![]() PART 1 Context

PART 1 Context![]()

CHAPTER 1 The Organizational Context

‘We cannot meet 21st Century challenges with a 20th Century bureaucracy’. Barack Obama, Nomination Acceptance Speech, 28 August 2008

This book covers a wide range of issues relating to information management in the context of organizations. Having some understanding of what comprises an ‘organization’ places anyone in a better position to deal with change, whether as the initiator of change or the recipient of the outcomes. Without this knowledge, inferior managerial decisions may result and staff may be poorly placed to adapt to new situations. This chapter deals with some of the broader issues that need to be considered to help ensure that innovation enables rather than disables improvement.

1.1 What Constitutes an Organization?

At its simplest, an organization is a group of people working together. It may range in complexity from ad-hoc local community groups to businesses, governments and international bodies. Each will have – to varying degrees – objectives, rules and structures. They may produce goods or services, or generate other outcomes as in the case of legal institutions, trade unions or religious bodies. They will aim to employ resources effectively and efficiently and need to operate within the law.

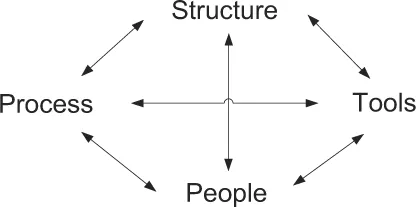

Detailed consideration of organization theory is outside the scope of this book; for further information see Handy (1993) and Crowther and Green (2004). However, there is merit in viewing an organization as a dynamic human system consisting of four basic elements (Leavitt et al., 1973).

Figure 1.1 Organizational model

• processes (Leavitt referred to ‘Tasks’ here):

– the organization builds or designs things or provides services by undertaking an organized assembly of activities that transform inputs into outputs, subject to particular controls

• structure:

– the organization has some broad, more or less permanent framework; some arrangement of processes and material resources and people in some sequence and hierarchy

• tools:

– the organization utilizes technological advances and provides tools that enable people or machines to perform tasks and to effect administrative control

• people:

– the organization is populated by, as Leavitt expressed it ‘these sometimes troublesome, but highly flexible doers of work’.

These elements serve as organizational levers of change and are interdependent in that any change in one will affect the others. Thus the introduction of a content management system will change the way people work, outsourcing tasks will change the structure and staffing elements and introducing a new product or service will require changes or additions to existing processes.

While other elements will be considered in more detail in later chapters, the structural aspect of organizations merits attention here.

1.2 Organizational Structures

When planning improvements in managing information, consideration needs to be given to the organizational context of the intended target area and to answering the following types of question:

• is the venture to be undertaken on an organization-wide scale, or departmentally?

• where are the decision makers located in the management structure?

• what professional and specialists need to be involved and where are they located?

To address these questions it helps to understand the type of management structures that exist in the organization.

As noted (Handy 1993), structure includes the allocation of formal responsibilities as depicted in the typical organization chart. It also covers the linking mechanisms between the roles i.e. the coordinating structures of the organization, if any are needed. Organizations change their design as they grow, based on what they would like to be – their mission and objectives.

Where a range of different products is produced or the enterprise operates over a large geographical area, the management structure will usually decentralize into divisions, each with its own supporting functions such as sales and marketing.

New organizations, especially entrepreneurial ones, tend to be heavily centralized, informal and lacking in bureaucracy with a flat structure. As they grow they need to introduce a certain degree of standardization and official routine as exemplified by a functionally structured hierarchy. Such bureaucracy is prevalent in most government organizations.

Information-intensive organizations such as those concerned with information technology or pharmaceutical research require approaches to management that differ from the traditional style of ‘command and control’ arising from manufacturing industries. Staff are highly educated, work will be less structured and emphasis is placed on teamwork and collaboration.

Matrix organizations are an example of a task structure which is job or project oriented. Personnel are grouped by product and function with the aim of gaining the benefits of both approaches. Thus a project manager has responsibility for a project, while a functional manager provides the necessary resources. The degree to which one manager has greater authority over the other can vary depending on the organizational culture, aims and objectives, for example.

1.3 Why Organizations Exist

An organization is formed, or comes about, for a purpose. That purpose may or may not be well defined, indeed, it may sit there as an aspiration with little to enable it to come into being. Visions and objectives are promulgated, but will have little relevance if there is no means to determine whether they have been achieved.

As organizations grow, the need for clarity of shared objectives becomes greater. For example, the records manager’s concern with managing emails is far removed from the worries of the transport manager about enlarging the lorry fleet to meet demand. However, the catering department’s desire to source ingredients locally may conflict with finance’s aim to reduce costs.

There are also differences in purpose between profit-making and government and not-for-profit agencies. While the former may place good financial performance as the prime objective, public sector organizations will place greater emphasis on the customer perspective.

1.4 What Organizations Do

In order to operate, an organization has a range of functions; that is, sets of related activities. ‘Functions’ are not to be equated with organizational structures such as the ‘finance department’, ‘personnel department’ or ‘production section’, as is discussed further below. While functions generally remain unchanged, managerial structures are less stable and may centralize, decentralize, devolve or otherwise restructure over time.

There are two types of function – operational and support – and it is important to know the distinction between the two.

OPERATIONAL FUNCTIONS

Every organization will have core functions that establish its identity and the reasons for its existence and thereby differentiate it from organizations in other fields of activity. Thus for a vehicle manufacturer, design and production functions are important, exploration is key for an oil company and providing sheltered housing is the focus of a housing association. These are referred to as ‘operational functions’.

SUPPORT FUNCTIONS

An enterprise cannot survive with operational functions alone. It has to exist within legal, regulatory, commercial and social environments which require it to have a range of other functions to support its day-to-day activities and longer term objectives. These are ‘support functions’ that are common to most organizations and provide the underlying support; for example, managing staff and finance.

As will be seen later in Chapter 5 relating to business classifications, it is important to understand the difference between these types of function. Consider the United Kingdom’s economics and finance ministry, ‘The Treasury’. It is responsible for developing and executing the British government’s public finance and economic policies. This ‘financial’ activity is an ‘operational’ function as it embodies the reason for the organization’s existence. However, The Treasury also has to manage its internal finance, such as expenditure on office supplies, repairs, salaries, and so on. This ‘financial’ activity is a ‘support’ function, vital for supporting day-to-day operations, but not one that will be core to driving the economic strategy of the country.

While functions will remain relatively unchanged as compared with managerial structures, there will be exceptions, particularly for operational functions. For example, Nokia was originally involved in wood pulp and paper manufacture and changed direction radically, moving into electronics. This will have required the introduction of new operational functions relating to the design and production of mobile phones. Nevertheless, Nokia will have continued to rely on its existing support functions before, during and after the change in strategy.

BUSINESS PROCESSES

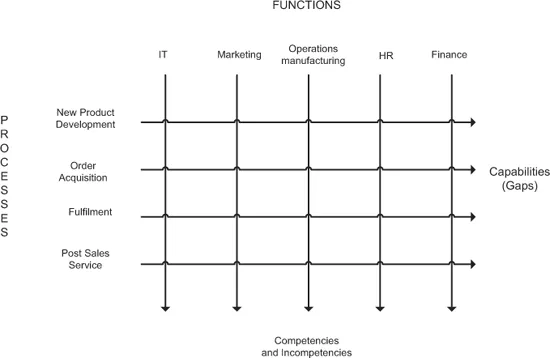

A function is defined as a set of related activities and does not in itself deliver a specific output. This is achieved by a business process which is a set of one or more linked procedures or activities which collectively realize a business objective or policy goal. Processes will cross functions to deliver the required output as exemplified in Figure 1.2 – based on Hatten & Rosenthal (1999).

Here five generic business functions (technology, marketing, operations, human resources and finance) and four principal customer-focused business processes (new product development, order acquisition, order fulfilment and post sales service) are identified. It provides a framework for the first step in an enterprise audit.

Capabilities are measures of the performance of business processes. Competencies are measures of the organization’s potential to conduct business at state-of-the-art level. Capability gaps are the inability to do things, and incompetencies are gaps in know-how. Detailed examination of these interfaces allows alignment and misalignment of functional competencies and process capabilities to be identified.

Figure 1.2 Aligning processes to functions

Source: Reproduced with permission of Elsevier

To complete the first step, one determines which of the various functions makes the largest contribution to the success of each business process. In Figure 1.2, each node or nodes (intersecting points) between processes and functions should prompt the questions: ‘is this particular interaction of function with process important to the performance of the enterprise’? and ‘if so, how and why?

1.5 Strategic Planning

The development of a strategy should progress according to some form of planning process. This process can be divided into the following stages:

• strategic analysis

• strategic choice

• strategic implementation.

Together they form a three-stage hierarchy as depicted in Figure 1.3 with the lower levels defining ‘how’ the preceding levels are achieved and the preceding levels defining ‘why’ the following activitie...