Chemistry

Radioactive Isotopes

Radioactive isotopes are atoms of the same element with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons, resulting in varying atomic masses. These isotopes are unstable and undergo radioactive decay, emitting radiation in the form of alpha, beta, or gamma particles. They are used in various applications, including medical imaging, cancer treatment, and dating archaeological artifacts.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Radioactive Isotopes"

- eBook - PDF

Soil and Environmental Analysis

Modern Instrumental Techniques

- Keith A. Smith, Malcolm S. Cresser, Keith A. Smith, Malcolm S. Cresser(Authors)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

8 Measurement of Radioisotopes and Ionizing Radiation Olivia J. Marsden and Francis R. Livens The University of Manchester ; Manchester ; England I. INTRODUCTION Approximately 1700 different isotopes are known, of which around 275 are stable. The remainder are radioactive; that is, their nuclear configurations are unstable and can change to more stable forms by nuclear transformations that are collectively known as radioactive decay. These radioactive decay processes are accompanied by the emission of particles and/or photons from the nucleus. Isotopes (or nuclides) are distinguished by the number of protons and neutrons (collectively known as nucleons) they contain and are commonly designated using mass number (A: number of protons + neutrons) and atomic number (Z: number of protons). For example, l64C is an isotope of carbon in which the nucleus contains 14 nucleons, of which six are protons. The proton number defines the chemical identity of the atom, since the proton charge must be balanced by the appropriate number of electrons, but it also duplicates the information provided by the chemical symbol and, in practice, is often omitted, hence 1 4 C. Differences in the neutron number may control the stability, or otherwise, of a nucleus but have only subtle effects on chemistry, although these can be exploited in studies of stable isotope fractionation in natural systems, for example 2 H / 1 H, 1 3 C/ 1 2 C, 1 5 N / 1 4 N, 1 7 0 / 1 6 0, 3 4 S/32S (see Chap. 9). Only a minority of the unstable isotopes are formed in nature. Most are man-made, and the majority of these are available only in such small amounts, or are so short-lived or both, that they are unlikely to be 345 346 Marsden and Livens Figure 1 Isotopes produced by the decay of 2 3 8 U. encountered in the environment or to be of any use as radiotracers. The naturally occurring radioisotopes fall into three groups: 1. - eBook - ePub

Geochemistry

Pathways and Processes

- Harry Y. McSween, Steven M. Richardson, Maria Uhle(Authors)

- 2003(Publication Date)

- Columbia University Press(Publisher)

chapter 2 , we saw that only ∼260 of the 1700 known nuclides are stable, so we can infer that nuclide stability is the exception rather than the rule. Most of the known Radioactive Isotopes do not occur in nature. Although some of these may have occurred naturally in the distant past, their decay rates were so rapid that they have long since been transformed into other nuclides. In most cases, Radioactive Isotopes that are of interest to geochemists require very long times for decay or are produced continually by naturally occurring nuclear reactions.In chapter 13 , we explored how variations in stable isotopes are caused by mass fractionation during the course of chemical reactions or physical processes. With the exception of radioactive 14 C and a few other nuclides, the atomic masses of most of the unstable isotopes of geochemical interest are very large, so that mass differences with other nuclides of the same element are minuscule. Consequently, these isotopic systems can be considered to be immune to mass fractionation processes. Thus, all of the measured variations in these nuclides are normally ascribed to radioactive decay.Decay MechanismsRadioactivity is the spontaneous transformation of an unstable nuclide (the parent) into another nuclide (the daughter). The transformation process, calledradioactive decay, results in changes in N (the number of neutrons) and Z (the number of protons) of the parent atom, so that another element is produced. Such processes occur by emission or capture of a variety of nuclear particles. Isotopes produced by the decay of other isotopes are said to be radiogenic. The radiogenic daughter may be stable or unstable; if it is unstable, the decay process continues until a stable nuclide is produced.Beta decay involves the emission of negatively charged beta particles (electrons emitted by the nucleus), commonly accompanied by radiation in the form of gamma rays. This is equivalent to the transformation of a neutron into a proton and an electron. As illustrated in figure 14.1 , Z increases by one and N - eBook - PDF

- Douglas P. Heller, Carl H. Snyder(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Today we recognize that the radiation emitted by these elements originates within their unstable nu- clei as the nuclei undergo spontaneous radioactive decay. What is it about certain atomic nuclei, also known as nuclides, that makes them unstable and prone to radio- active decay? We generally find either of two conditions underlying radioactivity: 1. Radioactive nuclei have high atomic numbers. All nuclides with 84 or more protons are radioactive. This means that all elements in the periodic table s we’ve seen in previous chapters, atoms con- stitute the fundamental units of the matter that forms our everyday world, and atoms can combine with one another to form a variety of chemical compounds. These combinations of atoms occur through the transfer or the sharing of electrons in the valence shells—the outermost quantum shells—of the combining atoms. In this section, we shift our focus from these outlying electrons to the nucleus, which (as we’ve also seen in earlier chapters) occupies a remarkably small volume at the center of the atom. We’ll begin our examination of the nucleus with the discovery of radioactivity, which emanates from within the nucleus itself. This remarkable discovery, which occurred near the dawn of the 20th century, set in motion a series of events that would usher in the atomic age. Discovery of Radioactive Decay In 1896, Antoine Henri Becquerel, a French physicist work- ing in Paris, made an unexpected and startling discovery. Becquerel was investigating a phenomenon called phospho- rescence, which causes some substances to glow visibly for a short time after they have been exposed to some forms of radiation, including the ultraviolet radiation of sunlight. He thought, incorrectly as it turns out, that X-rays might accom- pany this phosphorescence. - eBook - PDF

Isotopes in Nanoparticles

Fundamentals and Applications

- Jordi Llop, Vanessa Gomez-Vallejo, Jordi Llop, Vanessa Gomez-Vallejo(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Jenny Stanford Publishing(Publisher)

In the latter state, the nucleus has an excess of internal energy and tends to move to a more stable state. The process by which the atomic nucleus moves from an unstable to a more stable state is called radioactive decay. Radioactive decay is spontaneous and is accompanied by the emission of particles and/or electromagnetic radiation. The unstable nucleus is called a radioactive atom or radionuclide. 145 During radioactive decay, the unstable atoms can become a different element via a process known as transmutation. This is the case in radioactive processes that result in the emission of alpha particles ( a , or 4 He 2+ ), electrons ( b – ), or positrons ( b + ). As an example, fluorine-18 ( 18 F) has nine protons and nine neutrons in its nucleus and is a positron emitter; on spontaneous decay a positron is emitted and, consequently, one of the protons becomes a neutron. The newly formed element, which has eight protons and ten neutrons, is oxygen-18 ( 18 O). Radioactive decay can also occur via electron capture (when a nucleus captures an orbiting electron, thereby converting a proton into a neutron with consequent transmutation), by emission of gamma ( g ) rays, by emission of a neutron, or by ejection of an orbital electron due to interaction with an excited nucleus in a process called “internal transition”. In the latter three decay modalities, the atoms before and after radioactive decay correspond to the same element because the number of protons remains unchanged and transmutation does not occur. Radioactive atoms exist in nature (and indeed are continuously produced naturally) and can be found in air, water, soil, or even living organisms. They can also be produced artificially using different technologies. Over 1500 radionuclides, both natural and artificial, have been identified. 6.2.2 Radioactive Decay Equations Radioactive decay is a stochastic process in which, according to quantum theory, it is impossible to predict when a specific atom will decay. - eBook - PDF

- Satyanarayana, D(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Daya Publishing House(Publisher)

Chapter 5 Radioactive Nuclides The atomic weight of any element is the average weight of its isotopes taking into account their abundance. For example, the abundances of the isotopes of potassium, K-39, K-40 and K-41 are 93.10 per cent, 0.012 per cent, and 6.88 per cent respectively. The isotopes of an element may be either stable or unstable (radioactive) which are subjected to decay. Radio isotope (nuclide) of any element has a chemistry identical to that of its stable isotope. Each radionuclide decays, emitting characteristic , , radiation with a characteristic half life. 5.1.0 Types of Radionuclides in the Sea The radio nuclides present in the sea can be broadly divided into three categories: 1.Long lived primary radionuclides which have existed since the formation of the planet and their short lived daughter nuclides which are continuously renewed by decay. 2.Cosmogenic radionuclides of relatively short half life which are being continuously formed by the interaction of cosmic rays with matter; and 3.Artificial radionuclides produced by human activities, such as fission products from nuclear weapons and waste products from nuclear This ebook is exclusively for this university only. Cannot be resold/distributed. power plants. 5.1.1 Long Lived Primary Radionuclides More than 90 per cent of the total radioactivity of sea water arises from 40 K (half life 1.30 × 10 9 years). For sea water of salinity 35 psu which contains 0.40 g K l –1 , the radioactivity due to 40 K is 331 pci l –1 (pico curies l – 1 ). This nuclide decays both by-emission and by K-electron capture, yielding two stable isotopes 40 Ar and 40 Ca respectively. The decay of 40 K to 40 Ar provides the basis for one of the most important geochronological methods which will be discussed later in this section. Natural rubidium (Rb) contains 27.85 per cent of radioactive 87 Rb (half life 4.7 × 10 10 years). - eBook - PDF

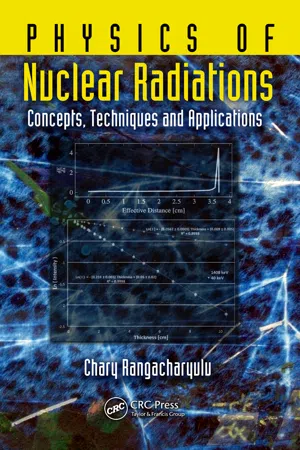

Physics of Nuclear Radiations

Concepts, Techniques and Applications

- Chary Rangacharyulu(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

2 Radioactivity 2.1 Introduction Nuclear radiations are ubiquitous. They are present in the atmosphere as cosmic rays originating in outer space, sources of which are yet un-known. They are also present in vegetation as carbon contains a small but finite radioactive isotope, 1 a fact used advantageously to determine the ages of archaeological samples. Most living beings including hu-mans contain calcium, which consists of a tiny amount of long-lived ra-dioactive potassium ( 40 K isotope). The list goes on. In the 20th century, we made significant progress in harnessing energy from nuclear fis-sion, employing nuclear techniques for non-destructive testing of ma-terials, medical diagnostics and therapy. Whether we handle radioac-tive materials for applications or we are concerned about health and safety, we need to have a good grasp of some basic terminology and be able to do simple calculations to make quantitative estimates of radi-ation phenomena. When one is concerned about radiation effects, one has to consider the species and energies of the radiations emitted and the activity levels and characteristic lifetimes of the radiation emitting sources. This chapter is devoted to radioactive levels and characteristic times. 2.1.1 Exponential Decay Law It has been found that in a sample of radioactive material, the intensity of emissions (number of emissions per unit time) decreases exponen-tially with time. Exponential growths and decays are very common in physical sciences. In the case of growth, we can specify a maximum 1 See Section 2.7. 21 22 Physics of Nuclear Radiations: Concepts, Techniques and Applications limit to which a sample, left to itself, will grow after an infinite amount of time. In the case of decay, a sample will vanish only after an infinite amount of time. 2 However, as we will see below, both growth and de-cay will be quite small after some finite time. - eBook - PDF

Radioactive Tracers in Biology

An Introduction to Tracer Methodology

- Martin D. Kamen, Louis F. Fieser, Mary Fieser(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

In general then, any element is said to be labeled if its natural isotopic content is altered. The labeling is accomplished by increasing the relative amount of a rare stable isotope or by adding a radioactive isotope. Either of these two type6 of isotopes is called a tracer. Inclusion of tracers in any aggregation of atoms of normal isotopic content produces a labeled sample of the element. Inclusion of labeled atoms in a molecule results in a labeled molecule. C. Radioactivity Types of Radioactive Decay. As stated previously, only certain com-binations of neutrons and protons are stable. An excess of one or the other component leads to a redistribution of particles during which the neutron-proton ratio is brought to the proper value for stability. This may be accomplished in several ways, for example, (1) transformation of a neutron into a proton (negative £-ray emission), (2) transformation of a proton into a neutron (positron emission or K capture), (3) emission of an a particle. In all these cases there may also be emission of elec-tromagnetic radiation in the form of y rays, x rays, etc. The emission of a particles is confined almost entirely to the heavy elements (Z > 82). Radioactivity produced artificially in the light and medium heavy ele-ments (Z < 82) is associated almost entirely with the emission of nega-tive or positive electrons. The properties of the various radiations encountered in radioactive decay will be considered in Chapter II. a. Beta Decay. The emission of negative electrons from atomic nuclei was established early in the history of radioactivity. The emission 10 RADIOACTIVE TRACERS IN BIOLOGY of positrons was discovered relatively recently. Both kinds of particles are assumed to arise during disintegration and not to be present as such in the nucleus. Positron emission differs from negative electron emission in one important respect. - eBook - PDF

- B. Zemel(Author)

- 1995(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

CHAPTER 1 RADIOACTIVITY BASICS INTRODUCTION Modern applications of radioactivity and radioactive tracers to industrial and commercial problems stem largely from the nuclear developments associated with the atomic bomb and subsequent Atoms for Peace programs in the United States and elsewhere after World War II. Successful applications of nuclear tech- nology were noted especially in the fields of medicine and oil exploration. During this time the use and development of nuclear logging tools expanded greatly. Ra- dioactive tracers were also applied to virtually every phase of oil production both in the laboratory and in the field, and small companies offering many types of ra- dioactive services proliferated. To a lesser extent, these tracer studies are still going on, most of them in the medical area. While radioactivity is certainly not a requirement for a tracer, most of the open forums devoted to tracer applications at this time are those sponsored by nuclear societies such as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the American Nuclear Society. This chapter is concerned with the basic principles and definitions required to apply radioactivity and the use of radioactive tracers to oilfield problems. This work will not cover considerations of nuclear structure or aspects of nuclear physics and chemistry that have no significant bearing on the use of radioactivity in the oil field. For readers in search of further information on these topics, many excellent references are available, a few of which are listed at the end of this chapter. We will emphasize aspects of radioactivity relevant to current oilfield practice, including some that may not be in current use but have a demonstrated utility in this area. Isotopes and nuclear structure All matter is composed of elements, which are composed of atoms. An atom consists of a small, positively charged nucleus balanced by a distribution of sur- rounding orbital electrons of negative charge. - eBook - PDF

Toxicology

Mechanisms and Analytical Methods

- C. P. Stewart, A. Stolman, C. P. Stewart, A. Stolman(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Elements which are not normally present in living tissues may be identified and perhaps even determined in this way. However, Radioactive Isotopes of elements of which the common forms are normal constituents of living matter cannot be usefully identified except in rare cases because the radioactive isotope, 12. Radioactive Isotopes AND COMPOUNDS 771 though in sufficient amount to cause toxic effects, may not affect apprecia-bly the total amount of the.element as determined chemically or physico-chemically. In these circumstances it must suffice to demonstrate the presence of radioactive matter through the effects of radiation, a method which will in any case be used even when an abnormal radioactive element is in question. Radiation detection and measurement by physical means is made possible by the ionization ability of particle emanations and gamma rays. The ionization mechanism and ion pair production rate were discussed previously. The most commonly used types of instrumentation are dosim-eters, r-meters, ionization chambers, Geiger counters, survey meters, and scintillation counters. Complete units, designed expressly for medical diagnosis, are available from a number of commercial suppliers. A. Dosimeters Dosimeters of various types and description are available from com-mercial sources. Their operation is based on the principle of the electrom-eter, which was used extensively during the early years of research with radioactive materials. The electrometer operation is illustrated in Fig. 3, > < 1 > ~ Gold Leaf Foil Calibrated Scale FIG. 3. Schematic diagram of an electrometer. which shows a metal rod extending through an insulator in a container. Two gold-leaf foils are connected to the end of the rod in the container. If a static charge is introduced onto the ball at the top of the rod, the charge will distribute itself over the rod and gold-leaf foils. The similarly charged gold-leaf foils will repel each other, as evidenced by an angular displace-ment. - eBook - PDF

- Claude J. Allègre, Christopher Sutcliffe(Authors)

- 0(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

But in 11 Isotopy each position there are several isotopes which di¡er by the number of neutrons N they con- tain, that is, by their mass.These isotopes are created during nuclear processes which are collectively referred to as nucleosynthesis and which have been taking place in the stars throughoutthehistoryofthe Universe (see Chapter 4). The isotopic composition of a chemical element is expressed either as a percentage or more convenientlyas a ratio. A reference isotope is chosen relative to which the quantities of other isotopes are expressed. Isotope ratios are expressed in terms of numbers of atoms and notofmass. For example, to study variations in the isotopic composition ofthe element strontium brought about by the radioactive decay of the isotope 87 Rb, we choose the 87 Sr/ 86 Sr isotope ratio. To study the isotopic variations of lead, we consider the 206 Pb/ 204 Pb, 207 Pb/ 204 Pb, and 208 Pb/ 204 Pb ratios. 1.3.1 The chart of the nuclides The isotopic composition of all the naturally occurring chemical elements has been deter- mined, that is, the numberof isotopes and their proportions have been identi¢ed.The¢nd- ings have been plotted as a ( Z, N) graph, that is, the number of protons against the number ofneutrons. Figure 1.3 , details ofwhich are given in the Appendix, prompts a few remarks. Firstofall,thestableisotopesfallintoaclearlyde¢nedzone,knownasthe valleyofstability because it corresponds to the minimum energy levels of nuclides. Initially this energy valley follows the diagonal Z ¼ N .Then, after N ¼ 20, the valley falls away from the diagonal on the side of a surplus of neutrons. It is as if, as Z increases, an even greater number of neutrons is neededtopreventthe electricallychargedprotons from repelling each otherandbreaking the nucleus apart.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.