Physics

Contact Forces

Contact forces are interactions between objects that are physically touching each other. These forces can include tension, friction, normal force, and applied force. They are called "contact" forces because they require direct contact between the objects involved, and they can affect the motion and behavior of the objects in various ways.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Contact Forces"

- eBook - PDF

Engineering Mechanics: Statics

Modeling and Analyzing Systems in Equilibrium

- Sheri D. Sheppard, Thalia Anagnos, Sarah L. Billington(Authors)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

As noted in Section 2.1, Contact Forces result from the electrical and magnetic interactions that are responsible for the bonding of atoms. Under this general heading are: • Normal contact force • Friction force Check One good check is to plug the calculated value of r into (1) and (2) and confirm that each equation yields the same value of gravitational force on Spirit. If you don’t get the same value, check to make sure you have used all the correct planetary data and repeat the calculations to confirm that all of the numbers were properly entered into a calculator. 2.3 Contact Forces 35 • Fluid contact force • Tension force • Shear force We will consider each of these in turn, in the subsections that follow. Normal Contact Force Whenever two solid objects are in contact with each other, each exerts on the other a force that is perpendicular to the two contact- ing surfaces and is called a normal contact force. For example, when a pianist hits a piano key, his fingertip exerts a normal contact force on the key and the key exerts an equal and opposite normal contact force on his fingertip (Figure 2.3.1). Similarly, a book lying on your desk exerts a normal contact force on your desk, and the desk exerts an equal and opposite normal contact force on the book. Normal con- tact forces are directed so as to bring the two solids together. What this means in practical terms is that a clean fingertip contacting the top surface of a piano key can push on the key but can’t pull it, as illustrated in Figure 2.3.2. Friction Force If you attempt to slide one solid object over another, the motion is resisted by interactions between the surfaces of the two objects. This resistance is a friction force and is oriented parallel to the two contacting surfaces in a direction opposite the direction of (pending) motion. - Janice VanCleave(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Jossey-Bass(Publisher)

Thus, the momentum of freefalling objects will be compared. Contact Forces are those forces applied directly to an object. Friction is the force between any two surfaces in contact with each other. Static friction occurs between two surfaces that are not in motion. If the two surfaces are in contact long enough there is an exchange of surface molecules. They become bonded together and very difficult to separate. This is why it takes more force to get some objects to start moving. Kinetic friction is the resistance to the motion of one surface moving across another surface. Drag is the contact force of fluids acting on objects moving through them, such as boats in water and aircraft in air. Buoyant force is an upward-directed contact force of fluids acting on objects immersed in them. This can be objects in water or balloons in air. One of the activities guides you in calculating a buoyant force. Torque causes rotation and is referred to as a turning force. Turning forces are Contact Forces that cause rotation about a center point. Examples are a wheel, a jar lid, or a seesaw. The magnitude of torque is the product of force applied times the distance the force is from the point of rotation. The point of rotation for a wheel or lid is its center; the point of rotation for a seesaw is the pivot, the point the board rotates around. Balance has to do with torque applied to either side of the center of gravity of an object or system. The center of gravity is the point where the weight of an object or system is considered to be concentrated so that if supported at this point, the body or system would be balanced. Stability is the resistance of an object to falling over. Again, the center of gravity is considered. It is actually all about balance and whether the torque acting on either side of the center of gravity is equal but in opposite directions.- eBook - PDF

Questioning the Universe

Concepts in Physics

- Ahren Sadoff(Author)

- 2008(Publication Date)

- Chapman and Hall/CRC(Publisher)

23 4 Forces 4.1 THE FUNDAMENTAL FORCES What is a force? One answer is that it is a push or a pull. A better answer, that we will find to be more useful, is that it is an interaction between two or more objects. For most of our discussion, two objects will suffice. Forces are no strangers to us since we interact with all sorts of things every day. Below is a list of forces I have compiled. Before reading my list, it would be instruc-tive for you to take out a piece of paper and make your own list. Hopefully you will come up with some not on my list. Gravity Electric Weak nuclear Strong nuclear Centrifugal Magnetic Centripetal Friction Wind force Contact force (between surfaces) Muscular force Chemical Atomic I am sure you have noticed that my list is arranged in columns or categories. Let us look at the last column first. Both items are, in fact, not forces at all, but adjec-tives describing the action of a particular force. A centrifugal force is any force that is directed outward from the center of a curve when an object is traveling in curved motion. Similarly, a centripetal force acts inward toward the center of the curve. Gravity is usually the force most people list first, as I have. It, of course, is very important to us since it keeps us bound to the earth and the earth to the sun. The second column contains many familiar forces under one heading. Why? Because all these seemingly different forces are all due to only one force. Electric and magnetic are not separate forces, but just different manifestations of what is known as the electromagnetic force (we will discuss this in more detail shortly). The force that holds the atom together is not some special new force, but is just due to the electri-cal attraction of the negatively charged electrons to the positively charged protons in the nucleus. Similarly, different atoms interact by the attraction or repulsion of the electrons and protons in one atom acting on the electrons and protons of another atom. - eBook - PDF

- Daniel Kleppner, Robert Kolenkow(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

FORCES AND EQUATIONS OF MOTION 3 3.1 Introduction 82 3.2 The Fundamental Forces of Physics 82 3.3 Gravity 83 3.3.1 The Gravitational Force of a Sphere 84 3.3.2 The Acceleration Due to Gravity 85 3.3.3 Weight 86 3.3.4 The Principle of Equivalence 87 3.3.5 The Electrostatic Force 88 3.4 Some Phenomenological Forces 89 3.4.1 Contact Forces 89 3.4.2 Tension—The Force of a String 89 3.4.3 The Normal Force 91 3.4.4 Friction 92 3.5 A Digression on Di ff erential Equations 95 3.6 Viscosity 98 3.7 Hooke’s Law and Simple Harmonic Motion 102 Note 3.1 The Gravitational Force of a Spherical Shell 107 Problems 110 82 FORCES AND EQUATIONS OF MOTION 3.1 Introduction The concept of force is central in Newtonian physics. This chapter de-scribes the gravitational force and the electrostatic force, two of the fun-damental forces of nature. We also discuss several phenomenological forces, for example friction. Such forces are commonly encountered in “everyday” physics and are approximately described by empirical equa-tions. Because the concept of force is meaningful only if one knows how to solve problems involving forces, this chapter includes many examples in which Newton’s laws are put into practice. The problem of calculating motion from known forces frequently oc-curs in physics. For instance, a physicist who sets out to design a particle accelerator employs the laws of mechanics and knowledge of electric and magnetic forces to calculate how the particles will move in the accelera-tor. Equally important, however, is the converse process of deducing the physical interaction from observations of the motion, which is how new laws are discovered. The classic example is Newton’s deduction of the inverse-square law of gravitation from Kepler’s laws of planetary mo-tion. - eBook - PDF

Granular Media

Between Fluid and Solid

- Bruno Andreotti, Yoël Forterre, Olivier Pouliquen(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

For larger forces, deviation from the Hertz law is observed. For example, in the fully plastic regime, one can assume that the contact pressure F N /(πa 2 ) reaches a constant value called the hardness H of the material. Using a ∼ √ 2δR gives the relationship F plastic N ∼ HR δ. (2.4) Although the pressure is constant, the contact force still increases with indenta- tion due to the increase in contact area, thus preventing the bodies penetrating further. 2.1.2 Solid friction In addition to the normal component, the contact force generally has a tangential component owing to the friction between surfaces in contact. The physics of solid friction is an old topic that is still the subject of active research (Persson, 2000; Baumberger & Caroli, 2006). For a granular medium, friction is a key concept that will be found throughout this book, from the grain to the packing level. 18 Interactions at the grain level F T 1 F T 2 F T 1 = F T 2 F N F T R T R N (a) (b) Figure 2.2 (a) Leonardo da Vinci’s experiments. The force needed to move the blocks is independent of the contact area. (b) Notation for the Amontons–Coulomb laws. The Amontons–Coulomb laws The macroscopic laws governing the friction between two solids were determined experimentally using sliding blocks. A first experiment performed by Leonardo da Vinci is shown in Fig. 2.2(a). Three observations can be made on this device. 1. The force F T s needed to move the blocks is independent of the contact area and the same irrespective of whether the blocks are in a pile or placed one beside the other (Fig. 2.2(a)). 2. The force F T s linearly depends on the normal force (here the total weight of the blocks). 3. Once the blocks are sliding, the friction force F T d is smaller than the force F T s needed to start movement. These observations lead to the classical laws of solid friction, which were first written by Amontons in 1699 and further developed by Coulomb in 1785 (Coulomb, 1785). - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Learning Press(Publisher)

In 2008 scientists for the first time were able to move a single atom across a surface, and measure the forces required. Using ultrahigh vacuum and nearly-zero temperature (5 K), a modified atomic force microscope was used to drag a cobalt atom, and a carbon monoxide molecule, across surfaces of copper and platinum. Limitations of the Coulomb model The Coulomb approximation mathematically follows from the assumptions that surfaces are in atomically close contact only over a small fraction of their overall area, that this contact area is proportional to the normal force (until saturation, which takes place when all area is in atomic contact), and that frictional force is proportional to the applied normal force, independently of the contact area (you can see the experiments on friction from Leonardo Da Vinci). Such reasoning aside, however, the approximation is fundamentally an empirical construction. It is a rule of thumb describing the approximate outcome of an extremely complicated physical interaction. The strength of the appro-ximation is its simplicity and versatility – though in general the relationship between normal force and frictional force is not exactly linear (and so the frictional force is not entirely independent of the contact area of the surfaces), the Coulomb approximation is an adequate representation of friction for the analysis of many physical systems. When the surfaces are conjoined, Coulomb friction becomes a very poor approximation (for example, adhesive tape resists sliding even when there is no normal force, or a negative normal force). In this case, the frictional force may depend strongly on the area of contact. Some drag racing tires are adhesive in this way. However, despite the com-plexity of the fundamental physics behind friction, the relationships are accurate enough to be useful in many applications. Fluid friction Fluid friction occurs between layers within a fluid that are moving relative to each other. - No longer available |Learn more

- (Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- Academic Studio(Publisher)

In 2008 scientists for the first time were able to move a single atom across a surface, and measure the forces required. Using ultrahigh vacuum and nearly-zero temperature (5 K), a modified atomic force microscope was used to drag a cobalt atom, and a carbon monoxide molecule, across surfaces of copper and platinum. Limitations of the Coulomb model The Coulomb approximation mathematically follows from the assumptions that surfaces are in atomically close contact only over a small fraction of their overall area, that this contact area is proportional to the normal force (until saturation, which takes place when all area is in atomic contact), and that frictional force is proportional to the applied normal force, independently of the contact area (you can see the experiments on friction from Leonardo Da Vinci). Such reasoning aside, however, the approximation is fundamentally an empirical construction. It is a rule of thumb describing the approximate outcome of an extremely complicated physical interaction. The strength of the approximation is its simplicity and versatility – though in general the relationship between normal force and frictional force is not exactly linear (and so the frictional force is not entirely independent of the contact area of the surfaces), the Coulomb approximation is an adequate representation of friction for the analysis of many physical systems. When the surfaces are conjoined, Coulomb friction becomes a very poor approximation (for example, adhesive tape resists sliding even when there is no normal force, or a negative normal force). In this case, the frictional force may depend strongly on the area of contact. Some drag racing tires are adhesive in this way. However, despite the complexity of the fundamental physics behind friction, the relationships are accurate enough to be useful in many applications. Fluid friction Fluid friction occurs between layers within a fluid that are moving relative to each other. - Eugene D. Shchukin, Andrei S. Zelenev(Authors)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

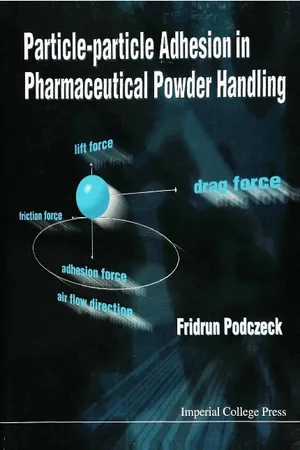

3 1 Surface Forces and Contact Interactions The properties of a contact between the particles of a solid phase depend on a combination of the properties of that solid phase, the media in the gap between the particles, and the interactions between the solid phase and the medium� To a great extent, these interactions are due to intermolec-ular forces acting at the interface between phases� Since s urface forces are one of the main subjects discussed in modern books on colloid and surface science, we will restrict ourselves only to a brief review of the subject relevant to physical-chemical mechanics� 1.1 PHYSICAL-CHEMICAL PHENOMENA AT INTERFACES Before turning to a discussion on particular interactions, it is worth reviewing the basic principles of the thermodynamics of surface forces and the concept of surface (or interfacial) free energy and of surface tension in particular� On an intuitive level, the concept of surface tension becomes apparent in the description of Dupré’s original experiment, in which one observes the stretching of a soap film, either in a bubble or on a frame (Figure 1�1)� Equilibrium is established when a force, F = 2 d σ , is applied to the mov-ing boundary, where d is the frame width, σ is the surface tension , and the numerical coefficient 2 implies that the film has two sides� Displacing the boundary by Δ l increases the film area by 2 d Δ l and requires that work equal to F Δ l is expended (Figure 1�1)� Per unit of the newly formed surface, this work is F Δ l /2 d Δ l = F /2 d = σ � Consequently, the meaning of σ now is specific surface free energy (units of work per unit surface area)� In a thermodynamic sense, the term “free” means that this (equilibrium) process takes place at constant temperature and volume� The identity of those two notions, that is, of the surface tension and the surface free energy, is true only for “common”- Fridrun Podczeck(Author)

- 1998(Publication Date)

- ICP(Publisher)

CHAPTER 2 BRIEF OVERVIEW OF THE THEORY OF FRICTION 2.1 Definition and Importance of Friction Forces Surfaces in contact to each other are held by forces directed normally to the interface (adhesion) and tangentially to the interface (friction). The latter be-come manifested if a relative displacement of the contacting surfaces is forced (Deryaguin et al. 1978a, pp. 380-381). This makes the friction phenomenon important for all powder handling processes, where particles move along a sur-face (for example powder flow through a hopper) or change their position in a powder bed (for example during mixing). It has been estimated, that about 5 % of the gross national product in the developed countries is wasted due to uncontrolled friction and wear (Persson 1995). However, friction can be advantageous, for example, when driving a car, where the design and the sur-face profile can influence the friction properties and hence the safety of driving (Tabor 1994). Friction should therefore not always be considered negatively. The friction force expresses itself as a force directed to oppose the velocity vector of the moving solid body. Friction forces can be divided into a static and dynamic type depending upon the absence or type of relative motion between the surfaces in contact. A finite force i. e. yield stress must be applied to initiate motion, and friction then arises from a transfer of energy between the surfaces in contact (Yoshizawa et al. 1993). The static friction force is very often larger than dynamic friction forces due to sliding or rolling (Bowden and Tabor 1954, p. 105; Heslot et al. 1994). Sliding friction is characterized by a slippage of two surfaces over each other. Rolling friction, however, does not involve any slippage, but can be described as a series of adhesion and detachment processes (Deryaguin et al. 1978a, p. 280), which causes one of two bodies in contact to roll over the surface of the second body.- eBook - PDF

- Joaquim A. Batlle, Ana Barjau Condomines(Authors)

- 2022(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

On the one hand, it is one of the so-called fundamental interactions in physics: It is not the result of any underlying phenomena which combine and yield that interaction; in other words, its formulation is not phenomenological. On the other hand, it is the only interaction “at a distance” (that is, between particles separated in space without any intermediate element connecting them). All other interactions between particles that will be formulated in this section call for intermediate elements: elements connected to those particles and whose mass is significatively smaller than that of the particles. In a first approach, then, the mass of those elements can be neglected, and the force exerted by one particle at the endpoint of the element is equal, though with opposite sign, to that exerted by the other particle at the other endpoint. In other words, those two forces fulfill Newton’s 16 Particle Dynamics third law, and can be understood as an action–reaction pair of forces between the particles (Fig. 1.10). The usual intermediate elements found in mechanical systems are springs, dampers, and linear actuators. Interactions between particles through those elements are the result of underlying phenomena whose overall effect on the particles is formulated at a phenomenological level through empirical models. Gravitational Force Newton’s law of universal gravitation states that two particles P and Q attract each other with a force directly proportional to the product of their masses and inversely proportional to PQ 2 (Fig. 1.11): F grav P$Q ¼ G 0 m P m Q PQ 2 ¼ G 0 m P m Q ρ 2 : (1.11) Strictly speaking, m P and m Q in Eq. (1.11) are the gravitational masses of the particles. They are conceptually different from the inertial masses, but there is no empirical evidence so far that they should differ, so they will be treated as one same thing.

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.