Bohr Model of the Atom

What Is the Bohr Model of the Atom?

The Bohr Model of the Atom, proposed by Niels Bohr in 1913, depicts the atom as a small, positively charged nucleus surrounded by electrons moving in fixed circular orbits (Neil D. Jespersen et al., 2021). Often likened to a miniature solar system, this model was the first to successfully account for the Rydberg equation and the spectral lines of hydrogen (Neil D. Jespersen et al., 2021). It represents a pivotal transition between classical physics and modern quantum mechanics, forming part of the "old" quantum theory (Mark Fox et al., 2018).

Core Principles and Conceptual Foundations

Bohr introduced the revolutionary idea that an electron's energy and angular momentum are quantized, meaning they can only exist in specific, discrete states (Mark Fox et al., 2018)(Morris Hein et al., 2021). Electrons occupy "stationary orbits" where they do not radiate energy, defying classical electromagnetic theory which suggested accelerating charges should lose energy and spiral into the nucleus (Mark Fox et al., 2018)(John D. Cutnell et al., 2021). These orbits are identified by a quantum number, n, with the lowest energy level (n=1) known as the ground state (Neil D. Jespersen et al., 2021).

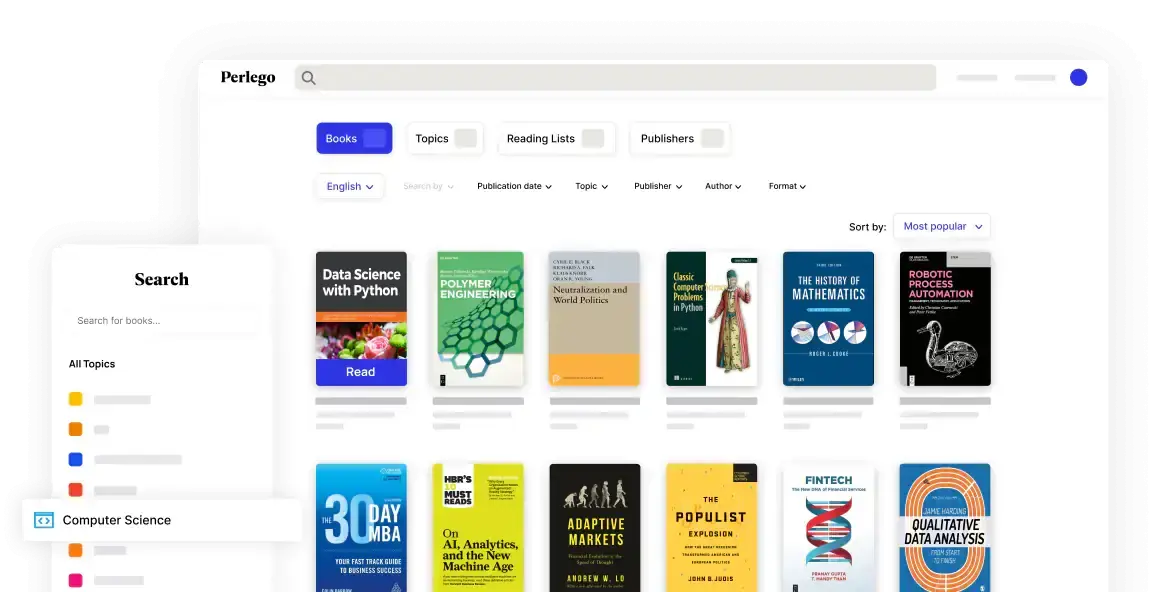

Your digital library for Bohr Model of the Atom and Physics

Access a world of academic knowledge with tools designed to simplify your study and research.- Unlimited reading from 1.4M+ books

- Browse through 900+ topics and subtopics

- Read anywhere with the Perlego app

Functional Application and Mechanisms

The model functions by balancing the Coulomb attraction between the positive nucleus and negative electron with the centripetal force of orbital motion (J. R. Eaton et al., 2013). Bohr postulated that angular momentum is restricted to integer multiples of Planck’s constant divided by 2π (Robert K Logan et al., 2010). When an electron drops from a high-energy excited state to a lower-energy orbit, it emits a photon with a frequency corresponding to the energy difference between those states, explaining the observed line spectrum of hydrogen (Morris Hein et al., 2021)(John D. Cutnell et al., 2021).

Limitations and Theoretical Evolution

Despite its successes, the Bohr model is incomplete as it cannot accurately predict the spectra of atoms with more than one electron, such as helium (George C. King et al., 2023)(Kenneth S. Krane et al., 2020). It also violates the Heisenberg uncertainty principle by assigning precise positions and velocities to electrons (Kenneth S. Krane et al., 2020)(James N. Spencer et al., 2011). Modern physics has since replaced Bohr's fixed orbits with quantum mechanical "orbitals," which describe regions of probability rather than definite paths (Mark Cracolice et al., 2020)(James N. Spencer et al., 2011).