Physics

Attractor

An attractor in physics refers to a set of physical properties or states towards which a system tends to evolve over time. It represents the stable equilibrium points or patterns that a system naturally gravitates towards, even in the presence of external disturbances. Attractors are fundamental to understanding the behavior of complex dynamical systems.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

5 Key excerpts on "Attractor"

- eBook - ePub

Managing Emergent Phenomena

Nonlinear Dynamics in Work Organizations

- Stephen J. Guastello(Author)

- 2001(Publication Date)

- Psychology Press(Publisher)

The presentations that follow emphasize qualitative analysis of phenomena. I tread lightly on the equations and original mathematical thinking. Fortunately, applied science uses the products of the mathematics; this is not necessary to revisit proofs and such. Several books serve as general references for the sections of Attractors, bifurcations, and chaos: R. H. Abraham and C. Shaw (1992) and F. D. Abraham, R. H. Abraham, and Shaw (1990), Kaplan and Glass (1995), Nicolis and Prigogine (1989), Puu (2000a), and Thompson and H. B. Stewart (1986).AttractorS AND STABILITY

An Attractor is a piece of space. It has a special property such that if an object gets too close to this space, the object is pulled into it and does not leave it, except under special conditions. The perimeter of the space of an Attractor is the Attractor’s basin. If the object does not fly close enough to the perimeter of the basin, the object keeps going on its merry way. The pathways of objects flying outside the perimeter, or within the basin of the Attractor are collectively known as the vectorfields.The notion of an Attractor overlaps in meaning with the more archaic term equilibrium, although the latter is less specific in terms of formal topological dynamics. According to Goldstein (1995), “equilibrium” originated in ancient Greek writing with the meaning of a balance of forces. That essential meaning carries through into 20th century economics. Economists, along with the rest of us, will recognize that not all equilibria are unchanging and stable. Some forms of balance, (such as some of the Nash equilibria in game theory in Chapter 5 ) are fragile. Hence, in common language we speak of “upsetting a delicate balance” or we instruct each other, “not to breathe on it or it will fall apart.” Thus, as Goldstein continues, stability and equilibrium are not synonymous, and any simple attempt to use the two terms with equivalent meaning could present confusion. Although it is sometimes useful to continue to think of equilibrium states, which imply a balance of some sort, alongside the concept of Attractor, it is also a good idea to keep the two concepts separated when making the distinction between a mathematical abstraction and a physical realization of the abstraction.Systems that are stable are unlikely to change in any appreciable way, if at all. An instability implies that a change will take place, that the results are not predictable, and that a particular result is not likely to occur again in repeated experiments. The classical topological definition, of Andronov and Pontryagin from the 1930s, is that “. . . - eBook - ePub

- Zoltán Dörnyei, Peter D. MacIntyre, Alastair Henry(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Multilingual Matters(Publisher)

There is one existing alternative: we can use the term ‘variable’ to refer to a condition of a self-organised pattern (Byrne, 2002, 2009). If we leave aside L2 learners and instead examine L2 achievement as the dynamic system, then personality and language aptitude can be conceptualised as conditions/variables that impact on any contextual outcome of the system dynamics. Determining whether to refer either to (1) a system component; or (2) a condition for self-organised patterns as ‘variables’, will depend on carefully operationalising the characteristics and boundaries of the dynamic system, and specifying the level and timescale (e.g. micro, meso, macro) on which we are observing it (de Bot, this volume). For clarity in dynamic systems motivational research, it is critically important to define the system being considered.Other Types of Attractor StatesPeriodic Attractor states are one step up in complexity because they provide more possibilities for variations in system behaviour than is the case for fixed-point Attractor states. A periodic Attractor state – also known as a limit-cycle Attractor state – represents two or more values that the system cycles back and forth between in a periodic loop. Patterns emerge when events or behaviours repeat themselves at regular intervals (Abraham & Shaw, 1992). Examples of periodic Attractor states can be seen when the students in our high school class begin a school year with a high level of enthusiasm and expectancy of success, but as the semester progresses the class loses its edge as the familiar routine turns to a monotonous grind and, towards the final weeks of the semester, the students contract the so-called ‘senioritis’ virus, are repeatedly absent and have a generally dismissive and apathetic attitude – a pattern that seems to repeat itself year in and year out. Within a particular language lesson we might also see these students starting a task using only the L2, then gradually getting carried away until they are all mainly using the L1 on-task, before eventually reverting back to the L2 once they are reminded to do so by the teacher.Strange Attractor states – also known as chaotic Attractor states – represent values that a system tends to approach over time but never quite reaches (Strogatz, 1994). The motion of a system in a strange Attractor state is called chaotic, because the dynamics trace a somewhat erratic or irregular pattern that never quite repeats itself, although these systems do in fact show complex forms of organisation that can be understood after the fact (Gleick, 2008). Weather patterns that we experience from day to day are an excellent example of this. The weather can be difficult to predict with precision, but we can always look back on the movement and interactions among weather systems to explain the weather that occurred (e.g. why a tornado formed, why a hurricane veered away from land or how ocean currents affect a summer day). In SLA, the L2 Self System (and the Ideal L2 Self in particular) might be considered a strange Attractor state. The competing motivational forces acting simultaneously on the learner will draw the learner’s attitudes and behaviours into a dynamic pattern that never exactly repeats itself. The Ideal L2 Self can be something of a moving target as progress is made toward goals and new, more challenging goals are constructed (see Henry, Chapter 9 - No longer available |Learn more

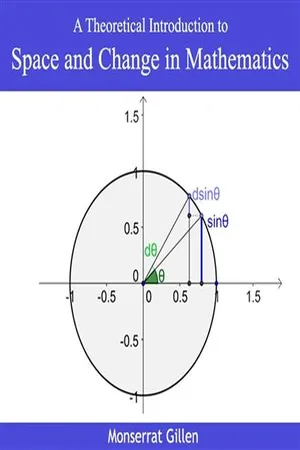

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ Chapter- 6 Dynamical System and Chaos Theory Dynamical system The Lorenz Attractor is an example of a non-linear dynamical system. Studying this system helped give rise to Chaos theory. A dynamical system is a concept in mathematics where a fixed rule describes the time dependence of a point in a geometrical space. Examples include the mathematical models that describe the swinging of a clock pendulum, the flow of water in a pipe, and the number of fish each spring in a lake. ________________________ WORLD TECHNOLOGIES ________________________ At any given time a dynamical system has a state given by a set of real numbers (a vector) which can be represented by a point in an appropriate state space (a geometrical manifold). Small changes in the state of the system correspond to small changes in the numbers. The evolution rule of the dynamical system is a fixed rule that describes what future states follow from the current state. The rule is deterministic; in other words, for a given time interval only one future state follows from the current state. Overview The concept of a dynamical system has its origins in Newtonian mechanics. There, as in other natural sciences and engineering disciplines, the evolution rule of dynamical systems is given implicitly by a relation that gives the state of the system only a short time into the future. (The relation is either a differential equation, difference equation or other time scale.) To determine the state for all future times requires iterating the relation many times—each advancing time a small step. The iteration procedure is referred to as solving the system or integrating the system . Once the system can be solved, given an initial point it is possible to determine all its future points, a collection known as a trajectory or orbit . - eBook - PDF

- Alvin M Saperstein(Author)

- 1999(Publication Date)

- World Scientific(Publisher)

It is the end point (or curve) which the system reaches as a limiting process and never again leaves. (During finite times the configuration gets closer and closer to the limiting value but may actually not ever equal the final Attractor value(s). Any point of 72 Dynamical Modeling of the Onset of War the configuration-space or phase-space graphs representing a system, is an allowed starting point of the system's evolution, since, by construction, the graphs represent all possible system configurations and the dynamical system laws are supposed to be able to take you from any allowed configuration of the world system to its immediately succeeding (by necessity) configuration. However, any point is not an allowed end point. End points, Attractors, are only those configurations for which the succeeding configuration is also an end point. The system laws, acting upon a system represented by a point in an Attractor, only can take the system to another Attractor configuration. For example, if the system was initially represented by point x . in Fig. 3a, it would remain in this configuration forever; if it started somewhere in the closed curve Attractor of Fig. 3b, it would endlessly cycle about that loop. Since all points may be starting points whereas not all points may be points on an Attractor, there are fewer - usually far fewer - of the latter than of the former. (That is, only comparatively few international configurations can be expected to remain stably fixed or cyclic.) Hence, in a given theory, many orbits, starting from many different initial values, may converge to the same Attractor (Fig. 4 a or b). The set of all points which, acting as initial values, evolve to the same Attractor, is said to be the basin of attraction for that Attractor. - Arturo Buscarino, Luigi Fortuna, Mattia Frasca(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

In this chapter strange Attractors and chaos in continuous-time systems [22, 70] are presented. As the reader can observe the route of the book is in agreement with the graph initially reported in Chapter 1 and referred to as Figure 1.3. Increasing the number of variables and including strongly non-linear terms, more complex phenomena are observed. This chapter discusses methods and numerical experiments on continuous-time systems with chaotic Attractors. 107 108 Nonlinear Circuit Dynamics with MATLAB and Experiments The electronic implementation and applications of chaotic elementary cir-cuits will be the focus of Chapter 8. 5.1 Features of chaos in continuous-time systems All the fingerprints of chaos in discrete-time systems are also retrieved in continuous-time systems. Therefore • aperiodic oscillations of the state variables, • high sensitivity to initial conditions, • sensitivity to parameter changes, • period doubling cascades, if any, ruled by the Feigenbaum constant, • long-term unpredictability, • signals with a wide spectrum, similar to that of white noise, are all features of continuous-time chaotic systems as well. Moreover, since in deterministic systems state space trajectories have no common points, aperiodicity in autonomous continuous-time systems is only possible if the number of state variables is at least three. In the case of continuous-time systems, Attractors may also be strange . The term refers to the fact that the orbit is bounded, but not periodic or convergent; on the contrary, it has a complex fractal structure. Chaotic systems display strange Attractors, that is, the trajectories are confined in a limit set, in which an infinite number of trajectories approach each other without intersecting one another. Given any point of a trajectory, at some time the trajectory will return arbitrarily close to that point, but will never pass again through the same point, thus forming a dense set of points in a specific geometric structure.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.