![]()

1

Speaking Stones: Inscriptions of Identity from Civil War Monuments

My first impression of the English Civil War was from my childhood atlas. The map of England was divided into red and blue zones – a device with which we have become all too familiar from the visual representation of our own contemporary political divisions (illus. 2). The historical baseline for my map was provided as being 1643, a year after the war had started. But the two coloured zones were peppered with notifications of the main battles that would follow, culminating in the Battle of Worcester in 1651. Place names, even when lacking identification by the tiny crossed swords denoting a battle, were also included because of their close association with some crucial episode or other in this countrywide confrontation, such as Maidstone, the scene of the battle that conclusively suppressed the so-called Kentish insurrection of 1648. This event will be at the centre of my study of one family, and one county’s experience, in the chapter that follows.

In this opening chapter I will be ranging far and wide. My first question, however, is posed from the vantage point of the present day. What do we now see to remind us of the events of the Civil War in the cities and towns that witnessed the conflict? The signs are usually there, but as they have to compete with contemporary signage, they need to be sought out. They often appear vague and elliptical. Information distributed in the parish church of Newbury states that prisoners from the losing side were held there after the Battle of Newbury. But there were two battles in the vicinity of this strategically placed market town, as my map had reliably indicated. There were also, in the full course of the war, two King Charleses to be taken into account, though the pub bearing that name in a nearby street in Newbury does not specify which of the Stuarts is being referenced. The city of Gloucester, by contrast, has erected informative new signage throughout the centre. The history of this important crossing point of the River Severn has been brought into view again in the smart plaque that adorns the New Crown Inn. We are informed there that a young Parliamentary commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Massie, adopted this inn as his headquarters in his successful defence of the city against Charles I’s much larger army in 1643, and so ‘changed the course of the war’. This concern to revive the memory of the conflict was evidently also a feature of Gloucester’s earlier civic awareness. There is an elaborate overmantel carved by the local artist George Armstrong Howitt, which was originally in the Guildhall and now resides in the city’s museum. The lively busts of Cromwell and Charles I confront one another from the two sides of the now inoperative fireplace.

The reason for marking the spot where a significant event took place during the war can often spring from a rather oblique kind of association. There is a plaque at the top end of Park Street in Bristol that records the cavalry charge which achieved the so-called ‘Washington’s Breach’. This was, in fact, the prelude to the Royalist army’s temporary occupation of this major city and port. But the credit line on the inscription makes it apparent that the plaque owes its existence to the fact that the particular Washington in question happened to be a collateral ancestor of the first president of the United States. Happily, the joint initiative of the local Improvement Society and the University of Bristol has resulted in the placement not far away of another, rather more informative plaque. Situated beside the only surviving bastion of the ‘Royal Fort’, which Prince Rupert reconstructed after capturing the city in 1643, it puts on record his final surrender to the forces of Sir Thomas Fairfax and his Lieutenant General of Horse, Oliver Cromwell, on 11 September 1645. Once more, with perhaps more justification than in Gloucester, we are to take note of ‘a turning point of the Civil War’.

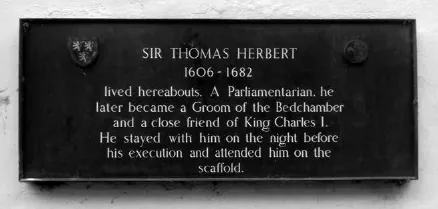

3 Plaque in memory of Sir Thomas Herbert in High Petergate, York.

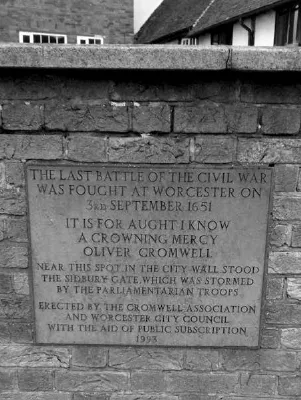

4 Plaque on a Worcester bridge commemorating the Battle of Worcester (1651).

On occasion, a plaque will call attention not to a decisive military exploit, but to the existence of lesser-known actors in the civil conflict. Near to the Bootham Gate in York is an inscription that announces: ‘Sir Thomas Herbert 1606–1682 lived hereabouts.’ In case this name leaves us somewhat mystified, it then catches the imagination with an intriguing scrap of biography: ‘A Parliamentarian, he later became a Groom of the Bedchamber and a close friend of King Charles I. He stayed with him on the night before his execution and attended him on the scaffold’ (illus. 3). While it does take the controversial figure of Herbert at his own valuation, this notice also brings to mind the historiographical aspect in the transmission of Civil War memories. By the early nineteenth century, Herbert’s published testimony was frequently quoted in historical accounts of the last weeks leading up to the king’s execution. He is represented in person as the thoughtful witness who surveys the scene in Delaroche’s painting of Charles I Insulted by the Soldiers of Cromwell (1837), which will be the subject of a later chapter.

For the most part, these contemporary plaques that are to be seen throughout the country defer to local sentiment without adopting a strongly adversarial point of view. The closest to outright celebration, in this very limited survey, would be the inscription on the bridge at Worcester that commemorates Cromwell’s crushing victory over the future Charles II at the Battle of Worcester in 1651 (illus. 4). This gains its emotional effect through quoting, and capitalizing, the Lord Protector’s famous exclamation: ‘IT IS FOR AUGHT I KNOW A CROWNING MERCY.’ Erected as late as 1993, and jointly subsidized by the Cromwell Association, Worcester City Council and a public subscription, this obviously justifies its prominence in the city that provided the focus for a unique Civil War narrative: not just the victory of Cromwell over the Stuart heir to the throne with his predominantly Scottish army, but the picaresque episode of the escape of the future Charles II. As I shall show in a later chapter, the first and foremost feature of the Civil War to be pictured and described, apart from the execution of Charles I, was the tale of the younger Charles, who was still a boy at its inception: of his hiding in the Boscobel oak and sundry other adventures that culminated in his eventual flight to France. Worcester displays the whole spectrum of this history in an enterprising museum that bears the traditional name of ‘The Commandery’. This was in origin the location where the Royalist troops set up their headquarters before the Battle of Worcester, and where the Royalist commander, the Duke of Hamilton, was brought back to die after the battle. Worcester also advertises the building from which the younger Charles was believed to have made his fortunate escape, and in this case the portrait hanging outside the seventeenth-century café leaves no doubt as to which Charles’s image is before us.

5 The King Charles Tower, Chester, with royal arms and inscription on a stone plaque, surmounted by a stone carving of a phoenix rising from the flames.

All of these public notifications operate, in a simple way, as historical ‘shifters’ that punctuate the network of contemporary signs in the city. But they cannot be said to give much of a stimulus to the historical imagination. The one further case that I will offer in this category attempts rather more ambitiously to induce a more direct form of historical experience, but in its claim to personalize a particular viewpoint it surely exposes the paradox of any such exclusively visual resurrection of the past. The Roman walls of the city of Chester were restored and strengthened by Lord Grosvenor in the late eighteenth century, and one of the principal towers came to be known as the King Charles Tower (illus. 5). The edifice in question blends seamlessly with its picturesque setting, surrounded by green foliage, the city walls having now become (as in many historic cities) both a proud badge of antiquity and an area in which tourists may stroll, having left their cars in the adjacent car park. Yet the inscribed stone that has been inserted at the entrance to this particular tower invites us to participate in imagining a more remote prospect: ‘King Charles stood in this tower and saw his army defeated at the Battle of Rowton Moor.’

6 William Dobson, The Prince of Wales, 1642/3, oil on canvas. The future King Charles II is portrayed after the Battle of Edgehill, at the commencement of the Civil War.

So what might it mean to imagine what King Charles would have seen? Or to put it in a different way, what would it mean to see the battle, so to speak, through Charles’s eyes? We cannot escape being familiar with contemporary photographs of the recreation of Civil War battles by enthusiastic volunteers such as the members of the ‘Sealed Knot’. These images find their way into the collage of pictures and headlines that meets us in our morning newspaper. But it would be odd to claim that something akin to these strenuous performances by well-drilled amateurs would be what Charles I might have observed of the Battle at Rowton Moor, even with the support of an exceptionally powerful telescope.

I make this obvious point in order to indicate that this chapter will not be concerned with visualizing the past in any such literal sense. It will, all the same, be about the part that visual data play in framing and enhancing the messages of memorial inscriptions that date from the period around the Civil War. This enquiry is, of course, quite different from the cursory study of contemporary signage that I have attempted so far. It has been rightly argued that the aesthetic choices regarding such inscriptions were ‘neither arbitrary nor decorative, but are usually indicative of the overall message of the monument’.1 I would add the additional point that the monuments of this period open up a seam of historical experience in so far as they are particularly well qualified to embody and illustrate the process of mourning. Precisely because they bear the signs of unwonted delay and intentional vandalism, they communicate in eloquent terms the ethos and the pathos of the Civil War period.

There is good reason, from my point of view, to select examples such as these in preference to the canonical paintings and sculptures that survive from the period. A chapter was closed in the early 1640s. Anthony Van Dyck died in 1641, and Cornelius Johnson – a portraitist of such an ubiquitous practice that I cannot resist referring to the perilous state of one of his works in my second chapter – returned in 1643 to the Holland of his ancestors. Van Dyck’s successor as court painter, from 1642 onwards, was the outstanding native artist William Dobson, aptly assessed by John Aubrey as ‘the most excellent painter England hath yet bred’.2 Dobson’s robust self-portrait from the late 1630s, painted when he was in his mid-twenties and currently on loan to Tate Britain, certainly supports this evaluation. Dobson followed the king when he set up his court in Oxford in 1642. Two of his noteworthy portraits from the succeeding period attest to his skill in emblematizing the conflicts of the early Civil War period. His portrait of the youthful Prince of Wales, the future Charles II (Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh), includes a head of Medusa that lurks in its lower corner, and competes for attention with the level gaze of the heir apparent (illus. 6). According to Aubrey, it was intended to commemorate his participation in the Battle of Edgehill, but somewhat idealized his actual role in the conflict.3 The splendid portrait that represents an attendant at the Oxford court, the wealthy patron of the arts Endymion Porter (Tate Britain), achieves an uneasy balance through associating the attributes of classical culture with those of the game hunter. Porter holds a gun, and his dead quarry is being proffered to him by a page. Lines from the poet Edmund Waller (to whose contemporary verse I shall return several times) support the view that the motif of the gun is hinting at the barbarity of war in the present age. Commenting on his friend Christopher Wase’s translation of a Latin treatise on hunting, Grati Falisci, Waller observes:

. . . the face of warre

In ancient times does differ far

From what our fiery battels are.

Nor is it like (since powder knowne)

That man so cruel to his owne

Should spare the race of Beasts alone.

No quarter now, but with the Gun

Men wait in trees from Sun to Sun

And all is in a moment done.4

Even more striking than these individual portraits, and arguably in a class of its own as a coded representation of the strains of the...