![]()

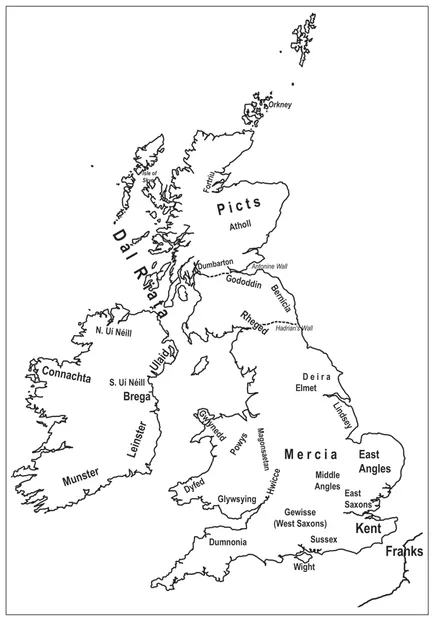

Map 1 Britain and its neighbours c.600

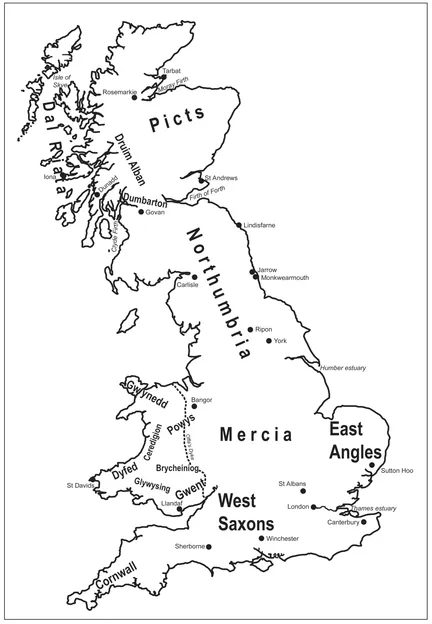

Map 2 The kingdoms of Britain c.800

(with some ecclesiastical and other sites)

![]()

Introduction

This book which covers the period c. 600–800 is the opening volume in a series which aims to study the interrelationship of religion, politics and society in Britain up to the present day. For the period c.600–800, which is the subject of this volume, the links between religion and other facets of the history of the time have always tended to play a major role in studies of it, because most of the written sources on which historians are dependent were produced by churchmen or churchwomen, and so many other aspects of society have perforce to be studied through the opinions of these literate specialists. The range of sources is limited in number and scope, particularly compared to what is available for the later periods of Britain’s history, and the problems arising from that produce various distinctive characteristics in the study of the period. Early medievalists have to work very closely with the written sources that have survived and much can depend on the nuanced reading of a relatively short passage of text. Direct use of primary sources is therefore a feature of this volume, and a large part of this introduction is devoted to identifying the major classes of evidence and to examining the work of three authors – Gildas, Adomnán and Bede – who are cited extensively in later chapters.

Not the least of the problems with the sources in the period c.600-800 is that not all classes of society nor all areas of Britain are represented equally in what has survived. The problem is particularly acute for the people who inhabited much of northern and eastern Scotland, the Picts, for whom no written records are extant that were produced within Pictland itself except variant versions of a king-list. The Picts are referred to in records produced by their neighbours but, as will become apparent, many details about Pictish political and social organisation remain obscure. Fortunately there are alternative ways of approaching the period through non-written sources of evidence such as archaeological data, sculpture and place-names, and frequent use will be made of such categories of material in the following pages. But anyone seeking to understand the period has to begin by appreciating that they have to live with uncertainty on many key issues. If one enjoys working on the early middle ages it is this very incompleteness of the record that provides part of the fascination as one strives to make sense of apparently contradictory pieces of evidence, but for a newcomer it can be initially disorienting.

The traveller to the period c.600–800 has to accept that not only will there be certain aspects of its history that will probably never be fully comprehended, but also that much of what can be known will be unfamiliar. The political map of Britain in this period, for instance, bears little resemblance to that of later periods. Although it can be convenient to refer to England, Wales and Scotland as geographical areas to help orient the reader, it must be appreciated that they did not exist as political or administrative areas at the time, even if the seeds of their emergence as distinctive political and cultural units do lie within the period. Contemporary writers identified four distinct people as living in Britain c.600–800 – British, Picts, Irish and Anglo-Saxons. The British and Picts were indigenous inhabitants whose ancestors were living in Britain during the Roman period. The end of Roman control around the beginning of the fifth century was followed by incursions of Anglo-Saxon and Irish settlers into certain areas of the country, though it is possible that Irish settlements in various parts of the west may go back somewhat longer. We can identify certain territories as being under British, Pictish, Irish or Anglo-Saxon control by 600 (Map 1), as long as one does not demand precision over the exact course of boundaries. However, the political map was not stabilised at this point and, as will become apparent in the more detailed discussion of the four peoples in Chapter 1, major changes in the political geography occurred between 600 and 800 (Map 2). It is also not possible to study the period 600 to 800 without appreciating something of what occurred in the turbulent centuries between 400 and 600 when the inhabitants of Britain, like those of other former areas of the Roman empire, had to adjust to life in a post-Roman world. Therefore Chapter 1, which provides an overview of the political and social structures within early medieval Britain, reaches back into the fifth and sixth centuries to seek to explain the origins of structures that continued to evolve in the period after 600. However, it should be noted that no matter how great the problems with sources for the period between 600 and 800, they are nothing compared to the difficulties of understanding the fifth and sixth centuries. In popular works those centuries are often referred to as ‘the dark ages’ and radically different interpretations have been produced about many key aspects of what may have occurred during that time.

One of the major distinguishing characteristics of the four peoples of Britain, as contemporaries acknowledged, was that they spoke different languages. The languages of the British, Picts and Irish were part of the Celtic group of languages, but fall into different sub-groups thereof. The British and Picts were both speakers of Brittonic, whose modern descendants are Welsh, Cornish and Breton. The Irish, on the other hand, were speakers of Gaelic, from which modern Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic descend. The two Celtic groupings are also known as p-Celtic and q-Celtic respectively because words that have an initial ‘p’ sound in Brittonic have an initial ‘q’ or ‘c’ sound in Gaelic; for example the cognate for Prydain, the medieval Welsh word for Britain, was Cruthin in Old Irish. Old English, the language of the Anglo-Saxons, belongs to a different language grouping, the Germanic, whose present day representatives include, in addition to modern English and German, Dutch and the Scandinavian languages. The Celtic and Germanic languages both belong to the same broader language grouping that is known as Indo-European.1

It might be expected that language difference would be emblematic of much broader cultural and organisational differences between these peoples, as contemporary writers appear to have believed, and some of these issues are explored further in Chapter 1. However, it should be made clear from the outset that the matter is not as straightforward as it might at first appear. To identify certain areas as British, Pictish, Irish or Anglo-Saxon is not to say that these were the only languages spoken in their territories, or that all the inhabitants within them were culturally homogenous and had had common histories. Rather what is identified through such labels are the language and culture of the dominant groups within the provinces who might themselves be of much more mongrel origins. The whole question of ethnic identities and the circumstances in which they might change are currently of great interest in early medieval studies, and will be borne in mind throughout this work.

Religion can be one of the ways through which cultural difference is expressed, and the preferences of ruling elites may dictate the nature of the dominant religion in areas under their control. In 600 the British were Christians, as were the Irish, both those living in Britain and those who had remained in their homelands. The Irish had been converted with the aid of British missionaries such as Patrick and through other contacts with areas of Britain, and so the term ‘Celtic church’ is sometimes applied to describe the common features of the British and Irish churches, though as the seventh century progressed greater divergence of practice was to be found, and many commentators feel that to use a common term can be misleading.2 In contrast, the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons and Picts to Christianity occurred somewhat later, beginning in the latter part of the sixth century, but gathering increasing momentum in the course of the seventh century. The date 597 would in fact be a more significant one for marking the start of this volume than 600, for that year saw both the death of Columba of Iona, who may have been the first to bring Christianity to the northern Picts, and the arrival in Kent of the mission despatched by Pope Gregory I and led by Augustine which had the express aim of effecting the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons.

Conversion and the Christianisation of the different peoples of Britain are therefore major topics within this book that also enable us to explore the workings of their political systems and the structures of their societies. As will emerge in Chapter 2, whose main topic is the conversion of Britain to Christianity, the decision whether to accept or reject Christianity or to support variant tendencies within the church could be a political one and the cooperation of rulers and the nobility was a prerequisite for establishing the structures that would allow a broader diffusion of Christianity within society. The process of the absorption of Christianity into the societies of early medieval Britain should enable us to study various aspects of them that are difficult to study by any other means. This is because whenever or wherever Christianity has been introduced it has always been adapted and affected, without fatal infringement of its basic tenets, to preexisting social norms and religious beliefs. The most superficial consideration of Christian communities around the world today reveals how varied they can be in the forms of their worship and expressions of belief even though all draw on the same set of scriptural authority preserved in the Bible and share basic tenets of the faith and their liturgical manifestations. Even in just one branch of the Christian church, for instance that of the Roman Catholics, there are substantial differences in ecclesiastical culture between churches in Central America, Africa and Europe.

With such key issues in mind, Chapter 3 will look at the structures and culture introduced by the church into Britain and Chapter 4 will attempt to assess the impact of the church on native lay societies. In setting out his aims for the series the General Editor has regretted the tendency in many general histories to isolate the topic of religion in its own separate sections and even to view it as marginal in order ‘to concentrate on matters which may seem more important to our increasingly secular-minded age’. It is the contention of this volume that such an approach would be completely inappropriate for the early Middle Ages. When the same families, and sometimes the same individuals, who provided the military and political muscle also com...