![]()

Plate 1.1 Wifredo Lam, The Jungle (detail from Plate 1.23).

Chapter 1

Modernism and its margins

Paul Wood

Introduction

This chapter discusses an important aspect of the relationship between European modern art and the arts of the rest of the world. Clearly that would be too vast a subject to attempt to address fully. So here I want to focus on just one key concept, the most influential and the most controversial. Somewhat paradoxically, the main way that early twentieth-century modernism related to the arts of the rest of the world was through the idea of the ‘primitive’. Beginning around 1905, the work of many of the most ambitious modernist artists was marked by an explicit engagement with images and objects from Africa and Oceania. This was underwritten by the then new concept of ‘primitive art’, and what were believed to be its key qualities of authenticity and emotional expression (concepts which, although now displaced from much of the professional practice of contemporary art, remain significant in the wider popular-cultural sense of what art is ‘about’).

The artists involved included, in France, the pivotal figure of Pablo Picasso as well as the Fauve group, featuring Henri Matisse, André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck. Matisse’s Blue Nude of 1907 was subtitled ‘Souvenir of Biskra’, an oasis in French colonial Algeria which Matisse had visited in 1906 (Plate 1.2). The picture’s employment of non-European elements is clear: its background includes palm trees, the nude’s skin is tinged with blue, a colour associated with the Tuareg. And the pose is indebted to sub-Saharan African carvings. It is not however a direct copy, being based on one of Matisse’s own sculptures from earlier that year, which in turn bore witness to his interest in African art.1 In Germany, members of the Expressionist group the Brücke frequently painted and carved images based on African or Polynesian sources, or combined primitive techniques with traditional Christian subjects, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s figures of Adam and Eve (Plate 1.3). The sculptor Constantin Brancusi also adopted direct carving into the material after the manner of primitive art, in search of what he saw as a way to penetrate to the essence of his subject (Plate 1.4). In the Expressionist Blaue Reiter Almanac of 1912, Franz Marc and August Macke wrote on ‘savages’ and masks respectively.2 Emil Nolde identified ‘primitive art’ with ‘absolute originality’, and the ‘intense … expression of power and life in very simple forms’.3 ‘Primitive art’ had an impact on modern art in England through the influence of the modernist critic Roger Fry, who regarded African carvings as embodying ‘complete plastic freedom’ and as ‘possessing an inner life of their own’.4 Many English artists responded, among the best known being Henry Moore, who commented that ‘to discover, as a young student, that the African carvers could interpret the human figure to this degree, but still keep and intensify the expression, encouraged me to be more adventurous and experimental’.5

Plate 1.2 Henri Matisse, Blue Nude (Souvenir of Biskra), 1907, oil on canvas, 92 × 140 cm. The Baltimore Museum of Art, The Cone Collection, formed by Dr Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland, BMA 1950.228. Photo: Mitro Hood. © Succession H. Matisse/DACS 2018.

Plate 1.3 Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Adam and Eve, 1912, carved and stained wood, 170 × 30 × 31 cm. Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart. Photo: © bpk/Staatsgalerie Stuttgart.

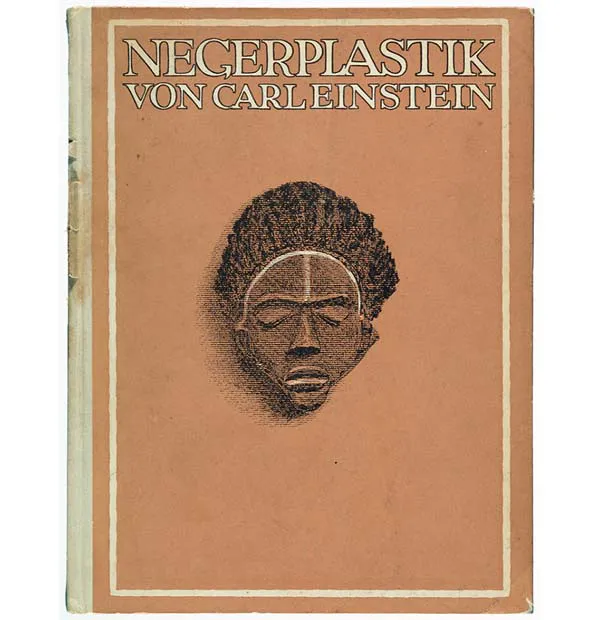

However, during and after the First World War, a different engagement with the ‘primitive’ also emerged, less aesthetic and more overtly political. In the hands of the revolutionary avant-garde, the concept of the ‘primitive’ was used not so much to reinvigorate European art, but as a lever to challenge and destabilise European bourgeois culture. The arts of Africa and Oceania had an impact on the Dada group, active in Zurich and Berlin. Carl Einstein’s copiously illustrated volume Negerplastik (usually translated as ‘Negro Sculpture’) connected the technical radicalism of Cubism with African art (Plate 1.5). After the Russian Revolution, a radicalised understanding of African and Oceanic art impacted on many of those in the orbit of Surrealism, including André Breton, Georges Bataille and the sculptor Alberto Giacometti (Plate 1.6).

Plate 1.4 Constantin Brancusi, Adam and Eve, 1916–21, chestnut (Adam) and oak (Eve) on limestone, height 240 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York. Photo: © 2017. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum/Art Resource, NY/Scala, Florence. © Succession Brancusi – All Rights Reserved. ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2017.

Plate 1.5 Cover of Carl Einstein, Negerplastik, Leipzig, 1915. The Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, VET.GER.IV.B.236. Photo: Bodleian Library.

Long as it already is, the preceding list could be much longer. In one variant or another, during the first half of the twentieth century, ‘primitivism’ was of undoubted importance to the European avant-garde (and here I am using that term in its widest sense, to embrace all tendencies from the most autonomous to the most engaged).6 Much was at stake in the concept of the ‘primitive’, both aesthetically and politically.

Plate 1.6 Alberto Giacometti, Spoon Woman, 1926–27, bronze, 145 × 51 × 21 cm. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York. Acquired through the Mrs Rita Silver Fund in honor of her husband Leo Silver and in memory of her son Stanley R. Silver, and the Mr and Mrs Walter Hochschild Fund. Acc. N.: 158.1986. Photo: © 2017. Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York/Scala, Florence. © The Estate of Alberto Giacometti (Fondation Annette et Alberto Giacometti, Paris and ADAGP, Paris), licensed in the UK by ACS and DACS, London 2017.

1 Primitivism and expression

The avant-garde and ‘perspective’

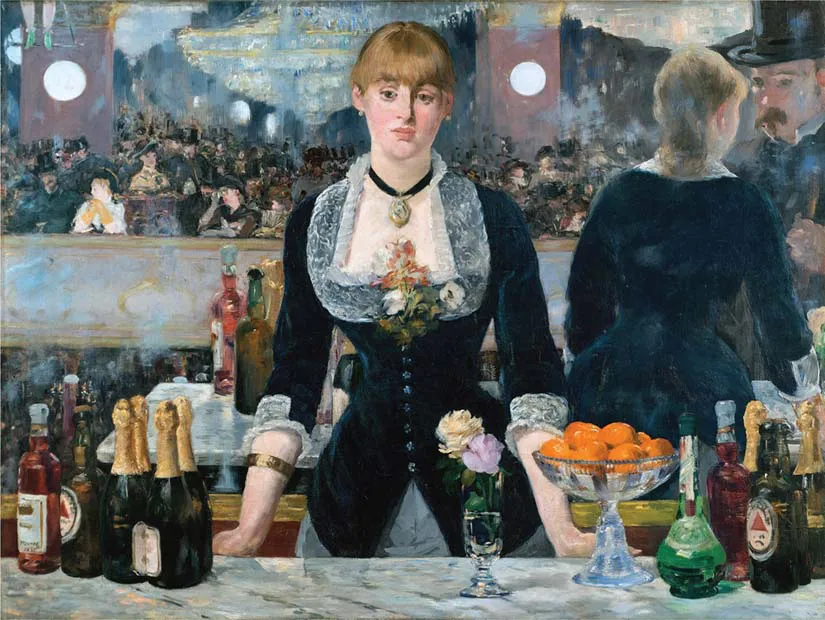

The idea of the ‘primitive’ had not been important for the first phase of the modern movement in the nineteenth century. The main preoccupation of artists such as Edouard Manet, and the Impressionists, had been with their own contemporary world. Centrally, this meant an emphasis on urban subjects and, above all, the radically new urban modernity of Paris (Plate 1.7). Not entirely so, there was also another strand of interest in rural subjects, including both the landscape itself and those who lived and worked in it. But even here, those perennial subjects had to be treated in a modern way.

This points to one of the absolutely key features of avant-garde art, nineteenth and twentieth century alike: the elevation of the means of representation to parity with, or even precedence over, the subjects represented; an escalated tension between the how and the what. For four hundred years, notwithstanding a succession of conceptual, technical and stylistic changes, some form or other of credible lifelikeness had been the hallmark of European art. However baroque the fantasy, however spiritual the subject, the norm was for things to happen within a coherent perspectival space in which illusionistically modelled figures elicited emotional responses from their viewers.

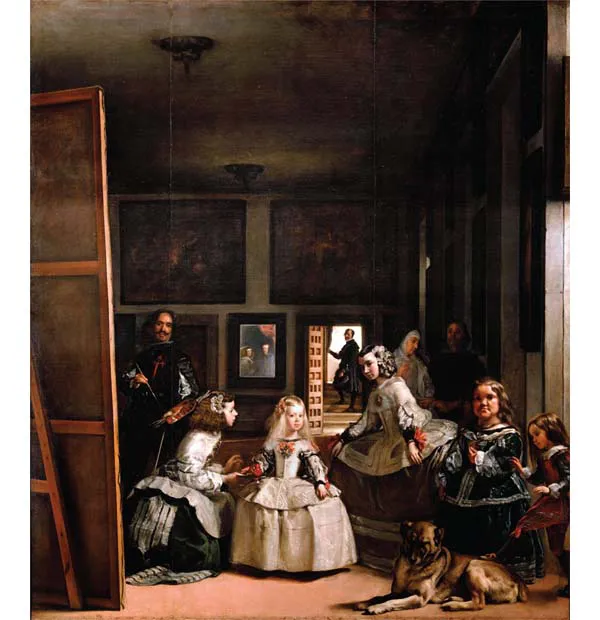

Because perspective simulates something of the way we see the world, it is easy to believe that a mimetic painting offers a ‘window on the world’, or a ‘reflection’ of it. However, perspective does not replicate the way we see the world, and paintings are neither windows nor mirrors. They are artful constructions, and not only do they construct their fictions, they also construct their spectators. The European ‘I’ is strongly bound up with the European eye. Velázquez’ Las Meninas represents a sophisticated meditation on precisely this point (Plate 1.8). In his painting, Velázquez contrived a situation in which the actual subject viewing the picture and the subjects of the picture within its own fictive world become involved in a kind of infinite mutual collapse. For Michel Foucault, Las Meninas, with its apparent compression of the main subjects of the picture that Velázquez is depicted as painting on his easel (the royal couple reflected in the mirror at the back of Las Meninas) and other ‘subjects’ looking at the finished painting (its spectators), amounted to nothing less than ‘representation undertak[ing] to represent itself’.7 But in placing such complex questions about illusion and reality at the centre of its concerns, Las Meninas is an exception which proves the rule. While many ‘old master’ paintings nod to their own artifice for the benefit of a sophisticated spectator, normative perspectival representation is about the provision of seamless illusions. And those in their turn are centrally about the reinforcement of ideas rooted outside the world of art itself, in religion, morality and politics. When they were produced, such paintings were not intended for the limbo of an art museum, but had their being in worlds of power.

Plate 1.7 Edouard Manet, A Bar at the Folies-Bergère, 1882, oil on canvas, 96 × 130 cm. Courtauld Gallery, London. Photo: Ian Dagnall/Alamy.

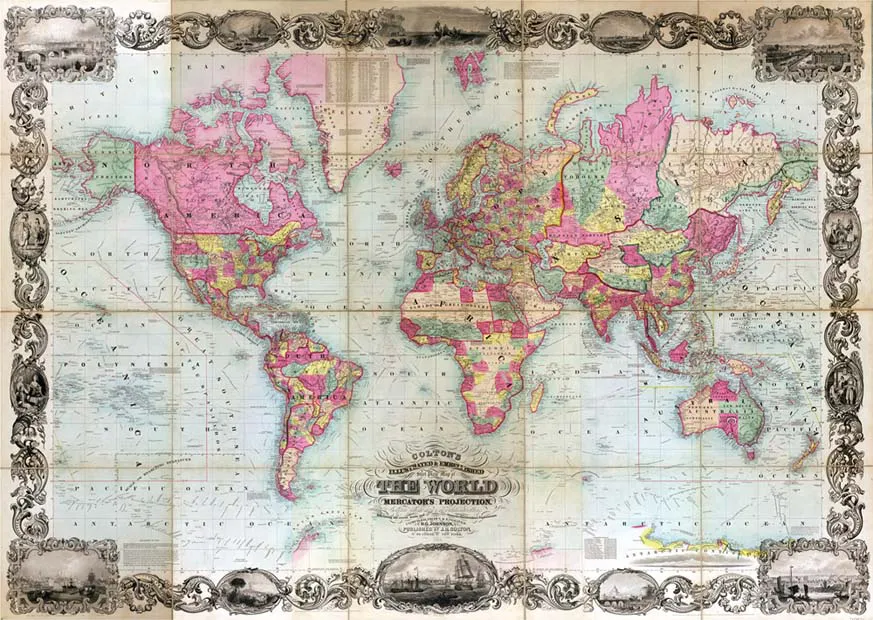

Such links between the illusions of art and the exercise of power draw attention to a related factor. For the kind of projection which orders the fictive world of a pictorial representation is not dissimilar to the kind of projection which orders the physical world in a different kind of representation: maps. The projection can be organised around a monocular ‘vanishing point’, in the case of a picture. Or, in the case of a map of the globe, it is usually organised around a chosen datum line – one of the historically most important being that running through Greenwich (Plate 1.9). Both cases involve organising the space – fictive on the one hand, real on the other – through the device of a network of lines.

Plate 1.8 Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas, 1656, oil on canvas, 318 × 276 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Photo: PAINTING/Alamy.

These lines can be the orthogonals of perspectival representation, ordering the virtual space of the image and confirming the viewer in the place from which he or she ‘owns’ the fiction of the picture. Or they can be lines of latitude and longitude ordering the real spaces of the globe on a map, defining east and west, north and south. In both cases, a system of ordering space enables the positioning – imaginative and moral, as well as spatial – of spectators, of viewing subjects. Along with verbal representations, visual representations construct individuals. To put the matter somewhat schematically, constructions of objective reality and of modern subjectivity are two sides of the same coin.

Plate 1.9 D. Griffing Johnson, Colton’s Illustrated & Embellished Steel Plate Map of the World on Mercator’s Projection: Compiled from the Latest & Most Authentic Sources...