- pounds were classified as being either aliphatic or aromatic. To be classified as aliphatic meant then that the chemical behavior of a compound was “fat-like”; now it means that the compound reacts like an alkane, an alkene, an alkyne, or one of their derivatives. To be classified as aromatic meant then that the compound had a low hydrogen-to-carbon One of the π molecular orbitals of benzene, seen through a mesh representation of its electrostatic potential at its van der Waals surface. 14.2 NOMENCLATURE OF Benzene Derivatives 619 ratio and that it was “fragrant.” Most of the early aromatic compounds were obtained from balsams, resins, or essential oils. Kekulé was the first to recognize that these early aromatic compounds all contain a six-carbon unit and that they retain this six-carbon unit through most chemical transformations and degradations. Benzene was eventually recognized as being the parent compound of this new series. It was not until the development of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, however, that a reasonably clear understanding of its structure emerged. 14.2 NOMENCLATURE OF Benzene Derivatives Two systems are used in naming monosubstituted benzenes.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.