Chemistry

Reaction Mechanism

A reaction mechanism is a step-by-step description of how chemical reactions occur at the molecular level. It outlines the sequence of individual chemical events that lead to the overall transformation of reactants into products. Understanding reaction mechanisms is crucial for predicting and controlling chemical reactions, as well as for designing new chemical processes and synthesizing new compounds.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Reaction Mechanism"

- eBook - PDF

- M Mortimer, P G Taylor, Lesley E Smart, Giles Clark(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Royal Society of Chemistry(Publisher)

2 3 4 6 91 As described in Section 2, a Reaction Mechanism refers to a molecular description of how reactants are converted into products during a chemical reaction. In particular, it refers to the sequence of one or more elementary steps that define the route between reactants and products. A prime objective of many kinetic investigations is the determination of Reaction Mechanism since this is not only chemically interesting in its own right, but it may also suggest ways of changing the conditions to make a reaction more efficient. There is no definite prescription for working out a mechanism and in any particular situation a solution to the problem will depend on information from a variety of sources. The behaviour of similar systems, if already established, will be an important guide and, of course, any proposed mechanism must be reasonable in terms of general chemical principles. For example, a proposed reaction intermediate, even if it cannot be detected experimentally, must still be chemically possible. One of the most important questions when dealing with Reaction Mechanism is whether or not the mechanism is composite and various kinds of evidence can often show clearly that a reaction does not occur in a single elementary step. Some of the most important forms of evidence are described below. Detection of reaction intermediates Any reaction that occurs via a series of steps will involve intermediate species; indeed the demonstration of the presence of just one reaction intermediate implies that a reaction must involve at least two steps and so must be composite. In some instances the stability of an intermediate can be sufficient to allow it to be isolated and characterized. However, more commonly, intermediates are highly reactive species and so exist in very low concentrations. If they can be detected at all, it is generally only by physical means such as some form of spectroscopy. - eBook - ePub

Survival Guide to Organic Chemistry

Bridging the Gap from General Chemistry

- Patrick E. McMahon, Bohdan B. Khomtchouk, Claes Wahlestedt(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Guide to Kineticsand ReactionMechanisms9

9.1 GENERAL CONCEPTS

9.1.1 Reaction MechanismS

- A Reaction Mechanism is an accepted sequence of elementary reaction steps which describe all (based on available information) bond-making and bond-breaking events characterizing the change of reactant molecules to product molecules.

- A reaction step (or elementary step) is the smallest observable change in molecular bonding, an individual bond-making, bond-breaking , or combination event (simultaneous bond-making and bond-breaking) that can be distinguished experimentally from other such events.

- The complete Reaction Mechanism may be composed of only one step or many steps depending on the overall (complete) reaction and the conditions.

- A Reaction Mechanism, along with the parameters that describe it such as rate, activation energies, and intermediates (described in other sections) is a path function . A path function is dependent on the “pathway” or method by which a change occurs. Regardless of the numerical value or sign of the free energy change, a reaction can occur only if there exists an available pathway by which reactant molecules can be converted into product molecules.

- Path functions must be distinguished from state functions such as ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS. These depend only on the initial and final states of the system: the total energies of the reactants versus the products. State functions do not depend on how the reaction changes occur.

- All reactants and products in a complete reaction or in a single reaction step must exist as an independent species for some measurable amount of time. This existence is due to the presence of energy barriers blocking “instant” decomposition. The compound is considered to be in a “potential energy well” (i.e., a stable energy “valley” similar to a rock sitting in a hole) termed a local energy minimum . A “deep” hole represents a very stable molecule (slow to react) because the energy barriers on each side are high. A “shallow” hole represents a relatively

- eBook - ePub

- Dov M. Gabbay, Paul Thagard, John Woods(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- North Holland(Publisher)

Gould, 1959 , p. 127]. This is what one might expect, given the explanation above of why thin mechanisms suffice for developing an understanding of organic chemistry. Second, these mechanisms break a chemical reaction down into a sequence of steps. For instance, Lowry and Richardson say: “A Reaction Mechanism is a specification, by means of a sequence of elementary chemical steps, of the detailed process by which a chemical change occurs” [Lowry and Richardson, 1987, p. 190]. These two features of mechanisms are related and both are important to the role of mechanisms in understanding chemical reactions.Providing information about the important intermediate structures in a transformation, such as the transition state or stable intermediates, allows the organic chemist to perform structural analysis of the relative energies of these intermediates. A structural analysis, in turn, enables one to predict or explain relative energy differences between structures based on a small set of robustly applicable and easily recognizable structural features. These relative energy differences can then, with the aid of the standard theoretical models of chemical transitions, be used to infer important empirically measurable features of chemical reactions such as relative rates or product distributions. 7 In this way, structural analyses of the relative energy differences between important intermediates in the course of a chemical transformation are the modern realization of Butlerov's goal to explain all the chemical properties of substances on the basis of their chemical structures. 8 - A. Kayode Coker(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Gulf Professional Publishing(Publisher)

Reaction Mechanisms and Rate Expressions 1 1 CHAPTER ONE Reaction Mechanisms and Rate Expressions INTRODUCTION The field of chemical kinetics and reaction engineering has grown over the years. New experimental techniques have been developed to follow the progress of chemical reactions and these have aided study of the fundamentals and mechanisms of chemical reactions. The availability of personal computers has enhanced the simulation of complex chemical reactions and reactor stability analysis. These activities have resulted in improved designs of industrial reactors. An increased number of industrial patents now relate to new catalysts and catalytic processes, synthetic polymers, and novel reactor designs. Lin [1] has given a comprehensive review of chemical reactions involving kinetics and mechanisms. Conventional stoichiometric equations show the reactants that take part and the products formed in a chemical reaction. However, there is no indication about what takes place during this change. A detailed description of a chemical reaction outlining each separate stage is referred to as the mechanism. Mechanisms of reactions are based on experimental data, which are seldom complete, concerning transition states and unstable intermediates. Therefore, they must to be con-tinually audited and modified as more information is obtained. Reaction steps are sometimes too complex to follow in detail. In such cases, studying the energy of a particular reaction may elucidate whether or not any intermediate reaction is produced. Energy in the form of heat must be provided to the reactants to enable the necessary bonds to be broken. The reactant molecules become activated because of their greater energy content. This change can be referred to as the activated complex or transition state, and can be represented by the curve of Figure 1-1. The complex is the least stable state through- eBook - ePub

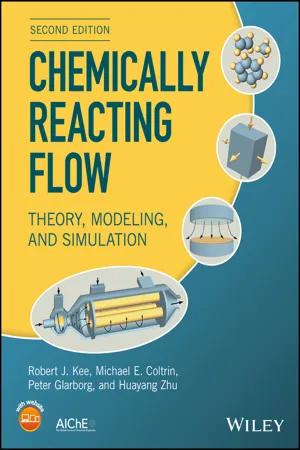

Chemically Reacting Flow

Theory, Modeling, and Simulation

- Robert J. Kee, Michael E. Coltrin, Peter Glarborg, Huayang Zhu(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

CHAPTER 14 Reaction MechanismSChapter 13 discussed the theory of elementary reactions. The chemical processes occurring in chemically reacting flows usually proceed by a series of elementary reactions, rather than by a single step. The collection of elementary reactions defining the chemical process is called the mechanism of the reaction. When rate constants are assigned to each of the elementary steps, a chemical kinetic model for the process has been developed.Using a chemical kinetic model is one way to describe the chemistry in reacting flow modeling. The chemical kinetic model offers a comprehensive description of the chemistry, but it requires a larger computational effort than simplified chemical models.The present chapter discusses the development and use of detailed Reaction Mechanisms in modeling reacting flows. Developing Reaction Mechanisms requires attention to some “collective aspects of mechanisms," such as the driving forces for gas-phase chemical processes and the characteristics and similarities of different reaction systems.For illustration, selected medium to high temperature gas-phase processes are discussed in some detail. Gas-phase reactions at elevated temperature are important in combustion, incineration, flue gas-cleaning, petrochemical processes, chemical synthesis, and materials production. Although the details of these systems may vary significantly, they share characteristics that are common for all gas-phase Reaction Mechanisms.14.1 Models for Chemistry

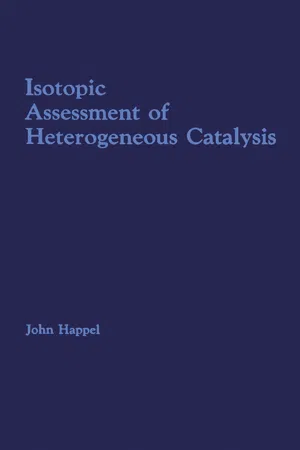

In chemically reacting flow systems, the overall reaction rate may be limited by the mixing rate of the reactants or by the rate of the chemical reaction upon mixing. If mixing is slow compared to chemical reaction, the system is diffusion or mixing controlled, while fast mixing and slow reaction results in a kinetically controlled system (Fig. 14.1 ).Figure 14.1 - John Happel(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Often thermodynamic calculations are based on taking the number of independent reactions equal to that given by Eq. 3.1. Bjornborn (1977) has reviewed the literature on this subject and shown the usefulness of restricted equilibrium calculations when the kinetics shows that the number of independent reactions is less than that predicted from the atomic matrix. It will be shown in the following development, that if we assume a knowledge of intermediates and elementary steps in addition to terminal species, it is possible not only to enumerate possible Reaction Mechanisms, but also to specify exactly the dimension of the overall reaction space without the qualifying restriction of an upper bound. In order to accomplish this we employ a method based on combinatorial principles, (Happel and Sellers, 1982, 1983). It is assumed that all elementary steps can occur in both directions for purposes of complete enumeration. Once this has been accomplished, some can be ruled out or restricted to certain ranges of operating conditions on the basis of thermodynamic or kinetic considerations. It is possible to apply the method readily by following specific examples, so only a brief general description is given here. Further details and proofs are given in the original papers, including additional examples and discussion of related procedures. 3.2 Definitions and Assumptions A Reaction Mechanism may be defined as a combination of specific elementary steps that are taken in appropriate proportions to produce the possible degrees of change of terminal species in a reacting system. Usually more elementary steps may be thought possible than those that are required to generate any single mechanism accounting for an observed overall reaction. It 3.2 Definitions and Assumptions 45 is thus necessary to consider how steps may be combined, given an appropriate initial choice of species and steps.- eBook - PDF

Fundamental Chemical Kinetics

An Explanatory Introduction to the Concepts

- M R Wright(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- Woodhead Publishing(Publisher)

Sec. 1.2] Concepts involved in modem state to state kinetics 3 For a long time chemists have used the term mechanism to refer to the chemical steps which make up a reaction. There are some reactions which occur via one chemical step only, and these are called elementary, but the vast majority of reactions proceed by two or more steps. However, in the last decade or so there has been a vast upsurge of interest in the physical mechanism of reaction. This is a description at an even more fundamental micrmcopic level than the molecular level of the chemical mechanism. A whole new field of kinetics has developed out of this interest, and the great advances in molecular beam and molecular dynamic studies reflect this interest. 1.2 Concepts involved in modem state to state kinetics State to state kinetics involves looking at the behaviour of individual molecules. These can be characterised by their quantum states which summarise information about the translational, rotational, vibrational and electronic energy of each molecule. Modern worlc looks at the processes of energy transfer which put molecules into these quantum states. It also looks at the details of reaction from these quantum states, and determines the quantum states of the products. Rate constants for these energy transfer processes and for reaction between reactants and products each in specific quantum states are detennined, and these are called state to state rate constants. This modern work relies heavily on developments in two main areas. Molecular beam experiments study the details of collisional ·energy transfer between specific quantum states, and give rates of reaction between molecules in specific quantum states. They aim at a complete physical description of what happens in a single collision, whether reactive or non-reactive. This results in a very clear description of the physical processes and mechanisms involv'ed. - eBook - PDF

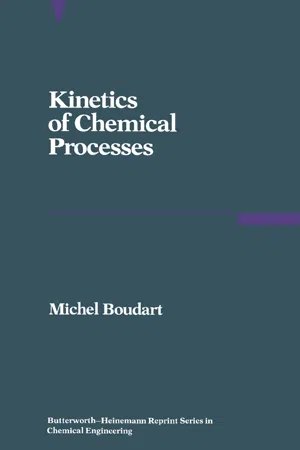

Kinetics of Chemical Processes

Butterworth-Heinemann Series in Chemical Engineering

- Michel Boudart, Howard Brenner(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

With the help of theory, the detailed 4 Introduction Chap* 1 stereochemistry of each rearrangement can then be examined and knowledge about chemical reactivity accumulated systematically. In this panoramic survey of chemical kinetics, the words mechanism or model have been excluded on purpose. Mechanism or model can mean an assumed reaction network, or a plausible sequence of steps for a given reaction, or a postulated stereochemical path during the course of an isolated step. Since methods of investigation and goals are so utterly different in the study of networks, sequences and steps, the words mechanism or model should be avoided. They have acquired the bad connotation as-sociated with irresponsible or vain speculation, largely to describe achieve-ments that vary widely in sophistication. As the reacting system evolves from reactants to products, a number of intermediates appear, reach a certain concentration and ultimately vanish. Corresponding to the distinction between networks, reactions and steps, three different kinds of intermediates can be recognized. First there are inter-mediates of reactivity, concentration and lifetime comparable to those of stable reactants and products. These intermediates are the ones that appear in the reactions of the network. A typical intermediate of this first kind is formaldehyde CH 2 0 in the oxidation of methane (see below). Then there are intermediates which appear in the sequence of steps for an individual reaction of the network. These are much more reactive than the former. They are usually present in very small concentrations and their life-time is short as compared to that of initial reactants. These reactive inter-mediates will be called active centers to distinguish them from the more stable entities which will be called intermediates for short. Typical active centers are the hydrogen and bromine atoms in the reaction between hydrogen and bromine molecules. - eBook - PDF

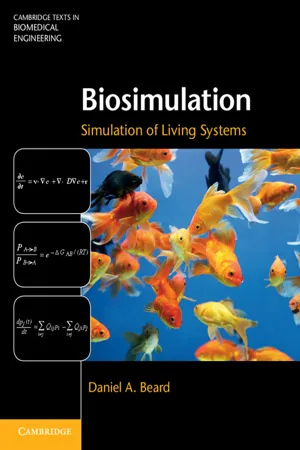

Biosimulation

Simulation of Living Systems

- Daniel A. Beard(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

6 Chemical reaction systems: kinetics Overview The fundamental physical processes of cell biology are chemical reactions and chemical transport phenomena. In any active living cell at any given time thou- sands of individual chemical transformations – oxidation of primary substrates, synthesis and replication of macromolecules, reaction-driven transport of organic and inorganic substances – are occurring spontaneously and simultaneously. To study the coordinated functions of biochemical reaction systems it will be useful to become familiar with the basics of chemical kinetics, the rules that effectively describe the turnover of individual elementary reaction steps. (Elementary reac- tions are fundamental chemical transformations that are by definition not broken down into more fundamental steps.) Elementary reaction steps can be combined to model and simulate enzymatic mechanisms catalyzing biochemical reactions. Biochemical reactions are combined in biochemical systems, networks of interde- pendent reactions. This chapter primarily treats the kinetics of individual reactions, elementary steps, and enzyme-mediated mechanisms for biochemical reactions. 6.1 Basic principles of kinetics 6.1.1 Mass-action kinetics Let us begin our study of chemical kinetics with the uni-uni-molecular reaction A J + J − B, (6.1) familiar from Chapter 5. Here we denote the rate of turnover of the reaction in the left-to-right direction (or forward flux) J + and the reverse flux J − . Therefore the net flux is given by J = J + − J − . If individual molecules in the system are kinetically isolated – i.e., the rate of transformation of an individual A molecule to a B molecule does not depend on 179 6.1 Basic principles of kinetics interactions (direct or indirect) with other A or B molecules – then the total forward flux is proportional to the number of A molecules present: J + = k + a. (6.2) Similarly, J − = k − b, (6.3) where a and b are the concentrations of A and B molecules.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.