eBook - ePub

Evil by Design

Interaction Design to Lead Us into Temptation

Chris Nodder

This is a test

Condividi libro

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Evil by Design

Interaction Design to Lead Us into Temptation

Chris Nodder

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

How to make customers feel good about doing what you want

Learn how companies make us feel good about doing what they want. Approaching persuasive design from the dark side, this book melds psychology, marketing, and design concepts to show why we're susceptible to certain persuasive techniques. Packed with examples from every nook and cranny of the web, it provides easily digestible and applicable patterns for putting these design techniques to work. Organized by the seven deadly sins, it includes:

- Pride — use social proof to position your product in line with your visitors' values

- Sloth — build a path of least resistance that leads users where you want them to go

- Gluttony — escalate customers' commitment and use loss aversion to keep them there

- Anger — understand the power of metaphysical arguments and anonymity

- Envy — create a culture of status around your product and feed aspirational desires

- Lust — turn desire into commitment by using emotion to defeat rational behavior

- Greed — keep customers engaged by reinforcing the behaviors you desire

Now you too can leverage human fallibility to create powerful persuasive interfaces that people will love to use — but will you use your new knowledge for good or evil? Learn more on the companion website, evilbydesign.info.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Evil by Design è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Evil by Design di Chris Nodder in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Design e UI/UX-Design. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Greed

The point is, you can't be too greedy.

Donald Trump

Greed is the desire to get or keep more stuff than you need, either accumulating money or possessions (“whoever has the most toys wins”) or just to feel better than someone else does.

Because greed prevents other people from having access to a thing that they could use more than the greedy individual could, it’s seen as selfish or spiteful. The reason it’s seen as one of the seven deadly sins is that greedy people obviously distrust that God will provide all they need.

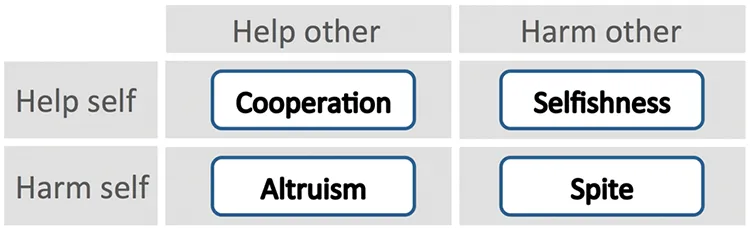

All talk of sin aside, there does seem to be a correlation between having more than one needs and being selfish. When talking about haves and have-nots, there are four possible behaviors: selfishness, altruism, spite, and cooperation.

Greed happens when people pursue their own agenda at the expense of others, leading to selfish or spiteful behavior. Paul Piff, a social psychologist at UC Berkeley, found that people who “had more” (those in higher social classes) were less ethical, and more likely to lie, cheat, or steal. Interestingly, it wasn’t that more greedy people made it to a higher social class, but that getting to a higher social class reinforced those behaviors, making people more likely to be greedy. As Piff puts it, “Upper-class individuals’ unethical tendencies are accounted for, in part, by their more favorable attitudes toward greed.”

The reverse is also true. In another set of studies, Piff found that people in lower social classes are more generous, charitable, trusting, and helpful even at cost to themselves. This helpful have-not behavior is classic altruism. Others in Piff’s team ran a study that found lower-class individuals were more compassionate and less selfish.

start figure The four possible behaviors between two people who want access to the same resources

It seems that the more you have, the less you need to rely on others. The less you need to rely on others, the less you care about them. The more you have, the more likely it is that you are surrounded by others who also have more, and so the less likely it is that you will need help. Greed therefore feeds upon itself, helping people to justify their increasingly selfish and spiteful behaviors.

So how does greed happen? How does it get reinforced? What triggers cause people to be greedy, and how do companies benefit from this behavior?

Learning from casinos: Luck, probability, and partial reinforcement schedules

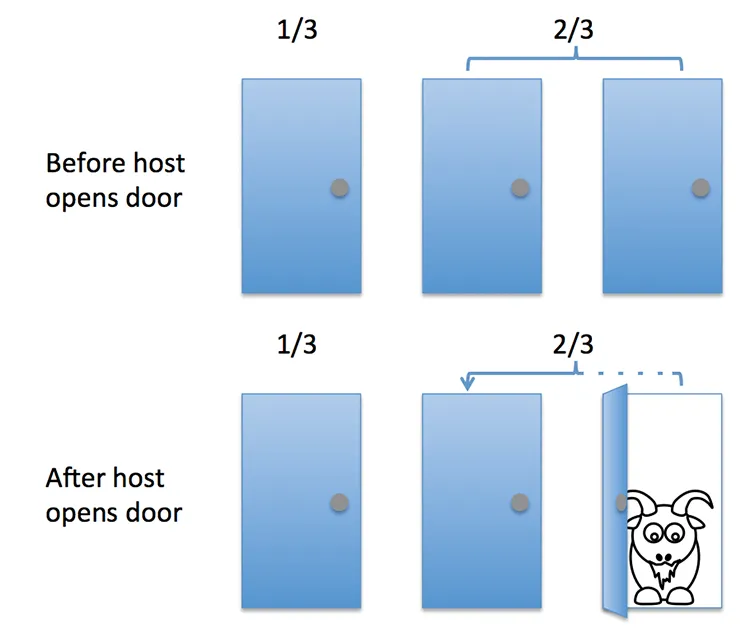

Imagine that you are a game show contestant about to make a play for the grand prize. You are shown three doors. The host tells you that a new car waits behind one door, and the other two doors hide goats. The host asks you to choose a door. After you choose it, the host opens one of the two doors that you didn’t choose, revealing a goat. Now, to add an element of excitement, the host gives you the option to switch your choice to the other unopened door. Assuming you’re more interested in winning a car than a goat, what do you do?

After the game show host opens the door, most people expect that there’s a 50-50 chance that they have already chosen the correct door. Because they have already made their choice, they are attached to their current door (the endowment effect) and so they stick with it.

However, the correct answer is to always switch because there is actually a two-in-three probability that the car is behind the other door.

Think of it this way: Before you made a choice, there was an equal one-in-three probability that the car was behind any door. That means there was always a two-in-three probability that the car was behind one of the two doors that you didn’t choose. That fact doesn’t change after you make your choice, and it doesn’t even change when the host opens one of the doors you didn’t choose. Even though you now know which door is not hiding the car, the other unchosen door retains its two-in-three probability because you could still theoretically choose the door that has already been opened.

start figure Say you first choose the left door. The probability of the car being behind one of the other doors is 2/3. It stays at 2/3 even after the host opens the right door. By switching, you keep the 2/3 probability with the added benefit of having one of the options eliminated.

If that explanation made your brain hurt, welcome to the world that most people inhabit. The previous example is called the Monty Hall problem after the host who popularized it on the Let’s Make a Deal game show, and yes, they really did use goats. It is a great demonstration of the difference between mathematical probability and common sense. And yet strangely, despite the confusion that most people feel when dealing with questions of probability, they feel qualified to play the odds every time they enter a casino or buy a lottery ticket.

In North America, lotteries created $66 billion in sales, resulting in a $20 billion profit in 2010. Forty-three states, DC, and Puerto Rico run lotteries, as does every Canadian province. Sixty percent of adults in states with lotteries report playing at least once per year.

Between them, casinos and lotteries account for 72 percent of all gambling in the United States. Americans spend more than $1 billion/day on slot machines in the 38 states where they’re legal.

On one level the people walking in to the casino to play the machines must know that their odds are low and that the house always wins. On another level, however, they are willing participants in the systematic removal of their money because they cling to a vague hope that they might just “win big.” Lotteries have the worst odds of all forms of gambling, but also the highest potential payout proportionate to investment. As the Kentucky state lottery slogan points out, “Somebody’s gotta win, might as well be you.”

The casinos’ and lottery providers’ job is just to reinforce this belief. How do they do this? As just pointed out, a large part of the problem is the players’ inability to properly measure risk.

We aren’t good at understanding randomness either. Consider the outcry when on July 11th 2007, the five numbers picked for North Carolina’s Cash-5 lottery were identical to the numbers picked on July 9th. There were cries of tampering and calls for investigations. The state lottery director even had to be dragged out to explain that different machines and different balls had been used on the two occasions, so it was impossible that tampering had caused the repeat. The thing is, although it looks strange, there’s no reason for the numbers not to repeat. That’s the nature of randomness. The same numbers are just as likely to come up again as are different ones. The probability of it happening in any given 3-day period is only 1 in 191,919.

And it has happened at least a couple of times subsequently. In September 2009, a Bulgarian lottery drew the same six numbers two times in the same week. In 2010, the Israel National Lottery produced the same numbers, pulled out in the exact reverse order, just seven draws apart.

Because it is hard to measure risk, and because we like to think we see patterns where there is only randomness, we’re susceptible to the gambler’s fallacy. That is, we believe that a win becomes more likely after a series of losses. And despite the cognitive dissonance you’d think it causes, we also believe that there is a “winning streak” effect, where after we’ve won once, we’re more likely to continue winning.

And that’s where the casinos draw us in. It’s okay to lose most of the time, just so long as we win occasionally, or at least are surrounded by people who appear to be winning.

start figure The appearance of winning—or nearly winning—is what makes casinos so appealing to many. (mandalaybay.com, excalibur.com, bellagio.com, luxor.com)

This occasional winning in among multiple losses is called a partial reinforcement schedule. To understand reinforcement schedules we should begin with Ivan Pavlov and his dogs. Pavlov was collecting dogs’ saliva to study their gastric function. He noticed that his dogs would start drooling more when they heard the sounds associated with food preparation. He experimented further, pairing the concept of food with the sound of a bell. When he subsequently rang the bell, the dogs would drool even though no food was present.

This was a continuous reinforcement schedule—every stimulus was associated with a reward. The dogs would stop responding (drooling) quickly if no food appeared after the bell was rung.

Later, B. F. Skinner was performing learning experiments with rats and pigeons when he found that sometimes withholding the reward for a correct behavior led to the animals continuing to exhibit the behavior for longer.

This became known as a partial reinforcement schedule. Unlike Pavlov’s dogs, who quickly stopped responding to the bell if no food was given to them, Skinner’s rats and pigeons would continue at the task for much longer if they were only rewarded (reinforced) occasionally rather than every time. For this reason, a partial reinforcement schedule is much harder to break than a continuous reinforcement schedule.

And what type of schedule do the casinos and lottery providers use? A partial reinforcement schedule. Humans respond in similar ways to rats and pigeons when given an occasional reward for repetitive behavior.

Casinos are a visual indication of the ways that companies can benefit from greed through creating aspirational, conditioned behavior and emphasizing the “luck” of winning. This section talks about several of the other ways that this is exploited.

start feature

Use a partial reinforcement schedule

You’ll keep people playing longer.

The principles used when training animals are not that different to those used when designing successful computer games. During an initial learning period, there must be a sufficient reward for the participant (animal or player) to continue exhibiting the correct behavior. Over time though, the rewards can be given further apart or only for certain combinations of behaviors.

When the rewards are backed off, they can either be given once every certain number of times the behavior is shown (a fixed ratio schedule), or on average once within a certain number of times the behavior is shown (a variable ratio schedule). Rewarding in a specific timeframe, again either fixed interval or variable interval, can do the same; although, this does not provid...