![]()

Part One

SOUTHERN EUROPE

![]()

Chapter 1

MANY EUROPES

I Southern Europe?

Is it legitimate to define the countries which border the northern shores of the Mediterranean as ‘Southern Europe’ and to distinguish the area thus formed from the rest of Europe? This is not an idle question. Today the individual characteristics of each of the countries which make up Europe are known to everyone. When the Maastricht Treaty was signed in 1992, it seemed that the unification of Europe could be carried out easily. The treaty spelt out the time-frame for arriving at the single European market. However, since then not only has economic integration proved to be very difficult but the political differences between the various European countries have become more marked. Conflicts of interest and opinion have become stronger. Because of this, it is important to understand why and how these conflicts arose and to find a solution that can reconcile the emergence of strong nationalist feelings with the sought-after harmony of a united Europe. The understanding of each country’s specific identity can be useful for the creation of common institutional, social and economic policies.

Even if we can no longer think of ourselves as just Europeans, we can try to understand the reasons for these feelings and we can work more efficiently if we have a greater knowledge of our differences, contrasts and even similarities. Perhaps the moment has arrived to accept that, between the overpowering rise of national identities and a European identity, it is possible to feel oneself subject of only a part of the culture and history of Europe. Once we used to think that we could be citizens of the world, but we are not yet citizens of Europe, and we are no longer just citizens of our own country. This indicates that one single Europe does not exist: many Europes do.

It is not easy to understand the reasons for the different experiences of each sub-area of the European continent. The differences and similarities between areas formed by specific groups of nations are based on various factors. I plan to discuss these distinguishing factors one at a time. The following pages will analyze in more detail the points presented in this introduction.

II An introduction to the socio-economic formation of Southern Europe

There is little doubt concerning the vital importance of the choices made in international politics after the Second World War. After the fall of Soviet power in 1989, these were debated once again. But until that moment Portugal, Spain, Italy, Greece and Turkey had shared, in different measures, the common fate of forming the group of countries confronting the countries of the Warsaw Pact on the Southern European and Middle Eastern flank of Nato. The consequences of this position have been both politically and economically important. However, international politics could not exert enough influence on Southern Europe in such a way as to shape its experience. Southern Europe has specific characteristics that are rooted in a socio-economic structure different to that of Continental Europe (including the British Isles), Central Europe and Eastern Europe. The long- and short-term historical differences of the last two areas vis-à-vis the Southern European area are immediately evident, while they become less so when looking at Continental Europe and Great Britain. A fairly simple way of analyzing the question is to look at OECD1 statistical data gathered over the last thirty years.

However, one thing must be made quite clear: not all the countries of Southern Europe are on the Mediterranean nor are all the Mediterranean countries part of Southern Europe. Those countries which, until a short time ago, formed Yugoslavia are not part if it. These have a completely different history from Italy, Portugal, Spain, Greece and Turkey. Slovenia, Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia Hercegovina share their history with Central and Eastern Europe not only because of ancient roots but also because they are among those countries which followed the Soviet example after the Second World War, thereby rejecting the possibility of a capitalistic economy and a democratic parliamentary system. From this point of view, the conflict which started in 1948 between the then Yugoslavia and the USSR is not important as it does not alter the problem. On the other hand, France is a typically Continental European country with its own clear and specific identity, and is not part of Southern Europe. Braudel was very explicit on this subject when he wrote:

Since the time of Caesar, and well before, up until the great barbarian invasions in the Fifth century, the history of France was a fragment of Mediterranean history. The events which occurred around the middle sea, even if they happened a long way from the shores of France, determined the country’s life. But, after the invasions (leaving aside the exceptions like the belated wars for the domination of Italy), France identified with, above all, Central and Eastern Europe.2

The most important difference between the countries of Southern Europe and those of Continental Europe and the British Isles is the early industrialization of the latter.

The following figures and tables regarding social structure show a whole series of consequences following the late industrialization of Southern European countries. These figures and tables relate to four separate periods covering the years from 1960 to 1989, and they allow comparisons between the group of Continental European countries formed by Germany, France and Great Britain, and the countries of Southern Europe.

Data for the years immediately following the Second World War is not included here as too many different methods of data collection were used. Methods became standardized in 1960.

The data on which the figures are based can be found in Appendix I together with other statistical data.

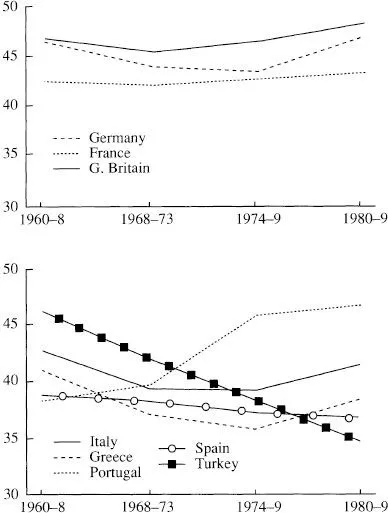

Figure 1.1 shows that Germany, France and Great Britain had more labour force as a percentage of total population than all of the Southern European countries – with the exception of Portugal where, in the second half of the 1970s, the labour force was larger than in the other southern countries.

Fig. 1.1 Total labour force as percentage of total population (average for period)

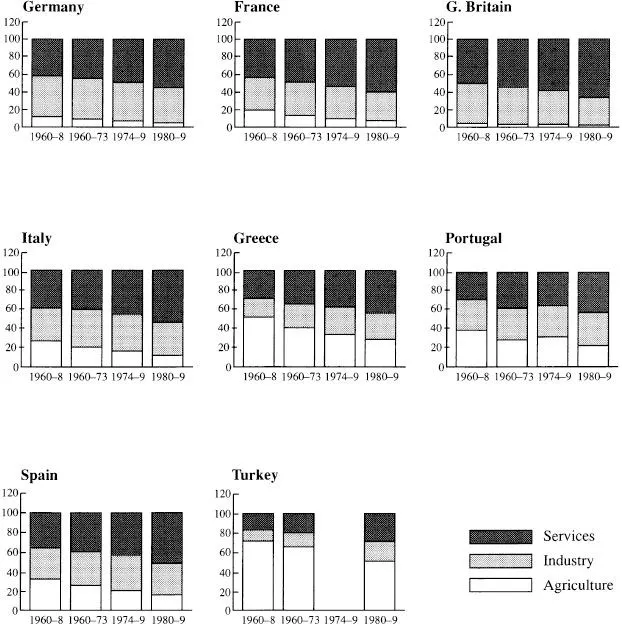

The most significant figures are those relating to the percentage of workers in agriculture, in industry and in the service sector (Fig. 1.2).

Southern Europe not only had a slower rate of decline in the number of agricultural workers but, excluding Italy, very high percentages were reached for the service sector workers without prior peaks of employment in industry, which is an experience typical of Germany, France and Great Britain.3 This peculiarity of the southern experience starts to lose its relevance, except in the case of Greece and Turkey, over the last period (1980–9).

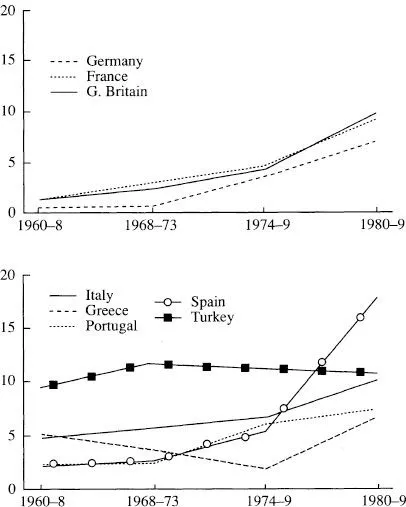

Until the 1980s, total unemployment (male and female) was higher in the Southern European countries (Fig. 1.3)

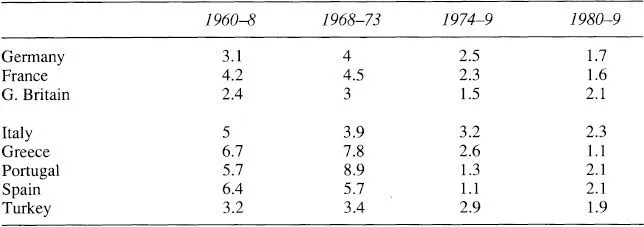

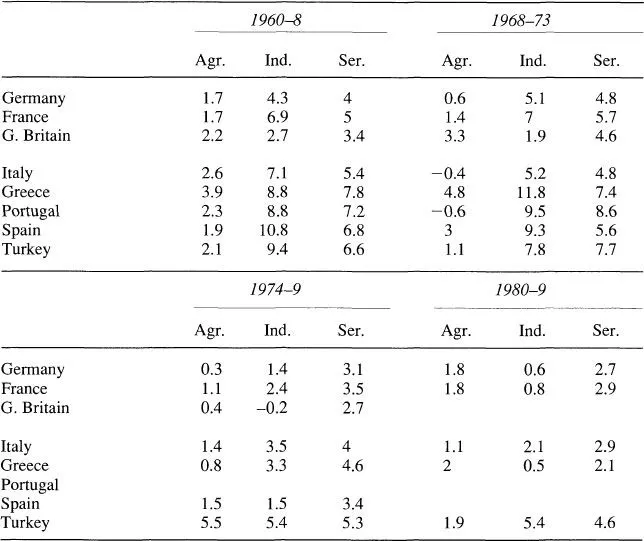

The reason for the jump from agriculture straight to services lies in the non-growth mechanism in force since 1968–73 (excluding Turkey) and, at the same time, in the fall of GDP per capita also in Germany, France and Great Britain. This non-growth mechanism is clearly shown by the trend in the yearly percentage changes of GDP per capita (Table 1.1) and of value added in agriculture, industry and services (Table 1.2) for the four periods.

Fig. 1.2 Employment by sector as percentage of total employment (average for period)

The data shows that the country with the strongest growth indicators is Turkey. The reason for this is the low level of the starting point and the impressive economic structure of a social system still solidly based on agriculture.

Most Europeans do not consider Turkey as part of Europe. But Turkey can lay claim to being European not only because of international and military alliances but also because it has achieved a system of parliamentary democracy (of European origins) which has no equivalent in the Middle East.

The common element which emerges in the countries identified as South European is the rapid growth and the rapid change from a mostly agrarian society to one strongly oriented towards the service sector. The peculiarity of this development emphasizes a very important aspect of the socio-economic structure of these countries. The following pages will show that these societies have not been able to reach a high and stable systemic integration which could mirror the slow and constant changes in their social structures. They have been shaken up by convulsive contradictions over a very short period. In spite of the contemporary displays of intense, violent and armed political and social conflict,4 all the countries examined here have developed, however, a remarkable capacity for social integration. Following Lockwood’s theory,5 they have been able to establish non-conflictual relations between social groups.

Fig. 1.3 Unemployment as percentage of total labour force (average for period)

Table 1.1 GDP per capita – yearly percentage changes (average for period)

Source: OECD – see Ch. 1, n. 1.

Table 1.2 Value added – yearly percentage changes by sector (average for period)

Source: OECD – see Ch. 1, n. 1.

Considering the intense process of change that these countries have gone through, social mobility in Southern Europe has not been as intense and constant as could have been imagined. The aim of this book is to show that the actions of individuals are marked by individualistic and vertical relationships rather than collective and horizontal ones. Southern Europe is a land of clientship and patronage and is characterized by the presence of status systems not by contractual ones. Late industrialization, insufficient penetration of market mechanisms and the over-whelming presence of the state in social and economic life are all factors which have been decisive in forming the economic and social life of these countries.

III Agrarian society and the persistence of traditions

Italy was the first of the Southern European countries to be integrated into an institutional system of international free trade which was one of the characteristics of its post-war economic, social and political history. Italy was a moving force with its very strong level of integration both with Continental Europe and with international trade. The increase in the latter is one of the main causes of the economic development in the second post-war period. Another factor which sets Italy apart from the other Southern European countries and societies is the lateness with which the others joined the EEC. As we all know, this process is still unfinished mainly because of the monetary policies which have been pursued.

However, this process has thrown light on the profound differences within Europe. We will see that these were largely determined by a general process which is not primarily economic but institutional and social, or rather, political. The late creation of market economies has been a distinctive element in Southern Europe’s history since the end of the Second World War. But market forces have been implemented from above: from the institutional system rather than from the foundation of society. First in Italy, then in Spain, Greece, Portugal and finally Turkey, the protectionist, restrictive, administrative trappings which burdened, and which in some ways still burden, the economies of these countries were dismantled by decisions made by their political elites. This was not due only to the external shocks imposed by the international economic situation, nor was it a functional adjustment of the social sub-systems to the invisible hand of a self-regulated market. Instead, it was a specific, differentiating and suffered process in which both the role of the modernizing elites and the legacy of the past acted to define the framework in which to operate. The culture of the management groups and the personal creed of the protagonists of the large collective mobilization movements were essential in shaping this process.

The agrarian vicissitudes of the Southern European countries bear witness to this. In the first place, the importance of the landowning structure was one of the characteristics which shaped the history of three of these countries: Italy, Spain and Portugal. But the way in which the advance of capitalism in the rural areas influenced economic growth and social change was different in each of these three countries.

In the south of Italy the absentee landlords had, for centuries, influenced the relations between agrarian structure and economic growth. After the Second World War the collective movement of farmers from below and political reforms from above, transformed the large estates into small- and medium-sized holdings and into capitalistic leaseholdings, freeing a part of the labour force for the increasing industrialization of the country and for internal and external emigration. In Italy there was agrarian reform without a social revolution.

In Spain dormant estates transformed themselves into engines of capitalism thanks to the flight of the workers from the rural areas and to the virtuous circle created by increases in labour costs and mechanization, aided by the progressive dismantling of the administrative trappings.

In Portugal inertia was an age-old fact in a millennial balance, both in the estate-owning south as in the small-holding north. The military revolution gave rise to the rebellion of the seasonal labourers and the political mobilization which destroyed the dominance of the estate-owners. When the collective enthusiasms had died down and the soldiers had retreated to their barracks, the agrarian counter-revolution and democratic political reform laid the basis for the creation of a system of large, medium and small capitalistic holdings in the south of the country.

But the most characteristic thing about Southern Europe’s agrarian vicissitudes is the polarization of its land property structures. While the north of Portugal was made up of small-holders, who played a decisive role in repelling the military and communist revolution of 1974, the south was made up of large estates. The same can be said of Galicia, Euskady (the Basque provinces) and Catalonia which were in contrast to Castile and Andalusia. If a comparison is made between the large and medium-sized capitalistic agrarian concerns and the small family-run farms, this heterogeneity and difference in the structure of landowning is still characteristic of Italy. In Greece and Turkey the small farm system has been fully developed as a result of the political choices made after the fall of the dominant Ottoman landownership. Those choices made the Greek agricultural sector the basis of consensus of the oligarchic dominion of the ruling classes. The case of Turkey is different. In spite of the lack of agrarian reforms after the Second World War, the Turkish farmers were stronger and were backed by the state, by technology, by availability of credit and by non-taxation (as in Greece) in order to increase the value of family property and to favour the merging of medium- and small-sized farms, while the depopulation of rural areas and emigration continued.

The persistence of family-run farms and small-holdings can be understood only by considering the writings of Chajanov,6 the most important social scientist in the field of agrarian history. The study of his theories on family-run farms enables us to appreciate the exceptional role played by this economic form, which many considered confined to an out-dated tradition, in the pursuit of modernity.

The agrarian vicissitudes of Southern Europe have other points in common. One of the most remarkable characteristics of the Southern European countries, when compared to those of Continental Europe, is the importance that agriculture had on their overall economic potential. The agrarian society, with its wealth of values, its close family ties, with its sharing of specific social mores, has not only resisted the spread ...