eBook - ePub

A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art

Babette Bohn, James M. Saslow, Dana Arnold

This is a test

Condividi libro

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art

Babette Bohn, James M. Saslow, Dana Arnold

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art provides a diverse, fresh collection of accessible, comprehensive essays addressing key issues for European art produced between 1300 and 1700, a period that might be termed the beginning of modern history.

- Presents a collection of original, in-depth essays from art experts that address various aspects of European visual arts produced from circa 1300 to 1700

- Divided into five broad conceptual headings: Social-Historical Factors in Artistic Production; Creative Process and Social Stature of the Artist; The Object: Art as Material Culture; The Message: Subjects and Meanings; and The Viewer, the Critic, and the Historian: Reception and Interpretation as Cultural Discourse

- Covers many topics not typically included in collections of this nature, such as Judaism and the arts, architectural treatises, the global Renaissance in arts, the new natural sciences and the arts, art and religion, and gender and sexuality

- Features essays on the arts of the domestic life, sexuality and gender, and the art and production of tapestries, conservation/technology, and the metaphor of theater

- Focuses on Western and Central Europe and that territory's interactions with neighboring civilizations and distant discoveries

- Includes illustrations as well as links to images not included in the book

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art di Babette Bohn, James M. Saslow, Dana Arnold in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Kunst e Kunstgeschichte der Renaissance. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Part 1

The Context

Social-Historical Factors in Artistic Production

1

A Taxonomy of Art Patronage in Renaissance Italy

On November 25, 1523, Michelangelo wrote from Florence to his stonecutter Topolino in Carrara with important news: “You will have heard that Medici has been made pope, because of which, it seems to me, everyone is rejoicing and I think that here, as for art, there will be much to be done.”1 Michelangelo spoke of Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici, who had been elected Pope Clement VII two days before. This passage reveals the necessarily symbiotic relationships of patrons and artists in early modern Italy. Each depended upon the other to secure their reputations by bringing works of art and architecture into existence. Although the strategies employed by artists and patrons were often mutually reinforcing, sometimes relations between them were adversarial.

Patrons in Renaissance Italy promoted personal, familial, and group renown by requesting works from – and fostering the careers of – famous or promising artists. Just as artists in this period often competed for the attention of patrons, patrons frequently competed for the services of successful artists. While artists of the caliber of Michelangelo, Raphael, or Titian often manipulated the patronage game to great advantage, most painters, sculptors, and architects in the period functioned within a deeply entrenched sociocultural system of mutual dependency. Even in the case of Michelangelo (who had, to paraphrase William Wallace, “reversed the rules of patronage”), in a painting for the Casa Buonarroti, his Seicento descendants had him depicted in the mode of a traditional presentation image, in which artist was subservient to patron (fig. 1.1).2

Taking as its starting point the patronage system that flourished in late medieval and Renaissance Italy, this essay provides an overview of various classes of patrons. Questions to be taken into consideration when examining art patronage include: Who were the men, women, and groups who commissioned works of art and architecture? What were their motivations for doing so? What were the social, political, and religious networks to which these patrons belonged? Why did they select certain artists and architects, and what were the mechanisms that led to commissions? What were the patrons’ economic circumstances, and how did class differences affect their commissions? It is important to stress that the patronage system was based on social stratification and inequalities in power and economic standing. Thus, in general, art patronage in this period was the province of elites, who had the means to extend commissions. Recent work has, however, demonstrated the existence of open markets for uncommissioned objects.3 In this essay, I will focus primarily on central and northern Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, with occasional discussion of earlier and later examples, and of cases elsewhere on the peninsula.

FIGURE 1.1 Jacopo Chimenti da Empoli, Michelangelo Presenting Pope Leo X the Project of the Façade of San Lorenzo, Casa Buonarroti, Florence, 1619. Photo: Scala / Art Resource, NY.

Patronage studies, which bring together issues of personal and group identity, political power, and cultural production, have come to occupy a significant place in the history of Renaissance art.4 We now understand much more about the processes of art patronage in this period and have come to ask new questions, in particular about the relationship between clientelismo (political and social patronage) and mecenatismo (cultural patronage); I concur with other scholars in seeing complex interactions between these two types of patronage.5 The latter term refers to Gaius Clinius Maecenas, advisor to Augustus and patron of Horace and Virgil. Other languages, such as French and German, also refer to patrons of the arts with terms alluding to Maecenas. The English term “patron” derives from the Latin patronus (protector of clients or dependents, specifically freedmen) which, in turn, derives from pater (father).

Borrowing approaches from several disciplines, including social history, anthropology, economics, and psychology, the study of patronage has come to emphasize kinship bonds, self-fashioning, the communication of social status, patronage networks, and the promotion of individual, family, and collective agendas.6 Artists and architects formed but one category in a patronage-based society; also vying for the support of the powerful were poets, musicians, historians, and other talented but dependent persons. Scholars have demonstrated the sometimes critical impact that individual, familial, and corporate (or group) patrons had on the form and content of art and architecture.7 In many cases, patrons took an active role in shaping the character of works they commissioned. On occasion, the underlying premises of patronage studies as an art-historical enterprise have been questioned, particularly when the scholarship is primarily biographical in character and fails to shed light on the works themselves.8 Such doubts notwithstanding, the principal textbooks used to teach Italian Renaissance art both stress the critical role played by patrons.9

A key concept for understanding patronage in early modern Italy is magnificenza, the classically inspired notion of magnificence that was increasingly put forth as a justification for patronage, particularly of architecture.10 In the mid-1450 s Timoteo Maffei, prior of the Badia of Fiesole, wrote a defense of Cosimo de’ Medici’s magnificenza, arguing that lavish patronage was an obligation of the wealthy.11 This would later become a trope of humanist discourse about patronage. At the end of the Quattrocento, the Neapolitan Giovanni Pontano wrote:

It is appropriate to join splendour (splendor) to magnificence (magnificentiae), because they both consist of great expense and have a common matter that is money. But magnificence (magnificentia) derives its name from the concept of grandeur and concerns building, spectacle and gifts.”12

For papal patrons, to be considered below, the related concept of maiestas papalis (papal majesty) was fundamental.

Historian Dale Kent has proposed that patrons, like artists, can and should be studied in terms of a complete body of work, an oeuvre, for which the patron can be seen, at least in part, as auctor (author).13 This concept, especially useful for patrons of multiple, large-scale commissions, implies self-consciousness on the part of men and women who wished to express their priorities and ambitions through visual means. Recently, Jonathan Nelson and Richard Zeckhauser have applied economic theories – particularly the economics of information and status signaling – to the study of art patronage.14

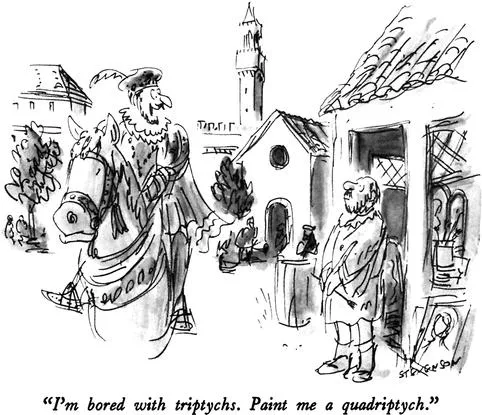

FIGURE 1.2 Cartoon, New Yorker Magazine, May 18, 1987. © James Stevenson / The New Yorker Collection / www.cartoonbank.com.

A New Yorker cartoon (fig. 1.2) of 1987 with the pithy caption “I’m bored with triptychs. Paint me a quadriptych” suggests near omnipotence for patrons (while perhaps unwittingly elucidating the role of patrons in the evolution of altarpieces). As I have pointed out elsewhere, however, the patronage process during this period was in reality a complex, dynamic, and flexible one in which realized commissions were the result of creative (and sometimes confrontational) interchange between patrons and artists.15 At the same time, as the longstanding biographical model for studying patrons has been problematized, the monolithic characterization of individual “hero-patrons” has been modified, as we understand more about collaboration among patrons.16

Rather than being a “two-way” street, the process of art patronage was, in fact, a complicated “multi-lane highway,” often involving intermediaries. Historian Melissa Bullard has illuminated the role of what she calls “shared agency” in Lorenzo the Magnificent de’ Medici’s political and cultural patronage, demonstrating how the importance of his secretaries and other agents – who took on considerable responsibility in carrying out his policies – has been lost in the celebration of the “great man.”17 Bullard’s approach suggests an important model for the study of art patronage.

The commissioning, display, and gifting of art remind us too of the critical importance of considering audience and response when examining patronage strategies. In her study of fifteenth-century Florentine patronage, Jill Burke emphasizes the importance of reception, situating family patronage within the context of collective societal bonds such as neighborhood and parish.18

The topic of patronage and gender has, in recent years, received overdue attention. In his Quattrocento architectural treatise, Filarete famously remarked that the patron was analogous to the father of a building, responsible for its conception, and that the architect was like the mother.19 Repeating an aphorism in his memoir, the Florentine banker Giovanni Rucellai (1403–81) similarly stated that men do two important things in life: procreation and building.20 These gendered understandings of patronage – and the male origins of the English term in the Latin pater noted above – correspond to patriarchal attitudes to gender and power in the Renaissance.

In the past twenty years, the patronage activities of women (sometimes called “matronage”) have become increasingly better known.21 Noteworthy women patrons include nuns like Giovanna da Piacenza, Correggio’s patron in Parma, and aristocratic women like Isabella d’Este in Mantua and Eleonora di Toledo in Florence, who employed, respectively, Andrea Mantegna and Agnolo Bronzino. Moreover, we now know that lesser-known, middle-class women also commissioned objects for the home and for ecclesiastic settings. Topics such as the patronage of gendered spaces, the roles of women in the purchase and display of objects, and conjugal competition are of particular interest. The significance of widows as patrons of art and architecture, particularly of funerary chapels and their altarpieces, has become clear in recent years. Another important theme is women’s patronage of female artists such as Lavinia Fontana.22

Traditionally, patronage studies have relied upon written documentation including inscriptions, contracts, inventories, wills, letters, poems, and biographies and memoirs of artists and patrons. In addition, non-verbal evidence such as stemmi (coats of arms), donor portraits such as the one seen in fig. 1.3, and imprese (personal devices) also provide information about the genesis of art and architecture. But the absence of documents is not always a dead end for understanding patronage.23

The following pages consider various classes of patrons active from the late thirteenth through late sixteenth centuries...