Technology & Engineering

Viscoelasticity

Viscoelasticity refers to the property of materials that exhibit both viscous (flowing) and elastic (rebounding) behavior when subjected to stress. This means they can deform and return to their original shape over time. Viscoelastic materials are commonly found in products like adhesives, gels, and certain plastics, and their behavior is important in various engineering applications, such as in damping vibrations and shock absorption.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

Related key terms

1 of 5

12 Key excerpts on "Viscoelasticity"

- eBook - PDF

- Robert J. Young, Peter A. Lovell(Authors)

- 2011(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

487 20 Viscoelasticity 20.1 INTRODUCTION A distinctive feature of the mechanical behaviour of polymers is the way in which their response to an applied stress or strain depends upon the rate or time period of loading. This dependence upon rate and time is in marked contrast to the behaviour of elastic solids such as metals and ceramics that, at least at low strains, obey Hooke’s law such that the stress is proportional to the strain and independent of loading rate. On the other hand, the mechanical behaviour of viscous liquids is time dependent. It is possible to represent their behaviour at low rates of strain by Newton’s law whereby the stress is proportional to the strain-rate and independent of the strain. The behaviour of most polymers can be thought of as being somewhere between that of elastic solids and viscous liquids. At low temperatures and high rates of strain they display elastic behaviour, whereas at high temperatures and low rates of strain they behave in a viscous manner, flowing like a liquid. Polymers are, therefore, termed viscoelastic as they display aspects of both viscous and elastic types of behaviour. Polymers used in engineering applications often are subjected to stress for prolonged periods of time, but it is not possible to know how a polymer will respond to a particular load without a detailed knowledge of its viscoelastic properties. There have been many studies of the viscoelastic proper-ties of polymers and several textbooks written specifically about the subject of Viscoelasticity. The intention here is to give a brief introduction to what is a vast subject and to leave the reader to consult more advanced texts for further details. The exact nature of the time dependence of the mechanical properties of a polymer sample depends upon the type of stress or straining cycle employed. - Rajinder Pal(Author)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

199 13 Viscoelastic Behavior of Composites 13.1 INTRODUCTION A purely elastic material (for example, Hookean solid) differs widely in its defor-mational characteristics from a purely viscous material (for example, Newtonian fluid). The stress in a purely elastic material is a function only of the instantaneous magnitude of deformation (strain) whereas in a purely viscous material, the stress is a function only of the instantaneous rate of deformation. Also, purely elastic materi-als return to their natural or undeformed state upon removal of applied loads whereas purely viscous materials possess no tendency at all for deformational recovery. The term “viscoelastic” implies the simultaneous existence of viscous and elastic char-acteristics in a material. Thus, a material behavior that incorporates a blend of both viscous and elastic characteristics is called viscoelastic behavior. Many materials, including composites, exhibit viscoelastic behavior. They flow under the influence of applied stresses, unlike purely elastic materials, which exhibit a constant strain and no flow. Upon removal of the applied stress, some of their defor-mation is gradually recovered; that is, they exhibit elastic recovery unlike purely viscous materials, which exhibit no recovery at all. The term “linear Viscoelasticity” implies the study of viscoelastic effects in a small strain region where strain varies linearly with stress (doubling the stress will double the strain). Among the various techniques available to study the linear viscoelastic behavior of materials, oscilla-tory testing at small strain amplitudes is very popular. The material is subjected to oscillatory strain, and its stress response is monitored. The material could be sub-jected to either oscillatory normal strain or oscillatory shear strain. For purely elastic materials, stress is in phase with the strain. For viscoelastic materials, there occurs a lag between the stress and strain.- eBook - PDF

- Kam-tim Chau(Author)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER SEVEN Viscoelasticity and Its Applications 7.1 INTRODUCTION Deformation and stress in certain materials are known to vary with time even though the external excitations, regardless of displacement or loads, are constant with time. In terms of dynamic problems, vibrations in solids are known to damp with time. In a sense, there appears a viscous effect in the solid. A solid can exhibit such a time effect but remains elastic. In reality, there may be some permanent deformation remains in the body, depending on the magnitude of the excitations. The theory of viscoplasticity was introduced in Section 5.17. However, if such permanent deformation is relatively small, we can model it as viscoelastic. That is, when the excitation is removed, the body returns to its original shape and size. Theoretical formulation that deals with such a viscoelastic body is called Viscoelasticity . There are two extremes of Viscoelasticity: if viscous response is negligible, the solid is purely elastic; if the elastic response is negligible, the material is a viscous fluid. Time-dependent creeping has been reported in both rock and soil slopes, and deformation in excavated tunnels is often found to increase with time. There have been many examples of delayed geomechanical failure after loadings have been applied. Therefore, Viscoelasticity finds its application in many applications in geotechnical problems. A special feature of viscoelastic solids is that their present state of deformation cannot be determined if their entire loading history is not known. In other words, a viscoelastic body appears to have memory of its entire past. Because of this the deformation of viscoelastic solid at time t must be summed from its total loading history. In the case of stress relaxation (i.e., imposing strain as a controlling parameter), the current stress is a function of the current strain as well as its entire strain history. - eBook - PDF

- Mohamed Fathy El-Amin(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

The mechanical performance arises from the viscoelastic features of the material [1]. In other words, mechanical features are time dependent, whereas perfectly elastic deformation and perfectly viscous flow are idealiza‐ tions that are approximately reached in some limited conditions. Viscoelastic materials present, under mechanical stress, combined characteristics of these two behaviors, a “fading © 2016 The Author(s). Licensee InTech. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. memory”, partial recovery, energy dissipation, etc. This type of dependence can be linear (stress – strain dependence is a straight line with a single slope) or nonlinear (stress – strain dependence presents many slopes) [2, 3]. Among the compounds with pronounced Viscoelasticity, polymers are the most important in rubber and plastic industries [4, 5]. Their viscoelastic properties influence not only the mechanical reliability of the final products of these industries, but also the efficiency of processing methods at intermediate stages of production. In most cases, the designer aims to maintain the elastic deformations under a critical limit. The peculiar viscoelastic features of polymers arise from the complex dynamics of flexible chains [6]. For instance, above the glass transition temperature ( T g ), the response of these materials to mechanical perturbation forces entails several types of molecular motions. The large freedom in the spatial arrangement of macromolecular compounds allows various types of motion according to the time and spatial scales. At big scales, the polymer chains present unique dynamic features that are not found in low-molecular-weight materials. - eBook - PDF

Viscoelasticity

From Theory to Biological Applications

- Juan de Vicente(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- IntechOpen(Publisher)

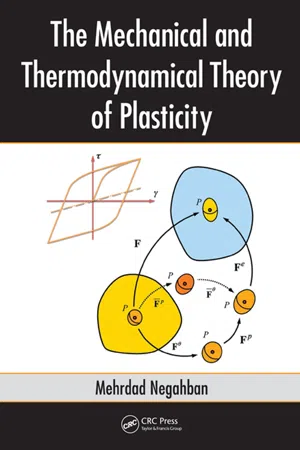

Such a study will contribute to the construction of molecular theory for the Viscoelasticity in amorphous materials. In this chapter, some examples of viscoelastic nature of biological materials and then their relevance to the structure would be presented. In some cases, a mechanistic model for the Viscoelasticity will be presented. As measuring method varies depending on the modulus value of the specimens, the various methods used in studying viscoelastic properties of biological materials will be illustrated. 2. A Brief introduction to Viscoelasticity 2.1. Introduction to elasticity and viscosity Elasticity is a material property that generates recovering force at an application of an external force to deform the material. When an external force is applied to a material and the material is in an equilibrium deformation, the external force is balanced by an inner force. The inner force is the recovering force. The recovering force divided by the cross sectional © 2012 The Author(s). Licensee InTech. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Viscoelasticity – From Theory to Biological Applications 100 area that the external force is working on is defined as stress, σ . Suppose the material is initially in a shape of rod of length L 0 and cross-sectional area, A 0 . The force is applied to the length direction and the length after the deformation is L. The deformation is generally normalized as, 0 0 , L L ε L (1) where is called the engineering strain or the Caushy strain. This is used for small deformations. For small strains, a Hookean relation, σ ε (2) has been known to hold. The proportionality factor is defined as a modulus and the modulus is a material’s constant. - Mehrdad Negahban(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Chapter 13 Viscoelastic solids Viscoelastic materials are those that show stress relaxation at all magnitudes of loading, even at very small loads. Models normally describing Viscoelasticity show rate-dependent response and even yielding like behavior without the use of a yield function. As such, they normally are characterized as a different class of material response. The typical characteristic of the response of a nonlinear viscoelastic material is shown in Figure 13.1 for the flow and relaxation of poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) at 140 o C , which is a temperature in the rubbery response range of this material. The figure shows constant strain rate loading, starting from an initially rigid response followed by what looks like yielding and then flow. For a viscoelastic material, the point of yielding depends on the loading rate as shown in Figure 13.2 for PMMA at 120 o C . For the test shown in Figure 13.1 , at the end of the constant strain rate loading, the sample is held at constant strain, which results in stress relaxation to an equilibrium stress other than zero. This nonzero stress is called the back-stress and is shown in Figure 13.3 for PMMA at 140 o C . As can be seen, not only does the stress relax to the the back-stress, but when it is at values below it one will see a stress buildup to the equilibrium. Mechanical analogs to describe the phenomenon seen in Viscoelasticity are constructed from springs and viscous dampers, such as is shown for a standard linear solid in Figure 13.4 . For a nonlinear response, the components of these analogs can be nonlinear. We start the chapter by looking at one-dimensional linear and nonlinear viscoelastic response. The most common model for linear Viscoelasticity is called the “standard linear solid,” which will be discussed first; its mechanical analog is shown in Figure 13.4 . This is then generalized to create a viscoelastic model constructed from a continuous series of standard linear solids put in parallel.- eBook - PDF

The Rheology Handbook

4th Edition

- Thomas G. Mezger(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Vincentz Network(Publisher)

Viscoelastic behavior 106 When performing rheological tests on biological materials, it is important to take into conside-ration that these kinds of materials usually cannot be deformed evenly in the entire shear gap due to their mostly inhomogeneous structures and superstructures, related to macroscopic structure sizes in the range of around 0.1 to 1mm. This may lead to conditions at which the reproducibility of test results will be poor, and therefore, these kinds of materials often cannot be analyzed scientifically in terms of absolute values (see also Chapter 3.3.4.3d: inhomogene-ous, “plastic” behavior). Summary: Behavior of viscoelastic solids Desired behavior of viscoelastic materials can be obtained only if the viscous and elastic por-tions are in a well-balanced ratio. Example: Bamboo Required behavior is given for bamboo bars only if both, flexibility (viscous behavior) and rigidity (elastic behavior) are present, showing the right mixture of both components. Only in this case, the material may show the optimal (viscoelastic) behavior. By the way: Also in East Asian nature philosophy, bamboo is an illustrative example to characterize balanced behavior or properties. For “Mr. and Ms. Cleverly” 5.3 Normal stresses This chapter is intended for giving merely in a nutshell some basic information on normal stress tests and on the corresponding terminology in this field. If a viscoelastic material is deformed, there are not only one-dimensional forces or stresses acting in the direction of the deformation. In fact, there is always a state of three-dimen-sional deformation . This can be illustrated using a (3 ⋅ 3) tensor (see also Chapter 13.2: A.L.Cauchy , 1827 [71] , and J.C. Maxwell , 1855 [245] ). It contains nine values, which can be dis-played in a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system. In order to explain this, you can imagine the behavior of a cube-shaped volume element of our test material. - eBook - PDF

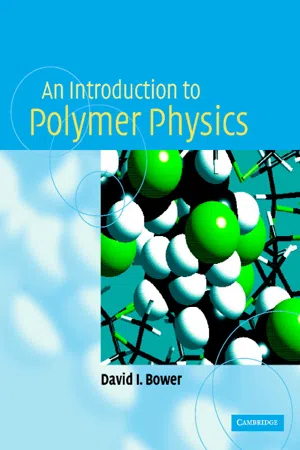

- David I. Bower(Author)

- 2002(Publication Date)

- Cambridge University Press(Publisher)

Chapter 7 Mechanical properties II – linear Viscoelasticity 7.1 Introduction and definitions 7.1.1 Introduction In section 6.1 it is pointed out that, at low temperatures or high frequen-cies, a polymer may be glass-like, whereas at high temperatures or low frequencies it may be rubber-like. In an intermediate range of temperature or frequency it will usually have viscoelastic properties , so that it undergoes creep under constant load and stress-relaxation at constant strain. The fundamental mechanisms underlying the viscoelastic properties are various relaxation processes, examples of which are described in section 5.7. The present chapter begins with a macroscopic and phenomenological discus-sion of linear Viscoelasticity before returning to further consideration of the fundamental mechanisms. Consider first the deformation of a perfect elastic solid . The work done on it is stored as energy of deformation and the energy is released com-pletely when the stresses are removed and the original shape is restored. A metal spring approximates to this ideal. In contrast, when a viscous liquid flows, the work done on it by shearing stresses is dissipated as heat. When the stresses causing the flow are removed, the flow ceases and there is no tendency for the liquid to return to its original state. Viscoelastic properties lie somewhere between these two extremes. An isotropic perfectly elastic solid obeys equation (6.5) or ' ¼ G ð 7 : 1 Þ if ' is the shearing force and the shearing angle is (see fig. 7.1(a)), whereas a perfect Newtonian liquid obeys the equation (see fig. 7.1(b)) ' ¼ d d t ð 7 : 2 Þ where is the viscosity of the liquid. The simplest assumption to make about the behaviour of a viscoelastic solid would be that the shear stress depends linearly both on and on d = d t , i.e. that 187 ' ¼ G þ d d t ð 7 : 3 Þ This is essentially the result obtained for one of the simple models for Viscoelasticity to be considered below. - eBook - PDF

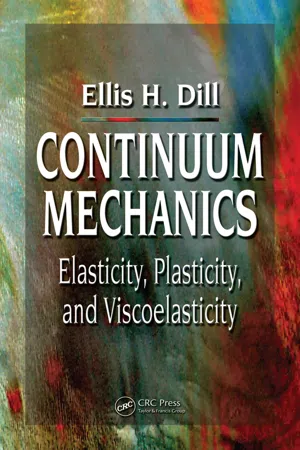

Continuum Mechanics

Elasticity, Plasticity, Viscoelasticity

- Ellis H. Dill(Author)

- 2006(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

213 5 Viscoelasticity 5.1 LINEAR Viscoelasticity Elastic materials are those for which stress is proportional to strain. A typical example of elastic behavior is provided by the ideal spring for which force (stress) is pro-portional to displacement (strain). The ideal spring (Fig. 5.1.1) can be used to model the general behavior of elastic materials in the following way. We have seen that an isotropic material is completely characterized by giving separately the constitutive law for volumetric strain and for distortion. For a linear elastic isotropic material, we found that deviatoric stress (5.1.1) and the deviatoric strain (5.1.2) are related by , (5.1.3) and that the mean stress is related to the volumetric strain by (5.1.4) FIGURE 5.1.1 Spring model. s 1 = τ − τ 1 3 ( ) tr e 1 = ε − ε 1 3 ( ) tr s e = µ 2 σ = tr / τ 3 ε = tr ε σ ε = K . 2 e s s µ 214 Continuum Mechanics These relations can be also be obtained by applying the spring model (Fig. 5.1.1) to each mode of deformation. The distortional strain is 2 e and the corresponding spring constant is µ. The mean stress is σ , the volumetric strain is ε , and the spring constant for dilatation is K. The two equations can then be combined by using the definition of the deviatoric components to get the single constitutive relation of the linear elastic isotropic material: , (5.1.5) where . (5.1.6) The spring is regarded as having no mass, so that instantaneous changes (jumps) in strain are possible: , (5.1.7) where (5.1.8) denotes the jump change in any function f ( t ). Viscous fluids, on the other hand, have a part of the stress that is proportional to the rate of strain. A typical example of a mechanism that exhibits such behavior is the shock absorber or damper mechanism (Fig. 5.1.2) for which force (stress) is proportional to velocity (strain-rate). When the distortion is modeled by such a mechanism, we have (damper), (5.1.9) where η is called the shear viscosity. - eBook - PDF

Polymers

Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials, Third Edition

- J.M.G. Cowie, Valeria Arrighi(Authors)

- 2007(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

Both laws can prove useful under these circumstances. In many cases, a material may exhibit the characteristics of both a liquid and a solid, and neither of the limiting laws will adequately describe its behavior. The system is then said to be in a viscoelastic state . A particularly good illustration of a viscoelastic material is provided by a silicone polymer known as “bouncing putty.” If a sample is rolled into the shape of a sphere, it can be bounced like a rubber ball, i.e., the rapid application and removal of a stress causes the material to behave like an elastic body. If, on the other hand, a stress is applied slowly over a longer period the material fl ows like a viscous liquid, and the spherical shape is soon lost if left to stand for some time. Pitch behaves in a similar, if less spectacular, manner. 346 Polymers: Chemistry and Physics of Modern Materials 13.2 THE FIVE REGIONS OF VISCOELASTIC BEHAVIOR The physical nature of an amorphous polymer is related to the extent of the molecular motion in the sample, which in turn is governed by the chain fl exibility and the temperature of the system. Examination of the mechanical behavior shows that there are fi ve distinguishable states in which a linear amorphous polymer can exist, and these are readily displayed if a parameter such as the elastic modulus is measured over a range of temperatures. The general behavior of a polymer can be typi fi ed by results obtained for an amorphous atactic polystyrene sample. The relaxation modulus E r was measured at a standard time interval of 10 s and log 10 E r is shown as a function of temperature in Figure 13.1. Five distinct regions can be identi fi ed on this curve as follows: 1. The glassy state: This is section A to B lying below 363 K, and it is characterized by a modulus between 10 9.5 and 10 9 Nm –2 . - Kevin L. Ong, Scott Lovald, Jonathan Black(Authors)

- 2014(Publication Date)

- CRC Press(Publisher)

2. At high strain rates, the material appears elastic and brittle, with no plastic region. A number of materials behave very much like this imaginary exam-ple, including fresh saltwater taffy and the silicone “rubber” used as a hand-exercising material. σ ε Increasing strain rate FIGURE 4.1 Stress–strain curves for a viscoelastic material. Viscoelasticity 79 Although a broad variety of different viscoelastic behaviors is pos-sible, all such solid materials share these general properties of appearing plastic (or viscous) and ductile at low strain rates and elastic and brittle at high strain rates. Thus, the derivation of the term viscoelastic is both obvious and mnemonic. Models The variety of viscoelastic behaviors that are observed in real materials do not relate in an easy, generic way to types of materials as do the vari-ous shapes of simple stress–strain curves for elastic–plastic materials (see Chapter 3). Additionally, these behaviors are not related simply and directly to the bond types present in the material but are related more closely to details of molecular structure and arrangement and to larger-scale aspects of material organization. To deal with these problems, it has become the practice to analyze the behavior of viscoelastic materials as if they were composed of arrays of small, simple mechanical elements connected together with pins and tie rods. This is an intellectual exercise; the model elements used in this approach generally have no close correspondence to physical parts of the actual material. However, when taken together, the stress–strain behavior of these model elements mirrors that of the actual material. In addition, when formal mathematical descriptions of stress–strain behavior are required, it is possible to generate them very quickly from these model elements, each of which has a very simple mathematical description. There are three principal model elements (also called bodies ) used to construct viscoelastic models.- Jonathan F. Stebbins, Paul F. McMillan, Donald B. Dingwell(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- De Gruyter(Publisher)

In the linear regime simple Hookean physics can be used to describe the relationship between stress, strain and strain-rate. The modulus M of a material is the ratio of stress a to strain e: TIME o = J-' (2) M = e Webb & Dingwell: Viscoelasticity 97 where J, the compliance is the ratio of strain to stress. The viscosity T] of a material is the ratio of stress to strain-rate T1 = j = (t»' 1 (3) where (j) is the fluidity of the material. In principle, the viscoelastic behavior of a melt can be determined as a function of time simply by applying a step function in stress and measuring the resultant deformation of the melt as a function of time. As shown in Figure 2, the modulus and viscosity determined depends upon the elapsed time after the application of the step function in stress that the deformation was measured. o n D _J D Q O >-H t/3 o u CO > to o UNRELATED ' RELAXED UNRELAXED I Nemonian viscosity RELAXED log 10 TIME Figure 2. Modelled time-dependent, relaxed and un-relaxed modulus and viscosity measured after the application of a step function in stress. For a melt of viscosity 10° Pa s and a modulus of 20 GPa, the application of 10 7 Pa stress results in an elastic deformation of 5 x 10 3 , total anelastic deformation of ~10 2 occurring within 5 s and a viscoelastic deformation of 1 occurring within 1000 s (17 min). For a melt of viscosity 10 2 Pa s the time required for similar amounts of anelastic and viscoelastic deformation is 5 nsec and 10 jisec, respectively. The need to measure 3 orders of magnitude in deformation over short periods of time makes it difficult to observe the viscoelastic behavior of melts in the time domain. It is, however, relatively simple to measure the large viscous deformation as a function of time and therefore to determine the shear viscosity of the melt from the time-dependent deformation in response to an applied stress (Dingwell, 1995; see also chapters by Dingwell; and by Richet and Bottinga).

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.