![]()

1

An Introduction to Invasion Ecology

Overview

Public and academic recognition of the problems associated with biological invasions has grown exponentially over the past few decades. The reasons for this growth are threefold. First, the negative effects of some non-native species have grown too large to ignore. Second, over time the number of species transported into novel locations has grown, so that the overall number of identified problems has also grown. And lastly, with so many invasive species, it is very hard to do ecological field research without encountering non-native species and potentially including them in investigations even if those investigations are for basic research. Non-native species offer new interactions with the potential for new insights, and curious scientists rarely pass up the opportunity to explore such new avenues. Thus, increasing numbers of scientists are managing and studying non-native species to minimize the effects of biological invaders, to satisfy basic ecological curiosity, or both. In this introductory chapter we precisely define what we mean by a non-native species, settle on a general terminology for use throughout the book, and provide some exploration of what we mean by the “invasion process.”

What are invaders and why do we care about them?

One of the principal ways in which speciation occurs is through geographic isolation (i.e., vicariance speciation; Mayr 1963). Physical features such as oceans, mountains, ice sheets, and river valleys represent boundaries to the movement of individuals between populations of the same species. Over time these separated populations diverge via drift and selection, with each population eventually forming a unique species. This process generally happens on long, geological time scales. On those same time scales, we also see climatic and geological events that remove barriers and allow individuals to disperse over long distances and into previously unreachable areas. During these events, some species expand their ranges to intermingle with new communities and sample new habitats. For example, during the Miocene when the isthmus of Panama emerged from the sea to link North and South America, North American mammals moved south while birds and plants of the South American rainforests tended to move north (i.e., the Great American Interchange; Marshall et al. 1982). Such relatively rapid expansion of species groups is unusual enough to deserve special recognition, and paleontologists and ecologists have long been interested in why some species expand their ranges successfully in these events (while others do not) and have given these species a whole host of names (e.g., immigrants, waifs, colonizers; see Table 1.1).

As long as humans have had the ability to disperse across continents, they have also helped many other species breach geographic boundaries. Domesticated animals and plants have trailed along as human settlers have moved into novel territory (Crosby 1986). Almost certainly, representatives of non-domesticated species have hitched a ride in clothes, on boats or wagons, and within or on domesticated animals. Like the groups of mammals, birds, and plants that expanded their geographical ranges in the Great American Interchange, species moving with humans encountered locations that were previously out of their reach, and some of them successfully colonized these novel environments. These successful colonizers, however, achieved this new distribution with the help of humans. In the same way that ecologists distinguish between human-mediated and natural extinction of species, they also distinguish between natural and human-mediated rapid range expansion. This book concentrates exclusively on those species that found their way out of their native range and into a novel location via human actions.

There is ongoing discussion within the scientific community as to whether range expansions aided by humans are substantively different from range expansions that follow shifts in the earth’s paleoclimate (e.g., Vermeij 2005). We address this debate in Chapter 2. Suffice it to say here that, compared with natural range expansion, humans have massively increased the rate at which species colonize new areas, and they have substantially changed the geographic patterns of invasion. This is not to say that there is little to be learnt from examining invasion patterns in the paleontological record. It is never wise to ignore the lessons of history.

One of the reasons for the debate about natural and human-aided colonization and range expansion is to determine whether invasion, like extinction, deserves special attention or is a natural process. As with extinction, the answer is that the natural and human-aided processes share many characteristics. While examining the natural process may inform our understanding, there is no doubt that the human-aided process deserves and demands additional attention. There is ample evidence that non-native species can cause serious ecological and economic problems (Mooney et al. 2005). Invasive species eat, compete, and hybridize with native species often to the detriment of the natives. Invasion can result in the loss of native species and the loss of ecosystem services such as water filtration, soil stabilization, and “pest” control. More directly, most agricultural pests are non-natives, and many new human diseases are “emerging,” meaning they are non-native with us as novel hosts (Pimentel 1997). Invasive species clog waterways, impede navigation, destroy homes, and kill livestock and fisheries (Mooney et al. 2005). Whether or not we think modern invasions are historically unique, they demand our attention.

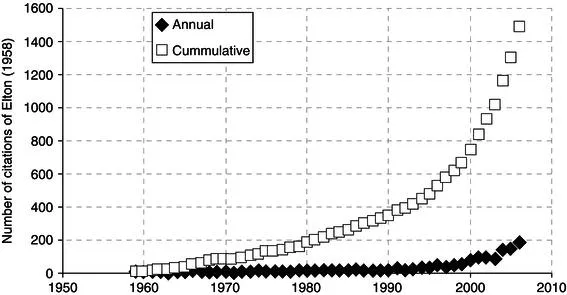

The motivation for this book comes as much from this practical concern as it does from the more esoteric interest in invasion as an ecological fact of life. This approach follows directly from the seminal work of Charles Elton (Box 1.1), who was one of the first to consider biological invaders as key drivers of ecosystem change and specifically of detrimental change (Davis 2006). The next seminal work on invasions, an edited volume by Baker and Stebbins (1965), took a more neutral stance. We (the authors) believe that biological invaders can act as useful “probes” into the inner workings of nature. Often we know the origins of non-native species, can document their arrival, and can directly collect information on their activities in their new community. This information allows the study of non-native species to become a powerful tool in our ecological and evolutionary arsenal (Sax et al. 2005; Cadotte et al. 2006a,b). Invasion ecology has swung back and forth through the years between an Eltonian view focused on invaders as problems and a less judgmental view, more oriented toward basic science. Interestingly though, the ascendency of the field has mirrored the rise in prominence of Elton’s classic book (Fig. 1.1) (Davis 2006; Richardson & Pyšek 2008). As ecologists, we (the authors) recognize the value of non-native species as unique sources of ecological and evolutionary knowledge and have conducted research from this point of view (e.g., Mathys & Lockwood 2011), but we also lean toward the Eltonian view that non-native species can drive change in ways that may be detrimental. Indeed the one thing that separates this text from a basic overview of ecology is its focus on how non-native species interact with human society, and how we can use ecological knowledge to thwart the influx and impacts of invasive species.

Box 1.1 Unknown legend

Charles Sutherland Elton (1900–1991) produced the foundational book on biological invasions, The Ecology of Invasion by Animals and Plants, in 1958, just less than 10 years before his retirement from Oxford University in 1967. This classic book grew out of a series of three radio lectures Elton made for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) under the title “Balance and Barrier.” Within the book, Elton summarized a relatively obscure literature on the impact and spread of non-native species that, at that time, was largely confined to the disciplines of entomology and plant pathology (Southwood & Clarke 1999). Perhaps because the original intent of the lectures was to reach a larger non-academic audience, The Ecology of Invasion by Animals and Plants is a pleasure to read. Elton manages the nearly impossible task of melding scientific rigor with an engaging and often witty writing style. As Dan Simberloff relates in his Foreword to the 2000 reprinted edition, “A writer who can describe oysters as ‘a kind of sessile sheep’ and characterize advances in quarantine methods by the proposition that ‘no one is likely to get into New Zealand again accompanied by a live red deer’ is more than just a scientist pointing out an unrecognized problem.” Because of his ability to communicate effectively in writing, Elton’s book has today become the most cited source in invasion biology (Richardson & Pyšek 2008).

The predominant feeling one gets after reading The Ecology of Invasion by Animals and Plants is that Elton presaged nearly all the arguments within the field, and indeed there are very few topics that we cover in this text that were not originally discussed by him. Due to the era in which he wrote, he could not have explored some currently hot topics (e.g., genetic diversity), was disinclined to pursue others (e.g., mathematics of population growth and range expansion), and given the rate at which global transportation has grown in 50 years, he could not have anticipated some emerging elements of the field (e.g., vector analysis; Richardson 2011). Nevertheless, one could argue that we are all simply putting mechanisms behind many of the patterns Elton noticed a half century ago. Of course, one could also make that argument for the majority of community and population ecology theories because Elton also wrote Animal Ecology (1927), Voles, Mice and Lemmings: Problems in Population Dynamics (1942), and The Pattern of Animal Communities (1966). Within these volumes Elton laid out the foundation for population cycles, food chains, pyramids of numbers, and the structure of communities. The first of these books was written in 85 days when Elton was in his late twenties (Southwood & Clarke 1999). If only we could all be so productive so early in our careers!

Presaging where ecologists stand today (especially as our work relates to biological invasions), Elton embraced the sociopolitical implications of his work and often steered his research agenda toward solving fundamental societal problems. He founded the Bureau of Animal Populations in Oxford during World War II in part to satisfy the need to reduce the loss of stored grains from over-abundant rodent populations (Southwood & Clarke 1999). He helped found The Nature Conservancy and sat on its Scientific Advisory Board until 1957 despite the fact that he was “allergic to committees” (Nicholson 1987 as quoted in Southwood & Clarke 1999). Elton made the critical connection between population cycles of mammals and human health concerns such as the plague, and, in an early example of cross-disciplinary collaboration, spent several years exploring the population cycles and parasites of voles and mice. Thus, perhaps his most lasting contribution was his recognition that ecology was a distinct discipline in biology, and that ecologists had a large role to play in how society dealt with the problems it faced. In this sense, and in several other ways, the book you are reading is clearly infused with the spirit of Charles Elton.

A brief history of invasion ecology

As Mark Davis points out in his work on the history of invasion ecology, the topic “would be a dream dissertation … for some history of science graduate student” (Davis 2006). The rapid rise of the discipline over the last decade continues a rather long history of scientific interest in non-native species that goes back at least to the publication of Elton’s book in 1958 (Richardson 2011). In addition, the list of scientists that have dabbled in invasion ecology over the decades reads like an all-star ecology roster, including such famous names as Ernst Mayr, E.O. Wilson, and Rachel Carson (Davis 2006).

Much like other modern disciplines, invasion ecology grew out of a variety of much older research foci including agriculture, forestry, entomology, zoology, botany, and pathology (Davis 2006). Within each of these disciplines there were scientists grappling with the effects of non-native species. Foresters were concerned about non-native species that decimated natural and managed forested lands. Agricultural scientists (e.g., plant pathologists) were concerned about non-native species that reduced crop yields. Animal scientists were concerned about non-native species that killed or caused disease in livestock and wild populations. Botanists were concerned about non-native species that transformed native plant communities. But some of the interest arose because scientists found the growing number of novel species in their location noteworthy and documented their presence and sometimes their interactions with native species. There was substantial and somewhat simultaneous work on non-native species occurring among European, North American, South African, and Australian biologists and natural resource managers throughout the 1950s and 1960s (Davis 2006). Because English has grown to be the language of science over the decades, much of the early work not published in English has unfortunately escaped notice by contemporary biologists (Davis 2006).

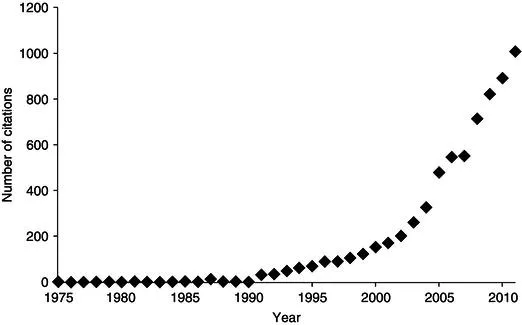

A rising interest in invasion ecology is manifest in the increasing number of contemporary publications related to invasive species. For a quick view of how interest in invasion ecology has changed through time we did a search in the Science Citation Index® for articles published between 1975 and 2011 that included as keywords “invas*” and “ecolog*” and the results are shown in Fig. 1.2. From 1975 to 1985 there were no articles that utilized variations of “invasion ecology” in their keywords. This almost certainly reflects the inconsistent use of the term “invasion” prior to the mid-1980s, but it also indicates a somewhat scattered and diffuse interest in the field during this time (Davis 2006; Richardson & Pyšek 2008). After 1990 there was an exponential growth in such articles. Indeed an exponential line fits the data depicted in Fig. 1.2 nearly perfectly (R2 = 0.9028).

There is a tiny blip in Fig. 1.2 around the mid-1980s that corresponds with the publication of the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) volumes. This committee, founded by the International Council for Science in 1969, is an amalgamation of environmental scientists that seeks to develop syntheses and reviews on various environmental issues. SCOPE pulled together a large group of ecologists from around the world between 1982 and 1989 to document the problems that invasive species posed (Mooney 2005). From the SCOPE focus, a series of books and journal articles on invasive species emerged, as well as a generation of newly minted PhDs wh...