![]()

PART I

![]()

CHAPTER 1

SUSAN FOURNIER

It has been ten years since the publication of “Consumers and their Brands: Developing Relationship Theory in Consumer Research” (Fournier 1998). Over the course of the decade, we have learned a great deal about the nature and functions of consumers’ relationships with brands, and the processes whereby they develop at the hands of consumers and marketers. In a broader sense, brand relationship research, grounded as it is in the notion of consumers as active meaning makers, helped pave way for the paradigm of co-creation embraced in brand marketing today (Allen, Fournier, and Miller 2008). Recent research, such as that in this volume, continues to build upon basic relationship fundamentals. Still, not surprisingly, many unresolved issues and conundrums remain. My own thinking about consumer-brand relationality has also evolved a great deal, particularly as important realities unanticipated or underdeveloped in the original theory are brought to the fore. In the sections that follow, I identify lessons I have learned about the relationships consumers form with their brands. These lessons are organized within the broader theoretical framework that guided my original thesis. Where applicable, I have leveraged research that my colleagues and I currently have in progress to inform my points.

TENET 1: PURPOSEFUL RELATIONSHIPS

| Tenet 1: | Relationships are purposive, involving at their core the provision of meanings to the persons who engage them. |

A core insight from my thesis research emphasizes the purposeful nature of consumer-brand relationships: brand relationships are meaning-laden resources engaged to help people live their lives. According to this tenet, the relationships formed between brand and consumer can be understood only by looking to the broader context of the consumer’s life to see exactly what the brand/company relationships serviced. Still, in conducting our research, we have been guilty of reifying brand relationships. We forget that relationships are merely facilitators, not ends in and of themselves. A strong relationship develops not by driving brand involvement, but by supporting people in living their lives.

Academics and managers alike fall into the trap of assuming that brand relationships are all about identity expression: that the driving need behind people’s brand relationships has to do with trying on the identities that the brand enables, or otherwise gaining status through the brand. This logic leads to a natural circumscription of the relationship phenomenon, wherein the perspective is meaningful only in high visibility/high involvement categories where identity risks apply. Brand relationships can serve higher-order identity goals, addressing deeply rooted dialectic identity themes and enabling centrally held life projects and tasks. But they can also address functions lower on the need hierarchy by delivering against very pragmatic current concerns. Karen, our struggling single mother from the original thesis and article, bought Tide, All, and Cheer because one of these reliable mass brands was guaranteed to be on sale when she needed it. Karen’s brand portfolio was filled with habitual purchases of otherwise “invisible brands” (Chang Coupland 2005). These relationships allowed Karen to extend her resources and develop the skills and solutions she needed to make it through her day. Karen’s basic commercial exchanges can still be understood as brand relationships. Less emotional, surely, and less salient, perhaps; but brand relationships they remain.

Many brand relationships are also functional in that they focus on extracting greater exchange value from the company and the brand. So-called loyal customers often engage relationships not through zealous brand evangelism, but rather through a pragmatic desire for the better deals and special treatments that come with elite relationship status. Here again strong brand relationships emerge as a by-product of meeting functional needs, not a drive to express identity through the brand.

The status of the brand relationship as a means versus an end is nowhere clearer than it is within the context of brand relationships forged at the community level. As seven years of brand community research has taught us, people are often more interested in the social links that come from brand relationships than they are in the brands that allow those links to form (Cova and Cova 2002; see also Chapter 9). People often develop brand relationships to gain new social connections or to level out their connections in some significant way. Brand relationships can also provide venues wherein emotional support, advice, companionship, and camaraderie are provided. As research into so-called Third Place brands (Rosenbaum et al. 2007) has pointed out, these strong brand relationships are a consequence, not a cause; they result from the social connections engendered through the brand relationship. As researchers, we are guilty not just of prioritizing identity needs over those that are more functional, we have also disproportionately focused on idiosyncratic relationships versus collective relationships supporting the brand.

Robust brand relationships are built not on the backs of brands, but on a nuanced understanding of people and their needs, both practical and emotional. The reality is that people have many relational needs in their lives, and effective relationships cast a wide net of support. Table 1.1 provides a sample of the different purposes that brand relationships can serve; in Chapter 5, Ashworth, Dacin, and Thomson provide another perspective on the functions served by people’s relationships with their brands. Brand relationship efforts that comprehensively recognize and fulfill the needs of real people—individually and collectively—are those that deliver results.

Solving the “reification problem” also requires qualifying the conditions wherein brand relationships will viably form. When we push the theory too far and imply that all consumers form relationships to the same degree and in all circumstances, we unnecessarily lose supporters. Several researchers have turned to attachment theory and its secure, anxious/ambivalent, and avoidant relationship styles for person moderators of relationship activity (see Chapter 19). In our own research, we have developed an attachment construct specific to commercial relationships that holds promise in predicting brand relationship propensities (Paulssen and Fournier 2008). Consumer manifestations of different relationship styles (independent, discerning, and acquisitive, Matthews 1986), orientations (power versus intimacy, McAdams 1984), and drives (McAdams 1988) should also inform the boundary conditions affecting people’s relationships with brands.

Table 1.1

A Sampling of Relational Needs and Provisions | Reach beyond my network | Raise the quality of my interactions |

| Establish roots | Pursue luxuries guilt-free |

| Preserve moments of privacy | Sustain my passions |

| Capture the present | Explore different parts of my identity |

| Get help to get stuff done | Express devotion |

| Cultivate interests and skills | Deepen bonds through shared ownership |

| Stay adventurous | Aspire to be my own keeper |

| Manage expectations of me | Help position myself in the larger picture |

| Support my unique DNA | Level out my connections |

| Help resolve nagging tensions about who I am | Distance me from an unwanted self |

| Enable important role transitions | Provide comfort through routines and rituals |

| Help me contribute to the “greater good” | Get special treatment from the company |

| Build legitimacy and overcome fear of stigma | Get more out of my brand investments |

| Relax within a safe haven | Get technical support and advice |

| Get emotional support and encouragement | Clarify my values |

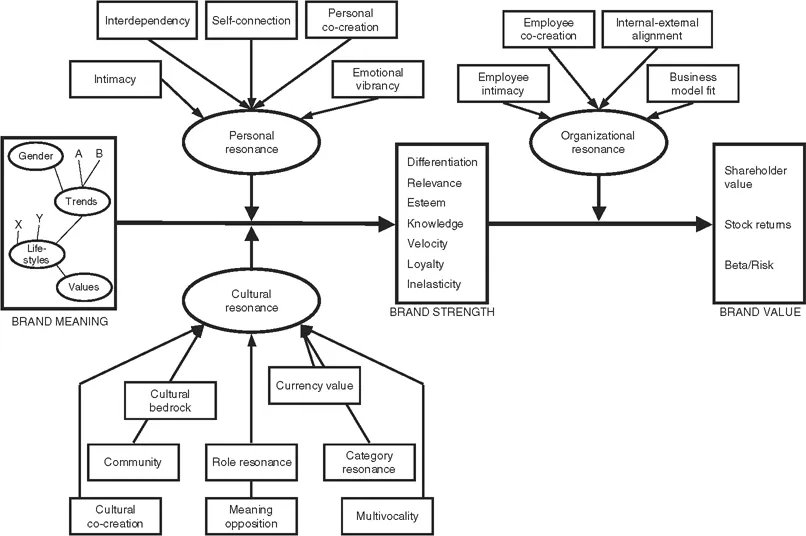

To control runaway applications, we also need a way to identify the relationship potential of a given brand. Category involvement serves this purpose for some, but the concept is not consumer-sensitive. Much has also been written about the facility offered through brand anthropomorphization. This factor has proven itself a red herring, or a moot point in the simplest case. We do not need to qualify the “human” quality of the brand character as a means of identifying the brand’s relationship potential: all brands—anthropomorphized or not—“act” through the device of marketing mix decisions, which allow relationship inferences to form (Aaker, Fournier, and Brasel 2004; Aggarwal 2004). More useful are screening criteria that build not from product categories and brand characteristics, but from the contexts of people’s lives. One such approach builds upon the insight that consumers play active roles as meaning makers in their brand relationships, mutating and adapting the marketers’ brand meanings to fit their life projects, concerns, and tasks. The key is to understand how meanings attain significance in the context of the person’s lifeworld. In current research (Fournier, Solomon, and Englis 2008), we have come to understand this question as a search for “Meanings that Matter,” the answer to which lies in the construct of brand meaning resonance. Figure 1.1 provides a multifaceted model for thinking about the resonance construct and its role as a relationship strength mediator. Resonance forces a shift in our thinking from firm- and competition-centric criteria such as the salience, uniqueness, favorability, and dominance of brand meanings to the reverberation and significance of those meanings in the personal and sociocultural world. Resonance focuses not on what brands mean, but rather how they come to mean something to the consumers who use them. It highlights the developmental mechanisms driving the initiation and maintenance of consumers’ relationships with brands.

Figure 1.1 Resonance: How Meanings Matter

Holt (2004) and others (Chapter 9; Schroeder and Salzer-Mörling 2005; Thompson, Rindfleisch, and Arsel 2006, to name but a few) have contributed greatly to our understanding of the cultural processes that enable brand resonance. This research serves a critical perspective-gaining function by shifting attention from consumers’ relationships with brands to brands’ relationships with cultures. Predictable psychosocial factors can also trigger relational activity by precipitating a search for resonant brand meanings (Fournier 1998; see also Chapter 9). Events such as coming of age, the transition to parenthood, or a change in marital status serve as se...