Introduction

In a metaphorical sense, the National Mall operates as a stage where Americans can perform their roles as citizens of the United States. They become literal actors in the public sphere when gathering on the Mall for peaceful assembly, whether it is to contemplate the nation’s history via the museums and artifacts collected there, or to protest the limits of American freedom through political rallies and other gatherings. In addition, the buildings, memorials, and monuments situated on the Mall behave as rhetorical actors that provide material reminders of our shared cultural history. The concrete elements of the Mall and its visitors are constantly engaged in an imaginary conversation over the appropriate interpretation of national values. As monuments concretize the values that citizens of the past believed should be upheld, present citizens reflect upon and reform these social values through new acts of protest, civic engagement, and monumentalism. This historical exchange has resulted in the design and construction of two commemorative sites in the new millennium that preserve the African American experience for future visitors. This case study outlines the role of racial politics in the creation of sculpture, architecture, and public space on the National Mall. I argue that the techniques artists employ to design commemorative spaces are not free of cultural meaning, but are inherently conditioned by the cultural traditions inherited from the past. These cultural histories limit the ways a designer can use form to interpret contemporary meaning, which, in turn, demand that an artist consciously manages the cultural implications of employing specific techniques.

The 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom is a premier example of the types of political rallies that have been staged on the National Mall. The postwar activities of leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., A. Philip Randolph, and Bayard Rustin clearly articulated the moral failures that racial discrimination represented for American democracy. However, in the 1950s, most of these protests took place within the American South where racial tensions were historically most intransigent. Once the strategy of peaceful protest gained momentum in the South, it was implemented at a broader scale. By the time it reached the Mall, its message had reached thousands of people; not only was it heard by the thousands of volunteers directly participating in these protests, but also it was seen and heard by tens of thousands viewing these events from their television screens, newspaper photographs, or those listening to radio programs announcing these problems to the world. During this march, the Mall operated once again as a stage for enacting a national conversation, this time about the inalienable rights of black Americans. In addition to speaking to the world, black volunteers made a plea to the nation to preserve the most enduring values of democracy. They stood in proximity to the statue of Abraham Lincoln situated in the Lincoln Memorial, and metaphorically spoke to George Washington in the form of the Washington Monument captured in many of the period’s photographs. In light of this, we cannot underestimate the power that black volunteers held at this moment. The high visibility of black bodies on the Mall exposed the conspicuous absence of visual representations of minorities in this symbolic space. Before 1960, representations of African Americans on the National Mall were visible but modest. As an example, Harper’s Magazine produced illustrations in the nineteenth century that depicted the black slaves leased by Southern plantation holders to construct the U.S. Capitol Building, and ornamental reliefs existed in small monuments depicting the agricultural products of Africa, or statues referencing freed slaves by the 1880s and 1890s.1

Within this artistic context, a concrete structure entirely dedicated to the African American experience is a major statement of inclusion within the National Mall. The first commemorative project of this nature was the Martin Luther King Jr. (MLK) Memorial, which began as a design competition in 2005 and opened to great fanfare in 2009. A second commemorative project, the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (SNMAAHC) also began as a design competition in 2009.

While almost everyone agrees on the value of preserving the African American experience for future generations, the form and content of this effort has provoked serious debate. The question of which artistic forms and materials are most appropriate for commemorating this past has proven a difficult question for the sculptors, architects, and urban planners involved. At least two distinctive artistic traditions have influenced the designs of the above-mentioned projects. The first is the Beaux-Arts traditions that dominated late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century federal construction during the period now called the “American Renaissance.”2 This approach was marked by a return to and revision of neo-classical European aesthetic traditions on American soil. The second artistic tradition was the rise of abstract modernism that emerged in the postwar period as legislators adopted a new official building style for federal construction. As architectural tastes changed, the symbolic purpose of the Mall also shifted; initially a space of respite and leisure, the Mall quickly became a symbolic core for the nation after the turn of the twentieth century. A brief examination of this history will provide some background into the forces that generally condition a designer’s choices when creating commemorative spaces for the Mall.

The Literal and Representational Functions of the National Mall

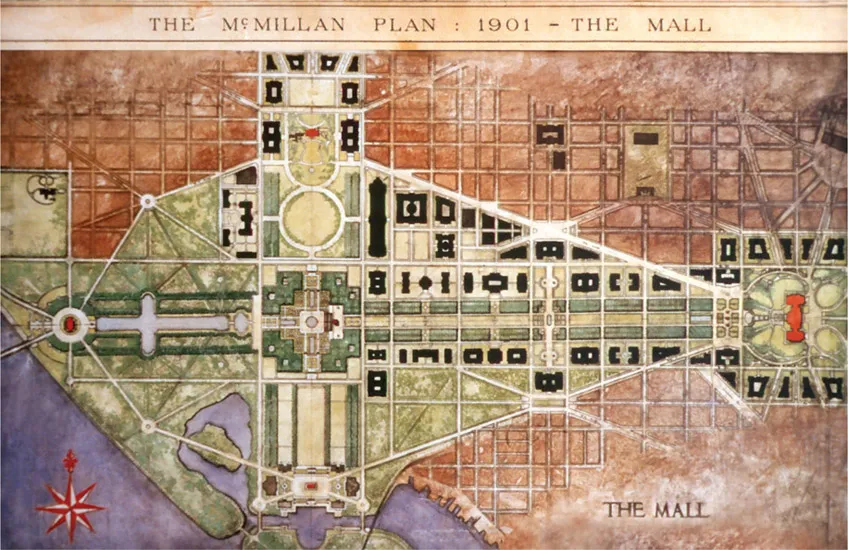

Figure 1.1 McMillan Commission Plan of the National Mall in Washington, D.C. (c.1901).

The National Mall currently is formed by an uninterrupted central axis that stretches across the heart of Washington, D.C. As an urban spatial form, the Mall is essentially a vast public lawn that stretches from the foot of the Capitol Building to the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. The Frenchman Pierre Charles L’Enfant was commissioned to design a public space for the Capitol in 1792, and his initial designs emulated French and British landscape conventions by providing a rambling pastoral escape from the bustling metropolis beyond. As a romantic landscape, the Mall was constantly in danger of being broken up to accommodate municipal functions that seemed more pressing for an ever-expanding capital. This pressure for change only increased as the aesthetic appreciation for pleasure gardens waned in the late nineteenth century. As early as 1816, the architect Benjamin Latrobe wanted to place a national university immediately across from the Washington Monument, which would have materialized one aspect of L’Enfant’s initial plan for the capital.3 In 1841, Robert Mills proposed to subdivide the Mall with major vehicular thoroughfares to provide access to and from satellite branches of the Smithsonian Museum. None of these changes ever took shape. Instead, a permanent public lawn was secured with the adoption of the 1901 McMillan Commission Plan. This plan employed a modern conception of urban space that geometrically balanced building masses and spatial voids in order to structure the viewer’s experience of the capital. In contrast to the restricted spaces that characterized less democratic regimes, the Mall allowed everyday people access to the most centralized and unifying space of the Capitol. In this sense, the people of the republic served as one of the decorative elements of the plan. By the end of the twentieth century, the physical integrity of the Mall remained intact even as new construction projects began.

The spatial organization of the McMillan Plan ties together buildings and spaces designed in many different styles, including the above-mentioned neo-classical and modernist styles. Traces of each artistic tradition can be found in the design of the MLK Memorial and the Smithsonian Museum of African American History and Culture, although one approach tends to dominate in each case. The project team for the MLK Memorial employs a monumental approach to space that incorporates a 30-foot statue of the slain civil rights leader. Within the context of the Mall, this heroic depiction of a black, male subject diversifies the racial and ethnic characters used to illustrate American life. The naturalism of Martin Luther King Jr.’s facial expression also becomes an explicit factor of the design. The mimetic, or imitative strategy used to capture his inner character, dates back to Beaux-Arts sculptural practices popularized in the nineteenth century. Artists trained in French academies learned to imitate the lines of natural forms, and, in the case of heroic subjects, they strived to emulate Greek and Roman ideals of beauty. Americans trained in these academies brought this style of sculpture back home to depict heroic national subjects. The mannered poses American sculptors applied to their artworks exaggerated the noble qualities of their subjects by emulating the virtuous characteristics of classical precedents while maintaining a realistic likeness of contemporary figures. This realism reflected the belief that human nature was an extension of organic nature, and universal laws of order served as the basis for artistic beauty.

In 1840, the American artist Horatio Greenough created a statue of George Washington that was patterned after the Greek god Zeus. While Washington’s physical stature and pose mimics the perpetual youth of its divine precedent, his head exposes the baldness of old age that exemplifies the wisdom required of a great leader. Another example of the Beaux-Arts style of representation is Daniel Chester French’s pensive statue of Abraham Lincoln, which is now the most famous aspect of the Lincoln Memorial. French’s depiction of Lincoln, loosely based from a life-cast of the president taken shortly after his death, emulates the repose of Greek and Roman statuary at a grand scale. Its solemnity reflects the sorrow and shame the country suffered after Lincoln’s assassination, and its scale reflects the grand ideals for which he gave his life in order to preserve a political union between abolitionist and slave-holding states. The importation of the Beaux-Arts style marked the growing maturity of American public taste, although some period architects objected to an over- reliance on European traditions in order to invent an American style.4 The design of heroic statues today can be interpreted as a revival of these historical practices, and the selection of minority subjects in these cases are an explicit attempt to situate nonwhite peoples within the Beaux-Arts artistic tradition. The statue of King elevates the physiognomic depiction of black subjects by reflecting mimetic ideals of beauty into the contemporary landscape. The heroic display of black figures was not always considered an appropriate subject for representing national history. Historical statuary in France was a category reserved for depicting national leaders and celebrated men, and most of these were of European descent. Charles Cordier was one of a few French sculptors to include heroic black figures in his artistic oeuvre, and this was in part predicated by a desire to visually represent the ethnographic variety contained within the French Empire. Cordier studied r...