eBook - ePub

Virtual Reality Filmmaking

Techniques & Best Practices for VR Filmmakers

Celine Tricart

This is a test

- 180 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Virtual Reality Filmmaking

Techniques & Best Practices for VR Filmmakers

Celine Tricart

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

Virtual Reality Filmmaking presents a comprehensive guide to the use of virtual reality in filmmaking, including narrative, documentary, live event production, and more. Written by Celine Tricart, a filmmaker and an expert in new technologies, the book provides a hands-on guide to creative filmmaking in this exciting new medium, and includes coverage on how to make a film in VR from start to finish. Topics covered include:

-

- The history of VR;

-

- VR cameras;

-

- Game engines and interactive VR;

-

- The foundations of VR storytelling;

-

- Techniques for shooting in live action VR;

-

- VR postproduction and visual effects;

-

- VR distribution;

- Interviews with experts in the field including the Emmy-winning studios Felix & Paul and Oculus Story Studio, Wevr, Viacom, Fox Sports, Sundance's New Frontier, and more.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Virtual Reality Filmmaking è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Virtual Reality Filmmaking di Celine Tricart in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Medien & darstellende Kunst e Film & Video. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Part I

Theoretical and Technical Foundations

Chapter 1

History of VR

Eric Kurland is an award-winning independent filmmaker, past president of the LA 3-D Club, Director of the LA 3-D Movie Festival, and CEO of 3-D SPACE: The Center for Stereoscopic Photography, Art, Cinema, and Education. He has worked as 3D director on several music videos for the band OK Go, including the Grammy Award-nominated “All Is Not Lost.” He was the lead stereographer on the Academy Award-nominated 20th Century Fox theatrical short “Maggie Simpson in ‘The Longest Daycare’,” and served as the production lead on “The Simpsons VR” for Google Spotlight Stories. In 2014, he founded the non-profit organization 3-D SPACE, which will operate a 3D museum and educational center in Los Angeles.

Figure 1.1 Hugo Gernsback

While virtual reality is a relatively new innovation, the state of the art is greatly informed by the many forms of immersive media that have come before. For practically all of recorded history, humans have been trying to visually represent the world as we experience it. Primitive cave paintings, Egyptian hieroglyphs, and Renaissance frescos were early attempts to tell stories through images, and while these would not be considered true representations of reality, they do illustrate the historical desire to create visual and sensory experiences.

Third Dimension

Virtual reality as we know it today has some of its earliest roots in the 19th century. In 1838 scientist and inventor Sir Charles Wheatstone theorized that we perceive the world in depth because we have two eyes, set slightly apart and seeing from two different points of view. He surmised that the parallax difference between what our eyes see is interpreted into depth, and proved this by designing a device to allow the viewing of two images drawn from different perspectives, one for each eye. His device, which he called the stereoscope (from the Greek meaning “to see solid”) proved his theory to be correct. Wheatstone’s stereoscope, a cumbersome device using mirrors to combine the two views, was the first mechanical means of viewing a reproduced three-dimensional image. With the invention of photography in the decade that followed, we finally had a method of capturing multiple still images from real life and creating stereograms: immersive images for stereoscopic viewing.

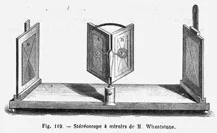

Figure 1.2 Wheatstone’s stereoscope

Another scientist, Sir David Brewster, refined the design of the stereoscope into a handheld device. Brewster’s “lenticular stereoscope” placed optical lenses onto a small box to allow the viewing of pairs of backlit glass photographic slides and front-lit photo prints. His viewer was introduced to the public at the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, England, where it became very popular, helped greatly by an endorsement by Queen Victoria herself. An industry quickly developed to produce stereoscopes and 3D photographic images for viewing.

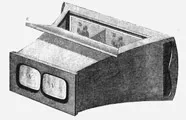

Figure 1.3 Brewster’s stereoscope

In the United States, author and physician Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. saw a need to produce a simpler, less expensive stereoscope for the masses. In 1861 he designed a stereoscope that could be manufactured easily, and specifically chose not to file a patent in order to encourage their mass production and use.

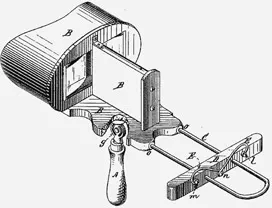

Figure 1.4 Holmes’ stereoscope

Throughout the latter half of the 19th century and until the 1920s, stereoscopes became a ubiquitous form of home entertainment. Companies such as the London Stereoscopic Company, the Keystone View Company, and Underwood & Underwood sent photographers around the globe to capture stereoscopic images, and millions of images were produced and sold. Stereo cards depicted all manner of subjects, from travel to exotic locations, to chronicles of news and current events, to entertaining comedy and dramatic narratives. Stereo viewers were also used in education, finding their way into the classroom to supplement lessons on geography, history, and science. Much of the appeal of these stereoscopic photographs was the ability of a 3D image to immerse the viewer and virtually transport them to faraway places that they would never be able to visit in person.

Figure 1.5 Stereoscopes in use in a classroom, 1908

Immersive Presentations

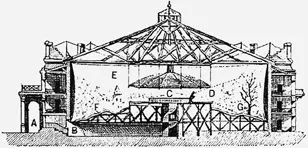

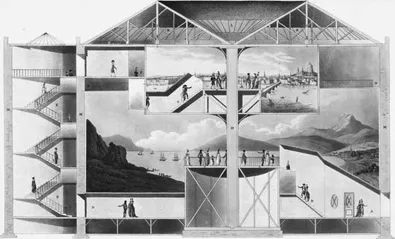

Another popular form of immersive entertainment in the 18th and 19th centuries was the panorama. The term panorama, from the Greek meaning “to see all,” was first used by artist Robert Barker in the 1790s to describe his patented large-scale cylindrical paintings which were viewed from within and surrounded the viewer. Barker constructed a rotunda building in London in 1793 specifically for the exhibition of his panoramic paintings. The popularity of Barker’s panorama led to competition and many others being constructed throughout the 1800s. Historically, a panorama (sometimes referred to as a cyclorama) consisted of a large 360° painting, often including a three-dimensional faux terrain and foreground sculptural elements to enhance the illusion of depth and simulated reality, and building architecture designed to surround the spectator in the virtual environment.

Figure 1.6 A panorama

Figure 1.7 Illustrated London News. “Grand Panorama of the Great Exhibition of All Nations,” 1851

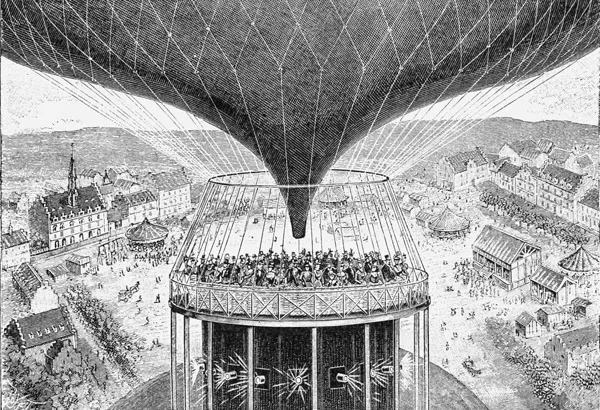

Figure 1.8 Cinéorama, invented by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson for the Paris Exposition of 1900

The grand panoramas of the period created the illusion for the audience of standing in the middle of a landscape and scene, while the depicted events were happening. These paintings in the round served both to entertain and to educate, often depicting grandiose locations or great historical events. Panoramas proved to be very successful venues, with over 100 documented locations in Europe and North America. Some notable installations include the Gettysburg and Atlanta Cycloramas, painted in 1883 and 1885, which depicted scenes from those American Civil War battles, and the Racławice Panorama in Poland, a massive painting 49 feet high and 374 feet long, painted by artists Jan Styka, Wojciech Kossakover, and a team of assistants over the course of nine months from 1893 to 1894 to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Polish Battle of Racławice. During their heyday in the Victorian period, the panoramas saw hundreds of thousands of guests each year.

The post-Industrial Revolution brought about a new age of technological advances. The birth of cinema in the 1890s brought to the public a new form of media – the moving image. The apocryphal story of early filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière’s 1896 film “L’arrivée d’un train à La Ciotat” sending audiences screaming out of the theater, believing the on-screen train was going to hit them, may be an often-told myth, but it still demonstrates the sense of reality that early motion picture attendees reported experiencing.

Throughout the 20th century, cinematic developments such as color, sound, widescreen, and 3D added to the content creation toolset, as inventors sought new methods and technologies, first analog then digital, to build realistic immersive experiences. One early attempt was the Cinéorama, devised by Raoul Grimoin-Sanson for the Paris Exposition of 1900, which combined a panorama rotunda with cinema projection to simulate a ride in a hot-air balloon over Paris. Footage was first filmed with ten cameras mounted in a real hot-air balloon, and then presented using ten synchronized projectors, projecting onto screens arranged in a full 360° circle around the viewing platform. The platform itself was large enough that 200 spectators were able to experience the exhibit at the same time.

The 1927 French silent film “Napoleon” by director Abel Gance also used a multi-camera widescreen process. Gance wanted to bring a heightened impact to the climatic final battle scene and devised a special widescreen format, given the name Polyvision, which used three stacked cameras to shoot a panoramic view. Exhibition required three synchronized projectors to show the footage as a triptych on three horizontally placed screens to ultimately display an image that was four times wider than it was high. While the impact of such a wide-screen picture was dramatic, it was technically very difficult to display properly, as projector synchronization was complicated, and there was no practical method to hide the seams between the three projected frames.

In 1939, at the World’s Fair in New York, filmmaker and special effects expert Fred Waller introduced an immersive theater for the Petroleum Industry exhibit, called Vitarama, which used an array of 11 projectors to project a giant image onto a dome-like spherical screen, designed by architect Ralph Walker.

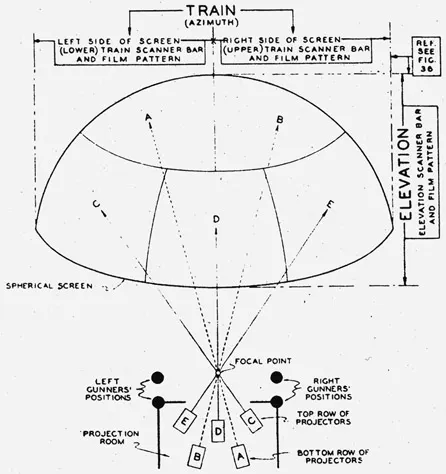

In 1941, Waller took elements of his Vitarama immersive theater and invented a multi-projection simulator for the military. Called the Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer, its purpose was to train airplane gunners under realistic conditions. They would learn to estimate quickly and accurately the range of a target, to track it, and to estimate the correct point of aim using non-computing sights. To create the footage for the machine, five cameras were mounted in the gun turret position of a bomber, and filmed during flight. Combat situations were depicted by having “enemy” planes fly past the cameras. The Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer itself used a special spherical screen designed by Ralph Walker, and five projectors to create a large tiled image that surrounded four gunner trainees. It featured a 150° horizontal field of view and a 75° vertical. The trainees were seated at mock gun turrets and engaged in simulated combat with moving targets. In addition to the visual feedback on the spherical screen, the trainees also received audio via headphones, and vibration feedback through the dummy guns. A mechanical system kept score of their hits and misses and provided a final tally. Waller’s system was used by the US military during World War II, and the first installation was in Honolulu, Hawaii, following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Figure 1.9 Waller Flexible Gunnery Trainer

Following World War II, Waller devised another multi-camera/multi-projector system for entertainment, and named it Cinerama (for cinema-panorama). Similar to the projection used for Gance’s “Napoleon,” Cinerama used a triptych of three projectors, projecting a seamed three-panel image onto a giant curved screen. A special system was designed to shoot for Cinerama, with three cameras mounted together at 48° angles to each other. The interlocked cameras each ...