![]()

1 Victims and Death and Illness in Context

OCCUPATIONAL HEALTH AND SAFETY IN CONTEXT

Read the corporate responsibility reports of most major national or multinational companies and the espoused values of our national regulator the Health and Safety Executive, and you might gain the impression of highly effective management with high ideals. They project an image of benign caring about others: they are there to protect vulnerable workers. But there is a dark side to the management of health and safety; it is a side that the companies and regulator will not even admit to themselves, let alone acknowledge in public. They produce their own victims. Accidents are unacceptable1,2,3,4,5 and, if one happens, someone must be punished. One such victim described his experience of being prosecuted by the HSE (Health and Safety Executive) and the characters involved:

There is at large a type of fanaticism which may or may not be political but is undoubtedly founded in an absolute conviction that the cause [H&S – author’s parentheses] is sacred. No one and nothing may stand in its path …

The State says that in the expert opinion of the enforcer you are guilty, so you must be. Prove us wrong, if you can, and we may let you get on with the rest of your life. But here’s the rub; the rules were written by the enforcer and he knows what he meant. But don’t worry – it’s all perfectly fair and above board because you will be tried before a jury of impartial people who haven’t a clue what’s going on. It’s all too technical for them, but they will be profoundly impressed by our imperious statutory credentials. Oh, and we can take our time (we don’t want to make any mistakes!) in getting you to court … Of course the special offer of 30% off the penalty is always open to those who choose to come quietly and admit publicly that the enforcer is right. There is the minor matter of a criminal record (you won’t be able to get household insurance, or travel to America, for a few years, amongst other nuisances, and your insurance might be a bit of a burden … and clients will run a mile … ).

The case involved a fatality during construction and the designer of the facility was taken to court over a technicality on the wording of a document he had produced. It took four years from the time of the fatality to the time of the trial. The case collapsed within a day. I interviewed this man several times over the period of a year. In the way he described the characters involved and how they behaved there is no doubt about the intensity of his experience. At first I was quizzical but the more I researched the more I realised that health and safety worldwide had lost its original moral purpose. What might have started out with high ideals had become a creeping malaise founded on inadequate, incomplete, misleading research fuelled by a naive belief in punitive enforcement, political correctness, vested interest, myopia, denial and dogma that few dare challenge.

Of course the health and safety community may claim that the example I use was an isolated case. They may claim that I am being sensationalist and subjective in order to make a point. They may even hint at paranoia by proxy. However, the anecdotal evidence, an examination of the HSE patterns of prosecution, and semantic analysis suggest that making examples of small organisations exists. Semantic analysis of documents from many organisations around the world shows an almost religious fervour for safety. As with any religion there are ranges of intensity and schisms. The evidence for this I shall explore in subsequent chapters. In the meantime, to put occupational health and safety in context, we must go back to a time when the concept of work as being a discrete separate part of existence did not exist.

Some 10,000–15,000 years ago hunter-gatherers lived in small nomadic autonomous groups. They left no written records but various anthropological studies have shown hunter-gatherers were multi-skilled and had a varied diet. It is a myth that they all had short lives. A meta-analysis (a study of studies) of longevity in hunter-gatherers by Gurven and Kaplan6 showed otherwise. This study also highlights one of the problems encountered in describing any indicator of quality of life (e.g. health and safety) – there are usually a variety of numerical ways of expressing what, at first sight, appears to be a simple concept. Life expectancy and longevity are no exception. They can be expressed as an average number of years from the time of birth, or the age at which the greatest numbers of deaths occur, or as frequency distribution or as a probability distribution, or at having reached a certain age what is the expected life remaining. Or the data is split into separate categories of infant mortality and adult mortality.

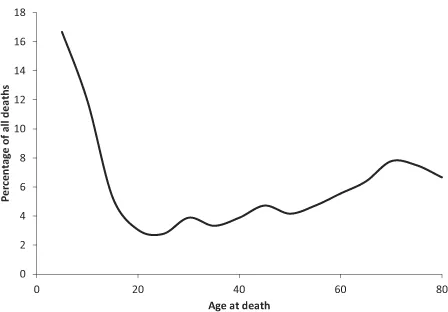

Expressed as a frequency distribution (Figure 1.1) it can be seen that, 10,000–15,000 years ago, hunter-gatherers had high infant mortality but, if they made it to adulthood, generally survived into their 70s.

During tens of millennia their life-style changed gradually from being nomadic hunter-gatherer to crop-grower and herder to the beginnings of urban dwelling. Man was settling down, living in communities and starting to specialise and starting to depend on others for food.

Figure 1.1 Mortality distribution prior to the agrarian revolution

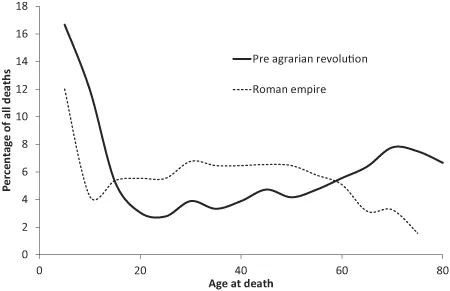

By Roman times, 2,000 years ago, there was an established society with an aristocratic ruling class and proletariat underclass. People were becoming progressively more specialist and beginning to live in cities. Roman peoples had higher infant mortality rates but, if they made it to adulthood, kept on dying (Figure 1.2). Both child mortality and adult mortality had worsened with advances in ‘civilization’.

Come forward in time to the 1800s and the industrial revolution. In the UK, society was stratified into an aristocracy, a growing middle class and the poor. Their work was split into different trades and professions, and most lived in cities. Food was dependent on a supply chain. With the passing of the Births and Deaths Registration Act in 1836 records started to be kept on the cause of death in England and Wales. An extract from the Registrar General’s Statistical Review of 18607 gives an inkling of what life was like during the industrial revolution.

Figure 1.2 Mortality distribution – hunter-gatherer man and Roman empire

Source: Graph derived from Gurven and Kaplan 2007, Frier’s Life Tables website

Out of the mass of detailed information a picture appears of high levels of infant mortality and early adult death mostly through diseases such as smallpox, measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria, croup and whooping cough. It was death and degradation on an industrial scale.

Out of this industrial hell also came the beginnings of care and concern for others. This appeared as social reform and public health investment. As with modern use of the Internet, mass communication played a part in raising public awareness of social issues. Newspapers and growing adult literacy provided the means by which writers such as Charles Dickens could describe the lot of the poor and powerless to the growing middle class and to those in power. Under the pen-name of Boz,8 Dickens eloquently portrayed the inequalities and degradation of Victorian city life. The period from 1819 through to the start of the First World War was characterised by growing numbers of Acts of Parliament such as the 1819 Health and Morals of Apprentices Act and the Factory Act, the 1833 Factory Act, the 1842 Mines Act and the 1847 Factory Act progressively reduced the number of hours worked and inhuman working conditions of women, children and men. In parallel with social reform came reform of water supply and effluent.

In 1854 the ‘most terrible outbreak of cholera which ever occurred in the United Kingdom’9 happened in the Soho area of London. At the time disease was thought to be caused by bad air: almost half the deaths in the period 1851–60 were attributed to ‘Miasmatic disease’. In an early example of the detective use of statistics, the physician John Snow was able to demonstrate that the source of the cholera outbreak was in fact drinking water that had been contaminated by sewage. The subsequent isolation of the source by removing the handle of the ‘Broad Street pump’ is credited as the beginning of epidemiology – the science of public health. The consequent realisation of the importance of clean drinking water was followed by water supply and sewer schemes throughout Victorian cities.

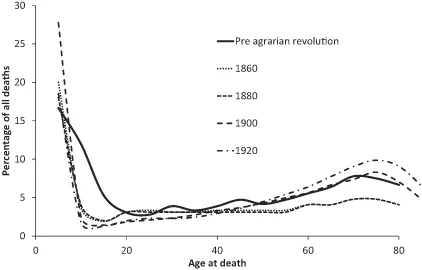

Examination of mortality distributions indicates a gradual improvement in the nation’s health (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Mortality distribution – hunter-gatherer man and late nineteenth/early twentieth centuries

Source: Graph derived from Gurven and Kaplan 2007, England and Wales registrars records

Eventually in the 1920s, life expectancy started to match that of hunter-gatherers some 10,000–15,000 years earlier. From then on it improved steadily. An acceleration in life expectancy followed another exercise in the detective use of statistics. In the 1950s and 1960s a team led by Richard Doll10 was able to demonstrate the link between smoking and a range of cancers and cardio vascular conditions. It was a disciplined and difficult enterprise that started ironically with ‘cohort studies’ of doctors who smoked. Gradually a picture of the effects of smoking emerged – so great was the public attachment to smoking that incontrovertible evidence was needed before the general public could be persuaded that it was deleterious to health. Other potential explanations (confounding variables) had to be eliminated before a sceptical public could be convinced. Such are the refinements of research into smoking that, using the technique of ‘odds ratios’ it is now possible to differentiate mortality rates between smokers of low and medium tar cigarettes.11

From the mid 1800s onwards there is evidence of growing interest in accidental death. One small entry in the 1860 Registrar General’s Statistical Review gives a clue of things to come. There is a list of deaths by ‘Accident or Negligence’

It lists ‘Fractures and contusions, Gunshot, Cut/stab, Burns and Scalds, Poison, Drowning and Suffocation’ as causes of death. The main items are fractures and contusions, burns and scalds and drowning. Notably fractures, contusions and drowning happened predominantly to men; burns and scalds are more or less equally split between both sexes. This data starts to give fragmentary clues about the comparative conditions in which both men and women lived or more specifically died. As time went on progressively more detail was included. By 1901 it was possible to differentiate between road transport and other forms of transport; by 1941 ‘falls’ became a separate category. Combining this data with census information to give frequency rates starts to give an idea of the scale of accidental death and how it changes with time (Figure 1.4).

Undoubtedly the biggest contributor to accidental death in the twentieth century was the motorcar. Death on the roads started to increase around 1905/6, took a break for World War 1, increased with a vengeance in the 1920s, peaked in the 1930s, took another break for World War 2, peaked again in the 1960s and has been gradually declining ever since. This decline notwithstanding, death on the roads remains the more or less equal first with falls as the greatest contributors to accidental death today.

The understanding of accidental injury and death in the workplace cannot be separated from understanding the nature of work itself. In Victorian times work was seen as a virtue. Hard work was considered a moral imperative; the inability to work or pay your way was seen as sinful. The poor who could not work ended up in the workhouse; the middle...