Computer Science

Automata Theory

Automata theory is a branch of computer science that deals with abstract machines and computational processes. It explores the behavior and properties of these machines, such as finite automata, pushdown automata, and Turing machines, to understand the capabilities and limitations of computation. This theory forms the foundation for understanding formal languages, compilers, and the design of computer algorithms.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

6 Key excerpts on "Automata Theory"

- No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter 4 Automata Theory and Quantum Computer Automata Theory An example of automata and study of mathematical properties of such automata is Automata Theory In theoretical computer science, Automata Theory is the study of abstract machines and the computational problems that can be solved using these abstract machines. These abstract machines are called automata. The figure at right illustrates a finite state machine, which is one well-known variety of automaton. This automaton consists of states (represented in the figure by circles), and transitions (represented by arrows). As the automaton sees a symbol of input, it makes a transition (or jump ) to another state, according to its transition function (which takes the current state and the recent symbol as its inputs). ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Automata Theory is also closely related to formal language theory, as the automata are often classified by the class of formal languages they are able to recognize. An automaton can be a finite representation of a formal language that may be an infinite set. Automata play a major role in compiler design and parsing. Automata Following is an introductory definition of one type of automata, which attempts to help one grasp the essential concepts involved in Automata Theory. Informal description An automaton is supposed to run on some given sequence or string of inputs in discrete time steps. At each time step, an automaton gets one input that is picked up from a set of symbols or letters , which is called an alphabet . At any time, the symbols so far fed to the automaton as input form a finite sequence of symbols, which is called a word . An automaton contains a finite set of states. At each instance in time of some run, automaton is in one of its states. - eBook - PDF

Software Engineering Foundations

A Software Science Perspective

- Yingxu Wang(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Auerbach Publications(Publisher)

The latter are corresponding mainly to the flow and run-time control operations, which The 15th Law of Software Engineering Theorem 5.1 The root of computing and information science states that the most fundamental data object model shared in both computing and information science is binary digits (bits). The 15th Principle of Software Engineering Theorem 5.2 The primitive computational behaviors state that the most fundamental computational operations are logical, arithmetic, and memory access operations on bits . 284 Part II Theoretical Foundations of SE enable the algebraic composition of a large set of complex computational operations on the basis of a certain instruction set of a programming language. 5.2.2 AUTOMATA Automata are one of the earliest digital computing models that are still widely used in computing applications to model and describe system behaviors [von Neumann, 1946/58/63/66; Wiener, 1948; Shannon, 1956; Krohn and Rhodes, 1963; Arbib and Michael 1966; Arbib, 1969; Hopcroft and Ullman, 1979]. An automaton is an abstract model of computers or robots that respond to external events or stimulates by predesigned instructions. An automaton transits between a finite set of functional states driven by external events and current internal states. Therefore, it is also known as a finite state machine synonymously [Arbib et al., 1968]. In computing, automata are modeled and used mainly as finite state machines for language reorganization. However, in software engineering, automata are treated as fundamental modeling techniques of software behaviors and interactions with external environments. Therefore, an automaton can be perceived as an event-driven finite state machine. This subsection discusses the definition, formal descriptions, and applications of automata in software engineering, and their usage and limitations. - Lev D. Beklemishev(Author)

- 2000(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

Although Automata Theory has led to many results of mathematical interest, again no generally accepted system, directly useful for a theory of computation, has come forward. We think that the following quotation from WANG [1965] is still valid: “Although there are various elegant formulations of Turing machines, they are still radically different from existing computers. To approach the latter, we should use fixed word lengths, random access addresses, accumu- lator, and permit internal modifications of the programs. Alternatively, we could, for example, modify computers to allow more flexibility in word lengths. Too much energy has been spent on oversimplified models, so that a theory of machines and a theory of computation which have extensive practical applications have not been born yet.” We shall give here a few examples of several automaton-like models that have been proposed in the past few years. No attempt is made at complete- ness, but we wish to give only an impression of the great variety that exists in this field: bl. One of the first proposals was made by KAPHENGST [1959]. This paper introduces concepts such as register, instruction and instruction counter, etc., in an abstract machine which is then proved to be equivalent to recursive functions. b2. A paper by RAYMOND [1966]. Emphasis is laid here upon a study of the memory of a computer. b3. A paper by DE BACKER and VER~EEK [1966]. In this article the notion of error in a computation plays an important role. b4. A paper by MAURER [1966]. This paper covers many aspects of existing computers : It treats the notions of memory, registers, input/output, and instructions. It appears to be an interesting contribution to a theory of computing that is more concerned with hardware aspects. b5. The stack automata, as introduced by GINSBURG, GREIBACH and HARRISON [1967]. Here the purpose is to simulate techniques which are used in the translation of programming languages.- eBook - PDF

- Murray Muraskin, F Brody, Tibor Vamos(Authors)

- 1995(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

That is, if A can produce B, then A in some way must have contained a complete description of B. In order to make it effective, there must be, furthermore, various arrangements in A that see to it that this description is interpreted and that the constructive operations that it calls for are carried out. In this sense, it would therefore seem that a certain degenerating tendency must be expected, some decrease in complexity as one automaton makes another automaton. Although this has some indefinite plausibility to it, it is in clear contradiction with the most obvious things that go on in nature. Organisms reproduce themselves, that is, they produce new organisms with no decrease in complexity. In addition, there are long periods of evolution during which the complexity is even increasing. Organisms are indirectly derived from others which had lower complexity. Thus there exists an apparent conflict of* plausibility and evidence, if nothing worse. In view of this, it seems worth while to try to see whether there is anything involved here which can be formulated rigorously. So far I have been rather vague and confusing, and not uninten-tionally at that. It seems to me that it is otherwise impossible to give a fair impression of the situation that exists here. Let me now try to become specific. Computers 551 4 1 6 Natural and Artificial Automata GENERAL AND LOGICAL THEORY OF AUTOMATA Tarings Theory of Computing Automata. The English logician, Turing, about twelve years ago attacked the following problem. He wanted to give a general definition of what is meant by a com-puting automaton. The formal definition came out as follows: An automaton is a black box, which will not be described in detail but is expected to have the following attributes. It possesses a finite number of states, which need be prima facie characterized only by stating their number, say n, and by enumerating them accordingly: 1, 2, • • • n. - eBook - PDF

Foundations of Mathematical Biology

Cellular Systems

- Robert J. Rosen(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Academic Press(Publisher)

Clearly these aspects are not independent. We have already mentioned the work of Cowan and Winograd on combatting computation errors in automata, by applying information and coding theory to the problem. A major task for our theory is to learn how to apply coding theory to the prob-lem of enduring and multiplying in the presence of noise. We already have suggested that Automata Theory may help refine theoretical biology by allow-ing us to completely describe systems that share more and more of the properties we ascribe to living systems, so that we may avoid oversimplifica-tions which are almost inevitable at the level of verbal discourse. Let us now note that our strategy may be a fruitful one, whether or not one holds the reductionist view that all vital processes can be reduced to physicochemical 208 Michael Α. Arbib terms, that is, whether one believes that one is converging to an understanding of the nature of life, or sharpening an inevitable distinction between living things and man-made machines. I personally believe reduction is possible, but cannot share the confidence expressed by Crick [1966] in its imminence, since I believe that we are at the very beginning, and require immense break throughs in the mathematical theory of automata and other complex systems, before we can hope really to understand the hierarchy of processes that extends from molecule to man. It seems to me that the notion of DNA —> RNA —> enzyme transduction is of as vital importance to understanding life as the conversion of decimal numbers to binary notation is to understanding digital computers. However, just as computers may be built to operate in a nonbinary mode, so may there be life without DNA; and we are no more entitled to say we understand embryology when we understand DNA than we are entitled to say we understand computation when we understand radix two. Perhaps our automaton models may break us of too parochial a view of the goals of theoretical biology. - eBook - PDF

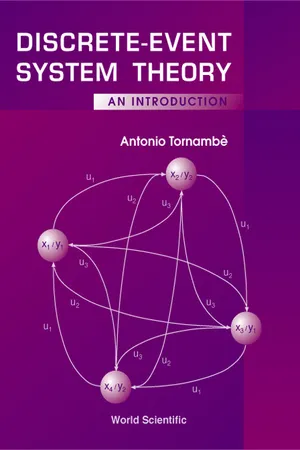

Discrete-Event System Theory

An Introduction

- A Tornamb??(Author)

- 1995(Publication Date)

- WSPC(Publisher)

Chapter 2 Automata's theory: an algebraic approach This chapter is an introduction to the algebraic structure of automata. A collection of examples is included to illustrate the algebraic principles and methods of automata } s theory. Section 2.1 (Equivalence between completely-specified automata) is an extensive study — by means of a formal presentation of definitions, of problems and of the corresponding solutions — of the theory of completely-specified automata, with emphasis on the following topics: state-equivalence between states, state-equivalence between automata, completely-specified au-tomaton in reduced form, input-output function of a completely-specified automaton, In-equivalence between states and automata. Nonetheless, Section 2.1 contains techniques for the computation of an automaton in reduced form. Section 2.2 (Inclusion between partially-specified automata) is an extensive study — by means of a formal presentation of definitions, of problems and of the corresponding solutions — of the theory of partially-specified automata, with emphasis on the following topics: in-cluded states, included automata, partially-specified automata in reduced form, input-output function of a partially-specified automaton. Section 2.3 (Automata and semigroups) points out the relationship between semigroups and automata, reporting some notions, such as: ordinary simple experiment, branching simple experiment, ordinary multiple experiment, branching multiple experiment, initial-state detectable automaton, observable automaton, homomorphism of automata, simulation of au-tomata. Section 2.4 (Exercises with solutions) contains numerous exercises, which are provided with the corresponding solutions, depicting the algebraic behaviour of automata. A careful study of these exercises will develop the type of intuition that should allow the reader to become familiar at an elementary level with automata.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.