![]()

CONTENTS

List of Maps and Illustrations

Maps

Introduction

2. A passionate affair

3. The railways take hold

4. The battle lines

5. Harnessing the elephant

6. Railways to everywhere

7. Getting better all the time

8. The end of the affair

9. All kinds of train

10. The roots of decline

11. A narrow escape

12. Renaissance without passengers

Notes

Index

![]()

LIST OF MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

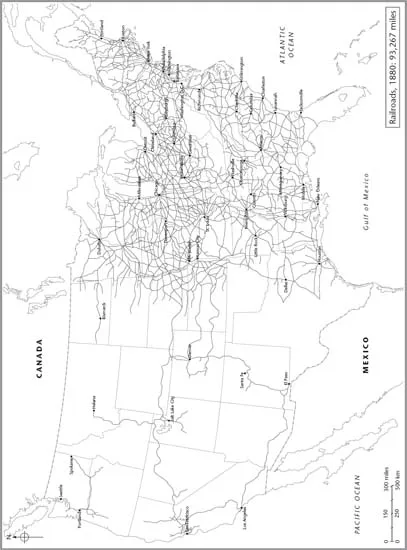

1. Railroads, 1880.

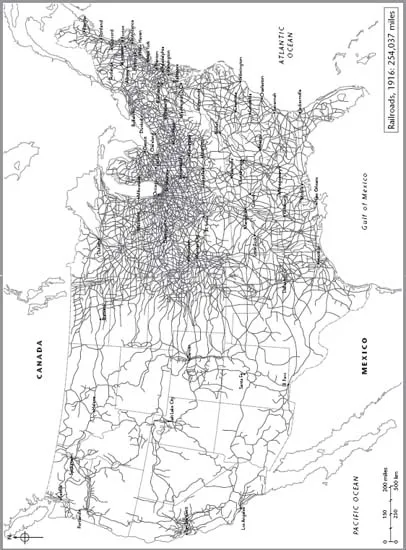

2. Railroads, 1916.

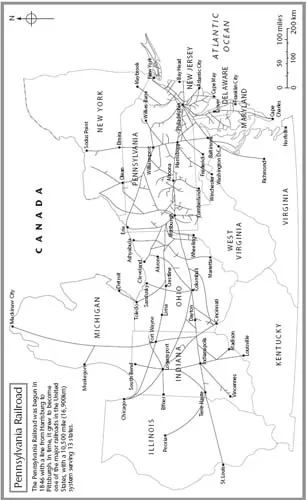

3. Pennsylvania Railroad.

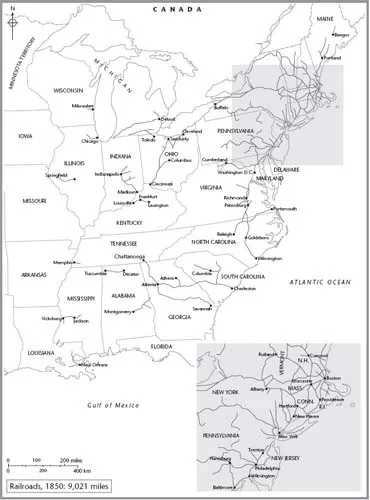

4. Railroads, 1850.

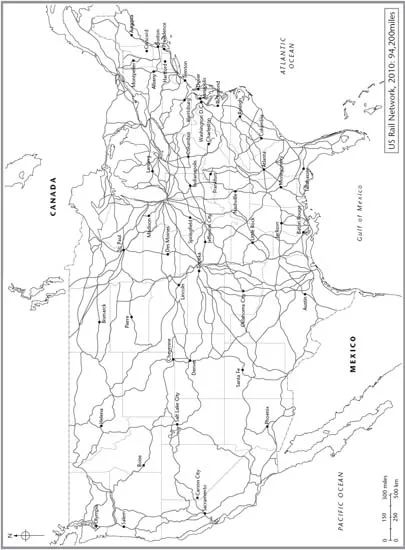

5. US Rail Network, 2010.

1. The Atlantic locomotive built by Phineas Davis. © Underwood & Underwood/Corbis.

2. The Best Friend of Charleston. Getty Images.

3. Completion of the first Transcontinental railroad. © Bettmann/Corbis.

4. Railroad travellers shooting buffalo. Getty Images.

5. The ticket office of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad. © Bettmann/Corbis.

6. ‘The Immigrants’ Guide to the Most Fertile Lands of Kansas’. © Bettmann/Corbis.

7. Farmers versus the railroads cartoon. © Corbis.

8. Completion of the Great Northern Railroad. © Minnesota Historical Society/Corbis.

9. Historical caricature of the Cherokee Nation © Corbis.

10. Texas Central Railway Yards in Houston. © Corbis.

11. Crowded passenger car illustration. ClassicStock/Alamy.

12. Railroad station in the Catskills. © Bettmann/Corbis.

13. Elevated railway section in New York. Getty Images.

14. B & O Railroad electric locomotive. © Schenectady Museum; Hall of Electrical History Foundation/Corbis.

15. Edward H. Harriman cartoon. © Corbis.

16. Dutch immigrants. © Minnesota Historical Society/Corbis.

17. A logging railroad in a forest. © PEMCO - Webster & Stevens Collection; Museum of History and Industry, Seattle/Corbis.

18. Cartoon on railroad influence. Getty Images.

19. Red Cross workers and World War I soldiers. © Minnesota Historical Society/Corbis.

20. Steam train on a trestle bridge. © Corbis.

21. Illinois State troopers at a railroad strike. © Bettmann/Corbis.

22. Pennsylvania Railroad Station. © Bettmann/Corbis.

23. Red Cap porter. © H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Corbis.

24. Three streamlined locomotives. © Bettmann/Corbis.

25. The Twin Cities Zephyr. © Underwood & Underwood/Corbis.

26. Pennsylvania Railroad poster. © Swim Ink 2, LLC/Corbis.

27. Southern Pacific poster. © Swim Ink 2, LLC/Corbis.

28. Passengers watching a movie on a train. © Bettmann/Corbis.

29. ‘Is Your Trip Necessary?’ poster. © Swim Ink 2, LLC/Corbis.

30. Senator Alben Barkley and President Truman. © Bettmann/Corbis.

31. Santa Fe Chief train wreck. © Bettmann/Corbis.

32. Amtrak’s Acela Express. © Ken Cedeno/Corbis.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

INTRODUCTION

America was made by the railways. They united the country and then stimulated the economic development that enabled the country to become the world’s richest nation. The railroads also transformed American society, changing it from a primarily agrarian economy to an industrial powerhouse in the space of a few decades of the nineteenth century. Quite simply, without the railways the United States would not have become the United States.

The extraordinary growth of the railways changed the very nature of America. From modest beginnings in the 1830s, the mileage grew to cover nearly 200,000 miles by the turn of the century, more than in any other country in the world. Yet, the epic tale of the growth of the railways and their influence on the development of the nation is now largely forgotten and ignored. By the middle of the twentieth century, as the automobile and the aeroplane continued their relentless march towards domination of the US domestic transport network, the historical importance of the railroads was being written out of the nation’s consciousness. Passenger railways were reduced to a loss-making rump. Mention the American railways to most people, and they will talk about them as a spent force. Yet railways still flourish in the United States, and are a vital part of the infrastructure. The tracks are still there but even when the huge freight trains run through town centres they somehow remain invisible to the American public. It is a surprising fact that America’s railroad network remains the world’s largest, and is the bedrock of the country’s freight transport system. There are, too, signs of a revival in passenger railways with money available from the federal government thanks to President Obama’s welcome, if flawed, stimulus package of 2009 and a rise in passenger numbers on Amtrak services. America may have gradually disowned its railroad heritage – but now is the time to reclaim and reinstate it.

This book attempts to do just that. While there are countless tomes on railway history, few have tried to tell the story of the railroads and their impact in one concise narrative. Obviously, that has meant taking a very selective approach and inevitably many facets of the rich story of the American railways have been left out. Inevitably, it has been impossible to be comprehensive and I have had to be selective on what aspects to cover in detail. I have, for example, chosen particular railways to look at in some depth as examples since there is no way that any book of a reasonable length could adequately cover the history of 250,000 miles of track which was America’s route mileage at the railways’ height. Obviously most of the prominent companies are mentioned in the book but there are numerous omissions for reasons of space or repetition.

As with several of my other books, I have focused more on the nineteenth century than the twentieth. That is deliberate. It was in the nineteenth that the railways were being built and they reached their zenith soon after the turn of the century. The story of the twentieth is one largely of decline and waning influence, a time when railways were losing their importance and where opportunities to make best use of this historic legacy were missed. While this period is covered in less detail than the early times, I try to explain why what started out as a love affair between the American people and their railways has turned out so badly and why an industry that makes such a positive contribution to America’s economy today is largely ignored or even reviled.

I have highlighted for particular attention the role of a few of the individuals who created or ran the railways, but again for reasons of space I have left out many other great characters who have contributed to the making of American railways during its near two centuries of existence. I make no apology, but hope the reader will understand how difficult this selection has been.

The first chapter looks at how railways emerged and why they developed as opposed to other forms of technology. Each aspect of what constituted a railway had to be conceived, developed and refined: track beds, rails, carriages and locomotives. Railways brought together the most complex set of technologies developed since the dawn of civilization. And America was a pioneer, joining the railway age just after the first modern railway had been opened in the United Kingdom. America was a young country, ripe for the railway revolution, and within a few years of the first line opening there were already a thousand miles in short separate lines laid principally on the Eastern seaboard.

Quite clearly, the railroad’s moment had arrived. It soon became obvious to its early promoters that – on grounds of efficiency and cheapness – locomotives rather than horses must be used to pull the carriages and railroad trucks. The first significant railway had been developed in Britain in 1830 and several European countries had quickly followed suit. The United States fast caught up and was soon leading the world in railway mileage. The railway age had arrived and nothing could stop it.

The second chapter shows how America’s relationship with the railroads soon became a passionate affair. They grew symbiotically, rapidly spreading across the more economically advanced states. From harbouring doubts about the railways, suddenly everyone wanted to be connected to the railway. The burgeoning United States adopted railroad technology faster and with more enthusiasm than any other nation, embracing the new invention which seemed to reflect the pioneering spirit of the age. Up and down the East Coast, railway lines sprang up with amazing speed, stimulating economic growth that would change the way people lived and eventually make America the most powerful nation on earth. Of the twenty-six states that comprised the Union in 1840, only four – Arkansas, Missouri, Tennessee and Vermont – had not completed their first mile of track. The beginnings of what would become the major railroad companies were established during the 1840s with the opening of the New York Central & Hudson River and Pennsylvania lines. However, for the most part in the 1830s and 1840s the development of the railways was a local affair. People wanted to have easy access to the local town, or possibly to the other end of the state, rather than across the nation. These early railway companies were a true ragbag of outfits, ranging from, literally, one-horse companies carrying coal out of a mine, to longer lines stretching into the outback and carrying thousands of passengers a week.

The third chapter shows how the railways took off as an industry in the years running up to the Civil War. The 1850s saw a massive increase in the pace of track development and the mileage more than tripled during the decade. This was a period of strong economic performance, both driven by the railroads and speeded up by their construction. Although most of the railroads were built by the private sector, little of this remarkable growth would have been possible without government support through various mechanisms, such as allowing companies to run lotteries, the granting of monopolistic rights, tax exemptions and land grants. It was the start of a difficult relationship between government and the railroads.

The American railroads were bigger in every sense than those in Europe. They covered longer distances, used larger locomotives and hauled longer trains. The railways seemed to be tailor-made for the huge American land mass and for the indomitable spirit of its people. European countries were constrained by reactionary governments slow to recognize the social and economic benefits of the railways and by old-fashioned customs that those with vested interests worked hard to protect. Americans, however – free from the shackles of tradition and unencumbered by obstructive government – took to the new method of transportation with far more gusto and enthusiasm than their European peers.

The Civil War, covered in Chapter 4, was the first true railway war and was particularly lengthy and bloody as a result. Key battles were fought around railroad junctions, railroad sabotage became a key tactic of the war, and troops were transported huge distances in a way that would have been impossible even a decade previously. The North, industrially stronger than its rival, was lent a key advantage by its superior railroads, which, crucially, were far better managed during the war than those of the South. The Unionists quickly realized that the operation of the railroads could not be left to chance and placed them under military control early in the conflict. By contrast, the Secessionists never established government rule over their railroads, with the result that they operated far less efficiently.

The war would also witness remarkable examples of derring-do on the railroads: the Andrews Raid (or Great Locomotive Chase) in April 1862 – in which Union volunteers commandeered a locomotive on the Western & Atlantic line, deep in Confederate territory, and created mayhem as they drove it north – has entered American folklore but somewhat obscured the true story of the railroads in this conflict.

The fifth chapter tells the story of the construction of the first Transcontinental railway in the United States. The idea of a coast-to-coast line had first been mooted as early as 1820 but it was not until the 1850s that the idea was seriously considered; its start was delayed by the Civil War, although ironically it was the absence of the Southern politicians which allowed the legislation to be passed by Congress. It was by far the most ambitious railway project of this period in the world – to be surpassed only by the Transsiberian, the subject of my next book – but its exact purpose was somewhat unclear. To reach the Pacific Ocean, 3,000 miles away, was an obvious ambition for the federal government in Washington seeking to unify the new nation, but it was never going to be a commercial proposition. Therefore financial and land grants were made available to the two companies building the line.

Thanks to lobbying by a remarkable young dreamer, Theodore Judah, who gained the political backing of Abraham Lincoln, Congress passed the Act to build the line in 1862. The law also allowed for massive subsidies in the form of both cash and land grants to the two c...