eBook - ePub

Holding aloft the Banner of Ethiopia

Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth Century America

Winston James

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 448 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Holding aloft the Banner of Ethiopia

Caribbean Radicalism in Early Twentieth Century America

Winston James

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Marcus Garvey, Claude McKay, Claudia Jones, C.L.R. James, Stokely Carmichael, Louis Farakhan-the roster of immigrants from the Caribbean who have made a profound impact on the development of radical politics in the United States is extensive. In this magisterial and lavishly illustrated work, Winston James focuses on the twentieth century's first waves of immigrants from the Caribbean and their contribution to political dissidence in America.This diligently researched, wide-ranging and sophisticated book will be welcomed by all those interested in the Caribbean and its migrs, the Afro-American current within America's radical tradition, and the history, politics, and culture of the African diaspora.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Holding aloft the Banner of Ethiopia è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Holding aloft the Banner of Ethiopia di Winston James in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Politica e relazioni internazionali e Politica globale. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

Politica e relazioni internazionaliCategoria

Politica globale1

Caribbean Migration: Scale, Determinants, and Destinations, 1880–1932

I see these islands and I feel to bawl,

“area of darkness” with V. S. Nightfall.

“area of darkness” with V. S. Nightfall.

Derek Walcott

Never seen

a man

travel more

seen more

lands

than this poor

path-

less harbour-

less spade.

Edward Kamau Brathwaite

It is little wonder that there was so much talk about Caribbean migrants in early-twentieth-century black America. For not only were they conspicuous in political agitation, they were also made conspicuous through distinctive cultural activities and sartorial taste. But most of all, these migrants were conspicuous, especially in New York City, through sheer weight of numbers. It was not that the Caribbean presence was new to America—far from it. Barbadian slaves had been taken by their British owners colonizing South Carolina during the seventeenth century, and earlier in the same century slaves from Barbados constituted an important portion of the black population of Virginia.1 South Carolina was in fact developed by and in subservience to Barbadian interests, supplying beef, pork, and lumber products to the island in exchange for sugar. And it has been persuasively argued that South Carolina was, even into the eighteenth century, the dependent of little Barbados—“an island master.” South Carolina, said Peter Wood, was the “colony of a colony.”2 Small wonder, then, that the settlement was referred to in London as “Carolina in ye West Indies,” for South Carolina was an integral member of the Caribbean universe of exchange and commerce. In the eighteenth century South Carolina extended and deepened its trading; relations with other Caribbean colonies, Jamaica surpassing Barbados as a market for its products. Up to 1700, it is safe to assume that all the slaves in South Carolina came from the Caribbean and Barbados in particular. It has been estimated that between 15 and 20 percent of slaves to South Carolina in the eighteenth century came from the Caribbean.3 But the degree of intercourse between the two areas, as Jack P. Greene has forcefully argued, was enormous.4 And the significant influence of the Caribbean on South Carolina endures to this day.

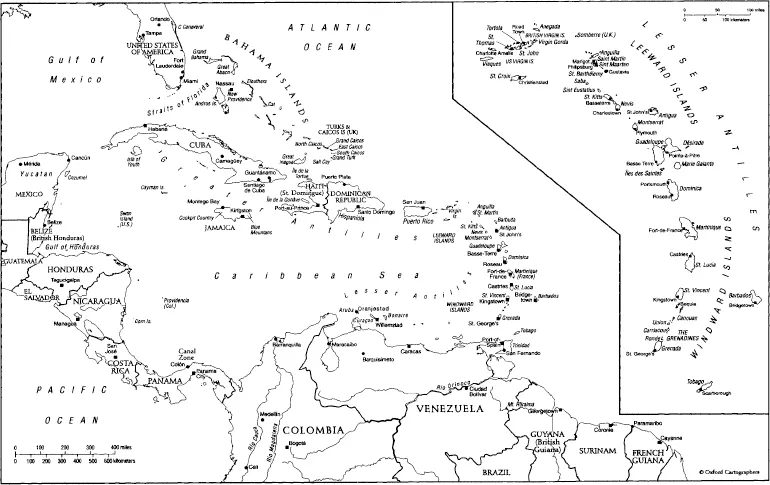

The Caribbean

But the pre-twentieth-century Caribbean presence in the United States extends well beyond colonial Virginia and South Carolina. Prince Hall, a Barbadian, established black freemasonry in the United States and was a distinguished leader of black Boston during the eighteenth century. Barbadians and other Caribbeans, apparently, constituted about 20 percent of the black population in Boston at the time.5 The Caribbean population in the United States was relatively small during the nineteenth century, but it grew significantly, especially after the Civil War. Indeed, the foreign-born black population, which was almost wholly Caribbean in origin, increased fivefold between 1850 and 1900, from 4,067 to 20,236, and distinguished Caribbean migrants populate the annals of nineteenth-century Afro-America.6

Denmark Vesey, who in 1822 in Charleston, South Carolina, organized a black uprising, was from the Virgin Islands. The conspiracy was betrayed and Vesey was executed. John B. Russwurm of Jamaica, one of the early New World settlers of Liberia, was one of the first three black people to graduate from an American college—Bowdoin College, Maine, in 1826.7 In the spring of 1827, Russwurm, with his Afro-American colleague, Samuel E. Cornish, started Freedom’s Journal, the first black newspaper published in the United States. Russwurm’s compatriot, Peter Ogden, organized in New York City the first Odd-Fellows Lodge among the black population. Robert Brown Elliott, the brilliant fighter and orator of the Reconstruction era, claimed Jamaican parentage.8 David Augustus Straker, a law partner of Elliott’s, a fighter for civil rights, educationalist, journalist, chronicler of the dark, post-Reconstruction days, and a distinguished lawyer in his own right, was from Barbados.9 Jan Earnst Matzeliger, the inventor of a revolutionary shoe-making machine, had migrated from Suriname. Edward Wilmot Blyden, a brilliant man and major contributor to the stream of black nationalist thought in America and abroad, was born in the Virgin Islands.10 William Henry Crogman, Latin and Greek scholar, a former president of Clark College and one of the founders of the American Negro Academy, came from St Maarten. Bert Williams, the famous comedian, was born in Antigua. And at the beginning of the new century Robert Charles O’Hara Benjamin (1855–1900), journalist, editor, lawyer, and writer, was gunned down—shot in the back six times—in Lexington, Kentucky, because of his work of “uplifting the race,” including writing and speaking out against lynching, and defending the constitutional right of black people to vote. On the morning of October 2, 1900, Benjamin had quarrelled with a white man, Michael Moynahan, over the latter’s harassment of black people registering to vote. Moynahan struck Benjamin several times with his revolver, for which Benjamin laid assault charges against him. Moynahan was arrested but released on bail within an hour. As Benjamin was returning home in the evening, Moynahan, armed with a rifle, ambushed him. Benjamin attempted to flee, but was cut down by Moynahan’s bullets. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, Moynahan was acquitted on grounds of self-defense. Even the white Kentucky newspapers—none of which was a friend of the Negro—thought the verdict an outrage. Benjamin had come from St Kitts and had lived and fought racism in the United States for almost thirty years before moving to Lexington in 1897.11 Although unfamilar and largely forgotten today, these people were widely known by Afro-Americans in the last century.12

A significant number of the nineteenth-century migrants were skilled craftsmen, students, teachers, preachers, lawyers, and doctors. Even more skewed in social origins than those who were to migrate to the United States in the twentieth century, these migrants gained a reputation that distorted Afro-America’s perception of the Caribbean reality. For, as Hubert Harrison observed, “It was taken for granted that every West Indian immigrant was a paragon of intelligence and a man of birth and breeding.”13

What was new in the early twentieth century was, therefore, not the Caribbean presence itself, but the scale of it. The number of black people, and especially Caribbeans, who migrated to the United States increased dramatically, from a trickle of 411 in 1899 to a flood of 12,243 per year by 1924, the high point of the early black migration (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2 and Figure 1.1, pages 355–7, 367 respectively). From a population of twenty thousand in 1900, the foreign-born black population in the United States had grown to almost a hundred thousand by 1930. Over a hundred and forty thousand black immigrants—exclusive of black visitors or tourists—passed through the ports of America between 1899 and 1937. And this occurred despite the viciously restrictive legislation of 1917 and 1924—the figure for those admitted in 1925 was 95 percent below that for the previous year—and the economic and migratory reversals of the Depression thirties. The overwhelming majority of these migrants came from the Caribbean islands, over 80 percent of them—if we include those of Caribbean origin coming from Central America—between 1899 and 1932 (see Table 1.2, pages 356–7). During the peak years of migration, 1913 to 1924, the majority headed not only for the state of New York, but also for New York City (see Table 1.3 and Figure 1.2, pages 358, 368). By 1930, almost a quarter of black Harlem was of Caribbean origin.

A series of interweaving developments, processes, and events triggered and sustained this massive exodus from the islands. And behind the surge of Caribbean migration in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries lay the long history of colonialism and the political economy of sugar.

By 1900 the islands had undergone four centuries of European colonial domination. This experience of prolonged colonialism has been the most important force in the Caribbean’s historical formation. And colonialism was accompanied for almost its entire duration by chattel slavery.

The European colonialists shaped the economies of the region to the benefit of the metropole and to the severe disadvantage of the overwhelming majority of the Caribbean people. The term “underdeveloped” (meaning relative retardation or economic regression) is often used to describe the economies of the Caribbean. This is overly generous and therefore is a misapplication of the concept, for the historical relationship between the Caribbean and Europe has, in essence, been a more brutal one than the term suggests. The Caribbean islands were annexed, their indigenous peoples (Arawaks and Caribs) subjugated and decimated. Having created a virtual tabula rasa of them, as it were, partly through genocide, the islands were then newly populated by the conquerors and by the forced migration of enslaved Africans.

Unlike Africa and Asia, and, indeed, much of continental (especially South) America, where the indigenous population form the base of the colonial edifice, in the Caribbean the native population was not only conquered but also—deliberately and partly inadvertently—destroyed. Upon the bones of the vanquished the Europeans created a new society fashioned essentially according to their colonial desires. The absence, at a remarkably early stage of colonialism, of an indigenous base is one of the most extraordinary, if not unique, features of Caribbean social formations. Caribbean societies, then, were literally new, not through the subordination and transformation of old forms but through the destruction of the latter and the creation of new ones.

Rather than having been a victim of “underdevelopment,” the Caribbean has quintessentially been a site of plunder and of the unrestrained fabrication of wealth uninhibited by the “inconvenience” of an indigenous presence. It is in more ways than one that the Caribbean has been a construction of Europe—albeit a perennially contested one.

John Stuart Mill’s interesting observation in the nineteenth century that Britain and its Caribbean possessions had a relationship of town and country has the merit of drawing attention to the organic nature of the economic relationship between the center and the periphery—what some would later call the relationship of metropolis and satellite, imperial center and colony. “If Manchester,” observed Mill,

instead of being where it is, were on a rock in the North Sea … it would still be a town of England, not a country trading with England: it would be merely, as now, the place where England finds it convenient to carry on her cotton manufactures. The West Indies, in like manner, are the place where England finds it convenient to carry on the production of sugar, coffee, and a few other tropical commodities. All the capital employed is English capital; almost all the industry is carried on for English uses; there is little production of anything except the staple commodities, and these are sent to England, not to be exchanged for things exported to the colony and consumed by its inhabitants, but to be sold in England for the benefit of the proprietors there.14

But this formulation—leaving aside the counterfactual and therefore problematic nature of the argument—also over-simplifies the relationship, for the Caribbean colonies were never simply the country to Britain’s town. As colonies, they were organic to Britain, but they were also foreign, overseas; here as part of Empire, but always there, in “the West Indies.” As a part of Empire, they were defined as British and thus central, but by the very same token—as colonies—they were, by definition, marginal, paradigmatically Other. This was the fundamental and inherent tension of the Imperial Idea. Despite the ideological smokescreens, however, it was always very clear that not only politically but also economically the colony was subordinate and subordinated to the imperial heartland—the colony belonged to the “Mother Country.”15

At the beginning of the century, the world was undergoing momentous transformations and the Caribbean was in the throes of extraordinarily rapid and profound changes. By 1890, Africa—from the Mediterranean to the Cape—was writhing in agony as the imperial powers of Europe hacked away at the continent, like butchers with cleavers, to take possession of their self-allocated segments. At the Berlin Congress of 1884–85, they had decided how they would distribute the spoils of their handiwork of coordinated and pre-meditated plunder. No longer confined to the coast, imperial Europe was busy penetrating Africa’s vast hinterland, joining its conquests from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean.

Africa, however, was not the only victim of the times. In Asia and Latin America an increasingly vigorous penetration of capital, characteristically accompanied by the displacement of peasants from the land, was underway. An increase in the level of poverty and a widening of economic inequality attended the process. By the beginning of our century, the Philippines, Guam, Cuba, and Puerto Rico had fallen under the overt tutelage of the United States of America. Emerging by this time to be by far the most powerful industrial nation in the world, the United States had transformed the Caribbean sea into a de facto American lake.16

But the changes in the archipelago were complex and profoundly uneven. There was, on the one hand, the tumult of the sugar revolution in the Hispanic Caribbean, especially in Cuba, and the relatively profitable adjustments of the planter class in Guyana and Trinidad to economic competition on the world sugar market. In marked contrast to these economies, the older British colonies such as Barbados, St Kitts, and Jamaica entered the doldrums as far as the sugar industry was concerned. Indeed, it was a period of catastrophic decline and painful reorganization of the sugar industry in the British Caribbean as a whole. Thus, while the British Caribbean produced in the 1820s just under 56 percent of the total average annual output of 331,000 tons of Caribbean sugar, in the first decade of the twentiet...