eBook - ePub

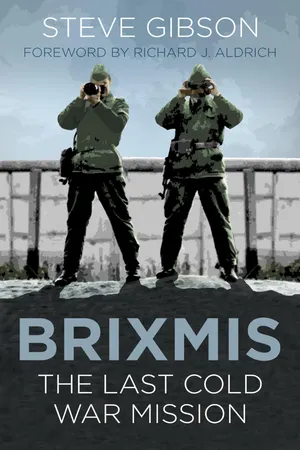

BRIXMIS

The Last Cold War Mission

Steve Gibson

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 400 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

BRIXMIS

The Last Cold War Mission

Steve Gibson

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

BRIXMIS (British Commander-in-Chief's Mission to the Group Soviet Forces of Occupation in Germany) is one of the most covert elite units of the British Army. They were dropped in behind 'enemy lines' ten months after the Second World War had ended and continued with their intelligence-gathering missions until the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989. During this period Berlin was a hotbed of spying between East and West. BRIXMIS was established as a trusted channel of communication between the Red Army and the British Army on the Rhine. However, they acted in the shadows to steal advanced Soviet equipment and penetrate top-secret training areas. Here Steve Gibson offers a new understanding of the complex British role in the Cold War.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

BRIXMIS è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a BRIXMIS di Steve Gibson in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a History e Military & Maritime History. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Argomento

HistoryCategoria

Military & Maritime History1

THE STUFF OF TOURING

THE RULES OF TOURING

Rule One | – | There are no rules. |

Rule Two | – | Think sneaky ’cos sneaky’s best. |

Rule Three | – | Beware the wandering Sov, ’cos he’s the one that’s going to fuck you. |

Rule Four | – | Write it down now. You’ll forget it later. |

Rule Five | – | The truth is a very powerful weapon. There is nowhere to go from the truth. |

‘Kiiiitt!’

The word was shouted; drawn out, extended on the ‘i’ for a good two seconds and ended with emphasis on the ‘t’. The word ‘kit’ was the Mission’s battle cry and it deserved to be emphasised. That such a small word could galvanise an entire crew was astonishing. ‘Kit’ was shorthand for military equipment and the main road between Buchholz and Schwerin was exploding with it. This was the third column of the morning.

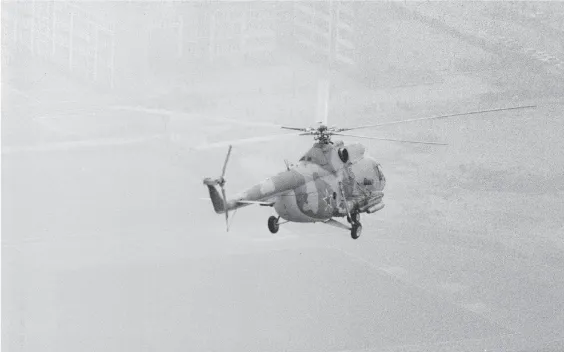

‘HIP-C. Red white outline sixteen, figures one six. Red star markings on tail. It’s Sov1 He’s seen us.’

The infamous HIP-C red white outline 16 being photographed as it returns to Potsdam.

Pete Curran spotted it. He had taken over lookout as Geoff and I prepared for the vehicles coming towards us on the road.

‘Seen. He hasn’t got comms2 with these other guys or he would have stopped them already. Pete, you keep an eye on him. If he lands then we’ll think about moving. I don’t want to be flushed out just yet. Geoff, you keep calling.’

Having Geoff Cotter as tour NCO was like having Electric Light3 and Research4 along with you. A part-time tourer and Intelligence Corps NCO, his main job back in Berlin was helping to run the inventory of all Soviet equipment held in the DDR. As part of Research, his job was to feed collated intelligence on all these vehicles into the database operation. If you gave Geoff a Soviet vehicle registration number (VRN) he would know which unit it came from and where. It was like asking someone to identify the unit and location of a British Army vehicle based solely on its number-plate. Only there were at least five times as many vehicles and registrations to remember in the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany (GSFG) or Western Group of Forces (WGF) as they had recently renamed themselves since the Wall came down.

Geoff was a little rusty on the calling. He knew what the kit was and he could read the Cyrillics but the speed had to be there too, particularly for the number of vehicles that were passing us. Pete Curran, Royal Corps of Transport corporal and driver for this tour, was helping him out, checking our security and changing film for me. Cameras were moving in a production line, a closed loop between him in the front taking out the spent cartridge and loading a new roll and then back to me taking the photos; one every two seconds or less, as the vehicles rolled past. The frequency of the vehicles was too quick for me to handle it alone. We were stationary so his hands were free but never too far from the ignition. The kit was streaming past in hundred-plus vehicle columns. I had all three cameras working the 85-mm lens. Pete was also responsible for keeping main lookout for narks5 or any attempt to block us from the passing columns. The latter was very unlikely as we were in a near-perfect observation post (OP). The columns were travelling south from Schwerin back to Buchholz. As they passed through the little village we were in, they had to negotiate a 90 degree left-hand bend. This bend was joined by a minor road coming into it from the right. Vehicles on the main road had priority over the minor road so there was no need for them to stop. They just swept round the corner. All the better for us.

There was a single reggie6 on the bend. He stood on the far side of the junction on the grass verge, first to make sure the column followed its designated route and second to stop any civilian traffic coming up the minor road. In the fork formed by the two roads a small collection of houses had sprung up, no more than seven or eight, which constituted the sum total of the village dwellings. The Mercedes Geländewagen, or ‘G-wagon’ as it was better known, was concealed up a short narrow alleyway created by the gaps between the houses. Out of the left side we had a three-quarter view of the vehicles as they slowed to make the turn and a view of them disappearing away from us to our front.

There was an 8-ft wall immediately to our left, concealing us from the view of the approaching columns. Several gaps and passageways between the buildings gave us options out to the right and back behind us. The houses were all two-storey buildings, not very high, and although there were not many of them inhabiting this bleak little meeting spot of routes, they concealed us very well and gave us excellent views out. It wasn’t a particularly prosperous or important communications junction. History hadn’t blessed it or blighted its inhabitants with development. It was yet another dreary, paint-free, sleepy little hamlet in the flat open agricultural plains of the north-west DDR, centred on a road junction that proved to be a major landmark for military traffic heading north out of Potsdam or south back to it. There was no one around in the village. They were all out working by now, so there was no attention drawn by locals either staring at us or coming to talk to us.

Regrettably, there was no cover from the view of the helicopter above. It was uncommon to be observed from the air during a road move. However, it was normally only an inconvenience and rarely a deterrence. Frankly, without landing, whoever was on board the helicopter could do little about us. They were unlikely to have comms with many vehicles on the ground and would therefore find it difficult to target anyone onto us.

It was the first day of February 1990, a clear, bright but very cold day. We had been in the OP for about four hours having spotted the reggies being ‘put out’ at about 6 a.m. It wasn’t this particular reggie that had caught our attention initially but it was this one who had influenced the choice of OP. He seemed singularly uninterested in us as we drove past him. That, together with the fact that it offered good cover and an excellent shot of the targets as they slowed for the bend, made it the junction we would watch.

We had firkled7 our way back into the hamlet across country, out of sight to him on our final approach into the OP. He couldn’t see us now for the houses. As far as he was concerned, if he had registered us at all, we were long gone down the road. The drivers of the vehicles couldn’t see us either because we were positioned out of sight as they approached the turn. As they drew level with us they were concentrating on making the turn and as they rounded the corner we were behind them looking at their rear ends. The vehicle commanders, those who were awake on these long route marches across East Germany, were too busy making sure their vehicles turned without damage to notice us. If any of them did choose to glance behind as they cornered they would have had to have been very quick to take in a G-wagon backed into the shadows, understand who it was and then take the decision to stop their vehicle and have the column apprehend us. The ensuing snarl-up would have given us ample time to exploit the confusion, take one of the side alleys right, out to the adjoining main road and away, returning to this or another OP at a later time for a different column. The other option would be to simply pull forward, turn left and join the main road travelling against the flow of vehicles, the advantage here being that we would not have lost any vehicle shots while moving. It was a great OP. It had good escape routes and was almost fully concealed from the target. The helicopter was just a nuisance but it was distracting and upset the calm. It gave us one more thing we could have done without worrying about.

Waving and smiling was practised on the very youngest members of the DDR . . .

. . . until they become graduates of our course!

There was a break in the columns. We moved forward 10 metres beyond the wall to give ourselves a clearer view up the road to our left and allow a precious few extra seconds lead time to prepare for approaching vehicles. The odd East German civilian vehicle came past. One of them saw us in our slightly more exposed position. We waved and they waved back.

It was customary practice for tour crews to wave at anyone and everyone. Over the years a huge psychology had been built up around waving. First, it was a friendly gesture and generally put people off their guard. By waving to them, it made them think twice about exactly who you were: then you were gone before they could react. Second, it took the onlookers’ gaze away from activity inside the G-wagon to the top two corners of the front windscreen. This detracted from the more suspicious work going on inside the vehicle, whether it be the tour officer taking photographs, the video set up on the pole, or facial gestures and signals that could be read and interpreted by other more careful observers. All hand signals, indications of direction and equipment adjustments were done below the dashboard. Third, the reaction to a wave told us a lot about the wavers. If an East German civilian waved back with a full smile it meant that they knew who you were, had probably seen you before, knew what you did and wished you the best of luck in stuffing the Sovs at their own game. If it was a rueful smile or a slightly forced sheepish grin, it meant the same but without the good luck. Rather, it meant, ‘I know what you are doing but I can’t do anything about it’. If there was no reaction it usually meant they didn’t have a clue who you were or what you were doing and why the hell were you waving at them in the first place. Much the same reaction you might get from waving at someone you don’t know. They would probably spend the next few days trying to work out who it was.

We waved at everyone, from Soviet officers to East German schoolchildren. We particularly concentrated on the children. We waved at them long and hard, forcing them to wave back at us. Most didn’t need prompting. They loved it. Some of the tour NCOs had red noses in the tops of their tour bags ready to whip on every time we passed a group of schoolkids. It made them roar with laughter. We knew that they were being indoctrinated against us at an early age so we figured the sooner we tried some psychological adjustment ourselves the better. Furthermore, it would irritate any Sovs or hard-nosed East Germans when we could get their kids to smile as the adults shook their fists. The wave was a very powerful weapon. This simple gesture could get ordinary people on our side, deflate the authorities who witnessed it and also prepare the kids for future generations of pro-Mission touring.

Inevitably there was a converse reaction. Some Soviet and East German soldiers would respond aggressively. The slower ones would wave first and then shake their fists once they recognised who we were, making us howl with laughter. East German civilians who shook their fists were either part of the establishment or narks. The narks had their own peculiar set of reactions to the wave. They either violently returned the gesture, using the expressive Western single digit sign that gave them away as having been privileged enough to watch too many American films, or they would look away as though they hadn’t seen us at all.

The latter were particularly amusing and we had a very satisfying way of getting our own back on them without resorting to violence. We might be quite innocently and legitimately pulled up next to them in a traffic queue in town. Despite frantic waving and knocking on windows they would completely ignore us. It wasn’t that they were intensely ...