Languages & Linguistics

Taboo

Taboo refers to a social or cultural prohibition against certain words, actions, or ideas. In linguistics, taboo language includes words or topics that are considered inappropriate, offensive, or forbidden within a particular culture or society. Taboo words often carry strong emotional or social significance and are typically avoided in polite conversation.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

9 Key excerpts on "Taboo"

- Mustapha Taibi(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Multilingual Matters(Publisher)

As Jakobson (1959) asserts, what can be expressed in one language may be expressed in another – at least to some extent. Effectively, social and cultural norms regulate the degree of explicitness, politeness, or circumspection that a given situation requires. Taboo topics and words are a case in point. According to Nida and Taber,The associations surrounding some words sometimes become so strong that we avoid using these words at all: this is what we call verbal Taboo. On the one hand, there are negative Taboos, with associated feelings of revulsion, or disgust, against such words as the famous four-letter words in English which refer to certain body organs and functions … On the other hand, there are positive Taboos, associated with feelings of fear or awe: certain words (often the names of powerful beings) are also regarded as powerful, and the misuse of such words may bring destruction upon the hapless user. (2003 [1969]: 91)Taboo is relative in two senses: cultural group (what is Taboo for some cultures may not be so for others) and intensity or offensiveness (the same topic or word may be Taboo for different cultures, but the face (cultural) threat, risk, or offensiveness associated with it may vary from one culture to another). Referring to swear words:Often the semantics of an item in this category are not the same across languages, which means that a word might be used in one language, but its supposed equivalent in the target language does not in fact mean exactly the same thing, or it cannot be used in exactly the same way or same context. (Stratiy, 2005: 242)For this reason, it is very important for translators and interpreters – especially community interpreters – to be aware not only of cultural differences related to Taboo, but also of the scale of face–threatening potential of the same act or expression for different cultural groups and different contexts.Regarding Arab cultures, it must be noted at the outset that, contrary to common belief, sex is not a Taboo semantic field. The topic of sexuality per se is neither positive nor negative from the perspective of discourse practices among equals. Rather, sex-related Taboos depend on a number of contextual factors such as when, where, and with whom the topic is to be discussed. Usually, sex may be discussed openly among peer groups of age and gender (e.g. teenage boys or adult women), but not between men and women (except in private settings or intimate interpersonal relationships) or between adults and children (except when the setting is educational and the language used is scientific or neutral). Space, time and interpersonal relationships influence the (culture-specific) judgments of acceptability and appropriateness.- eBook - ePub

The Challenge of Subtitling Offensive and Taboo Language into Spanish

A Theoretical and Practical Guide

- José Javier Ávila-Cabrera(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Multilingual Matters(Publisher)

Taboo as a concept is as old as humanity, and in order to better understand it, we need to go back in time. Primitive peoples associated Taboo terms with magical words and also superstition. The term ‘Taboo’ was borrowed by Captain James Cook in 1777, and ‘came to refer generally to human experiences, words, or deeds that are unmentionable because they are either ineffably sacred or unspeakably vile’ (Hughes, 2006: 151).In specific cultures, certain Taboo words are considered to be ‘off-limits’. Historically, Taboos have moved from religious to secular topics such as sex and race, ‘but they can manifest themselves in relation to a wide variety of things, creatures, human experiences, conditions, deeds, and words’ (Hughes, 2006: 462). According to Jay (2009: 153–154), these words ‘are sanctioned or restricted on both institutional and individual levels under the assumption that some harm will occur if a Taboo word is spoken’. Allan and Burridge (2006: 40) maintained that ‘the phrase Taboo language commonly refers to language that is a breach of etiquette because it contains so-called “dirty words”’. However, depending on the context, they can be softened through the use of euphemistic formulas, which will be discussed later in more depth.In order to have a more general idea of what Taboo entails, it is important to mention that every culture has its own way of dealing with Taboo words or concepts. For example, Native Americans, Japanese, Malayans and most Polynesians do not swear. According to Corral Esteban (2019), Native Americans do not swear or, at least, did not use any swear words in their ancestral languages. In this culture, language is a gift from their Creator and, therefore, something sacred. The fact that swearing does not occur in some cultures may be difficult for Western cultures to understand as slang and offensive language are used to express anger, surprise, shock, etc. Here, let us draw a distinction between Taboo language and slang. While the former can refer to language that may not be welcome, the latter refers to very colloquial words or phrases, which may or may not include swear words. Therefore, some slang words can be labelled as Taboo, but not all slang terms are necessarily unwelcome. - eBook - PDF

- Gerd Antos, Eija Ventola, Gerd Antos, Eija Ventola(Authors)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

2. State of the art in linguistic research on silence and Taboo Both silence and Taboo are important and frequent topics of discussion and analysis in recent linguistic research and are considered to be highly dependent on the culture and society in which they occur. This results in a variety of inter-pretations which can be attached to both phenomena. Summaries of research on silence and an overview of relevant publications can be found in Knapp (2000) and in Tannen and Saville-Troikje (1985). Ja-worski (1997) gives an interdisciplinary perspective on silence and discusses social and pragmatic perspectives of the power of silence (Jarowski 1998). The most recent monograph about Silence in Intercultural Communication has been written by Nakane (2007) and presents an analysis of silence in intercultural contexts by referring to examples from Japan and Australia. While linguistic research on silence has predominantly been published in English, research on Taboo, particularly studies on linguistic Taboo and euphem-ism, still seems to interest specifically German scholars. This is also reflected in the usage of terminology. The notion of Sprachtabu (‘linguistic tabu’) seems to belong especially to scientific literature written in the German language while equivalents in other languages (English: linguistic Taboo , French: tabou linguis-tique ; Italian: tabu linguistico ) have either been replaced by different formu-lations (French: interdiction linguistique ; Italian: interdizione linguistica ) or, in some instances, equivalents of Sprachtabu are used as a general term, but this phenomenon occurs less frequently than in the German language (cf. Schorch 2000: 6, fn 10). An analysis of Taboo discourse in languages other than German reveals that the usage of euphemisms is just as dominant when topics such as death or bodily functions are concerned. - eBook - PDF

- Keith Allan(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Elsevier Science(Publisher)

T Taboo Words K Burridge , Monash University, Victoria, Australia ß 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. The Nature of Taboo The English word Taboo derives from Tongan tabu . It entered the language towards the end of the 18th century. In this context, the word refers generally to forbidden behavior and includes such things as bans on naming dangerous animals, food restrictions, prohibitions on touching or talking to members of high social classes, and injunctions involving aspects of birth, death, and menstruation. Taboo items are avoided because they are thought to be ominous, evil, or somehow offensive to supernatural powers. To violate a Taboo automatically causes harm (even death) to the violator and perhaps his or her fellows. However, Taboos do not always involve the possibility of physical or metaphysical injury. Old Polynesia also has evidence of the sorts of Taboos on bad man-ners with which readers of this encyclopedia will be more familiar; in other words, social sanctions placed on behavior that is regarded as distasteful, or at least impolite, within a given social context (cf. Allan and Burridge, 2005: Chapter 1). The Taboos of contempo-rary Western society are of this nature. They rest ultimately on traditions of etiquette and are intimate-ly linked with social organization. A Taboo word in a language such as modern-day English is avoided, not because of any fear that harm may befall either the speaker or the audience, but because the speaker could lose face by offending the sensibilities of the audience. Some speakers would claim that to utter Taboo terms offends their own sensibilities, because of the supposed unpleasantness or ugliness of the Taboo terms themselves. In this context, euphemism is the polite thing to do, and dysphemism (or offensive language) is little more than the breaking of a social convention. Individual societies differ with respect to the degree of tolerance shown towards any sort of Taboo-defying behavior. - eBook - PDF

Swearing and Cursing

Contexts and Practices in a Critical Linguistic Perspective

- Nico Nassenstein, Anne Storch, Nico Nassenstein, Anne Storch(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Mouton(Publisher)

My reflection draws on the lessons learned from doing research with Taboo words. 2.1 Defining the category of Taboo words Once the subject matter has been properly defined, a research plan can be built. The first goal of research is to describe the phenomenon of interest. The term Taboo refers to a prohibited or restricted social custom; thus, Taboo words are those with restrictions on their usage. Here the term Taboo words is used collectively to refer to several semantic categories that comprise the corpus of words in many lan-guages that are restricted in usage. We should recognize Taboo words as a category of words that includes the following subcategories of offensive words and references: profanity/blasphemy, obscenity/indecency, slang, sex words (for https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501511202-002 body parts and behaviors), name calling, scatology, racist/gender/ethnic slurs, and vulgarity. Each of these subcategories contains different but over-lapping sets of words. Problems in the past have arisen when scholars were not clear in defining what they were studying, for example, using too broadly a spe-cific term such as profanity (religious word Taboos) or obscenity (legally defined sexual and excretory word Taboos). The goal for scholars is to be as clear and accurate as possible when defining what they are studying, the topic of their con-cerns. For a detailed discussion of definitional problems, see Adams (2016), Croom (2014), or Jay (1992, 2000, 2003, 2009, 2017). Taboo words can be single words but also phrases and conventionalized, in-sulting emotional expressions and idioms, for example, you think your shit don ’ t stink , you don ’ t know your ass from your elbow , or as translated literally from Farsi, what did you do, eat donkey brain ? We can see what kinds of word Taboos exist in a culture by looking at the use of non-Taboo euphemisms, which are ac-ceptable words used to replace Taboo words. - Otto F. Raum(Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

The past participle 'Tabooed' is used attributively, e.g. , in 'Tabooed king' = the king under prohibi-tions. The noun 'Taboo' generally means little more than 'prohibition', although the baneful in-fluence thought to be associated with the violation of such a prohibition is sometimes implied, e.g., in the sentence } Taboo flows out of the king' (Howells). The discussion of Taboo in Social Anthropology, Psycho-analysis and Psychiatry turns on the d i f f e r e n t i a t i n g q u a l i t y which distinguishes a Taboo from an ordinary prohibition. There is considerable divergence of opinion as to what constitutes this difference. Some authors maintain that the essential quality of the Taboo prohibition is i t s s t r i c t n e s s , its cate-gorical nature (Durkheim: 1939: 301). Few anthropologists accept this criterion, presumably because degree of severity is difficult to define without agreement on the measure. Some authors opine that Taboos are prohibitions with a peculiar kind of sanction. Marett (1933) describes this sanction as a ' c o n d i t i o n a l c u r s e ' and Westermarck (I, 60 and II, 63) limits Taboo to 'conditional curse used commonly only for the prevention of theft or the protection of property'. A third group of investigators finds the distinguishing quality of Taboo in t h e manner in - 7 -w h i c h t h e p u n i s h m e n t follows upon the breach of the prohibition. Webster and Seagle (p. 118) call it automatic, Westermarck (1,233) mechanical, Hobhouse (p. 420) direct, Redfield stresses immediacy. In this connection it is often pointed out that no judicial or execu-tive agency, whether human or divine, is assumed to be involved (Preuss: 80). Some experts push this view further and assert that we cannot talk of Taboo unless the sanction is character-ized as s u p e r -n a t u r a l , m y s t i c o r m a g i c o -r e l i g i o u s in nature (Notes and Queries, Wilson, M; Meyer Fortes 1945; Sumner, II, 1097; Hoebel).- eBook - PDF

- M. Ljung(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The contribution of swearing in such situations is the added strength supplied by the Taboo words necessary for swearing to take place. The word Taboo is Tongan in origin and was used in that social frame- work in rather complicated ways to refer to sacred places reserved for gods, kings, priests and chiefs. The word was borrowed into English by Captain James Cook in his 1777 book Voyage to the Pacific Ocean. Whatever the original meaning of the term (cf. e.g. Freud 1950: 18) it rapidly became used in English to denote something forbidden. For obvious reasons, however, absolute Taboos are unusual and according to Hughes (2006: 462–3) the term has now come to be used to denote ‘any social indiscretion that ought to be avoided’ and has acquired the modern meaning of ‘offensive’ or ‘grossly impolite’ rather than ‘strictly forbidden’. I claimed above that in order to qualify as swearing, an utterance must violate certain Taboos that are or have been regarded as in princi- ple inviolable in the cultures concerned. In most cases the Taboo viola- tion consists in the use of Taboo words, but there are exceptions to the rule. In certain common standardized insults involving in particular mothers and sisters there is often no actual mention of the Taboo words themselves and the insult is delivered in abbreviated form like Your mother! Your sister! (cf. account of world soccer final in Chapter 7). These insults are rare in English, but as Labov (1972) observes, they are used in certain varieties of American English. On the other hand, they are very common in the Romance and Slavic languages as well as in Arabic, Cantonese, Greek, Hindi, Mandarin, Turkish and others. However, as a result of increase in immigration, this type of swearing has made its way into societies and languages in which they were previously unknown. As shown in Ljung (2006), such expressions are now regarded as standard swearing in the Swedish spoken in immigrant areas in Stockholm. - eBook - ePub

Major Trends in Theoretical and Applied Linguistics 2

Selected Papers from the 20th ISTAL

- Nikolaos Lavidas, Thomaï Alexiou, Areti Maria Sougari, Nikolaos Lavidas, Thomaï Alexiou, Areti Maria Sougari(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter Open Poland(Publisher)

2.1. Taboo and Insulting Words

Modern Greek, like other languages, contains words, which people avoid using in most contexts, because they feel them extremely embarrassing or offensive. Words of this type vary from Taboo words to insults or swearing (cf. Crystal 1995 ; Mercury 1995 ; Allan & Burridge 2006 ). According to Crystal (1995 : 173), these three categories may overlap or coincide, but they are not identical: to call someone κώλος ‘an ass’ is to use a Taboo word as insult, but if used with enough emotional force could be considered an act of swearing. On the other hand, στουρνάρι ‘blockhead ’, is a term of insult, but it is neither a Taboo word nor a swear word. Finally, the swear word κατάρα ‘curse’ is neither a Taboo word nor an insult (cf. Ξυδόπουλος 2008).Taboo language contains the so-called ‘dirty words’, i.e. mainly terms for bodily organs associated with sex, excretion and the act of sexual intercourse (αρχίδι ‘prick’,μουνί ‘cunt’,κώλος ‘ass’), terms for activities involving these organs (καυλώνω ‘get horny’), terms for bodily effluvia issuing from these organs (κουράδα ‘turd’,σκατό ‘shit’), terms for disease, death and the supernatural (καρκίνος ‘cancer’,πεθαίνω ‘die’). The term ‘dirty words’ denotes people’s attitudes towards the denotations and connotations of these words, which are the most emotionally evocative of all language expressions (Allan & Burridge 2006 ). People not only avoid using them in polite society, but also tend to replace them by a more technical term (e.g. πέος ‘penis’,κόπρανα ‘stool’, πρωκτός ‘rectum’) or a euphemism, which refers to the Taboo topic in a vague or indirect way (e.g. έφυγε ‘be gone’ instead of πέθανε ‘died’, πουλάκι ‘cock’ instead of πούτσος ‘prick’) (Crystal 1995 ).According to Crystal (1995 : 173), swearing refers to the strongly emotive use of a Taboo word or phrase, and its function is to express a wide range of emotions, like annoyance, frustration or anger. Swearing can mark also social distance, as for example when swearing in public (το Xριστό! ‘God damn!’), or act as an in-group solidarity marker, as when a group shares identical swearing norms (Mercury 1995 ; Allan & Burridge 2006 ; Crystal 1995 ). According to the same author, swearing can be further divided into smaller categories like blasphemies, which show contempt towards God, profanities, which show contempt to holy things or people, and obscenities, which involve the expression of indecent sexuality (cf. also Mercury 1995 - eBook - PDF

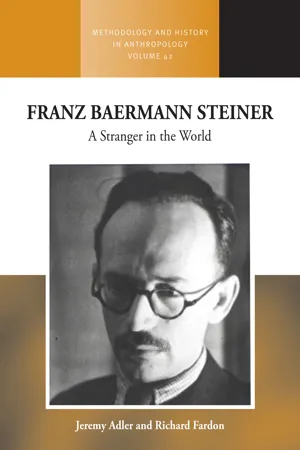

Franz Baermann Steiner

A Stranger in the World

- Jeremy Adler, Richard Fardon(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Berghahn Books(Publisher)

With Steiner, the strangeness of the repre-senting Western subject is never far from view. From the writings on Polynesia, as he relates, the word rapidly gained general currency in English in the sense of ‘sacred prohibition’ or the ‘forbidden’. The idea of ‘Taboo’ as a ‘problem’ emerged from this Western appropria-tion of an exotic term. Two following chapters attempt to recontextualize the specifically Polynesian senses of the term. Speculating from etymological ac-counts and usage, Steiner supposes that ‘Taboo’ most likely derived from ‘marked off’ and was used for things, circumstances and char-acteristics that were indivisibly ‘holy’ and ‘forbidden’, the two senses not being separable as they are in modern European languages. Put the other way, no European term was available to translate the un-divided sense of the Polynesian original. Referring to Malinowski’s ‘brilliant essay’ of 1923, Steiner notes that the meaning of the term can be found only situationally ‘in the manifold simultaneous over-lapping and divergent usages of the word’ (1999a: 119). The particularities of the Polynesian concept were related to Polynesia’s political organization and notions of power, mana . Power was measured by the recognized capacity to restrict, and chiefs of greater power could delegate some specific ability for interdiction to their inferiors. Mana and tabu classified and energized what was otherwise inchoate, indeterminate or of no significance, noa , and did so by imputing to the Polynesian world dangers that were of a piece with Polynesian political ideas and practices. The breach of Taboos was strongly sanctioned. Taboo, in its Polynesian context, thus exemplifies the broad thesis already presented in ‘On the Process of Civilization’.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.