eBook - ePub

Adaptive Architecture

Changing Parameters and Practice

Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Andrea E. Hardy, Jacob J. Wilhelm, Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Andrea E. Hardy, Jacob J. Wilhelm

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 296 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Adaptive Architecture

Changing Parameters and Practice

Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Andrea E. Hardy, Jacob J. Wilhelm, Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Andrea E. Hardy, Jacob J. Wilhelm

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

The constant in architecture's evolution is change. Adaptive Architecture explores structures, or environments that accommodate multiple functions at the same time, sequentially, or at periodically recurring events. It demonstrates how changing technological, economic, ecological and social conditions have altered the playing field for architecture from the design of single purpose structures to the design of interacting systems of synergistically interdependent, distributed buildings. Including contributors from the US, UK, Japan, Australia, Germany and South Africa, the essays are woven into a five-part framework which provides a broad and unique treatment of this important and timely issue.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Adaptive Architecture è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Adaptive Architecture di Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Andrea E. Hardy, Jacob J. Wilhelm, Wolfgang F. E. Preiser, Andrea E. Hardy, Jacob J. Wilhelm in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a Architecture e Architecture General. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

Part I

Introduction

Introduction

I.1 Synopsis

Adaptive architecture can accommodate multiple purposes at the same time, sequentially, or at periodically recurring events. While most buildings—and the structures, materials, and environments that comprise them—have adaptable qualities, adaptive architecture has emerged as an important issue because of changing technology and economic dislocations that have drastically altered the field. For example, look at the impact of Uber (Barbaro and Parker, 2015). A globally successful car-sharing company, Uber allows individuals to use their personal vehicles as taxi cabs and to communicate with potential clients needing transportation through innovative applications downloaded to one’s smartphone. This same evolution of a “sharing economy” has changed architecture from the conceptualizing, designing, and constructing of buildings to the creating of interacting, synergistically interdependent, distributed systems, fueled by the invention and global use of the Internet. WeWork, provider of shared office space for small companies and technology start-ups, earned a market valuation of ten billion dollars after only six months since its first offering. This phenomenon affects retail merchandising and urban infrastructure as much as the design and construction of architecture. The chapters that follow explore such new and interacting systems, showcased through case studies that identify and investigate the variety of ways that adaptability influences architecture today, and how they may continue to revolutionize this field in the future.

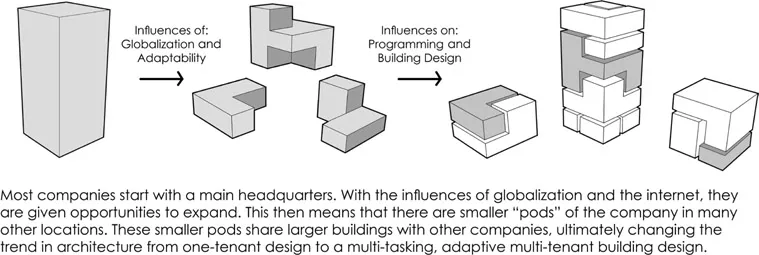

This book also explores the transformation happening in architectural practice as a result of the digital revolution, which has changed the world dramatically in the last several decades. Because of digital technology, practitioners must be aware and knowledgeable about a variety of innovative topics, and be able to accomplish many more tasks within ever shorter timeframes. As described in “Déjà vu” by Michael Totty (2002), the developments of the printing press, telegraph, radio, railway, airplanes, and the Internet historically made it easier for professionals, academics, designers, and people in general to share ideas and conceive new ones rapidly. While all of these inventions greatly influenced communication among people, with each step in technology there is an implicit expectation that we obtain more information, interpret it, and then put it to use for the benefit of society at large: an adaptability of knowledge and communication (Totty, 2002). Through the development of digital technology and the global economy, companies can now quickly share documents and information over long distances, allowing organizations to divide major headquarters into smaller segmented entities of the business in locations around the world (Figure I.1). Not only does this allow businesses to extend their global reach, but it also creates a new architecture of shared spaces, which can lead to collaboration among industries. This book has, as its main premise, flexibility at numerous levels, highlighted by the concepts and execution of the case studies that follow.

Figure I.1Influences of globalization and adaptability in commercial building design.

Source: Jacob J. Wilhelm.

I.2 Historical development of adaptive architecture

Change remains the only constant in the evolution of architecture. Hence, this book examines architecture as it has changed from utilitarian edifices serving basic community needs like fortifications for defense, aqueducts for water supply, harbors, roadways, and other hubs of transportation, all the way to today’s highly fragmented and specialized creation of spaces for living, working, producing, and conducting commercial activities, which are reflected in the popular phrase “Live. Work. Play” now used by many developers and designers. The book will also address facilities for schooling and education, healthcare, public services, recreation and entertainment, as well as other building types.

Such fragmented spaces continue to shape our culture and, in turn, our culture affects the design of our built spaces. The iterative influences between culture and architecture would not be possible without studies and analysis on functionality and habitability. Through the exploration of post-occupancy evaluations (POEs), building performance evaluations (BPEs), as well as research on “habitability,” designers are able to push the envelope of architecture forward by learning what buildings need and envisioning how they can adapt.

I.2.1 Functionality of adaptive architecture and flexible spaces

As a sub-discipline of architecture, a systematic approach to architectural programming originated in the 1950s, with POEs pioneered in the mid-1960s and universal design as a movement taking off in the mid-1980s. All of these subfields are concerned with the quality of the built environment as the end users experience it, and thus, they help us understand the functionality and habitability of adaptive spaces.

With constantly changing technology and with spaces increasingly programmed for multiple functions, it is becoming important to evaluate the levels of performance of buildings: their health and safety, their functional and task performance, as well as their level of social and psychological comfort and cultural satisfaction (Preiser and Hardy, 2015). By conducting research, observations, and interviews of these performance levels, we can assess the usefulness, habitability, and need for multi-functional, multi-tasking, and adaptive spaces. Through the evaluation of a building’s actual uses, we can begin to understand the habitability of its spaces.

I.2.2 Habitability and adaptive architecture

The emergence of the design and behavior field dates back to the mid-1960s. Variously referred to as environmental psychology, architectural psychology, ecological psychology, socio-physical technology, person–environment relations, man–environment relations, and human factors, its name depends upon which discipline or agency originates and sponsors it. We use the name “design and behavior field” to signify its relevance and utility to architecture and planning, and to a lesser degree to the social sciences.

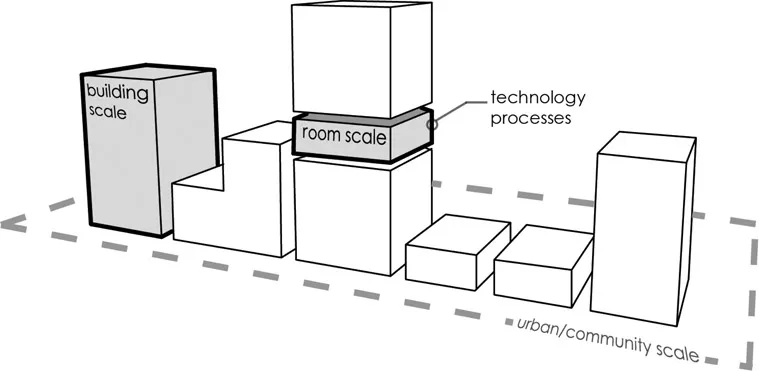

Elements of the design and behavior field, or what some call the “Habitability Paradigm” (see the Appendix), include buildings/settings, occupants, and occupant needs. It deals with the physical environment on a setting-by-setting basis, and builds up in scale from the immediate or proximate environment of people. Each higher order scale of the environment is comprised of units at lower scales, leading to the following hierarchy:

- region—an assembly of communities at the geographic scale;

- community—an assembly of city blocks or neighborhoods;

- facility—a complex of buildings such as a military base or campus;.

- building—an assembly of rooms or spaces;

- room—an assembly of workstations or activity/behavior settings;

- activity setting—the proximate environment in which behavior occurs, e.g., a workstation.

Adaptive Architecture covers not only the process of creating built environments but also the majority of the scales listed above. The past, present, and future habitability of a project directly relates to its adaptive capability, and the Appendix provides further insight into the theory and evolution of the “Habitability Paradigm.”

Habitability also relates to the many guidelines and code requirements that influence how the architecture profession responds to the continuously developing design and behavior field. Code requirements that reflect and enforce the American Disabilities Act (ADA), for example, have led to Universal Design, which transcends the ADA in spirit. The current trend toward adaptive public and private spaces shows the need to relate people to their surrounding spaces on one hand, and through universal design, to make products, buildings, transportation systems, and information technology accessible to all people on the other. Universal design follows the democratic principle of equality for all, regardless of disabilities, ethnicity, or culture (Preiser and Ostroff, 2001; Preiser and Smith, 2011). While information generated by the design and behavior field needs to become more easily accessible to and usable by architects, it is hoped that the applications of behavioral science in architecture and environmental design will continue to improve the quality of our everyday environment in the long run.

Figure I.2Scales of adaptivity.

Source: Jacob J. Wilhelm

The design and behavior field emphasizes the interrelationships, rather than cause–effect relationships, among environmental influences and people, which rules out architectural determinism. Like any other living species, humans seek equilibrium with a dynamic, ever changing environment, and through the use of analogies—such as living systems, organisms, and living species—we can more easily relate to and better understand the world around us. “[Analogies] make complicated things easier for people to grasp by stripping them to their essence. The very best analogies make things as simple as possible—but no simpler” (Pollack, 2014). Through analogous, combinatorial thinking, designers can generate new and stimulating solutions to current-day issues, and create a more adaptive architecture in the process.

I.3 Future trends

Since before the Industrial Revolution, companies have sought ways to streamline their operations through quicker production, fewer people, and faster assembly lines; although we now know that repetitive motion does not necessarily create healthy environments, quality products, and profitable companies. Thomas Petzinger argues that companies should stop mimicking machines and start relating more to living systems and human ecologies. By doing this, “[companies] are leading business back to its roots as a nature and fundamentally human institution” (Petzinger, 1999). That idea underpins the new human-centered economy emerging in our midst—one that the economist Jeremy Rifkin has called the “Third Industrial Revolution” (Rifkin, 2011). This is good news for the architectural profession. Industrial revolutions require the redesign of almost everything, and if the profession can cast aside some of its old practices and assumptions about what architecture entails and recognize the vast array of design opportunities that the new economy has created, the profession will see no end to the work it has to do.

Although Rifkin pays relatively little attention to architecture in his book, his argument has profound implications for the profession’s future: how we will plan cities, design buildings, practice architecture, and educate architects. The Third Industrial Revolution “will fundamentally change every aspect of the way we work and live,” Rifkin writes. Small-scale, crowd-funded fabrication will gradually replace large-scale, capital-intensive manufacturing; nimble, networked organizations will steadily prevail over big, hierarchical companies; and the global movement of digital files will increasingly supplant the global trade of goods. If the steam engine became the iconic technology of the First Industrial Revolution, and the assembly line that of the second, 3D printing may well become the icon of the third.

The field of architecture has experienced such massive economic disruptions before. The modern profession emerged during the First Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, as the mechanization of manual labor led to the need for new types of buildings, and as technology allowed us to build larger and taller. The profession as we still largely practice it today arose in the 20th century, as the mass production and consumption of the Second Industrial Revolution inspired the rise of specialized architectural firms able to mass-produce big buildings. It also gave birth to star architects (so called “starchitects”) able to create signature structures suitable for mass-media consumption.

Although the Second Industrial Revolution isn’t over yet, it has entered what Rifkin calls its “end game,” with an unsustainable dependence on fossil fuels and unsupportable levels of debt. Meanwhile, the Third Industrial Revolution has emerged at a staggering pace: consider how quickly social media has transformed the news business, online streaming has upended the music industry, and Google has become one of the most valuable companies in the world in just 15 years.

I.3.1 Wiki architecture

Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture’s design for the World Expo 2017 in Kazakhstan represents one of the first architectural explorations of Rifkin’s ideas. Comprising a globe-like national pavilion surrounded by streamlined structures for exhibits, meetings, and performances, the expo will have features that Rifkin sees as “pillars” of the new economy: renewable energy, hydrogen fuels, smart grids, and electric vehicles.

Expo 2017 will broadcast the idea of a Third Industrial Revolution to a global audience. But the real impact of this revolution on architecture will happen as we shift from an economy of mass production and consumption to an economy based on mass customization. That may not seem like a threat to architecture, as our field knows how to customize design to meet client needs. The challenge will come from learning how to mass customize architecture in an economy in which everyone may become a producer as well as a consumer of design.

Alastair Parvin, a U.K.-based designer, shows how this might happen: he and his team developed an open-source design of a small, extremely low-cost “WikiHouse” and demonstrated how ordinary people can download the file, cut out the parts on a computer-controlled machine, and erect the rectangular, gable-roofed structure themselves, without the need of tools or construction skills. If the 20th century “democratized consumption,” Parvin says, the 21st century will “democratize production,” with mass customization efforts like his.