Literature

American Gothic

"American Gothic" refers to a literary genre characterized by its portrayal of rural life, often featuring themes of isolation, fear, and the supernatural. It is closely associated with the works of authors such as Edgar Allan Poe and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and is known for its exploration of the darker aspects of American society and the human psyche.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "American Gothic"

- eBook - ePub

Republicanism and the American Gothic

American Gothic

- Marilyn Michaud(Author)

- 2009(Publication Date)

- University of Wales Press(Publisher)

5While it is no longer contentious to claim that American culture is ‘drenched in Gothic sensibility’, for many critics, its presence in the land of ‘light and affirmation’ remains an unremitting paradox.6 The popularity of American Gothic fiction indicates how ardently critics feel the need to explain the persistence of the form in a political and cultural environment seemingly divorced from traditional Gothic impulses. To account for a Gothic imagination in American culture, analysis has centred on psychology. Seen as a reflection of colonial anxieties, Puritan repression and pathological guilt resulting from the nation’s encounter with slavery and Indian massacre, the parameters of the American Gothic are marked primarily by ‘psychological, internalised, and predominately racial concerns’.7 In Love and Death in the American Novel, arguably the first work to focus exclusively on American Gothic writing, Leslie Fielder’s reading of early American texts exemplifies this approach: ‘European Gothic identified blackness with the super-ego and was therefore revolutionary in its implications; the American Gothic . . . identified evil with the id and was conservative at its deepest level of implications, whatever the intent of its authors.’8 Unlike their British counterparts, American writers are always in a state of ‘beginning, saying for the first time . . . what it is like to stand alone before nature, or in a city as appallingly lonely as any virgin forest’. For Fiedler, the Gothic is juvenile and repetitive because it deals primarily with a world of limited experience: a world American authors return to time and again due to their inability ‘to deal with adult heterosexual love and [their] consequent obsession with death, incest, and innocent homosexuality’. Contemporary writers, he claims, are doomed to repeat these patterns because they share a similar consciousness and the inescapable conditions of American life. Therefore, for Fiedler, the Gothic must be ‘symbolically understood, its machinery and décor translated into metaphors for a terror psychological, social and metaphysical’.9 - eBook - ePub

The Poetics and Politics of the American Gothic

Gender and Slavery in Nineteenth-Century American Literature

- Agnieszka Soltysik Monnet(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Gothic America (1997) saw the American Gothic as a map of the “cultural contradictions” haunting the “nation’s idealized myths” (10). In these and other examples, the term “American Gothic” is used to signify the fact that “America” and “Gothic” are no longer opposed terms but are, instead, intimately connected. According to this new configuration, the term “gothic” refers to violence, injustice, and horror and locates these in history rather than in the mind.In short, in the 1980s, “American Gothic” had become a hybrid term signifying a vision of American culture and history that was profoundly dystopian. A recurrent rhetorical feature of the American Gothic is to imagine the gothic as occupying a space “beneath” the surface of America, metaphorically speaking, because it is somehow hidden from casual view. For instance, Marianne Noble claims that “what the gothic achieves remarkably well is the act of unveiling … [and exposing] repudiated counter-narratives beneath genial fictions” (“The American Gothic” 170). The opening scene of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) enacts the paradigmatic gothic gesture of exposing the hidden beneath the visible: the camera pans over a clean and pretty small town and then descends underneath the neatly trimmed lawn to reveal the bugs crawling just out of sight in the dirt.While I do not want to deny the rhetorical value of figuring the gothic as hidden behind, beneath or deep inside America, I want to linger for a moment on the effect of putting these words side by side, as the expression “American Gothic” does. Originally opposed, now conceptually fused, these terms yoked together continue to produce a generative tension. This confrontation of opposing and ostensibly incommensurable concepts is an important dimension of the gothic as I define it. In other words, the signature gesture of the American Gothic is not just to expose the “gothic” hidden behind or inside the “American” but also to frame and focus on the contradictions between irreconcilable paradigms. - eBook - PDF

The Cambridge History of the Gothic: Volume 3, Gothic in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

Volume 3: Gothic in the Twentieth and Twenty-First Centuries

- Catherine Spooner, Dale Townshend(Authors)

- 2021(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

7 For many contemporary critics, it is the long, sad history of racial and economic injustice (in the South, and elsewhere) that forms the substrata of American culture and informs the contours of a specifically American Gothic writing. Increasingly, following Fiedler’s line of argumentation, cultural historians have articulated the centrality of American Gothic, even within an individualist, future-oriented, frontier-focused and democratic national mythos. For Teresa A. Goddu in Gothic America (1997), as for Kathleen Brogan in Cultural Haunting (1998), homage to the dead is central to the project of American renewal. Brogan accentuates the unresolved processes of mourn- ing the part of various racialised or minority or immigrant social communi- ties, communities who have been violently severed from their pasts or traditions via subjugation, genocide, enslavement or displacement. Goddu states categorically that the American South bears the burden of being somehow representative of a past that that cannot be shaken off: The American Gothic is most recognizable as a regional form. Identified with gothic doom and gloom, the American South serves as the nation’s ‘other,’ becoming the repository for everything from which the nation wishes to dissociate itself. The benighted South is able to support the irrational impulses of the gothic that the nation as a whole, born of Enlightenment ideals, cannot. 8 7 Patricia Yaeger, Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930–1990 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), p. 65. 8 Teresa A. Goddu, Gothic America: Narrative, History, and Nation (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), p. 3. Gothic and the American South, 1919‒1962 67 In The Palgrave Handbook of Southern Gothic, editors Susan Castillo Street and Charles L. - eBook - ePub

- Charles L. Crow(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Although Goddu's book ferrets out some of these dimensions more than others in American texts from Brockden Brown's to Toni Morrison's, her attention to cultural subordinations and how they haunt both their “masters” and victims matches the historical otherness of the Gothic as a mode throughout its history, based as it has been since Walpole on interplays between the “high” (tragedy or romance) and the “low” (comedy or the novel at his time), one reason for its being “low culture” for so much theory and criticism before 1960. The results just before and after Goddu have consequently come to include an astonishing array of cultural studies approaches to the American Gothic that continue to exfoliate and redefine its restless, and sometimes radical, nature and potentials. In addition to further studies of race (inside and outside the Southern American Gothic) inspired, as is Goddu, by Morrison's own non-fiction book of lectures, Playing in the Dark (1992), there have been provocative studies of how Gothic horror stories, especially in American films, show us the ways by which dominant culture produces, “queers,” and instigates resistance from many different instances of “deformity and imperfection” (Halberstam 1995: 155); eco-critical analyses of American Gothic texts that bring out the “ecophobia” projected onto “representations of nature” – such as the title figure in Poe's “The Raven” (1844) – “inflected with fear, horror, loathing, or disgust” as far back as Puritan New England (Hillard 2009: 688); and even accounts of how American Gothic tales of disease and disability, viewed through the recent lenses of disability studies, have revealed the cultural “horror [that can arise] in response to reform movements,” such as accommodations for the disabled, that seem a fearful “threat to a rational and enlightened republic” (Lisa Hermsen in Anolik 2010: 157) - Catherine Spooner, Dale Townshend, Angela Wright(Authors)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

2 . 17 The Gothic in Nineteenth-Century America charles l. crow The collision between Enlightenment and revolutionary Romantic values that produced the Gothic also produced the United States. Indeed, recent scholarship has asserted that that ‘the definitions of America and those of Gothic are so closely related as to be inseparable’, and that the ‘American Dream was from its inception a haunted, Gothic endeavour’. 1 American Gothic disrupts the dominant American narrative of technological and social progress, and reveals what is hidden or omitted by this narrative. It engages the large and inescapable facts of the emerging American nation: the twinned original sins of African enslavement and native American removal, the shifting frontier between settlement and wilderness, the rise of cities and of modern capitalism, poverty, disease and the changing roles of women. The repressed truth that American Gothic exposes is that Americans are not the people they believe themselves to be, either as individuals or as a society. Thus it could be argued, as I do, that the Gothic was even more essential to the American imagination in the nineteenth century than it was to that of Britain. The first great American novels were Gothic, and the centrality of the Gothic is obvious in the works of the Dark Romantics, Poe, Hawthorne and Melville. The importance of Gothicism continued, perhaps surprisingly, in the decades after the Civil War (1861–5), a period often described as the ‘Age of Realism’. The Gothic, from the beginning, drove technical innovation in American literature, and is responsible for some of its greatest works. 1 Joel Faflak and Jason Haslam, ‘Introduction’, in Joel Faflak and Jason Haslam (eds), American Gothic Culture: An Edinburgh Companion (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), pp. 1–22 (pp. 2–3). My approach also has been influenced by the work of Teresa A. Goddu, Eric Savoy and Leslie A. Fiedler. 376- eBook - PDF

- William Hughes(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

It is North American Gothic television that is arguably almost wholly responsible for the revival of an earlier serial Gothic tradition, as well as for the significant revisions made to the conven-tions of the vampire, werewolf and zombie in recent years. American Gothic is, inevitably, a significant influence upon both the stylistic THEORIES OF GOTHIC 173 and political tenor of global Gothic, as defined by Glennis Byron, this latter being the contemporary incarnation of the genre in which national atomisation is increasingly impinged upon by transnational homogenisation. Bibliography Aaron, Jane. Welsh Gothic . Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2013. Aldaner Reyes, Xavier. Spanish Gothic: National Identity, Collaboration and Cultural Adaptation . Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2017. Byron, Glennis, ed. Globalgothic . Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013. Crow, Charles. American Gothic . Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2009. Davison, Carol Margaret, and Monica Germanà, eds. Scottish Gothic: An Edinburgh Companion . Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017. Edwards, Justin D. Gothic Canada: Reading the Spectre of a National Litera-ture . Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2005. Edwards, Justin D. ‘British Gothic Nationhood, 1760–1830’, in Glennis Byron and Dale Townshend, eds, The Gothic World . London: Routledge, 2014, pp. 51–61. Gibson, Matthew. The Fantastic and European Gothic: History, Literature and the French Revolution . Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2013. Horner, Avril, ed. European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange, 1760–1960 . Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2002. Horner, Avril, and Sue Zlosnik, eds. Le Gothic: Influences and Appropria-tions in Europe and America . Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2008. Hughes, William, and Ruth Heholt, eds. Gothic Britain: Dark Places in the Provinces and Margins of the British Isles . Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2018. Kavka, Misha, Jennifer Lawn and Mary Paul, eds. - eBook - PDF

- Andrew Smith(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Edinburgh University Press(Publisher)

Lewis represents society as imploding because of its hypocrisies, whereas for Radcli ff e the truth will out in the end. It is important to note that these di ff erences are not just due to matters of moral vision, but are the consequence of the highly politicised ambience of the time which was shaped by radical debates about the existing social order. However, Britain did not experience a revolution, but America did, and it is important to consider how such changes a ff ected an American Gothic tradi-tion which like the British tradition has its roots in the eighteenth century. American Gothic So far the Gothic has been explored in a British context which has enabled us to see how national issues relating to class, wealth, and political power came to bear upon the form. However, the eighteenth the gothic heyday, 1760‒1820 33 century also saw the emergence of an American Gothic tradition which was subject to quite di ff erent pressures. The chief exponent of eighteenth-century American Gothic, and one of the first profes-sional writers in America, was Charles Brockden Brown, who wrote a series of novels that profoundly influenced the direction of the American Gothic, the most famous of which is Wieland ( 1798 ). The novel is written from the point of view of Clara Wieland, who recounts how her father came to America from Europe in order to spread his religious views. His somewhat severe Puritan beliefs prompted him to pray several times a day at a small temple which he had specially built in his garden. One night whilst praying he dies in a moment of spontaneous combustion (indicative of the pressures of his oddly solipsistic life). The novel then dwells on the activities of the adult Clara; her brother, Theodore; his wife, Catherine; and her brother, Pleyel. This quartet pursue a leisured life that revolves around religious and philosophical debate. - David Seed(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

From Woodrow Wilson to Bill Clinton, American presidents have articulated their vision of the national condition in similar binary terms. Employing a Gothic lexicon of corruption and degeneration, they have repeatedly punctuated the virtue of American progress with a deep suspicion of the perfectibility of man and of the progressive movement of history in time. The rhetorical structure of these presidential speeches is always the evocation of fear fol- lowed by the promise of renewal and return, to present a dialectics of good and evil, virtue and corruption, tradition and progress. Mid-century critics of the Gothic generally ignored the genre’s historical or politi- cal contours, focusing instead on symbolism and psychological interiority. Irving Malin’s New American Gothic (1962), for example, exemplifies this approach. Malin locates the distinction between contemporary Gothic writers and their nineteenth- century predecessors in their lack of interest in political tensions and their engagement with the “disorder of the buried life” (Malin: 5). Organized around the theme of narcissism, for Malin the typical Gothic hero is crippled by self-love. Contrasted with Modern Gothic 61 those heroes found in Hawthorne and Melville, who are “great” and “Faustian” in their narcissism, the characters of New American Gothic cannot demonstrate their self-love in strong ways: “The typical hero is a weakling. The only way he can escape from that anxiety which constantly plagues him is through compulsion. He ‘loves’ others because he loves himself: he compels them to mirror his desires” (Malin: 6). Yet, however valuable Freudian psychology has been in explaining the persistence of the genre in a nation seemingly divorced from traditional Gothic impulses, it is useful to remember that this interpretive framework arises out of a political culture that eschewed social and ideological conflict in favor of an all-pervading liberal consensus.- eBook - PDF

- Shirley Samuels(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

Key figures include Edgar Allan Poe, of course, but also Charles Brockden Brown, Hector St. John de Cre `vecœur, Henry Dana Sr., Washington Allston, John Neal, James Fenimore Cooper, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Harriet Beecher Stowe, George Lippard, Harriet Spofford, Alice Cary, Harriet Jacobs, Harriet Wilson, Emily Dickinson, and Louisa May Alcott. Nor is there room to explore the other pleasures and themes of early American Gothic, the largest gap being women’s gothic literature. Politics is not the only lens through which early American Gothic The American Gothic 177 can fruitfully be explored, though it is a particularly valuable one. In large part, that is because the action of repression is so frequently instigated by ideologies dissemin-ated by people with a vested interest. American Gothic explores those interests and their darker implications for the people influenced by them. Above all, it insists that the clash between cheerful ideology and a darker social reality is the central fact of American political life. It is for that reason that the gothic has always been a central fact of American literary history. R EFERENCES AND F URTHER R EADING Bergland, Renee L. (2000). The National Uncanny: Indian Ghosts and American Subjects . Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. Cre `vecœur, J. Hector St. John de (1994). Letters from an American Farmer (first publ. 1782). Ex-cerpted in The Heath Anthology of American Lit-erature , 2nd edn., vol. 1. Lexington, Mass.: Heath. Dayan, Joan (1999). ‘‘Poe, Persons, and Property.’’ American Literary History 11: 3 (Fall), 405–25. Edmundson, Mark (1997). Nightmare on Main Street: Angels, Sadomasochism, and the Culture of Gothic . Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. Edwards, Justin D. (2003). Gothic Passages: Racial Ambiguity and the American Gothic . Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. Fliegelman, Jay (1991). ‘‘Introduction.’’ In Wie-land and Memoirs of Carwin the Biloquist , vii– xliv. - eBook - PDF

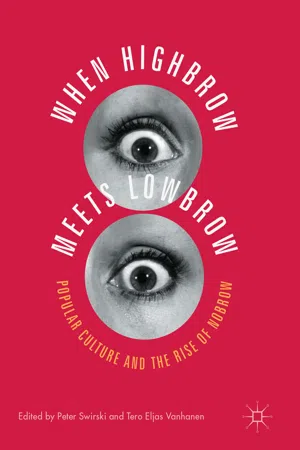

When Highbrow Meets Lowbrow

Popular Culture and the Rise of Nobrow

- Peter Swirski, Tero Eljas Vanhanen, Peter Swirski, Tero Eljas Vanhanen(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

The novel probes conven- tional morality, literary conventions and the publishing marketplace, reli- gious pieties, social customs, and epistemology. It asks how a well- meaning young American man like Pierre could reconcile his ethical obligations to an illegitimate sister with his seeming responsibilities to his family and his class. The situation the protagonist finds himself in amounts to an irresolvable moral aporia, pitting the realities of sexuality against antebellum ideals about the sanctity of family. Moral aporia are actually quite common in the Gothic genre, which is irresistibly attracted to situations and dilemmas that strain ordinary judgment and normative morality to its breaking point. This is why the Gothic has always been the genre of choice for writers wishing to explore transgressive topics. It can be considered the ideal generic tool for thinking outside the box. One of the ways in which Pierre is intriguingly both generic and experimental is in its insistence that real life is as improbable as the plots GOTHIC LITERATURE IN AMERICA 121 of the most lurid potboilers. In a much-quoted passage, the narrator argues that truth differs from literary conventions precisely in the way that it does not always make sense: By infallible presentiment he saw . . . that while the countless tribes of common novels laboriously spin veils of mystery, only to complacently clear them up at last; and while the countless tribe of common dramas do but repeat the same; yet the profounder emanations of the human mind, intended to illustrate all that can be humanly known of human life; these never unravel their own intricacies, and have no proper endings; but in imperfect, unanticipated, and disappointing sequels (as mutilated stumps), hurry to abrupt intermergings with the eternal tides of time and fate. 24 The part distinguishing “common dramas” from “higher emanations of the human mind” has often been read in terms of the high/low divide.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.