![]()

Chapter 1

Relational and developmental trauma

The impact of complex trauma on children’s sense of selves, relationships, and development

Introduction

This chapter will first explore within the context of relational and developmental trauma the types of traumas and losses which children have experienced, as well as the interplaying factors which need to be considered. This will be followed by discussing the differences between a Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) framework, and a relational and developmental trauma one; and subsequently the terms “relational trauma” and “developmental trauma” will be expanded on, followed by reflections on some of their wider implications. Case examples, reflective exercises, and metaphors will be interwoven throughout. This chapter sets the scene for the subsequent chapters, which will be centred around the impact of relational and developmental trauma on children’s bodies, brains, attachments/relationships, emotions, senses, identity, behaviours, and cognitions. In later chapters, these areas will be applied to some specialist subgroups and contexts within this population such as when working with unaccompanied asylum-seeking young people who offend, or when intervening with children who have experienced relational and developmental trauma within settings such as schools and residential homes.

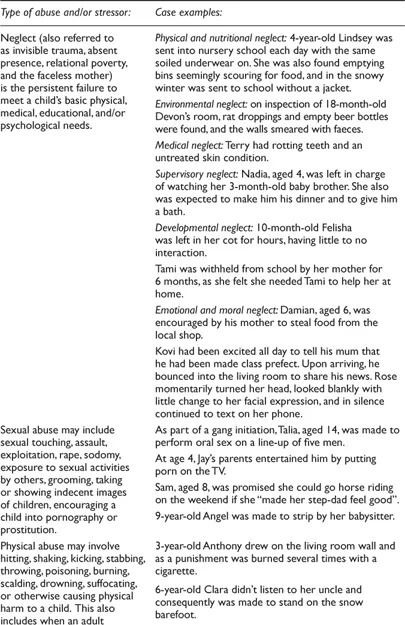

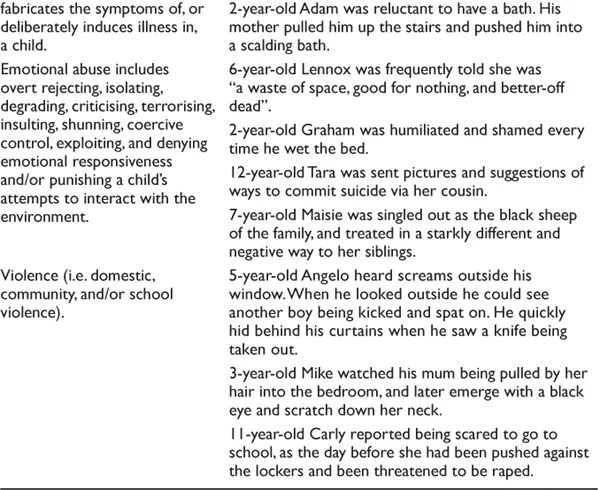

Children who have experienced relational and developmental trauma often have lived through a matrix of multiple, overlapping, and co-occurring traumas, losses, and stressors (Table 1.1 offers some examples of relational and developmental trauma). Within the literature, these experiences are often referred to as chronic, cumulative, and/or multiple traumas. In many cases, these traumas and/or disrupted attachments have begun during the vitally important in-utero period. Although traumas can take place within intra-familial, extra-familial, institutional, or street-stranger contexts/relationships, this book holds a firmer focus on the intra and extra-familial experiences.

Interplaying factors

Before going on to discuss what relational and developmental trauma is, and what some of the implications of these experiences are, we need to be mindful that these children are a heterogeneous group of unique individuals, and that trauma does not occur within a vacuum; it is influenced by multiple systemic, relational, and contextual elements. Therefore, the impact and consequences of the traumas listed in Table 1.1 are likely to be on a continuum, and shaped by a number of interplaying factors including:

Table 1.1 Types of relational and developmental trauma experiences

1 The child’s temperament and unique attributes, including biological and genetic factors

2 Previous life events and stressors

3 The severity and nature of the traumas

4 The frequency and duration of the traumas

5 The relationship with the person who carried out the abuse

6 The response of others around the abuse e.g. how it was managed and whether it was believed/validated

7 The sense-meaning-making and attributions made about the traumas

8 The age and stage of the developing child

9 The presence and/or absence of protective factors

10 The cultural and contextual relevance of the traumas

These variables are crucial in further understanding, assessing, and intervening with this client group. Additionally, the majority of relational and developmental trauma experiences tend to involve interwoven types of abuse, which can make clear differentiation challenging. For example, it is uncommon for physical abuse to occur without some form of emotional abuse. Furthermore, the extent and nature of relational trauma is not always clear cut or simple to disentangle, as the child would have experienced a range of relationships, both through being exposed to an extended network of adults, and/or through the varying parenting styles of their primary caregivers.

These trauma experiences have generally occurred whilst the child is still developing, has a weakly formed cognitive framework, and is often preverbal. Moreover, these experiences are often characterised by a lack of the fundamental relational protective shield which children need, and instead the trauma may occur at the hands of the very person who is supposed to offer them comfort and safety. The experiences described in Table 1.1 are beneficially considered within a multilayered lens of attachment and trauma, whilst taking into account the wider context which may include:

1 The potential difficulties of having a parent with mental health difficulties, a learning disability diagnosis, and/or using substances.

2 The type of milieu, family scripts, emotional world, and parenting models the child has been shaped in.

3 The intergenerational transmission of trauma and attachment styles; including unresolved trauma and “ghosts of the past” (Fraiberg et al., 1975).

4 The environmental, socio-political, and economic context.

Some of these complexities are captured in the following case:

Post the Rwandan Genocide, June had been raised in an institution. She had experienced multiple childhood traumas and losses. In her late teens, June began experiencing hallucinations and delusions, and shortly after arriving in the UK, she was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia and PTSD. June was homeless and drinking significant amounts of alcohol when she became pregnant with Sienna. Sienna’s father was in prison for assault and robbery. When well, June was able to offer a level of responsive, playful, and sensitive parenting to Sienna. However, when unwell, the situation significantly differed. The cramped household was chaotic and heaving with items ranging from newspaper cut-outs, to medication lying around, whilst the fridge remained empty, and the electricity unpaid. At these times, June struggled to move out of her own mind, and was preoccupied by intrusive thoughts and images. She expressed few positive emotions and interactions towards Sienna, and presented with a short fuse. For example, she regularly misread social situations and attributed hostility in others’ faces and actions. There was one occasion where June was arrested in front of Sienna for shouting racial abuse at their neighbours, and another when she was observed labelling Sienna a “dirty slut” and attributing her wetting to being purposeful and a plot against her.

Box 1.1 uses the metaphors of shark-infested waters and desolate islands to bring to life the lived experience of abuse and neglect as described in Table 1.1. See Figures 1.1 and 1.2.

1.1 Reflective exercises: metaphors of relational and developmental trauma Two metaphors which resonate for me when thinking about relational and developmental trauma and loss are shark-infested waters (e.g. abuse/frightening parenting) and desolate islands (e.g. neglect/relational poverty). The following build on these concepts, however it is acknowledged that metaphors fit differently with different people. If these don’t work for you, can you think of others that do?

Shark-infested waters:

Imagine swimming or being on the edge of shark-infested waters. Put yourself in the shoes of a child who is surrounded, trapped, and powerless by these big, fast, and unpredictable sharks. Waiting, anticipating, expecting and/or fearing being attacked. Feeling frightened, under threat, outnumbered, and on edge. Visualise each brush of seaweed, lurking shadow, or ripple in the water sending your body and mind into overdrive.

When in shark-infested waters what do you/can you do? a) swim away, b) punch the shark or wrestle it, c) stay incredibly still, or d) pretend to be a feared shark yourself? What if you don’t have the physical strength or knowledge to know how to fight or swim away from the sharks?

How would it change your responses and meaning-making if the sharks were sometimes friendly or even turned out to be dolphins? What would it be like to be taken out of the shark-infested waters and subsequently put in a swimming pool (e.g. foster care)? What if you were then returned to the shark-infested waters? What would be your source of comfort, anchor, or lifeboat?

Desolate island:

Some children who experience neglect and relational poverty might feel like they are stuck or stranded on a lonely, dry, empty, and desolate island. A place where one feels disconnected, disengaged, and invisible. The lack of water and nourishment can be likened to being starved of relational riches and interpersonal treasures. Neglect, although often sidelined compared to physical or sexual abuse, should be forefronted due to its powerful far-reaching impact on developing children.

What would you do to survive on a desolate island? How long would you look for hidden treasures or buried food? How would you learn new skills without people teaching or encouraging you on your journey? What might it be like to go from a desolate island into shark-infested waters, and back again? What might it feel like if your island was suddenly re-inhabited with new people, or through an arduous journey, you are taken to a more populated island?

The labyrinth of the care system

Another layer of complexity is for those children who have been removed and placed in the foster care system. Although they may experience a plethora of positive changes, for some, their waters may still look and feel shark-infested; and new lurking shadows, tides, and sharks may have appeared. For these children, their points of reference and anchors are no longer visible, and the new waters may feel and be unfamiliar. Similarly, once a child’s desolate island is re-habitated with new people, or through an arduous journey they are taken to a more populated island; this too can feel alien, hostile, and overwhelming. These children are placed amongst the complex labyrinth of the care system with new dilemmas, blind spots, turns, and twists to navigate – often under a wave of uncertainty and disorientation. “Why can’t I go home?”, “What is a ‘forever’ family?”, “What will I eat?”, “Can I take my dog?”, “Is it because I was naughty?”, “Is this because I told my teacher what daddy did?”, “How will my mummy know I’m ok and who will look after her?”, “What about school?”

Stacking-up on the experiences described in Table 1.1, these children also need to contend with a range of additional issues around social care and multiple professional involvement, family contact arrangements, potentially being separated from their siblings, and the widespread stigma of being in care.

These children may also experience multiple placement/school moves. Studies on placement instability and disruptions have shown that there are increased links with low self-esteem, poor self-worth, low mood, and behavioural, social, and emotional difficulties. Moreover, these children have limited opportunities for forming secure attachments to their carers, or long-lasting meaningful relationships (Leathers, 2006; Eggertsen, 2008). Most likely they also missed out on key early opportunities to learn, and be curious about themselves, which can further contribute to having an incoherent life narrative and a fragmented sense of identity and belonging. Illustrative examples follow:

Cindy shared how she had gone to school and unbeknown to her, her carer had given an unplanned notice. On arrival “home”, her social worker was waiting for her. Her belongings had been hurriedly packed in black bags.

Khloe was adopted with her younger sister and placed in her “forever family”. However, a few months later the placement broke down, and Khloe was placed back into foster care, whilst her sister stayed with the adoptive mother. She subsequently experienced seven placement moves, with the system designed to protect children like Khloe being responsible for new abuses. With each move, Khloe’s sense of safety was squashed, her defences reinforced, and her trauma jacket more firmly buttoned-up. With each transition, Khloe was faced with multiple emotional, relational, physical, and symbolic losses; ranging from losing material cherished possessions, to meaningful relationships, to her sense of familiarity. Khloe likened herself to “rubbish which needed to be disposed of”. See Box 1.2 for further reflection on placement moves.

1.2 Practical activity and reflection: moving placements 1 Put yourself in a child’s shoes when moving to a new “home” with new “parents” where everything is different and unfamiliar – from the smells, tastes, “language”, sounds, to rules, parenting styles, people, school, and surroundings. Children have to navigate these new environments from scratch, whilst often looking at themselves, others, and the world through a relational and developmental trauma prism (shark-infested waters and desolate islands). They generally make these moves on their own, without their relational anchor. What might that feel like? What impact might this have on your life narrative, sense of belonging, identity, beliefs, and expectations? What do the words “home” and “mother/father” mean to you? (Write a list or visually represent this i.e. with a collage.)

2 Building on bri...