![]()

CHAPTER 1

SENIOR LIVING TODAY

STATE OF THE INDUSTRY

Since the first edition of Building Type Basics for Senior Living in 2004, the senior living industry has expanded and diversified in order to address demographic change. Recent U.S. census numbers reveal a variety of societal transformations. The industry has responded by shifting its focus from the World War II generation to the “silent generation” (some would argue they are not so silent) that matured and raised families in the burgeoning suburbs and witnessed the increase in product branding, the expansion of consumerism, and the invention of fast food. Baby boomers are altering the equation once again, as they seek options for their parents' care and envision themselves growing old. Products of postwar consumerism, they have expectations about services—and their quality and delivery—that do not mesh with the way healthcare and aging services have traditionally been provided.

The economic realignment that began in 2008 has also forced consumers (and sponsors) to reexamine available retirement options and plan for the kind of financial security they will need for services and settings as they approach 80 years of age. For the past decade, there has been a rise of community-based options with retirement living facilitated by technology. Remaining at home is not only a preference but for many is the only financially viable option. Choice, variety, and control are now embedded in the industry's lexicon; paging through retirement living sales brochures and websites affirms this evolution. No longer is it the facility or organization dictating products, services, and rules. Today, consumers are challenging that prescription, and facilities are responding to these new expectations.

Retirement living providers continue to expand wellness, dining, and recreation options in response to demands for more choices and a healthier lifestyle. Options that emerged at the beginning of the century continue to develop, with urban (sometimes high-rise), university- and college-affiliated, and co-housing solutions gaining traction in many markets. Traditional life-care models of retirement living are being challenged by more flexible entry criteria, and the transition to such communities is being handled in new and novel ways. Long-term care has evolved: a wide range of paradigms, including the “Green House” and “small house,” are replacing the traditional neighborhoods and households. The demand for sustainable and green design is growing to meet the new market's expectations of lower operating costs, healthy surroundings, and a concern for the environment.

Research metrics have also begun to shape the industry because quantifiable outcomes are expected. It is not enough to tell consumers their quality of life will improve. They want specifics: Will they fall less? Will their stress and blood pressure decrease? Will they have more friends and less depression? Government policies for reimbursing healthcare costs have set the stage for outcome-based measures, and these policies are trickling into long-term care. The Internet has made it possible to share consumer opinions—good and bad—of everything from washing machines to hotel rooms. Are senior living environments far behind?

Demographics

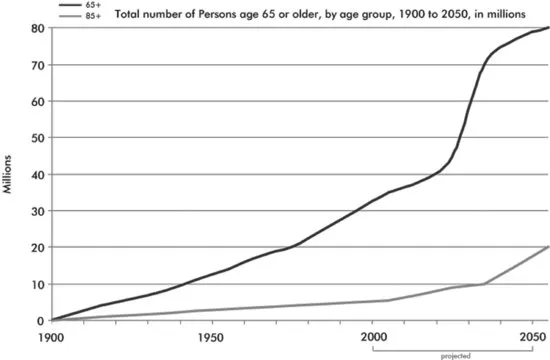

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, 13 percent of the population—over 40 million people—is 65 or older. That represents an increase of more than 5 million since the 2000 Census and makes this the fastest-growing age group: 15 percent per decade. Demographic projections for 2025 show the influence of the baby boom, with the population of those over 65 growing to over 63 million and that of those over 85 to over 8 million. By 2030, approximately 19 percent of the population in the United States, or 71 million people, will be over 65 (fig. 1-1). More people are living longer, and the growth of the over-100 age group is even more startling. The leading edge of the boomers, who are now 65, is almost 80 million strong.1 Meeting the housing and care needs of this rapidly growing segment of the population has become a major challenge for those setting public policy, sponsors, operators of facilities for aging adults—and those in the design professions.

These demographic trends are not unique to the United States. The world's population aged 65 and over is expected to increase from 6.9 to 16.4 percent, or approximately 1.53 billion people, by 2050.2 European countries are also dealing with a rapidly aging population and low birth rates. The rising cost of care, services, and housing for the aging has led to public policy changes in many countries. Asia is preparing for what many are referring to as the “aging tsunami.” In Japan, for example, there are already more people over the age of 60 than under the age of 29. By 2050, people 65 and over will have increased to 33–35 percent of the population3. China currently has approximately 169 million individuals over 60 years of age (12.5 percent), but by 2050 this number is expected to increase to 31 percent of the population.

In many countries, these demographic changes are coupled with transformations in the traditional multigenerational family. Older adults are living alone, using informal means of meeting their needs for services or relying on primary-care health services that offer inadequate support for their special requirements.

The United States is also facing the demographics of a more diverse population. Minority ethnic groups, particularly Hispanics and Asians, will present unique cultural requirements, and new affinity groups will appear as communities develop around religion, lifestyle, and even sexual orientation.

The huge baby boom generation, which transformed public and private institutions… is poised to change our communities once again.

American Society on Aging 2009

The increasing number of older people, combined with changes in the way they want to live out their later years and their expectations of a high-quality life, is creating the need for new care and housing options. New models of senior care and housing conceive of these environments not simply as healthcare facilities, but as seniors' homes. In addition, the search is on for new care models that support people at home longer and maintain them in the least restrictive (and least costly) conditions possible.

Accessibility

Such changes demand a flexible system that combines services with living arrangements. The aging in all countries have unique needs that must be recognized by those who provide them with care and housing. Most older adults will never occupy a residence designed specifically for older adults; most will stay at home and rely on family or community-based services. The built environment as a whole—including airports, shopping malls, and urban centers—must be planned and designed to respond to the large and growing segment of the population who will, over time, move a little more slowly, grasp a little less tightly, react a little less quickly, and process information differently. The environment has a greater impact on the quality of life of those who require a more supportive setting than it does on any other major demographic group. If properly designed, a senior living facility can contribute positively to an older person's independence, dignity, health, and enjoyment of life. If poorly planned and detailed, it can imprison, confuse, and depress.

In recent decades, the direct impact of design on the aging has been more widely recognized by both the general public and design professionals. Previously, the frail elderly who could no longer live in their own homes had few, if any, good alternatives. Most of the very old saw a shared room at an “old folks' home” as the only option. For the majority, it was a dreaded inevitability. Tens of thousands of families can tell stories of the trauma of having to place Mom or Dad in an institution. By 1980, there was a growing demand for more attractive options that would meet health- and support-service needs in a more agreeable residential setting. Lifestyle options for retirement have had to adapt to a changing clientele who are older, with more needs, but who expect higher-quality housing and activities than even a decade ago.

Solutions

Older adults are looking for more options. Today's 70-year-olds are better educated, generally have more money than their predecessors, and expect to be motivated physically and stimulated intellectually. The great recession of 2008–2010, and continued slow economic growth, will certainly change available financial resources for future seniors. Young boomers born in the late 1950s and early 1960s may have enough time to rebuild a portion of their financial portfolio, but their older siblings may need to delay retirement and alter their lifestyle expectations. Portions of the “silent generation” with higher-risk investments and facing declining real estate values have already decided to sit on the sidelines and look for less costly options. Affordability has always been a challenge for this industry, and it may be redefined to include a much broader swath of the older demographic who have assets that exceed the threshold for traditional subsidized housing but are insufficient for proper preventive healthcare and services.

This book provides an overview of the major issues involved in the planning, design, and development of specialized environments for this new group of aging Americans. Specifically, the book describes the issues associated with each of the 10 major building types within the general framework of design for aging. Chapter 2 has also been expanded to include specialized hospice programs and to review community-based options, some of which are driving new models of services and settings. The following are general definitions of these 10 types. Please see the following sections for more detailed descriptions, as well as the distinctions among the types.

1. Community-based options. Historically, the delivery of services to people in their homes through a visiting nurse or companion service. Beacon Hill Village—and the Villages Movement itself—has expanded this philosophy to one of keeping seniors in their neighborhoods by connecting them to service providers in the community.

2. Geriatric outpatient clinic. A specialized medical clinic that focuses on the physical, psychological, social, and medical needs related primarily to aging.

3. Adult day care/adult day health. A daily program that provides a blend of social and medical support during the day for those still residing in their own homes or with their families.

4. Nursing home/long-term care. A medically oriented residence for v...