Literature

Didactic Poetry

Didactic poetry is a form of literature that aims to instruct or teach a moral or ethical lesson. It often presents a clear message or lesson to the reader, using storytelling, allegory, or direct advice. Examples of didactic poetry include works like "The Divine Comedy" by Dante Alighieri and "The Canterbury Tales" by Geoffrey Chaucer.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

7 Key excerpts on "Didactic Poetry"

- eBook - PDF

Persian Narrative Poetry in the Classical Era, 800-1500: Romantic and Didactic Genres

A History of Persian Literature, Vol III

- Mohsen Ashtiany(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- I.B. Tauris(Publisher)

Throughout the centuries, it has been used frequently for educational texts, providing a useful tool for learning the basics of prosody, grammar, religion and science in schools, but almost none of these texts can be regarded as “literature” in any sense.4 There is however a notable exception. The earliest example of an instructive poem is the Dânesh-nâme by Hakim Meysari, a medical compendium written in the 10th century in the form of a mathnavi with all that belongs to it according to poetic convention.5 In our discussion, only those didactic poems will be examined which were composed with a persuasive intention, i.e., those that preach certain moral and social values, which were presented in an attractive literary form enhancing their persuasive powers. Rhetorical embellishment, imagery, and narrative were their most effective tools. Narrowing down our subject further, the reader should be reminded that many of the most important works of Persian Didactic Poetry are of a mystical nature and belong to the great tradition of Sufi literature. As is the case with other poetic forms, notably the ghazal, the literary aspects of poems dealing with profane themes and those dealing with sacred themes are to a great extent identical, though in the longer poems that are exam- ined here the intentions of the poet are usually more clearly laid out than in the much shorter lyrical poems. Yet, even as far as their subject matter is concerned, a mixture of secular and religious elements is often found so that a watertight distinction cannot easily be made. In the present survey the mystical contents of the poems will not be our primary concern. Didactical poetry has been written in virtually any form available to the classical Persian poet. Also the qaside, the form par excellence for panegy- rics, has been used equally for the preaching of an ascetic way of life and a renunciation of the world designated as zohd, which term provided the generic appellation zohdiyyât. - eBook - ePub

- J.A.K. Thomson(Author)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

Chapter Four Didactic PoetryDOI: 10.4324/9781003462682-4T HE purpose of Didactic Poetry is, or was, to convey information; from which one is prone to draw the conclusion that it must be the invention of an educated age. The opposite is true; it is the uneducated, not the educated, who delight in the poetry of information. Consider how much of mediaeval literature consists in just that. Much that we now read for pleasure was first heard for profit or instruction. Even among so artistic a people as the Greeks we find that the Muses were the daughters of Memory. They were supposed to ‘know everything’—the expression is Homer’s—and when he invokes his Muse the appeal is not that he be inspired, but that he be informed. A primitive society, having no written records, must remember its traditions or lose its spiritual identity, and they are most easily remembered when they are put into verse. We cannot wonder that Didactic Poetry is very old. The earliest European representative of it is the Greek Hesiod, whose date is uncertain—perhaps the second half of the eighth century before Christ. The authenticity of the numerous works attributed to Hesiod has been much debated, and it seems best to treat him here as the founder of a kind or school of epic poetry rather than as the author of any particular poem or poems. The most certainly his is that in which we are most interested, the poem called Works and Days. The ‘works’ are tilling the ground, the ‘days’ are lucky and unlucky dates. In the midst of his practical instructions the poet offers a great deal of moralising advice suitable for people living in a small way upon the soil. In construction, where Homer is so great, Hesiod is totally incompetent. The Works and Days would be the merest jumble, if it were not in some measure held together by the sequence of the seasons, for each season has its own Works and Days. The style, which is that of the heroic epic, is not really suited to the theme, and for that reason it is often lumpish and unhandy, with none of the bright speed of Homer. In spite of all this the natural poetry of the earth shines through, and the Works and Days makes delightful reading. It is utterly honest and unsentimental, and no other poetry comes quite so near the heart of Mother Earth. There is not, perhaps there cannot be, any adequate translation of Hesiod. (Elton’s version is elegant, but to make Hesiod elegant is to misrepresent him.) For our purpose this hardly matters, for his direct influence upon English poetry has been almost negligible. It is an indirect influence that counts here, and that is Virgil. The Roman poet took Hesiod for his primary model in writing his Georgics, and the Georgics - eBook - PDF

- Victoria Moul(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

This remarkable and rewarding 1 On the role of Latin poetry in Renaissance education, see Chapter 3 in this volume, and Mack 2014. 2 Cowley 1661: 45–6. 3 On Cowley’s Latin see Bradner 1940: 118–22; Hinman 1960: 227–96; Ludwig 1989a; Hofmann 1994; Monreal 2005 and 2010; Moul 2011, 2012 and 2013. 180 work is ‘didactic’ in the fullest possible early modern sense: that is, in a much wider-ranging, more socially, politically and poetically central way than is usually meant by the sometimes deadening phrase ‘Latin Didactic Poetry’. Classicists use the term ‘Latin didactic’ to describe, principally, Lucretius’ De rerum natura (‘On the Nature of Things’) on Epicurean philosophy, the Georgics of Virgil (ostensibly on farming, including the care and cultiva- tion of crops, trees, livestock and bees), the Astronomica (‘Astronomical Matters’) of Manilius and, as an ironic take upon the form, Ovid’s Ars amatoria (‘The Art of Love’), Remedia amoris (‘Cures for Love’) and Med- icamina faciei femineae (‘The Facial Cosmetics of Women’). Horace’s Ars poetica (‘The Art of Poetry’) is sometimes included. 4 The use of ‘Didactic Poetry’ as a specific generic term is however contentious: there is very little acknowledgement in either ancient or early modern criticism of didactic as a genre of its own, rather than a form of epic, and a marked division in current classical scholarship between those who endorse and those who reject the broader term ‘didactic epic’. 5 Moreover, a considerable number of major texts usually excluded from consideration as ‘didactic’ have often been read and taught as storehouses of information or as moral or political guidance – examples range from Callimachus’ Aetia to Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Fasti, and even Virgil’s Aeneid, which became, like several of the poems discussed in this chapter, a school text within a few years of its publication. - eBook - PDF

Artificial I's

The Self as Artwork in Ovid, Kierkegaard, and Thomas Mann

- Eric Downing(Author)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

Again, we need to remember to distinguish between and to compare the poet's and the pupil's in-volvement with the conventions of the tradition; for again, the interplay between the different orders is very much at issue. The adoption of the didactic mode has several immediate consequences for the poem. For the poet, it at once provides a project, a plan, and in a curious fashion, a personality as well. The project, the poet's opus or labor, is encyclopedic and programmatic by nature. He identifies and circumscribes a field of activity or body of knowledge, collects and considers all relevant data and explores their every aspect, and organizes the whole into a coherent, versified schema. As A. S. Hollis says, the challenge is both poetic and scientific. It involves both tech-nical craft in molding the recalcitrant, often literarily preformed material into for-mal order, and extensive erudition and intellectual facility in encompassing the entire range of the engaged activity. 24 In its way, then, it automatically imposes an undertaking on the poet roughly, or functionally, equivalent to that which the 14 A. S. Hollis, in Ovid (Binns), p. 89^ !5 poet himself will impose on his audience of readers, who are likewise exhorted to systematize their activity and to attain mastery over their chosen realm in all its conceivable aspects. At the same time that the adoption of the didactic mode proposes to the poet a project, it also offers him a procedure: for the imitation of its literary conventions provides him with a practical, and sufficiently strict, code of conduct, a techni-cally simple method of invention which nonetheless serves as a supply complex method of expression. The poet has but to imitate an ideal and procedure fixed by tradition and literary convention; his activity and direction will be guided and conducted by the model of prior texts. At its simplest, he is given a language, a style filled with certain formulaic phrases and set rhetorical strategies. - Jason König, Greg Woolf(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

9 The Limits of Enquiry in Imperial Greek Didactic Poetry emily kneebone ∗ Didactic Authority Declarations of authority and expertise play a crucial role in proclaiming and reinforcing the instructive potential of didactic texts. In offering up a defined body of information on a specific topic, and in foregrounding the educative potential of their works, didactic authors necessarily claim for themselves a position of authority and place their own professed cre- dentials under scrutiny. As Catherine Atherton observes, ‘given its self- imposed task, at least the appearance of authority proves essential to the didactic enterprise, and even subversion of authority, or of expectations about authority ... presupposes (expectations of) access to authority, per- haps authority which is unique or uniquely appropriate’. 1 Didactic Poetry, however, is a form of literature that operates at the – to us, relatively unfamiliar – juncture between epic poetry and technical prose writing, and each of these traditions brings with it established, but by no means always compatible, conventions about authority and expertise. Authors of ancient prose manuals and technical handbooks, as this volume itself outlines, offer up a wide range of authoritative strategies by which they (affect to) guarantee the validity of the information they transmit. Ancient prose authors’ claims about their own proficiency often rest, for instance, on references to their personal experience, scholarly activity or professional credentials, to oral reports, eye-witness accounts or written sources (both poetic and prosaic) or on the citation of, or polemical engagement with, the views of laymen, rivals, experts and predecessors. Some of these are strategies also to be discerned in Greek didactic poems, yet ancient didactic poets frequently orientate their authoritative claims less towards their own technical expertise in the subjects they treat, and more towards their status, and expertise, as poets.- eBook - ePub

- George Ticknor(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

CHAPTER V.

Didactic Poetry. — Luis de Escobar. — Corelas. — Torre. — Didactic Prose. — Villalobos. — Oliva. — Sedeño. — Salazar. — Luis Mexia. — Pedro Mexia. — Navarra. — Urrea. — Palacios Rubios. — Vanegas. — Juan de Avila. — Antonio de Guevara. — Diálogo de las Lenguas. — Progress of the Castilian from the Time of John the Second to that of the Emperor Charles the Fifth.While an Italian spirit, or, at least, an observance of Italian forms, was beginning so decidedly to prevail in Spanish lyric and pastoral poetry, what was didactic, whether in prose or verse, took directions somewhat different.In Didactic Poetry, among other forms, the old one of question and answer, known from the age of Juan de Mena, and found in the Cancioneros as late as Badajoz, continued to enjoy much favor. Originally, such questions seem to have been riddles and witticisms; but in the sixteenth century they gradually assumed a graver character, and at last claimed to be directly and absolutely didactic, constituting a form in which two remarkable books of light and easy verse were produced. The first of these books is called “The Four Hundred Answers to as many Questions of the Illustrious Don Fadrique Enriquez, the Admiral of Castile, and other Persons.” It was printed three times in 1545, the year in which it first appeared, and had undoubtedly a great success in the class of society to which it was addressed, and whose manners and opinions it strikingly illustrates. It contains at least twenty thousand verses, and was followed, in 1552, by another similar volume, partly in prose, and promising a third, which, however, was never published. Except five hundred proverbs, as they are inappropriately called, at the end of the first volume, and fifty glosses at the end of the second, the whole consists of such ingenious questions as a distinguished old nobleman in the reign of Charles the Fifth and his friends might imagine it would amuse or instruct them to have solved. They are on subjects as various as possible,—religion, morals, history, medicine, magic,—in short, whatever could occur to idle and curious minds; but they were all sent to an acute, good-humored Minorite friar, Luis de Escobar, who, being bed-ridden with the gout and other grievous maladies, had nothing better to do than to answer them. - eBook - PDF

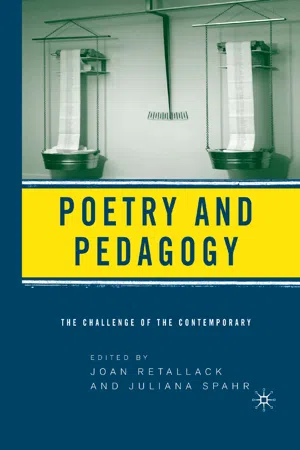

Poetry and Pedagogy

The Challenge of the Contemporary

- J. Retallack, J. Spahr, J. Retallack, J. Spahr(Authors)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Palgrave Macmillan(Publisher)

1fElbow could seem temporarily to kill off the teacher, he could not so quickly slay the institution. Samuel Johnson defines the didactic as "pre-ceptive; giving precepts: as a didactick poem is a poem that gives rules for some art."4 Summarizing one version of composition's structural transformation (of which Elbow was a part), Andrea Lunsford announces that in "basic writing dasses ... set lec- tures should always be avoided. 1nstead, the dasses should comprise small workshop groups in which all members are active participants, apprentice- writers who are 'exercising their competence' as they learn how to write

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.