Languages & Linguistics

Alliteration

Alliteration is a literary device that involves the repetition of initial consonant sounds in a series of words within close proximity. It is often used in poetry, prose, and advertising to create rhythm, emphasis, and memorable phrases. Alliteration can add musicality to language and enhance the aesthetic appeal of written or spoken communication.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

12 Key excerpts on "Alliteration"

- eBook - PDF

- Nina Nørgaard, Beatrix Busse, Rocío Montoro(Authors)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Continuum(Publisher)

Key Terms in Stylistics Alliteration Alliteration is a stylistic device consisting of the repetition of the same consonant sound in nearby words. To qualify as Alliteration, in the strict sense of the word, the consonant sounds must occur in word-initial position. Alliteration has a cohesive effect, since identical sounds tend to tie words together if they occur in close vicinity. It can be employed for emphasis and mnemonic effects and is frequently used as a means of foregrounding in poetry, advertising, newspaper headlines, political slogans, etc. Examples of Alliteration thus occur in the first line of Keats’s poem ‘To Autumn’ ([1820] 1983): ‘Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness!’, as well as in the title of Gurinder Chada’s film Bend it Like Beckham (2002). Alliteration is sometimes used in a broader sense to refer also to what is otherwise known respectively as assonance and consonance. Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds in nearby words, usually in stressed syllables. Consonance, on the other hand, is used by some to refer to the repetition of consonant sounds in nearby words irrespective of their position, while others employ the term to refer to the repetition of final consonant sounds only. See also assonance, cohesion, consonance, foregrounding (Key Terms). Arbitrariness, Arbitrary It is a feature of human verbal language that – as a rule – the linguistic sign is arbitrary in the sense that no natural relation exists between the linguistic sig-nifier and that which is signified (Saussure, 1916). There is thus no ‘tableness’ about the word ‘table’ and nothing ‘bookish’ about the word ‘book’. Instead, the meaning of the linguistic sign is determined by convention, which means that a speech community has agreed on labelling a concept in a particular way, while another speech community calls it something else (English: ‘table’; - eBook - PDF

- Jonathan Roper(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

234 Alliteration in Culture and claims that they are fundamentally very similar phenomena (both involve repetition of syllables, copying prosodically prominent syl- lables) but with one important difference: Alliteration requires greater proximity than rhyme. Whereas rhyme occurs at the end of each line, Alliteration can take place between consecutive words within the same line. The repeated sounds’ closeness to one another creates a unifying aural effect throughout the passage. Alliteration in this sense is linked with the concepts of ‘structural echoes’ or ‘chiming effect’. Tamplin (1993) values highly the function of what he calls ‘structural echoes’, the same quality of sounds spreading over a poem, in unifying various aspects of the poem, especially in creating a metaphorical relationship between sound and form. A chiming effect is defined as ‘a phonetic bond between words’ (Leech 1969), and, like the notion of structural ech- oes, it is often metaphorically associated with the theme of the poem. Alliteration can be understood as a special case of chiming effect, where the echoing sounds are restricted to the initial consonants of words or syllables. This metaphorical function of Alliteration is especially indispensable for poetic language, and it can be found in sign language poetry as well. I will discuss the symbolic nature of Alliteration in a later section of this chapter. Sign language poetry Sign language poetry can be defined as a piece of poetic signing origi- nally composed and performed in a sign language by a Deaf person. It is different from ‘Deaf poetry’ which refers to any poetic activity that involves Deaf people, including poems composed by Deaf people in written language. It is also distinguished from the translation from spoken/written poetry. In short, sign language poetry is original work of Deaf people in their own language. Poetry is the height of linguistic activities in any language. - eBook - PDF

Classical Hebrew Poetry

A Guide to its Techniques

- Wilfred G. E. Watson(Author)

- 1984(Publication Date)

- Sheffield Academic Press(Publisher)

Also Kinnier Wilson, Iraq 18 (1956) 146; ZA 54 (1961) 74-77; Alonso Schokel, Estudios, 90. Also, O'Connor, Structure, 143. 9.3 Alliteration Notes on theory Alliteration is the effect produced when the same consonant recurs within a unit of verse. It is, in fact, a form of repetition, the repeated element being a consonant (see REPETITION). The following features of Alliteration need to be borne in mind: —Alliteration refers to consonants, not vowels; the same kind of repetition of vowel-sounds is termed assonance (see ASSONANCE). Of course the two kinds of sound repetition are related, and indeed often occur in combination. For clarity of presentation, though, they are here considered separately. 8 —Alliteration is here understood in its wider sense of consonant repetition and is not confined to word-initial Alliteration. —Near-Alliteration has also to be taken into account. By this is meant that similar-sounding consonants are considered to be equivalent. For example, /t, d and t/ can be grouped together, as can the sets /g,k,q/, /s,z,s/ and so on. The degree of Alliteration involved, though, is lesser than that of identical consonants. 9 8. The terms 'consonant Alliteration' and 'vowel Alliteration' are used by some scholars, e.g. Chatman in Sebeok, Style, 152. 9. For Hebrew a list is given by I. Casanowicz, Paronomasia in the Old Testament (Boston, 1894), 28-29; these interchanging consonants are: n/o, v&, D/T, v/v, o/n, n/p, p/a, «i/a,»/«. Margalit prefers the term 'partial Alliteration' e.g. Ps 119,13. 226 Classical Hebrew Poetry —Alliterative clusters are of particular importance. Sets can be strictly repetitive (mb—mb; sk—sk etc.) or quasi-repetitive (gz—qs; pt—bd etc.) or even with jumbled consonant sequences (nsk—skn). Such clusters may occur within the same colon or extend over several lines. In common with other poetic traditions where oral improvisation or recitation was the norm, Alliteration was comparatively significant in ancient Semitic verse-forms. - eBook - PDF

Doubling and Duplicating in the Book of Genesis

Literary and Stylistic Approaches to the Text

- Elizabeth R. Hayes, Karolien Vermeulen(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Eisenbrauns(Publisher)

The brilliance of Lincoln’s address, I submit, is not only its stirring content but the manner of elocution, which captures the audience from the start. 3. OED, s.v. “Alliteration.” 4. “Alliteration,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alliteration. 5. All five manuscripts of the Gettysburg Address commence with this same line, with only punctuation differences between and among them. For convenient access to the documents, go to “Gettysburg Address,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gettysburg_Address. 81 Alliteration in the Book of Genesis And so it is (or was) with the ancient Israelite consumers of (what would be- come) biblical literature, with its sounds and resonances echoing in the ears of the listeners. But back to our definition of Alliteration. As indicated above, most consider Alliteration to refer to the repetition of sounds at the beginning of a series of words. As we shall see below, however, the Hebrew writers enjoyed greater freedom and flexibility in creating the acoustic effect. First, given the root structure of Hebrew (and Semitic generally), the re- peated sounds are not found at the beginning of words necessarily but, rather, (a) may appear anywhere in a given word or words, 6 and (b) may be accompanied by other like-sounding consonants. Second, the Alliteration was heard not neces- sarily within consecutive words, but, rather, in words also further apart—some- times in proximity, sometimes at a greater distance. As such, given all the possible permutations and combinations, Alliteration in ancient Hebrew texts occurs with two or three identical consonants, two or three similar consonants, or any com- bination thereof; with the evocative sounds presented either in the same order or in scrambled fashion; with the sound effect placed either in the same verse or in adjacent verses; with the options either of highlighting just two crucial words in the text or of creating a veritable cluster of alliterative words; and so on. - Mick Short(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Remember that the use of phonetic symbols is not entirely consistent from one phonetics textbook to the next. Sound, meaning and effect 107 4. 2 Alliteration, assonance, rhyme and related matters The terms in the title of this section should be familiar, but it will help us to go over their definitions in some detail. To do so, we will use the examples listed below. It should be borne in mind that these phonetic schemes are themselves examples of phonetic parallelism, and therefore are often interpretable via the 'parallelism rule' described in 2.3. In the examples below, the phonetic schemes which are discussed are emboldened. 4.2.1 Alliteration Alliteration primarily involves the repetition of the same or similar consonants: Example 1 A dreadful winter passed, each day severe Misty when mild, but cold when clear. (George Crabbe, 'Tale 17: Resentment', lines 351-2) Here, the /m/ Alliteration in the first half of the second line binds together the concepts of mistiness and mildness and brings out the contrast with the second half of the line, which in turn exhibits Alliteration, binding together the words cold and clear. The next example shows that Alliteration primarily involves sounds and not spelling: Example 2 These fruitful fields, these numerous flocks I see, Are others' gain, but killing cares to me: (George Crabbe, 'The Village', I, 216-17) Killing and cares alliterate, and bind the meanings of the words together in spite of the fact that their initial sounds are represented by different letters. If alliterating sounds are also spelled the same this will help to make the Alliteration more obvious, but Alliteration can occur even when there is no 'spelling Alliteration'. In general, sounds seem to be more salient than spellings. Critics do sometimes point out eye rhyme (e.g.- eBook - ePub

Old English Runes

Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Approaches and Methodologies with a Concise and Selected Guide to Terminologies

- Gaby Waxenberger, Kerstin Kazzazi, John Hines, Gaby Waxenberger, Kerstin Kazzazi, John Hines(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

A Concise and Selected Guide to Terminologies

Prof. Dr. Gaby WaxenbergerGöttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities and LMU Munich English Department Schellingstr. 3 RG 80799 München GermanyDr. Kerstin KazzaziCatholic University of Eichstätt-Ingolstadt Academy Project RuneS Ostenstraße 28a 85072 Eichstätt GermanyProf. John HinesLavernock Road 45 CF64 3NX Penarth United KingdomThe first step to interdisciplinarity is to understand each other’s terminologies. This Guide is intended to be such a first step, proceeding from the terms occurring in this volume.1 Linguistic Terms

Gaby WaxenbergerKerstin KazzaziAlliteration

Alliteration is the relationship between words which begin with the same sound. In the early → Germanic languages (and indeed more widely) it is a frequently used discourse-stylistic feature for forming and unifying poetic (‘metrical’) units. Alliteration between consonants tends to be strictly phonemic (→ phoneme) while it is often found that any vowel is treated as alliterating with any other vowel irrespective of their actual → phonetic quality. This has been attributed to the glottal stop.In other words, Alliteration is used as a poetic device, defining the rhythm of a verse-line. Thus, it has a structuring function. In an Old English alliterating verse, the stressed syllables usually have the same initial consonant; all vowels and the consonant clusters sc-, st-, and sp- alliterate with each other.An example of an Old English alliterative verse-line is Beowulf l. 18:B ēowulf wæs b rēme, / b lǣd wide sprang.An example of a line with alliterating vowels is Beowulf l. 3:hū þā æ þelingas / e llen fremedon.Allograph

Allographs (e.g., ‹a›, ‹ɑ›, ‹A›) are sub-variants of a → grapheme - eBook - PDF

What is Poetry?

Language and Memory in the Poems of the World

- Nigel Fabb(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Orchard (2003) says that the English bishop Aldhelm composed much alliterative poetry in Latin, possibly under the influence of Old English. Rajam (1992) provides an exten- sive discussion of how Alliteration is used and classified in Tamil. Roper Traditions with rhyme or Alliteration 135 (2012) discusses Old English and Estonian Alliteration; he discusses how a particular meaning, such as ‘man’, becomes associated with a set of synonym- ous words, each of which begins with a different consonant, in order to be able to deploy the meaning in a line with any Alliteration. He notes that in some cases, the meaning is ‘stretched’ from its everyday meaning, so that, for example, Old English tolk meaning ‘translator ’ comes to be a t-initial synonym for ‘man’. This is a type of difficulty of meaning produced by formal requirements. Unsystematic Alliteration is reported widely. The Greek poets Aeschylus and Lucretius used Alliteration and to a lesser extent so did Pindar, though none systematically (Race 1997). Matejka (1962: 336) notes the use of alliter- ation in Old Church Slavonic and also describes the use of Alliteration in Latin. Peck (1884: 59) describes Alliteration in the Classical Latin of Lucretius and Virgil, particularly in the last two feet of the hexameter, which forms a kind of cadence using Alliteration as a way of restricting word choice at the end of the line. In Fabb (1999), I argue that Alliteration is more limited in its operations than rhyme, and specifically that the patterns of Alliteration can only connect adjacent poetic sections. For example, Alliteration holds between adjacent hemistichs in Old English within the long line and holds between adjacent hemistichs in Somali gabay over the whole poem. Alliteration holds between adjacent lines in an Icelandic couplet and in Mongolian stanzas and other sequences (Fabb 1997: 118, 160). With unsystematic exceptions, there are no ABAB patterns in Alliteration, though this is a pattern common in rhyme. - eBook - PDF

Contemporary Stylistics

Language, Cognition, Interpretation

- Alison Gibbons, Sara Whiteley(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

Keywords and summary Alliteration, assonance, consonance, homophones, iconicity, meter (foot, iambic, trocaic, spondaic, anapaestic, dactylic), offbeat, onomatopoeia (lexical, non-lexical), phonaestheme, phonaethesia, phonaesthetic fallacy, phoneme, phonetics, phonology, rhyme (end, internal, reverse, half), rhythm, syllable (onset, nucleus, coda, rime), word boundary misperception. Throughout this chapter, we’ve explored the ways in which writers can manipulate the phonological properties of language for literary effects. From using onomatopoeia, Alliteration and assonance, and dominant sound clusters, to rhymes and metrical patterning, writers can enrich the stories they tell by using techniques of sound patterning to create iconicity. The key thing for any stylistician is not to interpret such sounds or devices as indicative of any one thing. The literary interpre-tations you draw from sound patterning must be attentive to narrative context. 40 LITERATURE AS LANGUAGE Activities 1. Choose a poem, and perform a homophonic translation. So, try to substitute each word in the original text with a homophone or at least a similar sounding word. How does this make you think of the relationship between words differently? 2. Look at either (a) two literary examples in which the same or similar sound clusters are being used (e.g. sibilance) or (b) two texts that focus on the same subject. For the latter, for example, you could compare Matthew Arnold’s poem ‘Dover Beach’ with Sylvia Plath’s poem ‘Berck-Plage’, both of which describe the sea. Perform a pho-nological stylistic analysis of your two poems and compare them. How does your comparative analysis show up the validity of the phonaesthetic fallacy? For (a) how are the same sounds used in the creation of different meanings?; for (b) how are different sounds used to evoke similar meanings or iconic representations? 3. Choose a poem on which to perform your own sound patterning analysis. - eBook - ePub

- Katie Wales(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

continuous Alliteration (x x x x) there are patterns of transverse Alliteration (x y x y), etc.The extent to which Alliteration in such poetry can also be EXPRESSIVE is a matter of dispute. It seems hard to deny associations in such lines as:The sn aw sn itered ful sn art, that sn ayped the wilde(Sir Gawain and the Green Knight)(i.e. ‘The snow came shivering down very bitterly, so that it nipped the wild animals’).Alliteration as a device of FORM has occasionally been exploited in later literature by poets such as Gerard Manly Hopkins and W.H. Auden. For Hopkins in particular it takes its significance from its co-occurrence with other phonological patterns such as ASSONANCE , e.g.:I caught this m orning m orning’s m inion, kingdom of daylight’s d auphin, d apple-d awn-d rawn Falcon, in his riding …(The Windhover)■ alveolarIn PHONETICS , a consonant articulated when the tip and blade of the tongue touch the ridge (alveolum) behind the upper teeth; which is one of the significant parts of the mouth for English consonants. Hence the PLOSIVES /t/ and /d/ are alveolar; also the FRICATIVES /s/ and /z/, and the nasal /n/ (pronounced with the nose passage open).■ ambiguity; ambivalenceAmbiguity is double (or multiple) meaning: an ambiguous expression has more than one interpretation. The concept has, however, special implications in different disciplines.(1) Linguists would see ambiguity as a linguistic universal, common to all languages, one of the inevitable consequences of the arbitrariness of language, i.e. the lack of one-to-one correspondence between SIGNS - eBook - ePub

Traditions and Continuities

Alliteration in Old and Modern Icelandic Verse

- Ragnar Ingi Adalsteinsson(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Iceland University Press(Publisher)

This rule had been in place since before 1400; a few poets came to ignore it during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and to employ instead the alliterative practices of an earlier age, in all likelihood after having read the treatise by Jón Ólafsson Svefneyingur. It is clear, however, that by far the greatest number of poets alliterated sl only with sl, sm with sm, and sn with sn. Some scholars state that sk, sp and st are special equivalence classes without mentioning the other three gnýstuðlar. Discussion on the position of props follows a somewhat similar trajectory. The first scholars to mention this aspect of Alliteration were Jón Ólafsson Svefneyingur (1786) and Rasmus K. Rask (1818). Both treatments were unclear, however, thus making it difficult to follow the arguments, even when actual misunderstanding is avoided. It was not until Schweitzer’s article (1887) that clear and concise rules on the position of alliterative sounds were set out. Since then the quality of the discussion has improved. Authors focus more carefully on their subject than before, and at least a few now cite Schweitzer’s work (see Sigurður Kristófer Pétursson (1996 (1924):351). ______________ 2 The term Alliteration derives from the Latin word littera, ‘a letter’, an alphabetical element. Alliteration is defined in Thomas Blount’s Glossographia (1656) as ‘a figure in Rhetorick, repeating and playing on the same letter’ (see Minkova 2003:78). It is worth pointing out that Snorri Sturluson’s discussion of Alliteration is more than 430 years older than Blount’s gloss, see Háttatal in Chapter 1.7.1. 3 Willson (2008: 315, note 2) suggests ‘cluster Alliteration’, stating that the Icelandic term literally means ‘roaring Alliteration’ - eBook - ePub

Surprised by Sound

Rhyme's Inner Workings

- Roi Tartakovsky(Author)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- LSU Press(Publisher)

1 Hearing and Listening to Rhyme If negotiating with linguistic constraints and literary conventions comes with the territory of writing poetry, rhyme occupies a great part of that territory. Certainly, in the case of English, it is difficult to overstate the association between rhyme and poetry, or the significance of rhyme to poetry. This association is attested to in rhetoric by rhyme’s synecdochic or metonymic substitution for poetry itself. Rhyme-as-poem is a prevalent trope throughout much English-language poetry and is nowhere more evident than in William Shakespeare’s ending of Sonnet 17: “You should live twice, in it and in my rhyme.” In practice, rhyme’s prevalence is attested to by the overwhelming number of rhymed poems written by generations of poets. Of course, rhyme is not the only sound device, nor the earliest in the history of English poetry. A perfect or full rhyme is, in fact, one of numerous poetic sound devices, including assonance, Alliteration, consonance, and many forms of partial rhymes. But it is the more encompassing member among most of these weaker or partial sound relations because full rhyme typically requires a correspondence of both the vowel and the following consonant sounds of the last stressed syllable of each word. 1 Assonance was never used systematically in English verse, partial rhyme is best appreciated as a subset of full rhyme, and Alliteration, while carrying its own historical connotations of Anglo-Saxon prosody, seems, at least in poetic consciousness, more distant and dimmed today than rhyme. 2 Rhyme, both historically and phonetically, is set up to stand out in the soundscape of the poem or of poetry. As prevalent as rhyme is (or was —a question I will get to momentarily), it is easy to forget that rhyme’s entry into English poetry was a gradual process and one that—in spite of scholarly interest—remains somewhat murky. Murkier yet is the larger question of the historical origin of rhyme itself - eBook - ePub

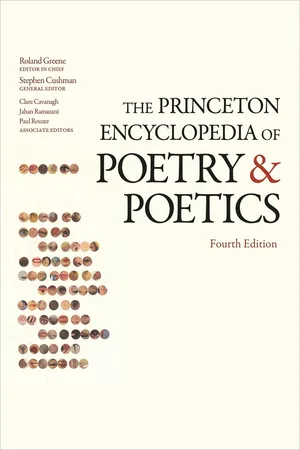

The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics

Fourth Edition

- Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, Jahan Ramazani, Paul Rouzer, Stephen Cushman, Clare Cavanagh, Jahan Ramazani, Paul Rouzer(Authors)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Princeton University Press(Publisher)

The Poetry Review 97 (2007).T. FURNISSCONSONANCE. In *prosody, consonance refers most strictly to the repetition of the sound of a final consonant or consonant cluster in stressed, unrhymed syllables near enough to be heard together, as in Robert Lowell’s “iron ic rain bow” and “Gobb ets of blubb er” or Robert Browning’s “Rebuck led the cheek -strap, chained slack er the bit,” where three final k sounds emphasize the stressed syllables buck -cheek -slack . Consonance parallels the repetitions in *Alliteration (initial consonant) and *assonance (vowel) and can be combined either within a syllable to produce other effects, such as *rhyme (assonance + consonance) or pararhyme (Alliteration + consonance). Critics have sometimes used the terms consonance, assonance , and Alliteration interchangeably with some loss of precision. Consonance also sometimes specifically denotes cases of pararhyme, an effect commonly found in early Celtic, Germanic, and Icelandic poetry, and in W. H. Auden’s “r ead er to r id er” or in early Ren. verse such as Luigi Pulci’s “Stille le stelle ch’a tetto era tutta.” This effect has been referred to alternately as bracket rhyme , bracket Alliteration , bracket consonance , or rich consonance , though it may be useful to distinguish this double echo from the single echo of final consonant repetition. This would allow one to say that “rider” both alliterates and consonates with “reader,” while in f ur -f air , f alliterates and r consonates. Consonance has often fallen loosely under the terms half rhyme , near rhyme , or slant rhyme , which may blur the distinction between differing vowel and consonant echoes. Combinations that appear to rhyme to the eye, such as lov e-mov e, may only consonate, though some such pairs are accepted by convention as rhyme. Several critics have identified other instances of “partial” or “semi” consonance when, e.g., one or more echoes involve slightly differing clusters, as in Dylan Thomas’s pairing plat es -hearts , which differs by the r in hearts but retains the t-s echo in both. Likewise, one may find “close” consonance between voiced and unvoiced final consonant echoes, as in the f and v of wife -lov e or s and z of hears e-war es . Consonance becomes more subtle, and harder to hear, between complex vowel or glide endings, as in the y of day -li e, also sometimes called semiconsonance

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.