![]()

1

WRITING FOR THE BODY

Notation, reconstruction, and reinvention in dance

Abstract

This essay was commissioned for a musicology conference at the University of Chicago and is pitched at a nonspecialist audience. It is one of the few essays here that makes reference to my work in the early modern (see also Chapters 5 and 11). The question of dance notation as a writing for the body sets the stage for the issues surrounding dance and writing in the following three chapters where it is a matter of (1) critical interpretation faced with modernist aesthetics (Chapter 2), (2) the circulation of choreography in the public sphere as discourse (Chapter 3), and (3) the American critical reception of the theoretically informed work of William Forsythe (Chapter 4). These three chapters also develop the theme of dance and writing in the context of the criticism of the critics. In all of these cases, it is not only a question of dance in writing but also of dance as writing (a root sense of the term choreography). And it might also be noted that the interactions of dance and new media overlap perhaps more than we should like to admit with the theme of the archive in which notation participates as well as with the question of the score that is present in the phenomenon of danced reenactments as well as in new cognitive studies of dance. This theme also bleeds into Chapter 6 (“Figurae”) under the guise of drawing as writing. In this way, one can begin to see how the thematics of dance and writing also engage with the visual. I should note, finally, that Frédéric Pouillaude’s masterful chapter in Unworking Choreography on “Writing that Says Nothing” opens up new vistas in this conversation.

Choreography, from the etymological perspective and by virtue of current usage, seems to be a portmanteau word referring to two kinds of action: writing (graphie) and dancing (choros). As such, the word choreography seems to encode a theory of the relation of dance to scripturality – of writing as movement and dance as text.1 The theory seems to be that movement originates in the text through which it is initially thought and recorded. But an implication of the theory is that something called choreography remains in the wake of its performance. In other terms, choreography denotes both the score of a dance and the dance itself as perceived in real time and space – which raises the question: When we observe a dance, do we also observe (its) writing?2 That question could be rephrased to ask: What does it mean to “see” choreography? The writing I refer to as being “seen” is not necessarily synonymous with notation. But notation generally also conjures up the image of a dance in preparation or a dance remembered. The history of notation is thus related to that of publishing.3 But, possibly thanks to the modernist intertwining of dance and poetry, contemporary thought on dance is frequently split between a concept of dance-as-writing and a concept of dance as beyond the grasp of all language, especially written language.4 The trope of dance-as-writing assumes that one does not go to the theater only to see dancing but also to “read” something called choreography, which is “written” in time and space. There is an argument to be made that choreography exists as a visual component of the dance as it is being performed: the dance itself, independently of its actual performance, has an identity. The history of dance notation always reflects this complex relationship among dance, language, and writing, though the role of notation changes dynamically from the Renaissance through the twenty-first century and thus exerts a powerful influence on what we believe dance to be, and on how we experience it.

The Renaissance tablature in which letters represent named steps – the letters run along the edge of the musical staff to indicate how a step correlated with the music written for it – constituted the first attempt in the West at notation for courtly social dance. Early examples of tabulation are found in the Spanish Cervera manuscript (second half of the fifteenth century), which uses both letters and symbols, and the Burgundian Manuscrit dit des basses danses (c. 1523). The earliest published notation is in Michel de Toulouse’s dance manual, L’art et instruction de bien dancer, which appeared toward the end of the fifteenth century. In 1588 Thoinot Arbeau used the letter system along with verbal description in his dance treatise Orchesographie. Early modern notation of courtly social dance set a precedent for the representation of danced steps with linguistically based signs, which were frequently letters of the alphabet.5 The alphabetical sign was derived from the abbreviation of the step’s name: r for révérence, b for branle, and so forth. The sign also indicates that at least symbolic relations existed among choreography, natural language, and writing (printing) – relations reinforced by the appearance of notated dances in book form (the dance treatise or manual) toward the end of the sixteenth century. Like writing itself, notation was divorced from the expressive realities of what linguists call enunciation; that is, the act of producing sounds or movements in real time and space are separated from their essentially “oral” character. Treatises in which notation occurred are notorious for providing no insight into the physical dynamics and stylistic detail of movement. One important term for historical dance, fantasmata, is a notable exception.6 Found in Domenico da Piacenza’s early fifteenth-century treatise, fantasmata as a stylistic term is central to the performance of historical dance from the fifteenth to the seventeenth century. As a kinesthetically based term, however, fantasmata eludes notation.

More or less contemporaneously with the emergence of notation in the late Renaissance, geometrical or letter dances staged bodies as letters of the alphabet and other visual symbols. Geometrical dance, as a choreographic rather than a notational phenomenon, inverted the relationship between dance and text, making dance appear textual in its very performance. Choreography emulated the spatial presentation of written characters.7 The geometrical patterns had significance as letters forming words or as allegorical signs. Libretti for some court ballets with geometrical dances show the successive patterns of the dances, but without any indication of the movement that configures and evolves the patterns. The figures are noted on the page as configurations of dots marking the placement of each dancer. Hence aspects of early notation suggest that reading was intrinsic both to decoding a social dance and to watching theater dance. Dance history presents us with a complex weave of oral and choreographic culture.

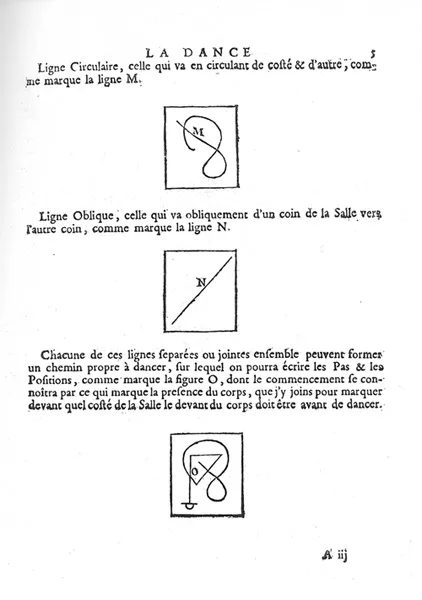

Baroque dance (also known as la belle danse), which developed chiefly in France during the seventeenth century, had a far more extended and intricate vocabulary than Renaissance dance. A new form of notation was invented for it by Raoul-Auger Feuillet, based on the work of choreographer Pierre Beauchamps, which appeared in print by 1700.8 As Sally Ness has observed: “Wherever codified gestural techniques have evolved, wherever habits of movement practice have stabilized enough to produce a continuity of movement style, general principles of conduct are operative in a performance discipline.”9 With the baroque, dance reached the status of a discipline in the Western tradition. Feuillet notation, which codified the step, the path of choreography through space, and its relationship to music, was much more comprehensive, and much more challenging to decode, than Renaissance tabulation. Although Feuillet notation is a track system rather than a word-based system, it shares grammatical aspects of language-based symbolization. Its very possibility suggests that baroque dance alphabetizes the body from the hip down into tropological relationships. Other aspects of writing infiltrate its denser grid: notably, the concept of floor pattern as the page and the concept of the body as a cipher on the page.10 The page itself becomes the floor one traverses in dancing, obliging the decoder to read not only in a linear but also in a diagrammatic manner. The sense of the floor as square and the typical symmetry of the patterns is easily encompassed by the page or the open book.11 These spatial relationships – the relations of the dance floor and the danced patterns upon it to notational script and the page – underlie the sense that baroque dance existed largely in relation to the conditions of possibility of its own notation.

In the case of baroque dance, we are confronted with the situation that Michel Foucault called the classical episteme, in which the representation of reality corresponds point for point with reality itself (Figure 1.1).12

FIGURE 1.1 A Page from Raoul Auger Feuillet’s Choréographie ou l’art de décrire la danse (Paris: 1700).

The end of the classical episteme of representation (in dance, in the eighteenth century, which corresponds in dance to the ballet d’action), introduces a disparity between action and the ways of representing action – a decline in what is knowable by humankind about its own activities. The reform of ballet d’action aims at a reduction of conventions surrounding dance vocabulary and a new emphasis on expression. Baroque dance, particularly in France, deployed a formal courtly and highly technical vocabulary that underwent significant transformations in the hands of ballet masters such as Gasparo Angiolini, Jean-Georges Noverre, and Jean Dauberval, becoming, over the course of the eighteenth century, “theater dance,” with an emphasis on emotional expression and narrative.13 Pierre Rameau and others proposed variants of Feuillet notation throughout the eighteenth century, also using images of the body; but this was the period of the gradual decline of court ballet as theater dance (except for opera). The form of dance that was in decline was of the same formal nature as the notation designed to preserve it. Ballet d’action, like glotto-genetic language theories of the eighteenth century, was interested in emotion as the genealogy of speech. No new system of notation arose to record the pantomimic innovations of ballet d’action, possibly because it subscribed to a concept of gesture as the primitive origin of language. Condillac, Rousseau, and Vico began the discussion in the eighteenth century of original language, in which gesture was thought to be at the basis of natural language and hence also of theatrical speech. The model for dance at this time was the voice rather than the text. One could say that the presence of the written sign in dance history up until this time was symbolic of a desire to reject the role of the voice in the production of movement.14 It would be a contradiction in terms to have prelinguistic gesture recorded in a sign system, when it is precisely the conventional theatrical and linguistic sign that this form of choreography puts into questio...