History

Labor Unions Gilded Age

During the Gilded Age, labor unions emerged as a response to poor working conditions, low wages, and long hours in industrial workplaces. These unions sought to improve the lives of workers through collective bargaining, strikes, and advocacy for labor rights. Despite facing opposition from employers and the government, labor unions played a significant role in shaping labor laws and improving working conditions for many Americans.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Labor Unions Gilded Age"

- eBook - ePub

Dissent

The History of an American Idea

- Ralph Young(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- NYU Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 12Workers of the World Unite!

Workingmen, to Arms!!!! . . . You have for years endured the most abject humiliations; . . . you have worked yourself to death; . . . your Children you have sacrificed to the factory lord—. . . you have been miserable and obedient slaves all these years. Why? To satisfy the insatiable greed, to fill the coffers of your lazy thieving master? When you ask them now to lessen your burdens, he sends his bloodhounds out to shoot you, kill you! . . . To arms we call you, to arms!—August Spies, summoning workers to a rally at Haymarket Square, May 4, 1886The Gilded Age was an era of unprecedented industrial and urban growth, a time of seemingly unlimited expansion of American business. The timber, iron ore, precious metals, and agricultural products from the West were a boon to the economy. Cornelius Vanderbilt, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, J. P. Morgan, and other entrepreneurs created huge monopolies and trusts and seemed to wield more power than the federal government itself. Inventions such as the electric light, the telephone, and the electrification of urban mass-transit systems, as well as innovations such as mass marketing, professional spectator sports, and department stores, transformed daily life.But as the cities grew and the nation rapidly industrialized, so too did serious problems. Political corruption ran rampant in the cities. Unscrupulous employers and landlords took advantage of the poor and the new immigrants flooding in from Europe. Workers had little choice but to take jobs in unsafe factories and industrial plants where they barely earned enough to support themselves. Appalling working and living conditions led to mounting discontent. Discontent led to dissent. Dissent led to activism. Activist workers organized and showed a willingness to go on strike. They called for owners to recognize and negotiate with their unions, and they demanded a living wage and a safe working environment, while farmers, as we have seen, also organized cooperatives and a political party to push for their interests. By the 1890s it seemed that workers and farmers were on the brink of forming an extensive radical coalition that would force the government to address their concerns, recognize their contribution to American prosperity, alleviate their suffering, and protect their rights. - William E. Forbath, William E. FORBATH(Authors)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

J. of Soc. 164 (1979). 12 Law and the Shaping of the American Labor Movement The new labor history undermines another old assumption by showing that the mutualism that organized workers displayed at work frequently carried over into their communities and their political lives. In the older accounts of the nineteenth-century labor move- ment, the voices of radical politics and broad reform ambitions are those of meddling middle-class politicians, marginal intellectuals, and professional reformers and "agitators."5 The bulk of real trade unionists, so the story goes, were committed to "trade unionism pure and simple." In actuality, however, most Gilded Age trade unionists were steeped in labor politics and reform, and most re- formers were active trade unionists. 6 The Gilded Age's leading labor journalist, John Swinton, expressed a majority view when he pro- claimed, "there is a world in the belly of the ballot." "All the enginery of power" lies there. 7 The largest and most influential of Gilded Age labor organizations was the Knights of Labor, whose active membership in the 1880s numbered almost one million. 8 The Knights exemplified Gilded Age workers' melding of trade union and political endeavors as well as 5. See, e.g., S. Perlman, A Theory of the Labor Movement; S. Perlman, The History of Trade Unionism in the United States (1922); 2 J. Commons et aI., History of Labour in the United States (1935); G. Grob, Workers and Utopia (1961). 6. See D. Montgomery, Beyond Equality: Labor and the Radical Republicans, 1862- 1873 (1967); L. Fink, Workingmen's Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics (1983) [hereinafter, L. Fink, Workingmen's Democracy]; S. Ross, Workers on the Edge: Class, Community, and Politics in Cincinnati (1986); F.- eBook - ePub

Class and the Making of American Literature

Created Unequal

- Andrew Lawson(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

within these groups become more intensive. In aggregate, labor problem novels can be understood as a literary dimension of class formation with both a class expressive and formative role. In short, labor problem stories variously mapped current class relations in formation, contained assessments of how collective actions (e.g., strikes, unions, and militias) were performed, provided evaluative status of class character, and offered blueprints for social change to remedy the labor problem ushered in by industrial capitalism.POLITICAL ECONOMY, CLASS, AND LABOR MOVEMENT

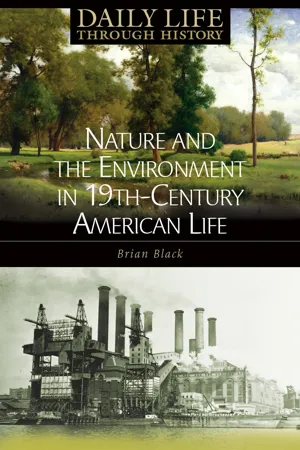

The Gilded Age was a major turning point in the development of the U.S. political economy, marking the rise of industrial capitalism, the rise of a national-level labor movement, and a major shift in the relations and meanings of social class. The United States experienced an enormous surge toward industrial capitalism, the appearance of huge economic enterprises, a transition from proprietary to corporate capitalism, an increasing shift from rural to urban society, and the emergence of new social classes. By the mid-1870s, industrial capital grew and so, too, did the working-class. Economic inequality widened as a consequence. The labor movement grew in size, formed around modern notions of class rooted in wage labor. Signs of cross-trade working-class fraternalism began to appear in labor journals like the Workingman’s Advocate, National Labor Tribune , and others by the early Gilded Age (Montgomery, Beyond ).Cultural boundaries between capital and labor hardened with greater between-class social distance and greater within-class solidarity. Collective action in the labor movement field became much more contentious and lethal (Lipold and Isaac), and the decades of the Gilded Age were repeatedly punctuated with a series of major class struggle flashpoints such as the general strike of 1877 and the Chicago Haymarket Riot of 1886, which served to construct a new political-cultural context. As Reconstruction fizzled and Jim Crow was established across the South, the central issue of the day became the “labor problem” or “labor question.” That problem reached crisis levels and permeated general discourse and all forms of cultural media, including realist fiction. - Brian C. Black(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- Greenwood(Publisher)

Overall, the expanding economy of the late nineteenth century was ripe for development by those with foresight and an aggressive approach to business. However, the new era of industry clearly created a distinct working class. The ethics with which the few successful tycoons managed their workforces are considered extremely dubious by today’s standards. During the Gilded Age, many capitalists dismissed considerations of workplace safety and human welfare in order to create the greatest possible profits. For instance, child labor became a norm in factories, mines, and other extremely dangerous environments, largely because children required the least pay. All industrial growth surged after the Civil War. This growth and a general faith in economic development allowed a few corporations to gain control of entire commodities and their production. Called trusts, these conglomerates were near monopolies during an era when government and society had not yet defined such an entity as evil. With such power reform faced a mighty plifying production tasks and la concentrated in a single entity, any efforts for challenge. Against a culture in which these ethics were the norm, a younger gener- ation came of age in the 1890s and began to demand reform. Initially, one of the most common outlets for voicing discontent was journalism. The impassioned pleas of concerned journalists, then, found receptive ears among the elite women of the era. Activists such as Jacob Riis, who wrote How the Other Half Lives in 1890 to describe life in New York City slums, and Jane Addams, who started Hull House to aid immigrant acclimation to American culture, led a movement for progressive reform. Ironically, the wealth of some robber barons would contribute to the evolution of a public consciousness on issues such as ghettos, environmental degradation, and unfair labor practices.- Gregory Feldmeth, Christine Custred, Christine Custred(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Research & Education Association(Publisher)

Industrial expansion and technology assumed major proportions in this period. Between 1860 and 1894 the United States moved from being the fourth-largest manufacturing nation to the world’s leader through capital accumulation, natural resources (especially iron, oil, and coal), an abundance of labor helped by massive immigration, railway transportation and communications (the telephone was introduced by Alexander Graham Bell in 1876), and major technical innovations, such as the development of the modern steel industry by Andrew Carnegie and electrical energy by Thomas Edison. In the petroleum industry, John D. Rockefeller controlled 95 percent of U.S. oil refineries by 1877.The New SouthBy 1880, Northern capital erected the modern textile industry in the New South by bringing factories to the cotton fields. Birmingham, Alabama, emerged as the South’s leading steel producer, and the introduction of machine-made cigarettes propelled the Duke family to prominence as tobacco producers.Social DarwinismThe theory of Social Darwinism, which asserted that survival of the fittest applied in society as well as nature, gained popularity in the Gilded Age. Many industrial leaders used the doctrines associated with the “Gospel of Wealth” to justify the unequal distribution of national wealth. Self-justification by the wealthy was based on the notion that God had granted wealth to a select few. These few, according to William Graham Sumner, relied heavily on the teachings of Charles Darwin.Labor UnrestWhen capital overexpansion and overspeculation led to the economic panic of 1873, massive labor disorders spread through the country leading to the paralyzing railroad strike of 1877. Unemployment and salary reductions caused major labor conflicts. President Hayes used federal troops to restore order after dozens of workers were killed. Immigrant workers began fighting among themselves in California where Irish and Chinese laborers fought for economic survival.Labor UnionsThe depression of the 1870s weakened national labor organizations. The National Labor Union (1866) had a membership of 600,000, but failed to withstand the impact of economic adversity. The Knights of Labor (1869) managed to open its membership to immigrants, women, and African Americans, in addition to white native American workers. Although they claimed one million members, they too could not endure the hard times of the 1870s, and eventually went under in 1886 in the wake of the bloody Haymarket Riot in Chicago.- eBook - ePub

Tramps and Trade Union Travelers

Internal Migration and Organized Labor in Gilded Age America, 1870–1900

- Kim Moody(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Haymarket Books(Publisher)

Although perhaps diminished in numbers, the labor press was a central piece of the working-class “culture of opposition” that survived into the early twentieth century. It provides not only the evidence for a developing class consciousness throughout the Gilded Age, but also was, in fact, a major shaper of that consciousness and much of its content. One finds there not only news, but political advocacy, international labor developments, and the ideas of Ira Steward and the many nameless autodidacts who rejected the wage-fund theory, the inevitability of supply and demand, the authority of capital over the lives of the wage-earning class, and indeed for many the wage-system itself.Working-Class Culture in the 1890s

The standard narrative of labor’s development in the 1890s was that of a “rightward drift,” the emergence of “prudential” unionism in the AFL, and the dominance of “pure and simple” unionism.114 With the decline of the Knights, much of the visible “culture of opposition” described by Oestreicher also declined or altered by the end of the 1880s. Yet, as even Oestreicher argues in his conclusion, “Despite that destruction [of the Knights], the events of the 1880s left a legacy. Even without the framework of a unifying organization like the Knights of Labor, the memories of the 1880s were repeatedly sufficient to bring workers into the streets in the 1890s.” Perhaps even more important, he wrote, “The cooperative work traditions, the spirit of mutuality that lay at the heart of the subculture of opposition continued.”115 - eBook - ePub

Barons of Labor

The San Francisco Building Trades and Union Power in the Progressive Era

- Michael Kazin(Author)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- University of Illinois Press(Publisher)

2Like most union leaders in the Progressive era, BTC leaders were professionals. While the typical union official in the nineteenth century had been an impoverished missionary who traveled from city to city preaching the faith and signing up converts, his successors were likely to be homeowning urbanites with a staff of assistants well versed in the techniques of collective bargaining. A heroic national figure like Peter J. McGuire who irregularly collected his weekly salary of $15 while he organized the Carpenters’ Union in the 1880s gave way to such careerists as George L. Berry of the Printing Pressmen who died in 1948 with an estate worth $750,000.3In San Francisco, this transformation occurred quite swiftly—from 1895 to 1905. The temporary locals and paper councils of the Gilded Age had been led by volunteers whose only income came from their craft and who usually depended on individual members rather than paid business agents to enforce union rules. In 1886, Frank Roney, the first president of the Federated Trades Council, considered himself supremely fortunate when, black-balled from his job as a foundry foreman, he used a political connection to secure·a fireman’s job at city hall. There, his boss, a former union seaman, allowed Roney to organize on municipal time. “I began my work as a labor organizer in real earnest,” Roney recalled, “unencumbered with strenuous labor, possessed of a steady job and assured of $80 each month without deductions for loss of time.”4At the turn of the century, the waxing of union strength in the construction and transportation industries brought forth new men of power who built permanent, well-financed organizations and enjoyed life-long tenure. Michael Casey led the San Francisco Teamsters until his death in 1935, and Andrew Furuseth reigned over the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific until 1936 when a CIO revolt forced him to retire. Other leaders advanced from the local bureaucracy to higher posts: SFLC Secretary Andrew Gallagher parlayed his popularity into a seat on the Board of Supervisors, while Paul Scharrenberg, who began as a Furuseth protege, organized the California Federation of Labor and was, for many years, its chief officer and lobbyist.5 - eBook - ePub

A Short History of the U.S. Working Class

From Colonial Times to the Twenty-First Century

- Paul Le Blanc(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Haymarket Books(Publisher)

chapter 6 “Gilded Age”“Get rich; dishonestly if we can; honestly if we must,” the great novelist and humorist Mark Twain mockingly wrote of the spirit that triumphed throughout the country, a spirit of “money-fever, sordid ideals, vulgar ambitions, and the sleep that does not refresh.” Twain called the post–Civil War period the “Gilded Age” because the glitter of the era covered over widespread corruption. In fact, some historians refer to government generosity to corporations as the period of the “great barbecue,” after the nineteenth-century tradition whereby politicians bribed ordinary voters with a big dinner just before election day. For instance, railroads stretching westward were granted miles of land on either side of new lines. Railroads then sold the land to settlers, and charged them ruinous rates to ship or receive goods. The U.S. government sent troops into the West to clear away the native American peoples (the various Indian tribes) who were obstacles to the economic “progress” represented by the expanding corporate-capitalist economy. Back East, however, it turned its eyes as great fortunes were made selling “watered” stock or manipulating the stock market. In 1873, a severe national depression was triggered when financier Jay Cooke went bankrupt due to overextended railroad investments (although in later years he rebuilt his fortune by shifting from banking to mining). The economic liberty of a few was allowed to create misery for millions. The U.S. Constitution defended citizens’ rights only against governmental abuse, and not against abuse by corporations. In fact, the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, ostensibly written to protect citizenship rights of ex-slaves, was also purposely worded to expand the rights of corporations! Securing democratic control over the industrial economy would not be an easy task.National Labor UnionWhile corporations had a national form, trade-union organizations developed much more slowly. In 1866, workers formed the National Labor Union which focused much of its energies on limiting the work day to eight hours. Boston mechanic Ira Steward played a special role in agitating and educating for reduction of the workday in subsequent years, organizing and winning adherents to the Eight Hour Leagues. Instead of twelve to fourteen hours a day of work, there would be “eight hours for work, eight hours for rest, and eight hours for what we will.” It was iron molder William Sylvis, however, who was the moving force behind the NLU. - Angela B. Cornell, Mark Barenberg(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

To counter such industrial anarchy, trade unions and employer associations in the first third of the twentieth century episodically cooperated to standardize wages, working conditions, and market shares, especially in urban centers like Chicago, Detroit, and New York City. The giant steel mills and auto plants of the era captured the attention of the public – and a later generation of historians – but an equally consequential construction of a modern economy was underway among the jumble of far less imposing enterprises: at the building sites, trucking barns, breweries, eateries, and retail outlets where trade, governance, and unionism intersected (Cohen 2004: 273–276; Gordon 1994: 35–86). Some unionists like Sidney Hillman of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and Jett Lauck of the United Mine Workers had hoped that a species of what Colin Gordon calls “regulatory unionism” might bring economic order to those industries that failed to wield the pricing power or labor market controls deployed by the giant enterprises characteristic of the oligopolistic mass producers (Gordon 1994: 87–88). That project had clearly failed by the early Depression years. The unions and the local business associations with which they sometimes bargained were either too weak, too unpopular, or too constrained by Lochner-era legal edicts to make sectoral bargaining work on the municipal or regional level. For example, a pre-New Deal effort to set uniform wages and prices in the Chicago hand-laundry trade – there were more than 500 such establishments in Cook County – was challenged by an Illinois district attorney on the grounds that such an agreement constituted a form of “racketeering” not unlike Al Capone’s equally expansive effort to corner the wholesale liquor business so as to bring a certain regulatory order to a set of economic endeavors that then stood outside the law (Cohen 2004: 59–97). 90 Nelson Lichtenstein- eBook - PDF

From Conflict to Coalition

Profit-Sharing Institutions and the Political Economy of Trade

- Adam Dean(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

These labor unions also shared the experience of organizing workers in America’s two largest industries; in , roughly percent of all men, women, and children employed in American manufacturing were employed in either the cotton textile or iron and steel industries. 7 These “quintessential” industries were at the economic and political core of American industrialization. 8 The only other three sectors that rivaled cotton textiles and iron and steel, in terms of employment, were those that produced lumber products, men’s clothing, and machine tools. Since the lumber and clothing workers were not unionized during this period, it is not possible to systematically study their trade policy preferences. The machinists, who were organized by the International Association of Machinists starting in , did not develop prot-sharing institutions during our period of study, and did not support high tariffs. 9 Their lack of support for high tariffs can be gleaned from their ofcial periodical, The Monthly Journal of the International Association of Machinists. For instance, in it was reported that, “the 2 Taussig , . 3 Rogowski ; Midford ; Hiscox ; Scheve and Slaughter ; Manseld and Mutz . 4 Frieden . 5 Sanders ; Bensel . 6 Hattam ; Manseld and Mutz ; Ehrlich ; Ahlquist et al. . 7 United States , –. 8 Bensel , ; Silver , . 9 United States , –. The Gilded Wage protective system protected one class, but there was nothing to protect the workingman.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.