![]()

CHAPTER ONE

CURRICULUM: AN ACADEMIC PLAN

Ask any college student or graduate “What is the college curriculum?” and you will get a ready answer. Most think of the curriculum as a set of courses or experiences needed to complete a college degree. Some will refer to the total set of courses a college offers, others will mean the set of courses students take, and a few will include informal experiences that are not listed in the catalog of courses. Some may include teaching methods as part of their definitions, while others will not. At a superficial level the public assumes it knows what a college curriculum is, but complex understandings are rare. Even those closely involved with college curricula lack a consistent definition. A few may point out that we cannot define curriculum without reference to a specific institution because college and university missions, programs, and students vary widely in the United States.

Over the years, we have solicited definitions of curricula from faculty, administrators, graduate students, and observers of higher education. Most people include at least one and usually more of the following elements in their definitions:

• A college’s or program’s mission, purpose, or collective expression of what is important for students to learn

• A set of experiences that some authorities believe all students should have

• The set of courses offered to students

• The set of courses students actually elect from those available

• The content of a specific discipline

• The time and credit frame in which the college provides education. (Stark & Lowther, 1986)

In addition to the elements that provide the primary basis for an educator’s definition of curriculum, individuals often mention other elements, sometimes including their views of learners and learning or their personal philosophy of education. Faculty members with broad curriculum development responsibilities typically mention several elements in their definitions and may be more confident about which of those elements should be included or excluded.

These instructors seldom link the elements they mention into an integrated definition of the curriculum. They tend to think of separate educational tasks or processes, such as establishing the credit value of courses, selecting the specific disciplines to be taught or studied, teaching their subjects, specifying objectives for student achievement, and evaluating what students know. Probably the most common linkage faculty members address is the structural connection between the set of courses offered and the related time and credit framework. Colleges and universities in the United States have emphasized the credit hour since the early 20th century, having modified the Carnegie “unit” first introduced into secondary schools in 1908 (Hutcheson, 1997; Levine, 1978). Curriculum change efforts in the United States often focus on structure because numbers of credit hours and other structural dimensions of curricula are common to all fields. In fact, some observers believe that the most common form of curricular change is “tinkering” with the structure (Bergquist, Gould, & Greenberg, 1981; Toombs & Tierney, 1991), for example, changing course listings, college calendars, or the number of credits required for graduation. Although discussions of curricular reform seem to focus on these structural dimensions rather than on the overall experience envisioned for students, when legislators, policy makers, and the general public talk about “improving curriculum,” they have something more in mind than structural adjustments. To them, curricular changes should result in substantive improvements in student learning, and colleges and universities should be able to demonstrate such improvement. Today, demands for accountability and increased scrutiny of higher education call for greater consensus on what we mean when we say “curriculum.”

The Need for a Definitional Framework

Since the mid-1980s the extensive literature urging educational reform has focused on the ambiguous term “curriculum.” This word has been frequently modified by several equally ambiguous adjectives such as “coherent” and “rigorous” or linked with processes such as integration. Is it the set of courses offered that lacks coherence or integration? The choice of courses made by the students? The actual experiences students take away from the courses? The teaching styles and strategies chosen by the professors? Or all of these? To discuss curriculum reform meaningfully, we need a working definition of curriculum to guide discussion and help us determine what needs to be changed.

The lack of a definition does not prevent faculty members, curriculum committees, deans, academic vice presidents, instructional development specialists, institutional researchers, and teaching assistants from regularly making decisions about curricula. These individuals talk about “curriculum” with the untested assumption that they are speaking a shared language (Conrad & Pratt, 1986). This illusion of consensus becomes a problem when groups with different views come together to work for curricular improvement. In such circumstances, participants often argue from varied definitions and assumptions without spelling them out, particularly in working groups that include many disciplines. Such discussions can be frustrating and even grow contentious. For these and other reasons, curriculum development or revision is typically not a popular task among college faculty.

Many faculty and administrators will resonate with the definition of an undergraduate curriculum as the formal academic experience of a student pursuing a baccalaureate degree or less, particularly because this definition is broad enough to include learning experiences such as workshops, seminars, colloquia, internships, laboratories, and other learning experiences beyond what we typically call a “course” (Ratcliff, 1997). This definition may remind them that a curriculum, from the student perspective, is a very particular set of learning experiences. Yet, to provide a framework for productive discussions and wise decisions, faculty and administrators need a more precise understanding that can help them identify the specific aspects of curricula that must be addressed. Should we adjust the content of a curriculum or use different teaching methods to build student competencies? Should we consider new methods of delivery, such as distance or online learning, to reach different student populations? Should new assessment procedures be adopted to better measure student learning and thus inform curricular revisions?

Most definitions are too general to be very helpful to faculty and administrators faced with the task of curriculum development or revision because they do not identify the many decision points that, together, produce a specific curriculum. Overly general definitions hinder the ability to communicate the intentions of a curriculum to students, to evaluate it effectively, and to make the case for particular changes. Definitions, of course, are not prescriptions. Defining the term curriculum does not mean that everyone must agree on the content to be studied, how it should be studied, or who should study it. It does not mean that everyone must agree on the specific skills or outcomes students must achieve. Our higher education system is characterized—indeed distinguished—by diversity of programs and institutions that serve different students and different needs. A definition of curriculum that can be applied across these differences is required.

Defining Curriculum as an Academic Plan

To remedy the lack of a comprehensive definition of curriculum, we propose the concept of the “academic plan.” Plans, of course, can be variously successful once they leave the drawing board. Our goal in conceptualizing curriculum as an academic plan is to identify the critical decision points that, if effectively addressed, will enhance the academic experience of students.

A plan for any endeavor incorporates a total blueprint for action, including purposes, activities, and ways of measuring success. A plan implies both intentional and informed choices among alternatives to achieve its intentions; in this sense, it strives for the ideal. The intention of any academic plan is to foster students’ academic development, and a plan, therefore, should be designed with a given group of students and learning objectives in mind. This focus compels course and program planners to put students’ educational needs, rather than subject matter, first. The term “plan” communicates in familiar terms the kind of informal development process recognized by a broad range of faculty members across academic fields.

The academic plan definition implies a deliberate planning process that focuses attention on important educational considerations, which will vary by field of study, instructors, students, institutional goals, and so on. Despite such variations, the notion of a plan provides a heuristic that encourages a careful process of decision making. Every curriculum addresses each element of the plan described below—whether conscious attention has been given to it or not, whether a deliberate decision has been made, or whether some default has been accepted. Thinking of curriculum as a plan encourages consideration of all of the major elements, rather than attention to singular aspects such as specific content or particular instructional strategies.

In our view, an academic plan should involve decisions about (at least) the following elements:

1. PURPOSES: knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be learned

2. CONTENT: subject matter selected to convey specific knowledge, skills, and attitudes

3. SEQUENCE: an arrangement of the subject matter and experiences intended to lead to specific outcomes for learners

4. LEARNERS: how the plan will address a specific group of learners

5. INSTRUCTIONAL PROCESSES: the instructional activities by which learning may be achieved

6. INSTRUCTIONAL RESOURCES: the materials and settings to be used in the learning process

7. EVALUATION: the strategies used to determine whether decisions about the elements of the academic plan are optimal

8. ADJUSTMENT: enhancements to the plan based on experience and evaluation

This set of elements provides a definition that is applicable to all levels of curriculum. An academic plan can be constructed for a single lesson, for a single course, for aggregations of courses (for example, a program or major), for broader organizational groupings of majors (such as schools or colleges), and for a college or university as whole. Moreover, defining a curriculum as a plan allows plans at these several organizational levels to be examined for integrity and consistency.

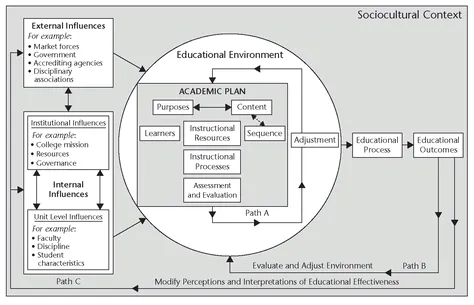

The model of the academic plan, however, includes more than the eight elements that define the plan itself. As we show in Figure 1.1, our complete model makes explicit the many factors that influence the development of academic plans in colleges and universities. In the first edition of this book (Stark & Lattuca, 1997), we divided these influences into three sets, building on work published by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (1977) and that of Joan Stark, Malcolm Lowther, Bonnie Hagerty, and Cynthia Orcyzk (1986). In this revised edition, we clarify the nature of these influences by further elaborating the role of social, cultural, and historical factors on curricula, faculty, and learners.

FIGURE 1.1. ACADEMIC PLANS IN SOCIOCULTURAL CONTEXT

Our slightly revised model of “academic plans in context” emphasizes the influence of sociocultural and historical factors by embedding the academic plan in this temporal context. Within the sociocultural context, we include two subsets of influences, divided into (a) influences external to the institution (such as employers and accreditation agencies) and (b) influences internal to the college, university, or educational provider. We further divide internal influences into institutional-level influences (for example, mission, resources, leadership, and governance) and unit-level influences (such as program goals, faculty beliefs, relationships with other programs, or student characteristics). These distinctions acknowledge the many levels (college, department, program, or course) at which academic plans are created and implemented.

Internal and external influences vary in salience and strength depending on the course, program, or institution under study. In Figure 1.1 we portray these specific influences as interacting to create an educational environment. We place educational processes and outcomes outside the educational environment for planning but within the larger sociocultural context. We recognize a multitude of influences that are beyond the control of planners, such as the attitudes and preparation of students who enroll in a course or program and the social and cultural phenomena that affect perceptions in a given time and place.

Figure 1.1 also shows the evaluation and adjustment processes both for a plan (Path A) and for the educational environment (Path B), which may itself be affected by the outcomes of academic plans. Finally, in Path C, we suggest that external and internal audiences can form perceptions and interpretations of the educational outcomes that may cause them to modify the kinds of influences they exert.

In the following sections, we elaborate on each of the main components of our model, discussing first the elements of the academic plan and next exploring the different influences on the plans, planners, and planning processes.

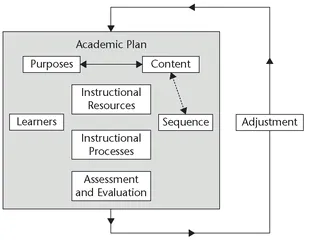

Elements of Academic Plans

Figure 1.2 isolates the elements of an academic plan. From interviews with faculty members we know that purposes and content are nearly always closely related elements of academic plans in the minds of instructors (Stark, Lowther, Bentley, Ryan, Martens, Genthon, & others, 1990). We illustrate this relationship with a double arrow in Figure 1.2. Frequently, instructors also link content with a particular sequence (or arrangement of content) as they plan. We show the relationship between content and sequence with a dotted double arrow to indicate that, while these elements are often linked by instructors, they are not consistently connected. We have arranged the other elements in their approximate order of consideration by college and university faculty members based on reports of how they plan (Stark & others, 1990). For example, faculty members tend to consider learners, resources, and sequence simultaneously, but after purposes and content.

FIGURE 1.2. ELEMENTS OF ACADEMIC PLANS

We have not inserted additional arrows into the academic plan model because we do not wish to imply that all curriculum planners do or should carry out their planning activities in a particular sequence. In fact, instructors reasonably make decisions in different orders and do so iteratively rather than in a linear fashion. This is especially true as they revise courses or programs based on their experiences in the classroom. In the following sections, we briefly describe each of the eight elements of an academic plan.

Purposes: Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes to Be Learned

Discussions about college curricula typically grow out of strong convictions. Thus, we have placed the intended outcomes, which we call purposes, as the first element in the academic plan. The selection of knowledge, skills, and attitudes to be acquired reflects the planners’ views—implicit or explicit—about the goals of postsecondary education. Research demonstrates that college faculty members in different fields hold varying beliefs about educational purposes (Braxton & Hargens, 1996; Smart, Feldman, & Ethington, 2000; Stark & others, 1988). Table 1.1 includes several broad statements describing some of these views. The second purpose listed in this table, “learning to think effectively,” is a commonly espoused purpose, but in any faculty group there are likely to be strong proponents of other statements as well. Some purposes will be strongly endorsed at one type of institution and minimized at another type. Considering a curriculum as an academic plan can direct attention to these differences in basic purposes and aid in the identification of underlying assumptions that can interfere with shared understandings of curricular goals.

TABLE 1.1. STATEMENTS OF EDUCATIONAL PURPOSE COMMON AMONG COLLEGE FACULTY

| A. | In general, the purpose of education is to make the world a bet... |