![]()

1

The menopause

A bio-psycho-social transition

What is the menopause?

The menopause occurs on average between the ages of 50 and 51, in most Western cultures, and literally refers to a woman’s last menstrual period. The term originally comes from the Greek words ‘menos’ and ‘pausos’, which mean ‘month’ and an ‘ending’. In this case, the ‘ending’ refers to the cessation of ovulation – the production of fertile eggs or ovum – and therefore fertility, and it also marks a change in life stage for many women. Most women will go through the menopause if they live long enough, although for some the timing of the menopause is influenced by surgery or disease. Hot flushes and night sweats (the medical term for these is ‘vasomotor symptoms’) are the other main physical signs of menopause.

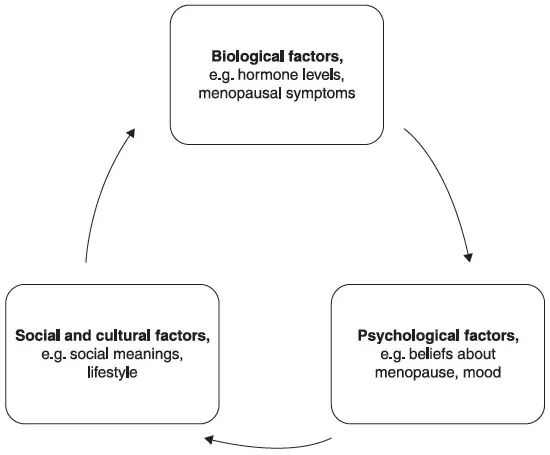

The last menstrual period takes place within a gradual process of physiological change, occurring at the same time as other age-related changes, and within varied social and cultural contexts. Consequently the menopause happens at several levels – the biological, psychological, social and cultural (Hunter and Rendall 2007). Perhaps because it typically occurs at the age of 50, a time when traditionally children leave home and elderly parents may need more care, the menopause has been associated with role and social changes for women. However, this is not necessarily the case for everyone. As we will see in the following sections, what is happening in a woman’s life can influence how she feels about approaching the menopause. The menopause is influenced by biological, psychological and social factors (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 A bio-psycho-social model of factors influencing experience of the menopause.

For example, for one woman the menopause meant that she no longer had to deal with having heavy periods, and this was a relief to her; for her friend, however, whose night sweats had woken her every night and disturbed her sleep for several months, the menopause felt like an ordeal. Similarly, for a woman who is planning to have children in her 40s, an early menopause is likely to have a major impact, whereas for a woman who has already had her family, the issue of fertility may be less relevant.

Some definitions

Menopause is defined as the permanent ending of menstruation and is said to have occurred when a woman has not had a menstrual period for one year. However, the hormonal changes that accompany menopause actually occur over a number of years. The definition of the menopause most widely used by doctors and in research until recently is based on that of the World Health Organization (1981) and refers to the menopause as the ‘permanent cessation of menstruation resulting from loss of ovarian follicular activity’ – meaning that menstrual periods end because the ovaries stop producing eggs. The stages of the menopause transition are generally based on patterns of menstrual periods:

- Premenopause is defined by regular menstruation.

- Perimenopause includes the phase immediately before the menopause and the first year after menopause and is defined by changes in the regularity of menstruation during the previous 12 months.

- Postmenopausal women are those who have not menstruated during the previous 12 months.

It can be difficult to fit all women easily into this menstruation-based classification, however; for example, if you have had a hysterectomy (removal of the womb), had surgery to remove your ovaries or are taking hormone therapy, you will not be having natural menstrual periods. Women in these categories tend to be classified separately because, for them, menstruation would not be a reliable indicator of menopause.

In 2012, the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) created a better system to describe stages of reproductive ageing across the whole life cycle (Harlow et al. 2012). It is based on current evidence and reflects the parallel changes in menstruation, hormonal changes and experience of hot flushes and night sweats across women’s lifespans.

The term ‘perimenopause’ is commonly used to refer to the menopause transition and early postmenopause since this is the stage during which most physical changes occur. The STRAW definitions have also increased our understanding of when menopause occurs and how long it typically lasts (see below).

Stages of Reproductive Aging (STRAW) definitions

- Reproductive stage: includes menarche (onset of menstrual periods) with variable menstruation initially; it can take several years for regular menstrual cycles to develop, and these are usually every 21–35 days. Across this phase – typically from adolescence to late 40s – fairly regular menstruation continues, but there can be some changes in flow (sometimes becoming heavy) and in the length of the cycle.

- Menopause transition: includes early transition (regular menstruation but changes in menstrual cycle length) as well as late menopause transition (two or more missed menstrual periods and at least one interval of 60 days or more between menstrual periods), which happens one to three years before the final menstrual period. During this stage follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels tend to rise (this hormone is working hard to try to produce ovulation) and oestrogen levels start to reduce. Hot flushes are likely to occur during the late menopause transition.

- Menopause: the last menstrual period (LMP).

- Postmenopause: this stage is divided into early (up to six years after the LMP) and late (the subsequent years). Early postmenopause is characterized by hormonal changes and hot flushes, which tend to stabilize during the late postmenopause.

Additional terms – such as ‘climacteric syndrome’ and ‘menopause syndrome’ – have been used, mainly by doctors, to refer to a range of physical and emotional experiences that may or may not be related to hormone or menstrual changes. These include hot flushes, vaginal dryness, loss of libido, depression, anxiety, irritability, poor memory, loss of concentration, mood swings, insomnia, tiredness, aching limbs, loss of energy and dry skin. These will be discussed in later sections but – apart from hot flushes, night sweats and vaginal dryness – these general symptoms are not necessarily a result of menopause and, if they occur, may well have other causes, such as stress, ageing and lifestyle.

‘The change’ or ‘change of life’ is a commonly used term in Western cultures, reflecting the view that the meaning of the menopause is closely associated with general psychological and social adaptations women experience at midlife. ‘Midlife crisis’ also suggests that this stage might coincide with dramatic changes in personal and social relationships and with life events such as illness, caring for (and the death of) parents, dealing with adolescents and children leaving home, as well as reaching the age of 50. Women often review their lives at this age and have existential thoughts about the past and the future, which are of course quite normal. Whether these changes are experienced as a result of the menopause, or are linked to it, will vary between women and will in part be a function of what is happening in their lives, as well as the social and cultural meanings of ageing and menopause.

When does it happen and how long does it last?

Remember that the menopause can occur quite normally during a wide age range – at any time between 40 and 60 years, in fact. Studies have found that in some parts of the world, however, women experience the menopause slightly earlier. For example, in India and Pakistan, menopause age ranges from 44–48 years (average 47 years), compared with 50–51 in Europe and North America. Earlier menopause has been associated with poverty, poor nutrition and smoking (Freeman and Sherif 2007; Andrikoula and Prevelic 2009). Menopause is considered early, or premature, when it occurs in women aged 40 or younger, and this is estimated to affect approximately one per cent of women (Panay and Fenton 2008). The causes of early menopause are often unknown but early menopause can be caused by certain genetic conditions, as well as some autoimmune disorders. Menopause also happens earlier as a consequence of surgery (surgical removal of the ovaries, or oophorectomy), medical treatments, such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy, or some hormone treatments, which interfere with natural hormone production. Medically induced menopause, if not caused by surgery, can be permanent or temporary. This can be the case for women who have had chemotherapy to treat breast cancer. So if this has happened to you and you are uncertain about your menopausal status or fertility, do discuss this with your doctor.

If you have had a hysterectomy, you will not be having menstrual periods and so it can be difficult to know when you have reached the menopause. If you still have ovaries, you will go through the menopause at roughly the same age as other women. However, there is some evidence that women who have had a hysterectomy have a slightly earlier menopause on average than those who have gone through this stage naturally (Siddle et al. 1987). If you are having a hysterectomy, it is important to be clear about the difference between this operation (surgical removal of the womb) and surgical removal of the ovaries (oophorectomy) as the consequences are very different. Oophorectomy does cause menopause and rapid hormone changes, which can lead to more severe hot flushes if not treated. Women who have had surgical menopause and those who have early menopause are generally advised to use HRT until the natural age of menopause, i.e. 50 years.

Typically the duration of the menopause has been thought to be between two and five years, but how long the menopause lasts depends on whether we are thinking about hormone changes, menstrual cycle changes or the experiencing of menopausal symptoms. The STRAW definitions show that these changes occur over an extended period and in different stages; for example, hormone changes tend to begin earlier than menstrual changes and hot flushes. The results of recent studies suggest that the duration of the menopause may also be longer than was previously thought. In a 13-year Australian study (Col et al. 2009) following women through the menopause, the average duration (from the onset of menstrual changes to the stopping of hot flushes) was five to six years. In one of our own UK studies, some women were still having hot flushes and night sweats in their late 50s and early 60s (Hunter et al. 2012). However, we found that this was partly explained by women who had begun using HRT and then stopped: they were more likely to experience hot flushes later as their bodies adjusted to the lowering of oestrogen levels.

Is there a male menopause?

The term ‘male menopause’ is often used in the media to explain a range of symptoms experienced by middle aged and older men, such as low libido, impotence, tiredness or depression. As for women, the term has negative connotations and is often used as a jokey insult. ‘Male menopause’ suggests that the symptoms noted above occur as a result of a sudden drop in the hormone testosterone during middle age. This is not the case, however: testosterone levels reduce very gradually as men age, in fact, and the decline is steady at about one to two per cent each year from around the age of 40. Low levels of testosterone can sometimes be responsible for symptoms when the testes are not functioning properly but this is quite rare, affecting an estimated two per cent of men.

In most cases the symptoms are nothing to do with hormones, and, just as for women, lifestyle factors, age or stresses – such as work or relationship issues, divorce, money problems or ageing parents – are more likely causes (McKinlay et al. 2007). Similarly, midlife can be a time of reflection or anxiety about ageing and accomplishments. Interestingly, the trend to diagnose ‘male menopause’ was related to the availability of synthetic testosterone, which came on to the market in the 1930s. However, testosterone was not very successful in treating impotence, so it was subsequently aimed at other symptoms such as tiredness and depression. Male menopause was renamed ‘andropause’ in the 1990s, at about the same time that impotence was re named ‘erectile dysfunction’ and treated with Viagra (Watkins 2008).

Why do we have menopause?

In contrast to other species, human females are unusual in that their reproductive ageing happens on average well before other age-related physical changes. Most animals and birds continue to reproduce throughout life. Some animals, particularly non-human primates and animals such as elephants that have long lifespans (especially if living in captivity), have varying lengths of post-reproductive life. In general, however, amongst non-human primates infertility is associated with advanced age. Even chimpanzees, our closest relative, reach this reproductive stage anytime between mid-age and death depending on how long they live. So why are humans different in this respect? There are no definite answers but two main theories have been proposed. These can be summarized as (i) non-adaptive theories (Finn 2002) and (ii) adaptive theories (Rashidi and Shanley 2009).

Non-adaptive theories suggest that the menopause happens because of two non-adaptive evolutionary developments. First, because we have a large but limited supply of eggs at birth; and second, because we have a considerably longer lifespan than other mammals of similar size. As a result, we run out of eggs by mid-age, at a time when other physical systems are ageing much more slowly.

In contrast adaptive theories suggest that menopause confers benefits; for example, postmenopausal women avoid the dangers of childbirth, which are more common with increasing age. One main theory emphasizes the role of the mother, and another the role of the grandmother, in supporting the next generations. The mother theory focuses on the unusually long duration of child development in humans – and therefore the time women need to raise children – which is much longer than for other animals. So women need an extra 15 years or so of life after their last child is born in order to nurture their offspring. The grandmother theory emphasizes the evolutionary benefits of having a grandmother to assist mothers with childcare and the care of other children. It has even been suggested that the evolution of the menopause has been important in extending our lifespans due to increased support for younger generations and reduced reproductive costs, for example, those related to childcare. We still do not know for sure why we have menopause but this latter theory in particular seems to suggest there are some benefits to it.

Biological changes

The menopause is triggered by hormone changes. However, hormone production is influenced by a complex system of interactions between the ovaries, our hormones and the brain (Burger 2006), the hypothalamo–pituitary–ovarian axis. The main hormones produced by the ovary are oestrogen (oestradiol), progesterone and testosterone.

During the menstrual cycle, hormones are sent directly into the bloodstream from the ovaries, as well as from the adrenal glands (which are just above the kidneys). The pituitary gland at the base of the brain releases a follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and a luteinizing hormone (LH). FSH and LH cause the ovaries to release oestrogen and progesterone. In a feedback loop, the levels of oestrogen and progesterone in the bloodstream then regulate the amounts of FSH and LH that are produced. So during a regular menstrual cycle, this system adjusts and regulates the amounts of hormones in the body. During the first half of the menstrual cycle, FSH causes the egg (ovum) to develop and mature, and oestrogen levels rise. Ovulation (which occurs when the egg leaves the ovaries) is triggered when oestrogen reaches a certain level in the bloodstream and this causes the pituitary to produce LH. If pregnancy does not occur, levels of oestrogen and progesterone fall and the lining of the womb is shed. Menstruation occurs and the whole cycle continues again...