Geography

Earthquake Hazard Management

Earthquake hazard management involves the assessment, mitigation, and response to the risks posed by earthquakes. It encompasses measures such as land-use planning, building codes, public education, and emergency preparedness to minimize the impact of earthquakes on human populations and infrastructure. Effective earthquake hazard management aims to reduce the potential for loss of life and property damage associated with seismic events.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

11 Key excerpts on "Earthquake Hazard Management"

- Tanjina Nur(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Arcler Press(Publisher)

There is no motivation to dismiss every single such claim as the rantings of individuals who recently suffered a remarkable earthquake. In few cases, individuals had effectively pointed out such phenomena previously the earthquake struck. However, such encounters did not support in making forecasts for the earthquakes (Figure 6.1). Earthquake Management and Mitigation 145 Figure 6.1. Earthquake management during disaster. Source: https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/news/2017-9-7-disaster-man -agement-in-nepal-laws-in-the-Making-DFID.png Thus, there prevailed a pessimistic view about earthquakes, one that saw them as among the numerous definitely unpredictable forces of nature. It is difficult to settle on informed decisions as to dealing with the hazard related with any danger unless the hazard is first comprehended. Simply expressed, hazard is the result of the likelihood that an event of a given seriousness will be experienced and the probable outcomes of that occasion should it happen. Risk associated with the peril may be represented in various ways including: • The possibility that losses occurred to a mentioned danger will be surpass a specified amount in a provided period of time; • The average yearly overall loss comprising all disastrous events that could occur; and • The maximized final loss that could happen, provided that a significant level of deleterious event is experienced. Misfortunes in terms of losses can be communicated in a few forms, includ-ing death toll and monetary loss. The most ideal approach to express these different losses relies upon the decision model that the risk manager likes to use in settling on alternative risk mitigation approaches. For risk related to earthquake, two measures of risk are likely generally suitable. The first of these is the scenario-based estimation. In this approach, a particular earthquake is assumed to happen, and the potential losses from this occasion are evaluated.- eBook - ePub

Integrating Disaster Science and Management

Global Case Studies in Mitigation and Recovery

- Pijush Samui, Dookie Kim, Chandan Ghosh(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Elsevier(Publisher)

Chapter 2Importance of Geological Studies in Earthquake Hazard Assessment

Biju John National Institute of Rock Mechanics, Kolar Gold Fields, IndiaAbstract

Earthquake hazard assessment, fundamentally an attempt to forecast the likelihood and effects of earthquakes in years to come, is analogous to long-term earthquake prediction. An assessment of the earthquake hazard for a location of interest is a prerequisite for any development activities. Historical record of earthquake occurrence, together with the instrumental seismographic records, forms an invaluable data set for evaluating the long-term seismic potential for a particular site of interest. However, in most cases, these data sets are not sufficient for long-term representatives of seismicity.Large earthquakes generally leave clues about them in the rocks and the landforms. To read the past seismic information, geologists use an integrated approach comprising geomorphology, structural geology, geochronology, sedimentology, pedology, etc. Through a meticulous evaluation of fault-related geological information, displacement per event, return period, and magnitude can be estimated.The geological formations and their geotechnical properties along with the source distance will determine the variations of ground shaking in space, amplitude, frequency content, and duration during an earthquake for a given site. The strong ground shaking is also modified by lithology and lateral geological discontinuities. Thus, understanding the nature of local geological formation is the basis for demarcating different levels of hazard zones for development activities.Keywords

active faults paleoseismology seismic microzonation seismic potential seismotectonic evaluation2.1. Introduction

Earthquakes lead the list of natural disasters in terms of damage and human loss and they affect very large areas, causing death and destruction on a massive scale. Seismicity of any region depends on the state of tectonic stress across structural discontinuities/faults, which are remarkably different when comparing interplate and intraplate settings. The return period of damaging earthquakes are much shorter in interpolate regions compared to intraplate settings. The Indian landmass, having plate boundaries and intraplate settings, has generated a large number of destructive earthquakes in the recent past (Rajendran and Rajendran, 2004 - eBook - ePub

The Distributed Functions of Emergency Management and Homeland Security

An Assessment of Professions Involved in Response to Disasters and Terrorist Attacks

- David A. McEntire(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Notably, hazards geography and land use management originated within this tradition. As described by Susan Cutter, a distinguished geographer at the University of South Carolina, hazard geographers focus on addressing four key questions: 1) how many people are located in hazardous areas, 2) how do people respond to hazards and what factors contribute to these responses, 3) what can be done to mitigate hazards and risks at a particular location, and 4) are people and places becoming increasingly vulnerable to hazards? (Cutter, 1996, p. 529). Geography programs at the university level have experienced increased interest in courses related to environmental and human-made hazards, with many courses examining topics such as sources of hazards, hazard adjustments, and the human-ecological dimensions of hazards (Cross, 2000). Within this tradition, geographers utilize the geographic methods discussed earlier to examine the intersection of hazards, people, and the built environment (Montz and Tobin, 2010). Hazards-related curriculum coupled with courses pertaining to geographic methods provide students with the knowledge and skill sets to carry out key functions in emergency management and homeland security. Because of this, the human-environment tradition is closely related to the emergency management and homeland security fields, it is not uncommon to see graduates of geography programs employed in various emergency management and homeland security capacities at the local, state, and federal levels. Specifically, geographers in these fields are often responsible for conducting hazard identification and risk assessments, mitigation planning and strategy implementation, and social demographic studies that inform vulnerability assessments - Judith Rosales(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Delve Publishing(Publisher)

64 3.2 Steps Prescribed by Federal Emergency Management Agency to be Taken For Earthquake Management ....................................... 73 3.3 Conclusion ........................................................................................ 85 3.4 Case Study ......................................................................................... 85 References ............................................................................................... 91 “We cannot stop natural disasters but we can arm ourselves with knowledge: so many lives would not have to be lost if there was enough disaster preparedness.” — Petra Nemcova Disaster Management of Earthquakes & Volcanoes 64 Disasters may take place in different forms. Their occurrence is the most unfortunate happenings that can take place with the mankind and other organisms. The damage, destruction, and threats that disaster brings with itself are incomparable and have a vast outreach. One such disaster and the most common and destructive of them is an “‘earthquake”. An earthquake may result in loss of livelihood and properties and prove to be massively destructing. Hence, a need was felt by some of the agencies that aim at safety and security from an earthquake, to establish guidelines that may be followed by the individuals during and even before and after the crisis, so as to prevent the heavy losses that are frequently incurred due to such disasters. This chapter enlists the same guidelines, for the readers to understand the importance of having such guidelines and follow them if they, unfortunately, land themselves in a crisis such as this. 3.1 THE NEED AND IMPLEMENTATION OF GUIDELINES There should be the presence of a proper set of guidelines that make the safety program of a community of people, corresponding to any of their habitat like the nation, state, city, or village, effective.- eBook - PDF

- F G Bell(Author)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- Butterworth-Heinemann(Publisher)

Geological hazards can be responsible for devastating large areas of the land surface and so can pose serious constraints on development. However, geological processes such as volcanic eruptions, earthquakes, landslides and floods cause disasters only when they impinge upon people or their activities. Even so, as the global population increases, the significance of geohazards is likely to rise. In terms of financial implications, it has been esti-mated that natural hazards cost the global economy over $50,000 million per year. Two thirds of this sum is accounted for by damage, and the remainder represents the cost of predicting, preventing and mitigating against disasters. Geological hazards vary in their nature and can be complex. One type of hazard, for exam-ple, an earthquake, can be responsible for the generation of others such as liquefaction of sandy or silty soils, landslides or tsunamis. Certain hazards such as earthquakes and land-slides are rapid onset hazards and so give rise to sudden impacts. Others such as soil erosion and subsidence due to the abstraction of groundwater may take place gradually over an appreciable period of time. Furthermore, the effects of natural geohazards may be difficult to separate from those attributable to human influence. In fact, modification of nature by humans often increases the frequency and severity of natural geohazards, and, at the same time, these increase the threats to human occupancy. The development of planning policies for dealing with geohazards requires an assessment of the severity, extent and frequency of the geohazard in order to evaluate the degree of risk. The elements at risk are life, property, possessions and the environment. Risk involves quan-tification of the probability that a hazard will be harmful, and the tolerable degree of risk depends on what is being risked, life being much more important than property. - eBook - PDF

Earthquake Research and Analysis

Statistical Studies, Observations and Planning

- Sebastiano D'Amico(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

The planning made in the regions with high earthquake risk should be supported by identifying with the probable earthquake scenarios. In earthquake sensitive planning, the formation of gradual centers system with one main center, the identification of the intensities in correlation with settlement potential, the development of multicentered urban form by preventing urban sprawl are essential. In the urban areas with high earthquake risk, the improvement of the current plans, the reconfiguration in the required locations and the planning of development areas based on the microzoning maps and probable earthquake scenarios would decrease the probable earthquake damages. In earthquake sensitive planning, the integration of geotechnical parameters of the soil as soil amplification, liquefaction and landslide after evaluation to the planning is of vital importance since these parameters during an earthquake can cause secondary urban risks. The main factors effective in the distribution of earthquake damage can be summarized as the distance of the settlement to the active fault line, geological structure, local soil conditions, the state of ground water, site selection and land use, population density and distribution, building density, quality, order and design. As it is seen, the basis of creating a safe and sustainable living space in the urban settlement areas with high seismic risk is the evaluation of urban planning and design, geological synthesis and earthquake analysis in coordination with modern scientific methods and techniques. Correlation Between Geology, Earthquake and Urban Planning 433 8. References Dai F. C., Lee C. F., Zhang X. H. (2001) GIS based geo-environmental evaluation for urban land-use planning: a case study, Engineering Geology, 61, 257-271. Darvishsefan A. A., Setoodeh A., Makhdom M. (2004) Environmental consideration in railway route selection with GIS (Case study: Rasht-Anzali railway in İ ran), Map Asia 2004, Beijing, China. - eBook - ePub

- Luis Gonzalez de Vallejo, Mercedes Ferrer(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

ISDR, 2009 ).One of the main aims of engineering geology , as a science applied to the study and solution of problems produced by the interaction of the geological environment and human activity, is the evaluation, prevention and mitigation of geological risks, i.e. of the damage caused by geodynamic processes.The problems arising from the interaction between human activities and the geological environment make appropriate actions to balance natural conditions and land use, with geological hazard prevention and mitigation methods essential at the planning stage. These actions should have as their starting point an understanding of geodynamic processes and of the geomechanical behaviour of the ground.The damage related to a specific geological process depends on:— The speed, magnitude and extent of the process; geological hazards may be violent and catastrophic (earthquake, sudden large-scale landslide, collapse) or slow (flows and other slope movements, subsidence, etc.).— The chances for prevention or prediction and the warning time available; some processes, such as earthquakes or flash floods, cannot be forecast, and they give very little warning time or none at all.— Whether actions can be taken to control the process or protect elements exposed to its effects.The effects of ground movements may be direct or indirect, short or long term or permanent. Some tectonic or isostatic processes develop on a geological time scale, what means that their effects cannot be considered on a human scale.Only certain processes, when they occur on an “engineering” or “geotechnical” scale, can be controlled - eBook - PDF

- Arvin Farid(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

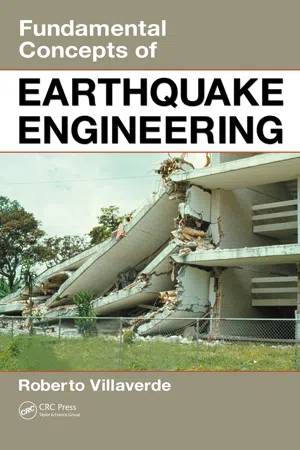

Introduction Geohazards (GHZs) are defined as geological (geotechnical, hydrogeological) states that may lead to widespread damage or risk. They are geological and environmental conditions involving long‐term or short‐term geological processes. Humans are also altering the planet © 2016 The Author(s). Licensee InTech. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. with actions, traceable back to the Neolithic age agriculture. We can call these interactions between the geosphere and humanity Anthropogenic (ANPgenic) global changes. As we can safely assume we are in the Anthropocene (ANPcene), it is also safe to assume that many of the processes we observe nowadays are man‐made or man‐altered. It is therefore obvious that risks and crises, hazard and risk perception and related decision‐making, loaded with their social aspects, have to be studied in a holistic way, integrating humanistic and social aspects to rational, technical, and scientific approaches. Human‐generated, i.e., man‐made or man‐altered, GHZs and natural‐occurring GHZs lists can be, in first analysis, assumed to be identical. That applies even to seismicity as lately exposed by research on fracking and other oil‐extraction techniques. Exceptions are special hazards like the spread of unexploded landmines contamination via erosion and flooding processes, the spread of heavy metals or other contaminants via dumps leaching or mining tailings, dam failures, etc. This chapter focuses attention on the “damage and risk side” of the phenomena rather than on its generating processes or on the full risk assessment/management (RA, RM) process: GHZ processes may hit targets T with a probability p and generate damages (losses) or consequen‐ ces, C. - Roberto Villaverde(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

As a result, the objective of a seismic hazard assessment in the past has been, and still is, an estimation of the peak ground acceleration, peak ground velocity, or response spectrum ordinates of the ground motions expected at a given site as a result of the earthquakes that can be generated, within a given time interval, in the vicinity of the site. Thus, in general terms, an assessment of the seismic hazard at a specific site involves the following steps: 1. Identification and characterization of all earthquake sources capable of producing signifi-cant ground motions at the site 2. Estimation of the magnitude and the frequency of the earthquakes that can be generated at these sources 3. Evaluation of the distance and orientation of each source with respect to the site 4. Establishment of statistical correlations between earthquake magnitude, earthquake source characteristics, distance from source to site, and ground motion intensity (e.g., peak ground acceleration, peak ground velocity, or response spectrum ordinates) 5. Estimation of the expected ground motion intensity at the site using these correlations in terms of (a) the expected earthquake magnitudes at the identified sources, (b) the known characteristics of these sources, and (c) the estimated distances from the sources to the site There are obviously several ways by which such an assessment can be made. In the early days of earthquake engineering, it was made deterministically without due consideration of all the uncertainties involved in the evaluation process and the fact that earthquakes are, for the most part, random events. That is, an assessment of the seismic hazard at a particular site was made by assuming the occurrence of an earthquake of a presumed possible largest magnitude at a nearby, previously known, earthquake fault. Today, these assessments are invariably made, explicitly or implicitly, within a probabilistic framework.- eBook - PDF

Geotechnical Risk and Safety

Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium on Geotechnical Safety and Risk (IS-Gifu 2009) 11-12 June, 2009, Gifu, Japan - IS-Gifu2009

- Yusuke Honjo, Makoto Suzuki, Takashi Hara, Feng Zhang, Yusuke Honjo, Makoto Suzuki, Takashi Hara, Feng Zhang(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Geotechnical Risk and Safety – Honjo et al. (eds) © 2009 Taylor & Francis Group, London, ISBN 978-0-415-49874-6 Risk assessment and management for geohazards F. Nadim International Centre for Geohazards (ICG) / Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI), Oslo, Norway ABSTRACT: Each year, natural disasters cause countless deaths and formidable damage to infrastructure and the environment. In 2004–5, more than 300,000 people lost their lives in natural disasters. Material damage was estimated at USD 300 billion. Many lives could have been saved if more had been known about the risks and possible risk mitigation measures. The paper summarizes the state-of-the-art in the assessment of hazard and risk associated with landslides, earthquakes and tsunamis. The role of such assessments in a risk management context is discussed and general recommendations for identification and implementation of appropriate risk mitigation strategies are provided. 1 INTRODUCTION “Geohazards”, i.e. natural hazards that are driven by geological features and processes, pose severe threats to humans, property and the natural and built environ-ment. During 2005, geohazards accounted for about 100,000 deaths worldwide, of which 84% were due to October’s Pakistan earthquake. In that year, natural disasters affected 161 million people and cost around US$ 160 billion – over double the decade’s annual aver-age. Hurricane Katrina accounted for three quarters of this cost. During the period 1996 to 2005, natural dis-asters caused nearly one million lives lost, or double the figure for the previous decade, affecting 2.5 bil-lion people across the globe (World Disaster Report, 2006). - eBook - ePub

Engineering Geology

Proceedings of the 30th International Geological Congress, Volume 23

- Wang Sijing, Marinos(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

City dwellers are not helpless, however, facing the natural and natural-anthropogenic hazards. Studying natural conditions and close cooperation between architects, designers, planners, geologists and engineers assists in solving many issues of rational urban land-use and urban stability providing.The World Conference on Natural Disaster Reduction (held in the city Yokohama in 1994), elaborated a new concept based on forecast of the timely preparedness to natural disasters [16] . This new concept concerns the disaster response as a compelling limited measure, which does not solve the problem as a whole, but yields only temporary results at a very high cost. As regards urban areas, the main constituents of this new concept are as follows: engineering-geological zonation of urban areas; monitoring and prediction of hazardous phenomena; making timely decisions on management.Engineering-geological zonation

The engineering-geological zonation of the city area is one of the most important measure in mitigating the risk from natural and natural-anthropogenic disasters. The zonation should be executed by a number of geological factors: relief, rock composition and properties, hydrogeological conditions geodynamical-process development, etc. In the maps of engineering-geological zonation the urban area is divided into zones according to land-use fitness and stability to natural and natural-anphropogenic impacts. This zonation contributes to making appropriate planning decisions and to optimal investments in urban-land development meeting safety requirements.The seismic-microzonation maps are complied for seismicity-prone regions besides the maps of engineering-geological zonation. The main objective of these maps is subdivision of the city area by the seismic-hazard level (earthquake magnitude) with account of all specific factors, influencing on spreading the elastic waves in geological environment.Monitoring and forecast

Possible changes in urban geoenviroment should be taken into account during carrying out the planning and constructing activities. This requires the constant control over the urban geoenvironment by means of the monitoring system. The objects of monitoring are specific in every city, depending on geologic, geomorphologic, climatic and other conditions. The database and observation rows are compiled on the base of constantly replenished monitoring information, which are then processed in accordance with the tasks set. The alteration regularities (trends) in objects (processes) under monitoring are further find out to forecast the hazard development.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.