eBook - ePub

Socialism and Print Culture in America, 1897–1920

Jason D Martinek

This is a test

Condividi libro

- 224 pagine

- English

- ePUB (disponibile sull'app)

- Disponibile su iOS e Android

eBook - ePub

Socialism and Print Culture in America, 1897–1920

Jason D Martinek

Dettagli del libro

Anteprima del libro

Indice dei contenuti

Citazioni

Informazioni sul libro

For socialists at the turn of the last century, reading was a radical act. This interdisciplinary study looks at how American socialists used literacy in the struggle against capitalism.

Domande frequenti

Come faccio ad annullare l'abbonamento?

È semplicissimo: basta accedere alla sezione Account nelle Impostazioni e cliccare su "Annulla abbonamento". Dopo la cancellazione, l'abbonamento rimarrà attivo per il periodo rimanente già pagato. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

È possibile scaricare libri? Se sì, come?

Al momento è possibile scaricare tramite l'app tutti i nostri libri ePub mobile-friendly. Anche la maggior parte dei nostri PDF è scaricabile e stiamo lavorando per rendere disponibile quanto prima il download di tutti gli altri file. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui

Che differenza c'è tra i piani?

Entrambi i piani ti danno accesso illimitato alla libreria e a tutte le funzionalità di Perlego. Le uniche differenze sono il prezzo e il periodo di abbonamento: con il piano annuale risparmierai circa il 30% rispetto a 12 rate con quello mensile.

Cos'è Perlego?

Perlego è un servizio di abbonamento a testi accademici, che ti permette di accedere a un'intera libreria online a un prezzo inferiore rispetto a quello che pagheresti per acquistare un singolo libro al mese. Con oltre 1 milione di testi suddivisi in più di 1.000 categorie, troverai sicuramente ciò che fa per te! Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Perlego supporta la sintesi vocale?

Cerca l'icona Sintesi vocale nel prossimo libro che leggerai per verificare se è possibile riprodurre l'audio. Questo strumento permette di leggere il testo a voce alta, evidenziandolo man mano che la lettura procede. Puoi aumentare o diminuire la velocità della sintesi vocale, oppure sospendere la riproduzione. Per maggiori informazioni, clicca qui.

Socialism and Print Culture in America, 1897–1920 è disponibile online in formato PDF/ePub?

Sì, puoi accedere a Socialism and Print Culture in America, 1897–1920 di Jason D Martinek in formato PDF e/o ePub, così come ad altri libri molto apprezzati nelle sezioni relative a History e 20th Century History. Scopri oltre 1 milione di libri disponibili nel nostro catalogo.

Informazioni

1 ‘THE WORKINGMAN’S BIBLE’ AND THE MAKING OF AMERICAN SOCIALISM

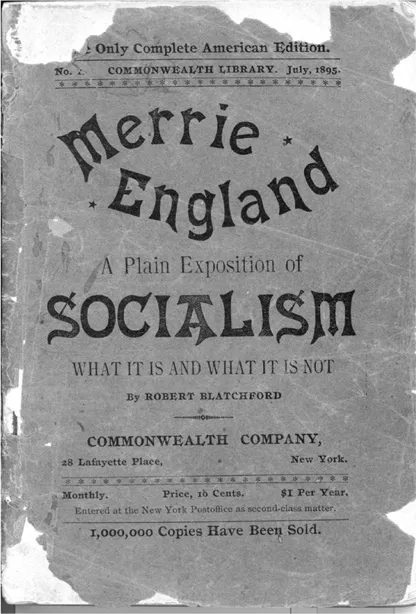

Age has made the booklet fragile. The red cover flakes away a little more at each handling. The newsprint has yellowed, hydrochloric acid slowly eating away the paper to nothingness. The book was never meant to last 100 years. It is about the size and shape of a dime novel – those penny dreadfuls that told exhilarating stories of murder, mayhem and adventure – but lacks the spectacular iconographic image of an especially climactic scene that no doubt tantalized prospective readers. Yet, despite its unostentatious cover, this one, too, works to draw in them. Especially eye-catching is the covers footer: ‘1,000,000 Copies Have Been Sold’. That was quite a boast, considering that publisher Houghton Mifflin ultimately sold only half that number of Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward.1 The book’s current decrepitude belies its significance. At one time, it, and hundreds of thousands like it, stoked the flames of discontent (see Figure 1.1). What was this book that purportedly trumped Looking Backward as a best-seller ? It was British writer Robert Blatchford’s Merrie England: A Plain Exposition of Socialism, whose first American edition appeared in 1895.

Appeal to Reason editor J. A. Wayland underscored the book’s significance to the turn-of-the-twentieth-century socialist movement when he dubbed it the ‘workingman’s bible’.2 Despite its vaunted place within the movement, the book has been forgotten. The Socialist Party’s leading historians – Howard H. Quint, Ira Kipnis, David A. Shannon and Paul Buhle – make no reference to it.3 Nor have American literary historians given Blatchford his just due. They have written about Henry George, Edward Bellamy, Henry Demarest Lloyd, Upton Sinclair and Jack London. Blatchford, by contrast, has received very little scholarly attention. Have American scholars ignored Blatchford simply because he was an Englishman?

Figure 1.1. Commonwealth Company edition of Meme England, 1895

Arguably, their tendency towards literary nationalism has obscured American culture s transnational dimension. Certainly, scholars like Daniel T. Rodgers have begun to counter this trend by showing how European thought influenced Progressive-era elites, but what remains largely unexamined is the transatlantic history of turn-of-the-twentieth-century working-class thought.4 In Blatchford’s own day, he existed outside the purview of the American literacy establishment. Middle-class readers devoured Looking Backward, Wealth Against Commonwealth and The Jungle, not Merrie England.

This chapter recovers the history of this forgotten best-seller of American socialism and shows how Eugene V. Debs and other leading socialists came to rely on Merrie England to forge a mass movement. I argue that the book’s immense popularity had a profound effect on socialists’ print culture of dissent, one that would shape its contours for the next decade. It led leaders to focus their efforts on converting the American public through reading, study and education. By over-emphasizing what the printed word could do, socialist leaders underestimated what it could not.

I.

1897 was a watershed year for American socialism. It marked the critical moment when a variety of socialist-tending reform currents converged under an organizational umbrella called the Social Democracy of America.5 An outgrowth of the American Railway Union, the Social Democracy was a major step towards socialism’s rise as a mass movement.

In June 1897, a greatly weakened American Railway Union (ARU) met for its convention at Uhlrich Hall in Chicago. Only 118 delegates – representing less than 4 per cent of its former members – attended this convention. Much had happened to the ARU between 1894 and 1897. It had become involved in a strike in Pullman, Illinois that culminated in a boycott of trains carrying Pullman palace cars. The boycott hampered railroad traffic nationwide and led to violent altercations in Chicago between workers and federal troops called in to protect railroad property and enforce a federal injunction against the union. Defying the injunction, the ARU’s directors were arrested and imprisoned; they included Debs, Sylvester Keliher, Louis W. Rogers, Roy M. Goodwin, James Hogan, William E. Burns and Martin J. Elliott. Overnight, Debs became a figure of national notoriety. Early after the strike’s start, the New York Times editorialized:

Eugene V. Debs, who within one week has sprung from obscurity to a position of the most absolute and potential power over all classes, millionaires, merchants, and mechanics, who by a mere nod controls and closes the business of the great railway systems as if these were but his toys, who commands a fairly well disciplined and blindly obedient army of about 1,600,000 desperate and determined men, who now controls all the traffic of 14 states, and coolly notifies the railway officials of all other States that he will attend to their cases unless they are very careful how they behave themselves, who has halted and sidetracked upward of 200 railway trains at various points of a territory far greater than all of Europe, who has crippled the commerce and manufactures of over 20 great cities, who has halted the United States mails in hundreds of places and defied the Federal government even to molest him, who spends $400 a day in telegraphic orders to his subordinates, who commands all of his great army of followers to cease all labor and give up all their daily wages, who is costing the great railways and cities a loss in trade and traffic of fully $10,000,000 each day, is yet a young man.6

This 200-plus word sentence could not have been any clearer about the potential and real threat that Debs posed to the nation. Single-handedly, he, at least according to this article, held the very fate of American capitalism in his hands. The very fact that Debs was able foment a national crisis at such a young age led the editorial writer to think about the apocalyptic future that certainly would come to pass if he was not stopped.

And yet, the ARU was in no shape to engender a revolution after Debs’s arrest. The ARU had amassed a huge debt defending its leaders in court, and this hampered any attempt to revitalize the organization. Moreover, railroad employers freely dismissed and blacklisted workers involved in the organization. The ARU of 1895 and 1896 was a mere shell of its former self. Debs and the other directors did not accept the organization’s decline without a fight. In fact, Debs spent most of his six-month prison term directing a union drive that he was sure would bring ‘more money than we have use for’ into the organization’s coffers by 1 January 1896. Despite this optimism, the reality was much bleaker, something that even Debs had to recognize when he was forced to tell the union organizers that they would have to be completely self-sufficient until the ‘financial condition of the order is such that we can again meet our obligations’.7

The failure of the ARU organizing drive gave forty-one-year-old Debs the opportunity to rethink his political convictions. He concluded that unions were not adequate to the task of emancipating workers from their oppression. This set Debs at odds with Samuel Gompers and other leaders of the American Federation of Labor who believed that trade unionism, ‘pure and simple’, was the best route to higher pay and better working conditions. Debs realized that change had to be political as well as economic since the federal government seemed to always come down on the side of capital in the labour wars of the late nineteenth century. While Debs came to this conclusion relatively quickly after federal troops crushed the Pullman Strike, he did not become a socialist for another two years.

Upon his release from prison, Debs became a staunch supporter of the People’s Party. A number of Socialist Party members would come to socialism through this same route. Debs accepted that Populism was a natural outgrowth of his belief that it was only through electoral politics that the American working classes could get fair treatment. Like other nineteenth-century labour republican thinkers, Debs believed that the ‘money power’ had corrupted the republic. Hence, only through political action could American liberty be redeemed:

It has been called ‘a weapon that executes a free man’s will as lightening does the will of God.’… There is nothing in our government it cannot make and unmake presidents and congresses and courts. It can abolish unjust judges, strip from them their robes and gowns and send them forth unclean as lepers to bear the mark of a murderer. It can sweep away trusts, syndicates, corporations, monopolies, and every other abnormal development of the money power designed to abridge the liberties of workingmen and enslave them by the degradation incident to poverty and enforced idleness, as cyclones scatter the leaves of the forest. The ballots can do all of this and more. It can give our civilization its crowning glory – the co-operative commonwealth.8

Debs spent much of 1896 on the road raising money to pay off the ARU’s debt by lecturing across the country on the ills that plagued American society and the necessity of voting the Populist ticket. Debs was such a good speaker on Populism’s behalf that there was talk about making him its candidate in the 1896 presidential election. If Debs had not sent a telegram to Henry Demarest Lloyd, the staunch anti-monopolist author of Wealth Against Commonwealth, saying, ‘Please do not permit use of name for nomination’, it is likely that he would have won the People’s Party nomination. After the Populists fused with the Democratic Party, Debs campaigned vigorously for William Jennings Bryan, despite the fact that Debs was not sure that free silver could solve the problems of late nineteenth-century America.9

Bryan lost the 1896 election to William McKinley, a pro-corporate candidate hand-picked by Ohio industrialist and Republican leader Marcus Hanna. More than anything else, the results of this election convinced Debs that the only way to make America a more equitable society was through socialism. In a letter to Henry Demarest Lloyd dated 12 December 1896, Debs gave the first indication that he was ready to add his voice to the socialist cause when he stated cryptically that ‘I desire to see you soon after New Year’s to advise with you in regard to the situation and the outlook and plans for the future. I have a matter of importance upon which I would like to have your views.’10 Debs sent a similar message to Victor Berger, a Milwaukee socialist who had visited Debs in Woodstock prison. According to Berger, Debs wrote, ‘I am much in favor of a conference after the first of the year. I shall want to see you and Mr. Lloyd and perhaps one or two others as a preliminary step. I have a proposition to make which I think will be favorably received.’11

But before Debs could have a conference with either of these men, he revealed his plans in the New Year...