![]()

CHAPTER ONE

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE PHENOMENON

1.PREAMBLES

At the end of the Nineties the world of artistic-cultural production (from publishing, music, cinema, to multimedia) realized it had come to grips with the most innovative social and economic phenomenon since the period of industrial revolution: the coming of mass digital technologies and global communications networks.

Till that period the copyright model (born in England in the 18th century during the industrial revolution and became popular in the following two centuries in most industrialized countries) weathered all the previous waves of technological innovation; however the impact of this final phenomenon has been more destabilizing. People began to no longer consider creative works (which are the real object of copyright protection) as one whole object together with their physical support on which it was deliverable. A novel, to be read, did not need to be printed on paper as a book since it could be diffused in many ways and through various channels, thanks to digital and communications technologies; likewise a music track did not need to be printed on a vinyl disk or on an optical disk, nor did a film need a VHS cassette or DVD disk.

In the same period in parallel with the mass proliferation of digital and communications technologies, there was another cultural and social phenomenon, one of the most interesting in the last decades: we are referring to free and open source software (also known with the acronym FLOSS1) and the related coming of the copyleft model. It was in the information technology area (since the middle of the 80s) that the traditional copyright model, based on the “all rights reserved” concept, was really discussed. As a result an alternative copyright management model was found, implemented by enforcing innovative licenses.

This new model had already come to a certain level of maturity in the information technology area, and it had already seen some interesting experiments in other areas of creative production. In fact, between the end of the 90s and the beginning of the new millennium, many pilot projects were activated which proposed licenses that had been designed for text, music and in general artistic works. It was in this new wave of experimentation that the plan for the Creative Commons project was drafted: a project which from the start was shown to be something more structured and far-sighted in comparison with the projects which had previously appeared.

2.WHAT CREATIVE COMMONS IS

When we say in generic terms “Creative Commons”, at the same time we refer to a popular project and to the non-profit body which is behind it.

A. THE CREATIVE COMMONS PROJECT

The project, born from the initiative of legal and computer science scholars in Cambridge, Massachusetts, is actually very articulated; it is now present in over fifty countries around the world and supported by eminent intellectuals from different fields. Under its control there are other thematic sub-projects that are really important for their cultural far-sightedness.

The main objective of this project is therefore to promote a global debate on new paradigms of copyright management and to diffuse legal and technological tools (such as the licenses and all the services related), which can allow for a “some rights reserved” model in cultural products distribution.

B. THE CREATIVE COMMONS CORPORATION

In the beginning, the promoters and the supporters of the project organized a non-profit body with which to trace the dissemination activities connected to the project and thus to receive funding.

From a legal point of view the Creative Commons Corporation is a 501(c)(3) tax-exempt charitable corporation with its registered office in San Francisco. Presently it has no subsidiaries. Creative Commons forms agreements with pre-existing entities such as universities and research centers that are called “Affiliate Institutions” and which carry out local, national, and regional Creative Commons activities such as education, events, license porting, promoting adoption of Creative Commons tools, and translation.

C. THE PROJECT SPIRIT

At http://wiki.creativecommons.org/History there is a short introduction to the Creative Commons project and to its purposes: here below follows the complete text.

«Too often the debate over creative control tends to the extremes. At one pole is a vision of total control – a world in which every last use of a work is regulated and in which “all rights reserved” (and then some) is the norm. At the other end is a vision of anarchy – a world in which creators enjoy a wide range of freedom but are left vulnerable to exploitation. Balance, compromise, and moderation – once the driving forces of a copyright system that valued innovation and protection equally – have become endangered species.

Creative Commons is working to revive them. We use private rights to create public goods: creative works set free for certain uses. Like the free software and open-source movements, our ends are cooperative and community-minded, but our means are voluntary and libertarian. We work to offer creators a best-of-both-worlds way to protect their works while encouraging certain uses of them – to declare “some rights reserved.”»

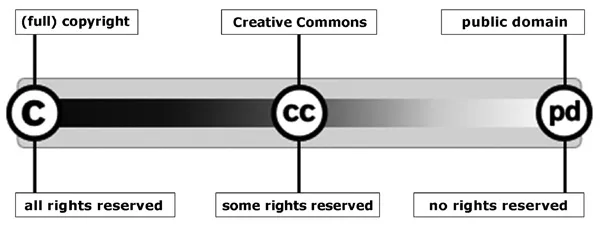

This mission is well described in a picture where Creative Commons symbolically represents a median shading between the “all rights reserved” model (characteristic of the classic copyright idea) and the “no rights reserved” (characteristic of a public domain idea or of a sort of no-copyright concept).

D. CURIOSITY: THE ORIGIN OF "CREATIVE COMMONS" NAME

Economist Garret Hardin published an interesting article in 1968 entitled “The tragedy of the commons”. In this article he displays his sharp interpretation of one of the most debated economic-social dilemmas.

In a nutshell, according to Hardin commons, i.e. those goods which are owned by nobody but which can be exploited by everybody, are always destined to a sad ending. He uses the metaphor of herders sharing a common parcel of land, «on which they are all entitled to let their cows graze. In Hardin’s view, it is in each herder’s interest to put as many cows as possible onto the land, even if the commons is damaged as a result. The herder receives all of the benefits from the additional cows, while the damage to the commons is shared by the entire group. If all herders make this individually rational decision, however, the commons is destroyed and all herders suffer»2.

Creative Commons theorists, and first of all Lawrence Lessig, argue instead that in the case of goods like creative and intellectual products, this problem does not exist because every creation increases its social value with the more people there are who can benefit from it. Furthermore, those goods are not liable to deterioration nor to a natural shortage because human creativity has no limits. Thus, we can validly talk about a “comedy of the commons”, where the goods at issue are precisely the creative commons.

3. WHAT CREATIVE COMMONS IS NOT

There are numerous misunderstandings created about the role and the function of Creative Commons. Therefore it is necessary to debunk at once the most diffused and dangerous ones.

A. IT IS NOT A PUBLIC BODY WITH INSTITUTIONAL DUTIES

Creative Commons Corporation as a civil law body, does not have any institutional role in any of the countries where the related project is active. This does not mean that some exponents of the cooperating community (and in any case also some members of the board) have not had the occasion to contact the public institutions of some countries in order to extensively inform about the new problematic areas of copyright theory. However, this is only in a perspective of cultural and scientific debate, not with a political overtone.

B. IT IS NOT A COPYRIGHT COLLECTING SOCIETY LIKE ASCAP, PRS OR SIMILAR

One of the most diffused and also misleading misunderstandings consists in mixing up Creative Commons with an alternative version of a copyright collecting society, which are present in every country and do not have the same exact function.

Quoting the Wikipedia definition, a copyright collecting society is «a body created by private agreements or by copyright law that collects royalty payments from various individuals and groups for copyright holders. They may have the authority to license works and collect royalties as part of a statutory scheme or by entering into an agreement with the copyright owner to represent the owners interests when dealing with licensees and potential licensees.»3

Creative Commons does not have a contractual relationship with copyright holders and does not hold a representation or enforcing role with regard to authors’ rights.

C. IT IS NOT A LEGAL ADVICE SERVICE

Neither the Creative Commons Corporation nor the communities and working groups connected to it provide legal advice or a legal aid service. Besides Creative Commons – as we wrote above – does not have any intermediation role; thus it cannot nor take the liability for the effects derived from the use of licenses.

To clear any kind of ambiguity, this is specified by an explicit preamble included at the beginning of every license4: «Creative Commons Corporation is not a law firm and does not provide legal services. Distribution of this license does not create an attorney-client relationship. Creative Commons provides this information on an “as-is” basis. Creative Commons makes no warranties regarding the information provided, and disclaims liability for damages resulting from its use.»

4. THE LOCAL PORTING OF THE LICENSES

As we partially discussed, the Creative Commons project is set out in:

- a central associational body, which is the official owner of the trademark rights, of the domain name “www.creativecommons.org” (and other connected domain names), and of the copyright on the official material published on the websites; and

- a network of Affiliate Institutions that act as points of reference for the several national Creative Commons projects scattered worldwide. This “hierarchical” composition (that from some people’s point of view can seem to be not very suitable to the spontaneous/collective nature of the opencontent culture) allows to check the correct porting of the licenses and to realize information and sensitization activities in an effective and coordinated way.

All the national Creative Commons projects are organized in two divisions: one dedicated to the legal aspects, such as the translation, the adaptation and explication of the licenses; and the other dedicated to the information-technology aspects, such as implementing technological solutions that exploit the Creative Commons resource. We can foresee a third division (crosswise two others) aimed at the sensitization and promotion of the Creative Commons philosophy; it organizes public events, manages mailing-lists and web-forums, creates informative material.

The idea of “license porting” involves a translation of the licenses into various languages, but also a concurring adaptation of the terms to the different legal systems. The other types of open content licenses, although they are diffused in different languages from the original, include a clause that, in the case of unclear interpretations, the involved operator (a judge, a lawyer...) has to refer to the text in the original language, which is the only one with an official character. Other types of licenses instead do not worry as much about the interpretation aspect as for the identification of the governing law, stating expressly that the “XY license” is regulated by the Japanese (or French, or Italian, etc.) law.

Creative Commons has tried to obviate both problems by implementing an important activity of “localization” of the licenses, that is devolved to the various Affiliate Institutions and monitored by the central body in the US. This way, the Italian, French and Japanese licenses are not mere translations of the American licenses, but basically independent licenses in accordance with the legal system of each country.

![]()

CHAPTER TWO

THE LICENSES

1.BASIC PRINCIPLES

First of all, to avoid falling into the most common misunderstandings about Creative Commons licenses, we should set the tenets that are valid for all the open content licenses.

A. DEFINITION OF “COPYRIGHT LICENSE”

A copyright license is a legal instrument with which the copyright holder rules the use and distribution of his work. Thus, it comes to a civil law tool which (based on copyright) helps to clear up for users what can or cannot be done with the work. The “license” term comes from the Latin verb “licere” and generically represents permission, in fact its main function is to authorize uses of the work.5

B.THE LICENSE AND THE RESTRICTION OF THE WORK

By clearing up the concept of license we can understand how one of the main misunderstandings about open content licenses is groundless: i.e. the one according to which a...