Psychology

Vestibular Sense

The vestibular sense is the body's ability to sense and maintain balance and spatial orientation. It is primarily located in the inner ear and provides information about head position, movement, and acceleration. This sense helps individuals to navigate their environment and maintain stability during various activities.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

10 Key excerpts on "Vestibular Sense"

- eBook - PDF

Vision Rehabilitation

Multidisciplinary Care of the Patient Following Brain Injury

- Penelope S. Suter, Lisa H. Harvey, Penelope S. Suter, Lisa H. Harvey(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

ROLE OF THE VESTIBULAR SYSTEM The vestibular system is responsible for (1) detecting linear and angular head movement and head position in space; (2) assisting gaze stabilization of the visual field; (3) main-taining balance and postural control; and (4) providing spatial orientation or percep-tion of body movement. The vestibular system continually makes adjustments with the cooperation of interacting systems in response to movements. The primary role of the The Vestibular System 305 vestibular system is to provide the central nervous system (CNS) with information to regulate posture and to coordinate eye and head movements. 5 The system represents our sense of balance or equilibrium and is often referred to as the “sixth sense.” 6,7 PRIMORDIAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR SYSTEM Before 5 weeks gestation, the embryonic beginnings of the human peripheral vestibular and auditory structures emerge as one unit called the otocyst . At 5 weeks gestation, differentiation of the two structures occurs with the vestibular organ developing more rapidly than the hearing (cochlea) organ. This may be an indication of the vestibular sys-tem’s important role in the development of other portions of the nervous system. Between 7 and 14 weeks gestation, the semicircular canals (SCC or canals) and receptor hair cells form and begin to attract neurons of the vestibular nerve to synapse (connect) with them. The tiny receptor hair cells are the common sensory receptors in the vestibular and cochlear organs. Some vestibular neurons will grow toward the brainstem. By 12 weeks gestation, reflexive eye movements respond to changes in head position. 5,6,8 By the last week of the first trimester, the vestibular nerve has become the first fiber tract in the brain to begin myelination. Myelin is a white lipid substance that insu-lates axons to promote rapid transmission of electrical signals throughout the entire nervous system. - eBook - PDF

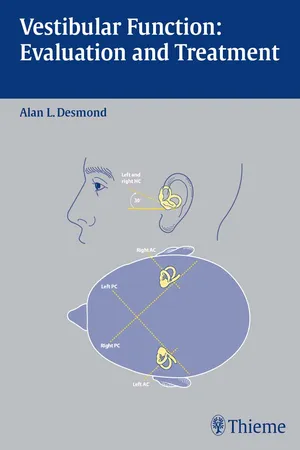

Vestibular Function

Clinical and Practice Management

- Alan L. Desmond(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Thieme(Publisher)

♦ Normal Function of the Vestibular System The primary role of the balance system is to allow us to interact and maintain contact with our sur-roundings in a safe, efficient manner. As we move through our environment, information is gathered through the visual, somatosensory, and Vestibular Senses and sent to the brainstem for integration and finally to the cortex for perception and processing ( Fig. 2.1 ). The visual and somatosensory refer-ence information is constantly changing as a function of movement, but the vestibular reference— gravity—is unchanging. As long as the information arriving from these three sources is predictable and nonconflicting, equilibrium is maintained and there is little thought regarding balance. When a sensory conflict occurs, the brain must efficiently and quickly (reflexively) adjust the level of priority given to the conflicting incoming information, or a sensation of imbalance may occur. Be-cause the known constant in the mix is gravity, humans tend to rely more on vestibular information for maintenance of dynamic balance than they do on proprioceptive or visual information (when the peripheral vestibular system is damaged, this may change). Allum and Pfaltz (1985) hypothesized that vestibular information contributes 65% to dynamic body stability; vision and proprioception providing less of a contribution. Standing balance, however, does not rely primarily on vestibular information. Colledge et al. (1994) and Hobeika (1999) report that proprioception is the major contributor to standing balance; however, when proprioceptive input is not helpful (i.e., moving or compliant surface), vision becomes the primary source of information. In summary, the balance system is dynamic and quickly responds to changes in visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive feedback. - Dorita S. Berger(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Jessica Kingsley Publishers(Publisher)

Both vestibular and proprioceptive systems are interoceptive (internal monitoring) processes receiving and transmitting to the brain sensory information derived in a variety of ways. The third system interacting with the two above is the tactile system, which processes touch sensations from external sources (skin) and internal sources (including the tongue). The senses of taste and smell are tactile-system relatives; smell receptors are connected directly to areas of the amygdala and hypothalamus. Visual and auditory systems come into play at higher levels of brain processing. Using the vestibular, proprioceptive and tactile systems, the whole brain amalgamates incoming and outgoing information to define the world. The cooperative, simultaneous workings of the five basic systems coalesce to provide the myriad of functions typical to human behaviors. The vestibular system Gravity is the human being’s first problem! As soon as the infant floats out of the womb it is confronted by gravitational pressures. The DNA information (inscriptive adaptation) is in place to inform the brain how to cope with the sensation of falling, and how to sustain itself against gravitational forces. You will notice a newborn immediately stiffen and thrust both arms into space as a corrective reaction to the sensation of being pulled downward. This is the work of the vestibular system. The vestibular system is a highly complex operation that interprets body position and spatial orientation based on the position of the head.For instance, how does the brain know that the tower of Pisa is leaning, and not you? Because, among other things, the brain knows the exact position of your head based on sensations flowing from vestibular receptors within the ears: hair cells (cristae) located in the semicircular canals (there are three), the utricle and the saccule of the vestibular labyrinth (Fisher 1991)- eBook - PDF

- Orhan E. Arslan(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

363 15 Vestibular System The vestibular system is a special somatic afferent system that maintains the orientation in the three dimensions, fixa-tion of gaze during head rotation, and control of muscle tone. In order to accomplish these diverse activities, generated impulses at the receptor level are carried by the vesibular nerve to the cerebellum and the vestibular nuclei. Projections from these nuclei eventually reach the extraocular motor nuclei, cerebellum, and spinal cord. PERIPHERAL VESTIBULAR APPARATUS Vestibular receptors are contained in the inner ear within the semicircular canals and the vestibule. These receptors convey vestibular inputs through the dendrites of the bipolar neurons of Scarpa’s ganglia to the cerebellum and brainstem. Massive projections from the brainstem to subcortical and spinal neurons allow the generated impulses to exert influ-ences on vast areas of the nervous system. S EMICIRCULAR C ANALS Semicircular canals (Figure 15.1) are three in number, consisting of the anterior (superior), posterior, and lateral (horizontal) canals. They are unequal in length, form an incomplete circle, and are perpendicular to each other, enclos-ing the endolymph-filled membranous semicircular ducts. They contain the perilymph-filled perilymphatic spaces separated from the endolymph-filled semicircular ducts. The anterior (superior) semicircular, a vertical canal, lies inferior to the arcuate eminence and is oriented horizontally to the axis of the petrous temporal bone. The ampulla of this canal opens into the upper and lateral part of the vestibule. The lateral (horizontal) canal is directed horizontally posteriorly and laterally, joining the vestibule just inferior to the opening of the ampullary end of the superior semicircular canal and superior to the fenestra vestibuli (oval window). The poste-rior semicircular, a vertical canal, is positioned parallel to the posterior surface of the petrous temporal bone. - eBook - PDF

Vestibular Function

Evaluation and Treatment

- Alan L. Desmond(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Thieme(Publisher)

2 Function and Dysfunction of the Vestibular System Normal Function of the Vestibular System The primary role of the balance system is to allow humans to interact and maintain contact with their surroundings in a safe, efficient manner. As humans move through their environment, information is gathered through their visual, somatosensory, and Vestibular Senses and sent to the brain stem for integration and finally to the cortex for perception and processing (Fig. 2 / 1). The visual and somatosensory reference information is constantly changing as a function of movement, but the vestibular reference * / gravity * / is unchanging. As long as the information arriving from these three sources is predictable and nonconflict-ing, equilibrium is maintained and there is little thought regarding balance. When a sensory conflict occurs, the brain must efficiently and quickly (reflexively) adjust the level of priority given to the conflicting incoming information, or a sensation of imbalance may occur. Because the known constant in the mix is gravity, humans tend to rely more on vestibular information for maintenance of dynamic balance than they do on proprioceptive or visual information (when the peripheral vestibular system is damaged, this may change). Allum and Pfaltz (1985) hypothesized that vestibular information contributes 65% to dynamic body stability; vision and proprioception provide less of a contribution. Standing balance, however, does not rely primarily on vestibular information. Colledge et al. (1994) and Hobeika (1999) report that proprioception is the major contributor to standing balance; however, when proprioceptive input is not helpful (i.e., moving or compliant surface), vision becomes the primary source of information. In summary, the balance system is dynamic and quickly responds to changes in visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive feedback. - eBook - ePub

The Sage Handbook of Cognitive and Systems Neuroscience

Neuroscientific Principles, Systems and Methods

- Gregory J. Boyle, Georg Northoff, Aron K. Barbey, Felipe Fregni, Marjan Jahanshahi, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Barbara J. Sahakian, Gregory J. Boyle, Georg Northoff, Aron K. Barbey, Felipe Fregni, Marjan Jahanshahi, Alvaro Pascual-Leone, Barbara J. Sahakian, Author(Authors)

- 2023(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications Ltd(Publisher)

22 Vestibular Processing in Cognition Paul C. J. TaylorIntroduction

Although parts of the vestibular peripheral organs were described in the seventeenth century, Antonio Scarpa provided the first detailed description of the anatomy of the vestibular organs in 1789. Subsequently, in 1842, Marie Jean Pierre Flourens lesioned the semicircular canals of pigeons and reported that movements became uncoordinated in particular planes, but concluded that their role was ultimately in audition. Jan Evangelista Purkinje studied vertigo in 1820, noting like others before him, that spinning people on rotating chairs lead to systematic eye movements, but he concluded that it was predominantly cerebellar. From the 1870s onward, researchers started to suggest that the vestibular organs play a role in balance. For example, Ernst Mach noticed that the semicircular canals were insensitive to linear forces, although he did not believe in a role for the endolymph's motion, but rather its pressure. William James noted that out of over 500 deaf mutes tested, more than one-third seemed immune to dizziness after spinning, unlike all but one out of 200 of his Harvard academic colleagues.The anatomy of the vestibular sensory organs provides important clues and constraints to vestibular function – core to which is not balance per se, but rather, detecting how the head is moving. The structural blueprint of the vertebrate vestibular system has been largely conserved across four hundred million years of evolution (Straka and Baker, 2013). Within each inner ear are three semicircular canals and two other organs (otoliths), making 10 sensory organs, with five on each side. These tiny bodies are all encapsulated within the floor of the skull (Figure 22.1 ), reducing any timelag between head movement and sensation.Figure 22.1 - eBook - PDF

- David R Soderquist(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- SAGE Publications, Inc(Publisher)

SENSORY PROCESSES The Vestibular System The Vestibular System little nausea and dizziness often occurs in the modern world. A day at the lake sailing in your friend’s new boat sounds like a great idea. Some-times, however, an adventure becomes a misadventure. State and county fairs have their unique place in this respect. The amusement rides are called, for obvious reasons, by unique monikers—for example, The Hammer, The Whip, The Octopus, The Belly-Snapper, and of course, The Roller Coaster— are named appropriately. Whether or not you are among the thousands of people who get thrills and surges of euphoria on these stimulating rides is your concern. Without any doubt, the rides have to be classified as exciting. It just depends on how excited you want to get. What is important here is that our everyday living involves the silent vestibular system. Whether you have experienced carnival rides or not, you can imagine the nausea that could occur with these activities. The cause of the queasy feelings that some people get, however, are examined more fully as we examine the Vestibular Sense, sometimes referred to as the sense of balance. It is important to note, incidentally, that to refer to the Vestibular Sense as the sense of balance is restrictive. The Vestibular Sense extends beyond just postural balance. It is a complex system intimately related to eye movements, postural reflexes, head motion, and gravitational balance. Unlike the other sensory systems we have discussed, the vestibular activ-ity does not usually enter prominently in consciousness unless a disruption occurs in its smooth operation. Consider, for example, the intricate coordi- nation required when you look at the wall clock as you are leaving the class-room. A stable visual perception requires that you automatically coordinate head and eye movement while simultaneously maintaining your balance and posture without stumbling, leaning, tilting precariously, or falling flat on your face. - eBook - ePub

Attention, Balance and Coordination

The A.B.C. of Learning Success

- Sally Goddard Blythe(Author)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- Wiley(Publisher)

Affective symptoms of depression and anxiety can also develop: the former as a result of feeling generally unwell and out of touch with the world; the latter because the emotional sense of security is partly based on physical stability. If vestibular dysfunction is extreme, it can lead to loss of self-reliance, self-confidence, and self-esteem. It is therefore hardly surprising that a child with undiagnosed vestibular dysfunction may struggle to achieve in the classroom and may also develop problems of a behavioural nature.To summarize, the vestibular system is involved in the filtering and fine-tuning of all sensory information before it enters the brain – light, sound, motion, gravitational energy, air pressure, and temperature. It is responsible for controlling and for fine-tuning our vision; hearing; balance; sense of motion, altitude, and depth; sense of smell; sense of time; sense of direction; and anxiety/depression levels as mentioned above. Therefore, any one or a cluster of these processes can be affected when suffering from an inner ear dysfunction. Specific learning difficulties and perceptual problems are only a few of the possible symptoms that can arise from a dysfunction of the inner ear. Because the functioning of the vestibular system is so closely linked via the reticular activating system to the functioning of the autonomic nervous system, inner ear dysfunction can also have a significant impact on emotions and on behaviour at any time through the lifespan.REFERENCES1 Hippocrates. In: Hippocrates VII . 1994. Epidemics 2/4–7. The Nature of Man . Trans. Wesley D Smith. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.2 Golding J. 2007. Motion sickness: friend or foe? The Inaugural Lecture of John Golding . March 2007, London.3 Cox JM. 1804. Practical Observations in Insanity , pp. 106. Baldwin and Murray, London.4 Hallaran WS. 1810.An Enquiry into the Causes Producing the Extraordinary Addition to the Number of Insane, Together with Extended Observations on the Care of Insanity: with Hints as to the Better Management of Public Asylums. Edwards & Savage, Cork.5 Purkinje J. 1820. Beiträge zur näheren Kenntniss des Schwindels aus heautognostischen Daten. Medicinische Jahrbücher des Kaiserlich-königlichen Österreichischen Staates - eBook - PDF

Space and Life

An Introduction to Space Biology and Medicine

- Hubert Planel(Author)

- 2004(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

8 The Vestibular Apparatus and Balance System The third organ disturbed under weightlessness is the vestibular apparatus. Although it plays an essential role in everyday life, few people are aware of its existence. This is easily explained: whereas human beings are continuously made conscious of the world around them through sight, hearing, olfaction and touch detectors, the vestibular apparatus is an automatic system, sending subconscious information to the brain. Only pathological manifestations, for instance vertigo or motion sickness caused by a rocking ship, remind us of its presence. The vestibular apparatus has a complex role to play. It is a part of the sensory motor system that controls body orientation, locomotion, accurate movement and eye motion. This control requires information coming not only from the vestibular system, but also from vision and proprioception (Figure 25). While vision can be considered to be independent from gravity, proprioception and, to a greater extent, the vestibular apparatus are affected by gravity. This explains why astronauts, as we shall see later, not only experience sickness but also many types of other disturbances. PROPRIOCEPTION Proprioception is the function that allows the brain to receive information from muscles, tendons and joints. Touch receptors located near the skin surface also participate in proprioception and body balance. That is the case for receptors located in the sole of the foot. In an upright position, body weight exerts a pressure on this area, thus stimulating nerve endings and subconsciously informing the brain that the body is upright. In the same way, nerve fibers in the region of the buttocks confirm that the body is seated. Proprioceptive signals are also received from tendons, joints and muscles. The tendons contain Golgi corpuscles, which are small organelles, a few tenths of a millimeter in length, connected to nerve fiber endings. - eBook - ePub

- Alain Berthoz, Giselle Weiss(Authors)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Harvard University Press(Publisher)

The brain has to reinterpret the information transmitted by these receptors to be able to compare them with sensations from other proprioceptive and visual receptors. Finally, let me reiterate a point that is often poorly understood: vestibular receptors are not only sensors of movement. They also signal immobility. Indeed, these sensors have a basic discharge whose lack of variation is interpreted by the brain as immobility. They are essential for assessing what is called the subjective vertical (see Chapter 4). Although they make it possible to recognize head movements, vestibular receptors alone are not enough, because of the ambiguous information they provide. For example, they cannot distinguish between acceleration of the head in one direction and braking in the other direction. Tactile or visual information helps to resolve this ambiguity. This clearly shows how perception requires cooperation among the senses. Another ambiguity that has already been mentioned is the distinction between the angle of tilt of the head and linear acceleration. This is known as the problem of gravito-inertial differentiation, and I will refer to it again in Chapter 13. To this problem nature found a solution, called frequential filtering. It consists in separating the two components of movement at the level of the first sensory relays, in the so-called vestibular nuclei and perhaps even at the level of the fibers that connect the receptors to these first relays. In fact, in the vestibular nuclei there are two kinds of neurons. Some respond especially to slow variations in acceleration, but are indifferent to rapid movements. The solution is an elegant one, because detecting the angle of tilt of the head involves slow neurons, and detecting acceleration involves rapid neurons. Others are highly activated by very rapid movements of the head and only slightly by slow movements

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.