![]()

PART I

Where Do We Stand on the Bureaucratic Path Towards Safety?

![]()

Chapter 1

The Never-Ending Story of Proceduralization in Aviation

Claire Pélegrin

Introduction: Procedures in Aviation and Their Evolution

Aviation is very often cited as a model by other industries for its capability to manage risk, safety and human performance. Procedures and check-lists are not new and not specific to aviation: in the railways industry, the first check-list was implemented by Western Union for train drivers in 1852 in the United States (Gras 1998).

The objectives of this chapter are not at all a criticism of the aviation system, but rather a description of how far proceduralization has gone. The objective is to highlight the corresponding evolution of the underlying philosophies (including their justifications) and also to question the limits of this approach.

It is often said that learning from experience is of paramount importance in aviation, but there is a huge gap between the philosophical aspects and the practices; because serious incidents and accidents are extremely rare, learning from them is not so simple. Setting general recommendations from single events is really difficult due to specific context of each event and to the difficulty to generalize from specific situations, crews, circumstances, and so on.

A shared philosophy and its associated principles is that having safety guidance and learning from return of experience will ensure safety. Aviation learned that human performance is a key element. Hence the idea came to integrate human factors and the multiple aspects of safety in aviation. This was supposed to be done in different domains and at different levels of the aviation system (including regulatory bodies). This was done using what was available: procedures. But the constraints of real life and all elements of skills, dynamics of the situation, context, multitasking render things even more difficult.

Incidentally, we can mention that in aviation, although working together every day, pilots and controllers do not share the same philosophies and practices regarding procedures.

Air Traffic Controllers have few procedures and check-lists. Their philosophy is that a controller is trained and educated to work in a specific centre within a specific team. This is achieved through training and tutoring by peers.

Pilots are not at all in the same environment. They are trained and educated to be able to work with anyone else thanks to their standard environment. Their entire career is organized in a highly prescribed world, with procedures, checklists, do-lists. Procedures are inherent to flying activities.

Proceduralization at the Operators Level

Procedure and individual expertise, the military heritage

At the beginning of aviation, the designer, the engineer and the pilot were … the same person, thus there was no real need for procedures. When pilots took notes, it was just for them as a tool to remember flying techniques or personal tips (what to do, how to repair, how to adjust a part, and so on).

Aviation has gone a long way with proceduralization and for many years, aircraft have had check-lists and procedures. Procedures were generalized during the Second World War when there was a need to train, quickly and efficiently, a large number of military pilots. At that time procedures and check-lists were built for single-pilot operations and were considered as a tool to describe, step-by-step, what pilots were supposed to do. The underlying reason was to provide a memory tool (what to do and what to check) in response to insufficient training time due to the need to have many pilots ready in a very short period of time.

At the beginning of commercial aviation, aircraft design focus was on reliability of systems; then it was extended to include human reliability aspects. At that time, most efforts were on pilot selection and training: thanks to ‘superman qualities’, selected and well-trained pilots were supposed to manage almost any situation in flight. Commercial aviation, using military pilots, had continued and transmitted these values (‘superman’ pilots like astronauts).

For years, everybody shared the same idea that safety would be guaranteed if pilots were selected and trained to strictly apply procedures.

The method was: ‘tell them, train them, have them follow procedures … and safety will be guaranteed’.

In addition, the promotion of international aviation pushed for more standardization including phraseology to allow communication anywhere around the globe: it represents a new step through a proceduralization of communication. There is a strong hypothesis that the system guarantees the level of safety thanks to pilots’ qualifications, training and skills: ‘anywhere, anyone can fly, navigate and communicate with anyone’. The purpose of introducing procedures was to enhance safety in normal and abnormal conditions by reducing uncertainty and therefore risks. The rationale was obvious, and the benefits so blatant that the aeronautical industry has been using procedures for many years. It is now undisputed that pilots shall adhere to the procedures designed for them. So, procedures are not seen as a constraint. Young pilots usually praised the added value of procedures.

It is interesting to note that, in the former Eastern Bloc countries, with Russian aircraft, pilots did not use too many written procedures in the aircraft: a good pilot was a pilot who knew everything by heart. This was explained by several interviews with East European pilots (who were surprised by the number of written procedures on Western aircraft). This is another expression (a mental one!) of proceduralization: even if there are no paper or electronic procedures, the pilots have them all in mind.

As opposed to many industries (like manufacturing where prescription exists for low-level tasks) we can find in aviation highly qualified operators with high levels of expertise and procedures that are not seen as a contradiction (Dubar 2000). Imposing standards questions the problem of individual variability and the level of expertise of the operator. The level of expertise of the operator is specified and therefore the hypothesis made on his/her skills. Prerequisites, qualifications, minimum experience are specified. And at the same time we always refer to ‘basic airmanship’ (even if no one has the same definition of airmanship). Procedures are written rules and as such respected by the pilot population because they have been validated by other pilots; there is more proximity than in other industries where procedures are elaborated by people outside the operational group. It is what pilots or other professional groups call their autonomy margin. There is, most of the time, a space for dialogue between those who write the rules and those who have to apply them. The fragile frontier between an appropriate adaptation of a rule and a violation still causes a lot of ink to flow.

How teamwork and crew performance have been proceduralized

At the beginning of the 80s, several major accidents demonstrated that good pilots and good procedures were not sufficient to guarantee safety. Furthermore, these accidents happened with no failure, well-trained and recognized pilots who failed to work as a team.

It was the beginning of Crew Resource Management courses which were later developed in the US and then worldwide. These training courses used knowledge acquired from psychology and sociology, and transformed it to match cockpit crew environment (working in a complex, dynamic and critical environment).

Aviation has also gone a long way with proceduralization of ‘soft science and soft skills’ like Human Factors and Crew Resource Management (CRM). In the mid 90s, the CRM became mandatory in the frame of several regulations. This means that the content of the training, even the way to address some sections of the course, was specified and proceduralized. The communication and coordination in the cockpit were, at the same time, enriched with explanations of these HF skills but also became more rigid. In addition, the non-technical skills assessment inflight is now part of the pilot’s evaluation.

We see that procedures evolved from memory tools to support tools to get better situation awareness and organize the task sharing.

Then cockpit tasks have been organized through check-lists, do-lists and procedures. The philosophy behind is very stringent, dictating the accurate way of configuring, flying the aircraft and communicating.

In a flight manual which is a regulatory document attached to the aircraft, we can find normal, abnormal and emergency procedures. This means that they are really part of the ‘how to use and operate the aircraft’ concept.

Procedures and check-lists are designed to be used by any pilot, including non-English native speakers. It should be noted that English is everywhere: it is used for procedures, for standard phraseology between pilots and air traffic controllers. English is the ‘procedural language’ and it is also the training vector and contributes to this proceduralization. The ‘call outs’ – useful for teamwork and crew coordination – are announced in English because they are based on aircraft system statuses which are written in English.

Within an airline, procedures are aimed at everybody with (even if this assumptions is not always clearly expressed) the same level of qualification, knowledge and skills. But this model may evolve, especially nowadays, with the change of licences and qualification requirements.

Everybody knows the obvious role of procedures as a guide for action (individual and collective guide). It gives guidelines to pilots about:

• what to do

• when to do it (sequence, synchronization)

• how to do it

• who should do it (organized task sharing)

• what to observe and what to check

• what type of feed-back is provided to the other crewmember.

But procedures also have additional safety functions, which are part of the implicit values shared within pilots’ community. They support:

• Situation awareness and anticipation: CRM training emphasized that they support a shared action plan and shared awareness which is essential because it creates a mental image to act, synchronize action and manage time. Crew coordination based around the idea that collective reading will raise the level of awareness of both pilots.

• Decision-making by providing elements of diagnosis to prepare the action, element of control (cautions, what to do under different conditions and what to check). In case of failure, a modern aircraft will automatically trigger the appropriate status page and the associated do-list.

• Error management by preventing the likeliness of errors. They are a common reference, which allow the detection of errors. Built around an organized task sharing, the procedures allow each crewmember to stand back from the actions performed by the other one, which gives a kind of ‘fresh eye’ on the tasks performed by the other crewmember.

• Risk management in a complex and dynamic situation.

Crew resource management training promotes the idea that standardization and procedures plays an important role in safety. In addition, standard phraseology is also built to ensure effective communication. Even briefings are standardized: they help organize the task and set action plan, which is adapted to unexpected events.

The role of procedures has continued to evolve from a need for task-sharing purpose and workload management issue to a need to manage crew performance (collective aspects and crew coordination).

Normal check-lists (which represent a complete sequence) help manage the transition between flight phases: they allow for checking if the aircraft configuration is appropriate and safe for the next flight phase (these checks are structured and organized through a defined visual scan). They are organized through defined roles and task sharing in the cockpit: Pilot Flying (PF) and Pilot Not Flying (PNF).

The PF is responsible for flying (thrust levers, flight path control, airspeed, aircraft configuration), navigating and communicating; the PNF is responsible for monitoring the systems, reading aloud the check-lists and performing actions requested by the PF.

Check-lists are initiated by the Pilot Flying – PF. The PNF reads the check-list and the responses are given by the PF. At the end the PNF announces ‘check-list completed’.

The proper task sharing is defined and included in the procedure. Few procedures are applied without referring to paper (or electronic) check-lists: thus they should be known by heart.

Some do-list items help guide the action: PF calls for an item; PNF sets the item to the correct position and then announces the status of the item (‘gear down’). Once the item is accomplished, they proceed the same way to the end of the do-list.

Some other do-lists help understanding the situation in order to choose the appropriate action step-by-step: ‘leak from engine confirmed …’/‘leak from engine not confirmed …’.

The abnormal and emergency check-lists are rarely performed by flight crews in daily operations; pilots are aware of their criticality and they know that the misuse of such check-lists could be tricky for their own safety.

Having observed many flights, it is interesting to note that flight crew activity and the way the flight is organized with procedures and check-lists throughout flight phases may give the impression of a ‘show’ with some rituals (check-lists) that organize the collective work in the cockpit. Even if each flight is different, these rituals are strong and give a pace to the flight: the way to announce a call-out or an item of the procedure gives an idea of their importance.

Standard Operating Procedures are the skeleton for a collective work where each pilot does not know the experience and the skills of the other. This enables the task to be visible and more transparent: everybody knows exactly what the other is doing and can anticipate what will happen next.

Procedures evolve from a guide and support to act as a shared tool, a shared reference which will help to detect deviations and errors. In this way procedures play an important role in teamwork. The written standard being more predictable, the ambiguity and uncertainty of human behaviour are therefore reduced.

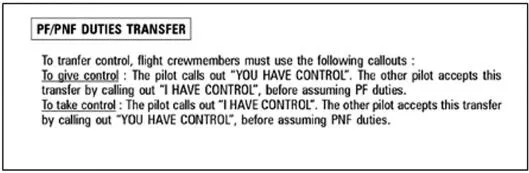

The transfer of tasks between crewmembers is specified.

Procedures also play an important role in interpersonal relationships and in conflict management because they are seen as a neutral reference: in case of disagreement, following the procedures is one way to solve conflict. This is taught in many CRM courses.

Figure 1.1 Example of procedure for duties transfer

Limits of this proceduralization

Although procedures are part of pilot life, everything is not predictable, and there is no magic in procedures. Mismatches do exist...